Abstract

Purpose

Human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) have been applied in a variety of therapies recently. However, the role of MSCs in tumor progression remains largely elusive. Some studies demonstrated that MSCs can promote tumor growth, while others had opposite results. Therefore, the lack of evidence about the effect of MSCs on tumor cells impedes its further use.

Methods

In the current study, hMSCs from amniotic membrane (hAMSCs) and umbilical cord (hUCMSCs) were used to evaluate the effects of MSCs on tumor development in vitro and in vivo. Two different animal models based on subcutaneous xenograft bearing nude mice and a murine experimental metastatic model were established for in vivo study. Moreover, cytokines regulated by MSCs co-cultured with cancer cells SPC-A-1 were also analyzed by cytokine array.

Results

Our results indicated that hUCMSCs not only did not promote proliferation in cancer cells, but also inhibited migration. In addition, they inhibited tube formation in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs). Although hAMSCs also showed inhibitory effects on cancer cell motility, the proliferation of cancer cells was indeed enhanced. The in vivo data revealed that hUCMSCs did not promote tumor progression in lung adenocarcinoma and gastric carcinoma xenografts. Nevertheless, hAMSCs could do. The results from murine experimental metastatic model also demonstrated that neither hUCMSCs nor hAMSCs significantly enhanced the lung metastasis. The data from cytokine array showed that 11 inflammatory factors, 8 growth factors and 11 chemokines were remarkably secreted and changed.

Conclusions

In view of the data from in vitro and in vivo studies, the exploitation of hUCMSCs in new therapeutic strategies should be safe compared to hAMSCs under malignant conditions. Moreover, this is the first report to systematically elucidate the possible molecular mechanisms involved in UCMSC- and AMSC-affected tumor growth and metastasis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are a promising tool in cell therapies due to their multipotent, self-renewal, and immunomodulatory properties (Pittenger et al. 1999). MSCs can differentiate into multiple cell types such as osteoblasts, adipocytes, chondrocytes, myocytes, fibroblasts, epithelial cells and neurons. Therefore, MSCs show considerable therapeutic potential in genetic and acquired human diseases associated with the loss of specific tissues such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis, etc. (Arutyunyan et al. 2016; Uccelli et al. 2008). Several studies reported that MSCs could migrate to the sites of tumors. This migratory ability of MSCs might enable them to be utilized as the delivery vehicle for other anti-cancer drugs. However, the therapeutic application of MSCs in human malignancies could only be carried out after the validation of the effects of MSCs themselves (Serakinci et al. 2014). Currently, there are only limited studies investigating the properties of MSCs by animal models revealing inconsistent results. Some studies showed MSCs promoted tumor growth and metastasis, while others had opposite results. The controversial results and poorly understood mechanisms presented a serious obstacle to using MSCs clinically. Therefore, more studies about the effects of MSCs on tumor cells are needed to provide solid scientific evidences. Since 2006, our group has established stable MSC lines from human amniotic and umbilical cord mesenchymes (Hou et al. 2013; Meng et al. 2012). Among different MSCs, human amniotic mesenchymal stem cells (hAMSCs) and human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells (hUCMSCs) are the most potent and attractive stem cell sources for clinical use due to their easy, painless and safe (low risk of viral infection) collection procedures. Therefore, hAMSCs and hUCMSCs would be employed for our present study.

To further explore the role of MSCs on tumors, the effects of hAMSCs and hUCMSCs on lung adenocarcinoma cells, gastric carcinoma cells and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) were evaluated in vitro and in vivo. In addition, the possible molecular mechanisms involved in MSC-affected tumor growth and metastasis were also explored by the comprehensive cytokine secretion profile.

Materials and methods

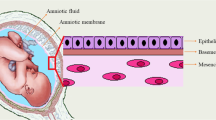

Isolation, culture and phenotyping of hAMSCs and hUCMSCs

Human umbilical cords were obtained from mothers who had given birth at Yan’an Hospital of Kunming Medical University. All subjects had obtained written informed consent before the study, which was approved by the ethics committee of Yan’an Hospital of Kunming Medical University. The protocol of the study conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1989 Declaration of Helsinki. The hAMSCs and hUCMSCs were isolated and amplified according to our previous study (Meng et al. 2012). The morphology of cells was observed and the photos were taken by a phase contrast microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The surface markers of hAMSCs and hUCMSCs including CD73, CD29, CD14, CD166, CD117, CD49, CD90, CD44, HLA-DR, CD45, CD34 were analyzed by flow cytometry (FACScalibur; Becton Dickinson) and CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson). The antibodies against the above surface markers were purchased from BD Biosciences, USA.

Multi-differentiation capabilities of hAMSCs and hUCMSCs

The pluripotency of hAMSCs and hUCMSCs were validated. Adipogenic, osteogenic and neurogenic differentiation experiments were performed as described previously (Meng et al. 2012). In brief, hAMSCs and hUCMSCs were cultured in Minimum Essential Medium Eagle—Alpha Modification (α-MEM) for 24 h. For adipogenic differentiation, the medium was then changed to Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 nmol/L dexamethasone, 10 mmol/L glycerophosphate and 0.2 mmol/L ascorbic acid 2-phosphate for 3 weeks and analyzed by Oil Red O staining. For osteogenic differentiation, α-MEM were changed to DMEM with low glucose (DMEM-LG) supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 nmol/L dexamethasone, 10 mmol/L-glycerophosphate, and 0.2 mmol/L l-ascorbic acid (Sigma-Aldrich) for about 3 weeks and assayed by von Kossa staining. The chondrogenic differentiation was conducted using the MSC go Chondrogenic XF™ Kit (Biological Industries, USA) for 3 weeks. The cells were then fixed with 10% formaldehyde for 24 h and embedded in paraffin. The blocks were sectioned at 4 µm thickness and stained with Alcian Blue Staining Kit (ScienCell, Carlsbad, CA Chondrogenesis Protocol: USA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The morphologies of cartilage lacuna and sulfated proteoglycan were identified under a light microscope (Primo Vert, Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Germany). For neural differentiation, the cells were cultured in α-MEM supplemented with 2% (v/v) FBS, 10 ng/mL basic fibroblast growth factor, 10 ng/mL platelet-derived growth factor, 0.1 µM dexamethasone, 0.5 µM linoleic acid and 50 mg/mL gentamicin sulfate (all from Sigma-Aldrich, USA) for 3 weeks and analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy after incubation with human monoclonal antibodies against neurofilament M (1:200; Millipore, Temecula, CA, USA).

Culturing of other cell lines

Human pulmonary adenocarcinoma cell line SPC-A-1 and gastric carcinoma cell line BGC-823 were purchased from Cell Bank of Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences, China. Human diploid cell line KMB-17, which originated from embryonic lung fibroblasts, was obtained from Institute of Medical Biology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Kunming, China.

SPC-A-1, BGC-823 and KMB-17 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Hyclone Laboratories) supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS, 100 IU/mL penicillin and 100 mg/mL streptomycin, and incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2, 95% humidified atmosphere.

Harvest of hAMSC- and hUCMSC-conditioned medium

The hAMSCs and hUCMSCs at passage 5 were cultured in 175 cm2 flask in 50 mL α-MEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 IU/mL penicillin and 100 mg/mL streptomycin until cells were approximately 80–90% confluent. At that time the medium was replaced with serum-free DMEM/F12 for 48 h. Subsequently, the conditioned medium was collected and centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 5 min. Then, it was filtered through a 0.22 µm syringe filter and conserved as AMSC-conditioned medium (AMSC-CM) and UCMSC-conditioned medium (UCMSC-CM) at -80 °C until use. The medium from KMB-17 was used as the control comparing with MSC-CM in our experiments. The procedure for collecting KMB-17-conditioned medium (KMB-CM) was the same as that of the MSC-CM.

Cell proliferation by CCK-8 Assay

SPC-A-1 and BGC-823 cells (both at 5 × 103 cells/well) were seeded in 96-well microplates for overnight. AMSC-CM or UCMSC-CM was added into cancer cells culture medium (RPMI 1640 medium with 10% FBS (v/v), 100 IU/mL penicillin and 100 mg/mL streptomycin) with concentrations of 20%, 40% and 60% respectively. After 72 h incubation, WST-8 (CCK-8, Dojindo Cell Counting Kit-8, Japan) was added to each well for the detection of cell proliferation according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The samples were firstly incubated at 37 °C for 1.5–2 h. The absorbance values at 450 nm were then measured by a microplate spectrophotometer (Varioskan Lux, Thermo Scientific, USA). Absorbance readings were blanked against the medium alone and the cell viability was expressed relative to vehicle control data.

Cell migration assay

The motility of SPC-A-1 and BGC-823 cells incubated with UCMSC-CM or AMSC-CM was assessed by the scratch wound assay. SPC-A-1 cells (5.0 × 105 cells/well) and BGC-823 cells (4.5 × 105 cells/well) were seeded in the Culture-Insert 2 Well in µ-Dish35mm, low (ibidi GmbH, Martinsried, Germany) and allowed for attachment for 24 h. Then, the Culture-Insert 2 Well was removed to create the cell-free gap. The medium was changed to UCMSC-CM or AMSC-CM for 12, 24, 36, or 48 h and each well was photographed at 40 × magnification under a light microscope. The percentages of open wound area were measured and calculated using the Image J 8.0 software. The motility was determined by the decrease in closed wound area as compared with control.

Matrigel invasion assay

The migration abilities of SPC-A-1 or BGC-823 cells were evaluated by the Matrigel invasion assay. Briefly, SPC-A-1 or BGC-823 cell suspension (4 × 104 cells in 100 µl UCMSC-CM or AMSC-CM) was added into each transwell filter upper chamber (8 µm pore size, Corning, USA). The filters were pre-coated with 200 µg/mL Matrigel in advance. 500 µL of complete cell culture medium (RPMI 1640 medium with 10% FBS v/v), serving as chemoattractant medium, were added to the lower chamber. The cells were migrated to the lower chamber after incubation for 24 h at 37 °C. The cells on the bottom surface of filter membrane were fixed with methanol and stained with crystal violet staining solution. Four areas of each stained filter were randomly photographed at 100x magnification under a light microscope. The migrated cancer cells were quantified by manual counting. Three independent experiments were performed with duplicate wells each. The changes in number of migrated cells were expressed as a percentage of control values.

Tube formation assay

To evaluate the effect of UCMSC-CM or AMSC-CM on formation of capillary tube-like structures, human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) were used in Matrigel-based assay. Briefly, a 24-well plate coated with Matrigel (0.5 mL/well, BD Biosciences, USA) was incubated at 37 °C for 0.5 h for gel solidification. HUVEC at 7.5 × 104 cells/well in 500 µl UCMSC-CM, AMSC-CM or DMEM/F12 (as control) media were added into separate wells and incubated for 8 h. UCMSC-CM and AMSC-CM was prepared from three independent experiments.

The enclosed networks of tubes were photographed under a light microscope. The total tube length of the tube structures in each photograph was analyzed by Image J 8.0 software.

Cytokine array

A multitude of cytokines secreted from MSCs are known to confer multiple functions in cancer development such as pro- and anti-inflammation, proliferation, differentiation, chemoattraction, etc. (Feng and Chen 2009; Park et al. 2009; Serakinci et al. 2014). To assess the mechanisms involved in the regulatory effects of MSCs on cancer cells, the changes of cytokine level in the co-cultured medium were analysed. Briefly, hAMSCs or hUCMSCs (1 × 105 cells/well) and SPC-A-1 (1 × 105 cells/well) were co-cultured in 6-well plates. After 24 h, the medium was changed to a serum-free one (DMEM/F12 : RPMI 1640 = 1:1) and incubated for another 48 h. Subsequently, the medium was collected and stored at − 80 °C. The AMSC-CM, UCMSC-CM and RPMI 1640 medium (without serum) from SPC-A-1 alone were also collected separately. The production of cytokines including inflammatory factors, growth factors and chemokines were measured by a commercially available kit Quantibody Human Cytokine Antibody Array 2000 (RayBiotech, Inc., Norcross, GA, USA) according to the instruction of the manufacturer. The level of cytokines from the samples was calculated according to corresponding standards.

In vivo evaluation of the cancer-promoting activity of MSCs

To evaluate the effect of hUCMSCs and hAMSCs on tumor formation and promotion in vivo, the murine subcutaneous xenograft cancer model was employed in the present study. The animal studies were reviewed and approved by the animal experimentation ethics committees of Yan’an Hospital of Kunming Medical University. Male BALB/c nude mice (6–8 wks of age) were provided by Hunan SJA Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd. The mice were bred and maintained in pathogen-free conditions. Numerous studies had previously reported that interleukin-6 (IL-6) was involved in the promotion of cancer growth (Tu et al. 2012). Therefore, one group of animals inoculated with cancer cells plus IL-6 was also included in our experiment. There were altogether 5 groups in the study: (1) SPC-A-1 or BGC-823 alone, (2) SPC-A-1 or BGC-823 with KMB-17, (3) SPC-A-1 or BGC-823 with hUCMSCs, (4) SPC-A-1 or BGC-823 with hAMSCs, (5) SPC-A-1 or BGC-823 with IL-6, with 6–7 mice allocated randomly into each group. Briefly, human cancer cells (SPC-A-1 or BGC-823, 1 × 106 cells/mouse) were injected subcutaneously into the back of the mice alone or mixed with hUCMSCs, hAMSCs, KMB-17 (all of three using 1 × 106 cells/mouse) or IL-6 (25 ng/mouse) on day 0. Tumor volume was measured every other day with a caliper and calculated using the formula (length × width2)/2 for 22 days. The mice were then euthanized and the tumors were dissected out. Tumor tissues were fixed in formaldehyde and processed for paraffin embedding. The paraffin-embedded tissue blocks were sectioned according to a previous study (Li et al. 2012), and were further used to assess the expression of Ki-67.

In another set of experiment, SPC-A-1 cells or BGC-823 cells (1 × 106 cells/mouse) in PBS were injected subcutaneously into the back of the mice. After 12 days, the mice were randomized into four groups with 5–6 animals in each group. Treatment with hUCMSC or hAMSC (5 × 105 cells/mouse), IL-6 (25 ng/mouse) or saline (as control) were conducted by i.v. injection through tail vein. Tumor volume was monitored every other day by caliper and calculated using the same formula with above. On day 22, the animals were killed and the tumors from the mice were collected for further analyses.

In vivo evaluation of the cancer metastatic activity of MSCs

To further access the effect of hUCMSCs and hAMSCs on cancer metastasis in vivo, the murine experimental metastatic model was performed as previously described with modification (Li et al. 2018). SPC-A-1 cells or BGC-823 cells in PBS (1 × 106 cells/mouse) were injected into male BALB/c nude mice via tail vein. After 24 h, the mice were randomized into four groups with 6–7 animals in each group. The hUCMSCs or hAMSCs (5 × 105 cells/mouse), IL-6 (25 ng/mouse) or saline (as control) were also injected via tail vein. On day 33, the mice were killed by cervical dislocation. The liver, lungs and tibia were dissected out and fixed with 10% formalin. The tibia was decalcified for 3 days. Then, all of the samples were processed for paraffin embedding and sectioned. The sections of lungs, liver or bone were stained with haematoxylin & eosin (H&E), and the tumor lesions in these organs were calculated according to previous studies (Li et al. 2017; Luo et al. 2013). The tumor lesions in lungs, defined as the tumor area, was calculated from the sections and expressed as an average tumor area per group in absolute units (µm2).

Statistical analysis

Values were expressed as mean + standard deviation (S.D.) for in vitro studies, and as mean + standard error of the mean (S.E.M.) for in vivo studies. One way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by post-hoc Dunnett’s multiple comparison test was used to compare the MSC (or IL-6) groups and the control group. The differences between the MSC-CM group and the control group were compared by unpaired t test. Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 5.0 software package (GraphPad Software Inc., CA, USA). Differences were considered to be statistically significant when P < 0.05.

Results

Characterization of morphology, MSC-specific surface markers and multi-differentiation capabilities of hUCMSCs and hAMSCs

The morphology of hUCMSC and hAMSC were basically similar, displaying consistent spindle shape with abundant cytoplasm and large nucleoli. When cells reached 70–80% confluence, they arranged in a whirlpool-like pattern (Fig. 1a, b). The specific surface receptor molecule expression was analyzed by flow cytometry. hUCMSCs and hAMSCs were positive for CD73, CD29, CD14, CD166, CD117, CD49, CD90, CD44, but expressions of HLA-DR, CD45 and CD34 were low. The data showed that the phenotypes of hUCMSCs and hAMSCs were basically indistinguishable from each other (Table 1). Representative photos of MSCs after differentiation are shown in Fig. 1c–j. Under different induction conditions, hUCMSCs and hAMSCs were able to differentiate into adipocytes (Fig. 1c, d), osteoblasts (Fig. 1e, f), chondrocytes (Fig. 1g, h) and neuron-like cells efficiently. The neuron-like cells showed positive expression of neurofilament M, which indicated that MSCs could differentiate into neural cells (Fig. 1i, j).

The characteristics of MSCs derived from human umbilical cord and amniotic mesenchymes. The morphology of hUCMSCs (a) and hAMSCs (b). c, d hUCMSCs and hAMSCs differentiated into adipocytes. The presence of triglycerides, characteristic of adipocytes, was revealed by staining with oil red O. e, f hUCMSCs and hAMSCs differentiated into osteoblasts. Calcium deposition was stained with Alizarin Red stain, indicating they were osteoblasts. g, h Chondrocytes differentiated from MSCs were evaluated by Alcian Blue Staining, which showed the characteristic morphology of cartilage lacuna and sulfated proteoglycan. i, j Neurogenic differentiation was detected by neurofilament M immunofluorescence staining

The effect of AMSC-CM and UCMSC-CM on proliferation of cancer cells SPC-A-1 and BGC-823

The effect of MSC-conditioned medium on the proliferative activity of malignant cells of different types of cancer including lung adenocarcinoma (SPC-A-1) and gastric carcinoma (BGC-823) was studied. The proliferation of cancer cells was not significantly changed after incubating with all concentration of UCMSC-CM, compared with the control (Fig. 2a, b). The proliferation of SPC-A-1 and BGC-823 was significantly increased after incubating with 40% (p < 0.01) and 60% (p < 0.001) AMSC-CM, respectively.

Evaluation of the effect of conditioned medium from MSC (MSC-CM) on the proliferation of cancer cells SPC-A-1 or BGC-823. MSC-CM was incubated for 24 h after seeding the cells in 96-well plates. Cell viability of SPC-A-1 (a, c) and BGC-823 (b, d) was assessed by the CCK8 assay after 72 h. Results were expressed as percentages of CCK8 absorbance with respect to the untreated control wells (mean ± SD of three independent experiments with five wells each). Differences between MSC-CM treated groups and control group were determined by Student’s unpaired t test. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 comparing MSC-CM treated groups with control

The effect of AMSC-CM and UCMSC-CM on migration of cancer cells SPC-A-1 and BGC-823

Migration and invasion of cancer cells is an essential process in cancer metastasis (Guan 2015; Valastyan and Weinberg 2011). The role of MSC-CM on the migration of cancer cells was assessed by the scratch wound assay and Matrigel invasion assay. As shown in Fig. 3a, c, d, incubation with UCMSC-CM or AMSC-CM resulted in decreased closed wound areas in SPC-A-1 cells compared with the respective controls, indicating that both UCMSC-CM and AMSC-CM (p < 0.01, p < 0.001) had significant inhibitory effects on migration of this type of cells. The motility of BGC-823 cells was also decreased by incubation with AMSC-CM (p < 0.05, p < 0.01). However, the motility of BGC-823 cells was not affected by incubation with UCMSC-CM (Fig. 3b, e, f). In addition, the results from Matrigel invasion assay showed that lots of cancer cells in the control wells, either SPC-A-1 or BGC-823, migrated from the upper to the lower chamber through the transwell membrane after 24 h incubation (Fig. 4a). In the presence of UCMSC-CM or AMSC-CM, the cell invasion of SPC-A-1significantly reduced by 23.14 ± 10.95% and 21.73 ± 12.00% respectively. Meanwhile, after exposure to AMSC-CM, cell invasion of BGC-823 also reduced by 15.74 ± 6.36%. However, the cell migration ability of BGC-823 incubated with UCMSC-CM was not changed (Fig. 4a, b).

The anti-migratory effect of MSC-CM on SPC-A-1 and BGC-823 cells. The representative photos showing human cancer cells SPC-A-1 or BGC-823 migrating across the scratch wound in the presence or absence of MSC-CM for 12, 24, 36 or 48 h incubation. The results are expressed as the percentage of closed wound area mean + SD of three independent experiments. Differences between MSC-CM treated groups and control group were determined by Student’s unpaired t test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 comparing MSC-CM treated groups with control

Effects of MSC-CM on migration of SPC-A-1 or BGC-823 cells in Boyden chambers. a Representative photomicrographs of the stained cells on the lower side of the membrane. b Quantification of migration of SPC-A-1 or BGC-823 cells. Results are expressed as the mean percentage of control (mean + SD of three independent experiments with two wells each). Difference between UCMSC-CM treated group (or AMSC-CM group) and control group with the same cell type was determined by Student’s unpaired t test, *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001 comparing treated groups with control

The effect of AMSC-CM and UCMSC-CM on tube formation of HUVEC

To investigate whether MSC-CM affected the ability of HUVEC to form capillary-like tubes, Matrigel angiogenesis assay was performed. The tube structures were visible in wells coated with BD Matrigel after 8 h (Fig. 5a). Figure 5b showed that treatment with UCMSC-CM inhibited tube formation of endothelial cells (p < 0.05). The effect of AMSC-CM on tube formation of HUVEC was not significant.

Effects of MSC-CM on capillary-like tube formation by HUVEC. a Representative photos showing the tube structures of HUVEC following 8 h MSC-CM incubation. b Quantification of tube formation in the presence or absence of UCMSC-CM and AMSC-CM in HUVEC are shown. Results are expressed as the mean percentage of control (mean + SD of three independent experiments). Differences between the MSC-CM treated and untreated control groups were determined by One way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by post-hoc Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, *p < 0.05 as compared to the control group

The influence of MSCs co-cultured with cancer cells on cytokines production

Since UCMSC-CM and AMSC-CM could significantly affect the proliferation and migration of SPC-A-1 cells, the release of cytokines from SPC-A-1 co-cultured with UC-MSCs or A-MSCs were simultaneously determined by cytokine antibody array that included 120 cytokines. Among them, 11 inflammatory factors (G-CSF, GM-CSF, ICAM-1, IL-1a, IL-1b, IL-1ra, IL-8, TIMP-2, IL-10, IL-16 and IL-6sR), 8 growth factors (BMP4, PDGF-AA, PDGF-BB, VEGF, EGFR, IGFBP2, IGFBP3 and bFGF) and 11 chemokines (CXCL6, CXCL16, IL-9, IL-18 BPa, LIF, Lymphotactin, MDC, MIF, MIP-3a, GRO and SDF-1a) were remarkably changed after co-culturing, which means these factors were involved in the regulation of MSC on SPC-A-1 cells (Table 2). By comparing to SPC-A-1 or MSC single cultures, the release of 24 cytokines were markedly increased by the co-culturing. Meanwhile, the release of six cytokines was declined after co-culturing. Amongst the down-regulated cytokines, the reduction of VEGF, PDGF and IL-6sR were the strongest. The levels of other cytokines such as bFGF, G-CSF, GM-CSF, ICAM-1, IL-18 BPa, IL-1b, IL-1ra, IL-16 etc., were elevated. The original blots of the cytokine arrays are shown in Supplementary Fig. 3 (standards not shown).

The effects of hAMSCs and hUCMSCs on tumor formation and promotion in vivo

To further evaluate the effects of MSC on tumor promotion in vivo, two animal models based on subcutaneous xenografts were employed in our study. Tumor xenografts were established successfully in nude mice after subcutaneous injection with both SPC-A-1 and BGC-823 cells. From the co-injection experiment, the tumor size of the SPC-A-1/hAMSCs group was significantly increased compared with SPC-A-1/KMB-17 or SPC-A-1 alone (p < 0.05, Fig. 6a). Meanwhile, the tumor size of BGC-823/hAMSCs group was also larger than those of the BGC-823-alone group (p < 0.05, Fig. 6b). These findings indicated that AMSCs were likely to be able to promote tumor growth, which was consistent with our in vitro result from CCK8 assay. On the other hand, no significant differences in tumor volume were observed in groups injected with SPC-A-1 or BGC-823 alone with the respective hUCMSCs co-injection groups, and SPC-A-1 or BGC-823 alone with the respective KMB-17 co-injection groups (Fig. 6a, b).

Effects of MSCs on nude mice model of xenograft tumor. a, b Mice were co-injected subcutaneously with SPC-A-1 or BGC-823 cancer cells and MSCs (hUCMSCs or hAMSCs). The cancer cells with KMB-17 was used as control in this animal model. *p < 0.05 SPC-A-1 + AMSC vs. SPC-A-1, #p < 0.05 SPC-A-1 + AMSC vs. SPC-A-1 + KMB-17, *p < 0.05 BGC-823 + AMSC vs. BGC-823 (one-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc Dunnett’s multiple comparison test). Each point represented a mean + S.E.M. of 6 or 7 tumors. c, d Mice were injected subcutaneously with SPC-A-1 or BGC-823 cancer cells. The following i.v. injection of MSCs (hUCMSCs or hAMSCs) commenced on day 12, n = 6–7. IL-6 was used as the positive control in this animal model. *p < 0.05 SPC-A-1 + IL-6 vs. SPC-A-1 (one-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc Dunnett’s multiple comparison test)

For another set of animal experiment, hUCMSCs or hAMSCs (or IL-6 as the positive control in this model) was intravenously injected into the mice through tail veins on the 12th day after tumor inoculation, when the tumors nodules were observed. As shown in Fig. 6c, the tumor of SPC-A-1 cells grew faster after treatment with IL-6 (p < 0.05), which was consistent with previous studies (Saglam et al. 2015). However, this effect was not observed in the co-injection experiment animal model (Fig. 6a, b). Notably, no significant difference in tumor volume was found among the SPC-A-1 (or BGC-823) with or without hUCMSCs (or hAMSCs) suggesting that MSCs did not promote tumor growth in this animal model (Fig. 6c, d).

To confirm the effect of MSC on tumor growth through cell proliferation, a Ki-67 immunostaining assay was performed on mice tumor sections. When compared with the other groups, the number of Ki-67 positive cells in tumor samples from SPC-A-1 or BGC-823 with hAMSCs was higher (Supplementary Fig. 1A&B). Moreover, in i.v. animal model, the cells with Ki-67 positive in the tumor regions from the IL-6-treated group (inoculated by SPC-A-1) were increased when compared with those from other groups, including SPC-A-1 alone, BGC-823 alone, and the respective hUCMSCs or hAMSCs co-injection groups (Supplementary Fig. 2A).

The effects of hAMSCs and hUCMSCs on cancer metastasis in vivo

No tumor metastatic lesions in other organs such as liver and lungs were observed in murine subcutaneous xenograft cancer model (Data not shown). To evaluate the ability of MSCs to induce tumor metastasis development, the murine experimental metastatic model was used. From our data, micro-metastasis of SPC-A-1 and BGC-823 in lungs were observed after H&E staining, as shown in red arrows in Fig. 7a, b. However, there were rarely obvious tumor metastatic lesions in the liver or bone, even in the murine experimental metastatic model. As shown in Fig. 7c, there were neither inhibitory nor induction effects of hAMSCs or hUCMSCs on tumor metastatic lesions in SPC-A-1 cancer model. At the same time, the lung metastasis in groups treated with IL-6 was slight increased, which was consistent with the tumor promotion effect of IL-6 in SPC-A-1 subcutaneous xenograft cancer model (Fig. 6c). The BGC-823 groups treated with hUCMSCs, hAMSCs or IL-6 did not show significant promotion in metastasis comparing with the control group (Fig. 7d).

Effects of MSCs on the murine experimental metastatic model. H & E staining was used to evaluate the lung metastasis of SPC-A-1 (a, c) or BGC-823 (b, d). a, b The representative photos of micro-metastasis in lungs with red arrows showing the tumor cells. c, d The histograms represented the tumor lesions in lungs as assessed by histological analysis, and expressed as an average tumor area per group in absolute units (µm2). Data shown in mean + SEM, n = 6–7 in each group

Discussion

MSCs from different tissues presented diverse effects on cancer progress (Akimoto et al. 2013). Due to the fact that MSCs showed different properties under malignant conditions, they need to be further investigated thoroughly and chosen carefully to balance the efficacy and safety for any particular cancer type. Although some studies showed that the MSCs from bone marrow promoted cancers such as osteosarcoma, colorectal tumor and gastric cancer (Tsai et al. 2011; Tu et al. 2012; Xue et al. 2015), the MSCs from adipose tissue or umbilical cord showed inhibitory effects on tumor cells from prostate tumor and glioma (Cavarretta et al. 2010; Ma et al. 2014). Obviously, the phenomenon was not absolute (Akimoto et al. 2013). The conflicting results regarding the pro- and anti-tumorigenic effects of MSCs on cancer may be due to the varying ratios of MSCs–cancer cells being administered, the different immune responses from immunocompromised or immunocompetent murine hosts, the diverse oncogenes, mutations, receptors, dysfunctioning of pathways on different kinds of cancer cell lines, and so on (Meng et al. 2018; O’Malley et al. 2016). In this study, MSCs from two different sources, umbilical cord and amniotic membrane, were simultaneously established to evaluate the effects on two different cancer cells SPC-A-1 and BGC-823, which were lung adenocarcinoma and gastric carcinoma respectively. The results demonstrated that MSCs from the umbilical cord was safer than those from the amniotic membrane, because UCMSCs not only did not promote the proliferation on the cancer cell lines and the ability of tube formation of human umbilical vein endothelial cells in vitro, but also inhibited the migration of cancer cells. Although AMSCs also inhibited the migration of cancer cells, the proliferation was indeed enhanced.

MSCs together with cancer cells (SPC-A-1 or BGC-823) were transplanted subcutaneously into BALB/c nude mice to observe the effects of MSCs on tumor growth in an in vivo model. In particular, the interactions of MSCs with other cell types, including tumor cells, immune cells, cancer-associated fibroblasts, endothelial cells of blood and lymphatic vessels, could modulate tumor development (Feng and Chen 2009). Recent studies showed that MSCs exerted their immunomodulatory effects, both immune-suppressive and promotive, in many pathological condition (Knaan-Shanzer 2014). Thus, the use of immunodeficient animal model might ignore the interaction among the cancer cells, host immune cells and MSCs. Xenograft models using immune competent animal models should be considered to resolve this problem. Each of the two animal models in the present study had its own advantages. The co-injection of MSCs with cancer cells into the mice best mimics the direct contact of the two types of cells. However, the intravenous injection of MSCs belonged to systematic infusion. MSCs appeared to migrate to tumor sites and played the roles through paracrine signals in the tissue microenvironment. This was closer to a clinical setting (Belmar-Lopez et al. 2013). Moreover, two different tumor xenografts from two cancer types, namely gastric carcinoma and lung adenocarcinoma, were employed to provide more representative information. Our in vivo results showed that AMSCs promoted tumor growth in co-injection with both SPC-A-1 and BGC-236 xenografts. This result was not observed in intravenous injection animal model. On the other hand, UCMSCs did not increase tumor size and Ki-67 expression in tumor sections in both animal models. No obvious side effects were observed after intravenous administration of hAMSCs and hUCMSCs in mice. Some studies demonstrated that IL-6 could promote tumor growth (Tu et al. 2012). Thus, IL-6 was used as the positive control in in vivo studies. However, the promotional effect of IL-6 was not obvious in co-injection model, which might be associated with the route of administration. For the intravenous injection model, IL-6 only showed promotional effects on SPC-A-1 xenografts, indicating its regulatory activity was cell-specific. Based on the current results, hUCMSCs did not have carcinogenic or cancer-promoting activities, which was more suitable for clinical use as comparing with hAMSCs. In addition, our previous study had evaluated the carcinogenic ability of UCMSCs in experimental animals and the normal chromosome karyotype of hUCMSCs (passages 7–23) (Meng et al. 2018), further supporting its potential use in clinical applications.

For assessment of the effects of MSCs on cancer metastasis, the murine experimental metastatic model was better than subcutaneous xenograft cancer model because there was rarely metastatic lesion in the latter. Metastasis is a complicated progress including tumor growth, angiogenesis, epithelial–mesenchymal transition, homing, and so on. The murine experimental metastatic model just mimicked the later progresses of cancer cell metastasis such as survival in the blood circulation, metastatic colonization and organ tropism (Quail and Joyce 2013). When cancer cells were injected via the tail vein, they first arrived at the lungs through the circulatory system. Therefore, the tumor metastatic lesions in our murine experimental metastatic model were mainly located in the lungs rather than liver or bones, which was a limitation of this model. Our results showed that MSCs did not significantly enhance the lung metastasis of SPC-A-1 or BGC-823, which was consistent with the in vitro data.

MSCs could secrete cytokines through paracrine pattern that participate in the regulation of different signaling pathways for cell proliferation, differentiation, migration, etc. (Knaan-Shanzer 2014) hAMSCs and hUCMSCs had been shown to inhibit the migration of cancer cells by regulating cytokine production in vitro. However, the lack of understanding of the mechanical and chemical interactions of the transplanted MSCs with the factors present in the cancer cells limited their use in cancer treatment. For the first time, our study conducted systematic analysis on cytokines from SPC-A-1 co-cultured with both UCMSCs and AMSCs. The results showed that BMP-4, PDGF-AA, PDGF-BB, VEGF and CXCL16 decreased after co-culturing, which might be associated with the anti-migration and anti-angiogenesis effects of MSCs (Deng et al. 2010; Feng and Chen 2009; Kim et al. 2015). However, there were still many cancer promoting factors being increased, such as EGFR, G-CSF, CXCL6, etc. (Nicholson et al. 2001; Verbeke et al. 2011). In general, administration with MSCs showed the ability of equilibrating the multiple factors in the microenvironment of cancer cells that led to tumor growth in vivo. Although the immunophenotypes of hUCMSCs and hAMSCs were basically similar (Table 1), the cytokines from the two MSCs, either co-cultured with cancer cells or not co-cultured, were greatly distinctive (Table 2). That may explain the difference in effects of hUCMSCs and hAMSCs on cancer cells. The role of MSCs in the pathogenesis and development of cancer is sophisticated and likely associated with the balance of competing inhibition and promotion forces. Due to the complex regulatory network, the detailed mechanisms need to be further studied based on our findings.

Taken together, the present study evaluated the effects of hUCMSCs and hAMSCs on cancer cell in vitro and in vivo. From our results, hUCMSCs did not affect the proliferation of cancer cells in both SPC-A-1 and BGC-823 cell lines, and inhibited the migration of SPC-A-1 as well as the tube formation of epithelial cells. Moreover, this was the first report that obtained the comprehensive cytokine secretion profile of human UCMSCs or AMSCs co-cultured with SPC-A-1 cancer cells, which provided the molecular basis for further studies. In vivo studies also found that hUCMSCs did not promote tumor development (tumor proliferation as well as lung metastasis). Therefore, the present findings provided scientific evidence on the safety and advantage of the use of hUCMSCs in pre-clinical setting.

References

Akimoto K, Kimura K, Nagano M, Takano S, To’a Salazar G, Yamashita T, Ohneda O (2013) Umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells inhibit, but adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells promote, glioblastoma multiforme proliferation. Stem Cells Dev 22:1370–1386. https://doi.org/10.1089/scd.2012.0486

Arutyunyan I, Elchaninov A, Makarov A, Fatkhudinov T (2016) Umbilical cord as prospective source for mesenchymal stem cell-based therapy. Stem Cells Int 2016:6901286. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/6901286

Belmar-Lopez C et al (2013) Tissue-derived mesenchymal stromal cells used as vehicles for anti-tumor therapy exert different in vivo effects on migration capacity and tumor growth. BMC Med 11:139. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-11-139

Cavarretta IT, Altanerova V, Matuskova M, Kucerova L, Culig Z, Altaner C (2010) Adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells expressing prodrug-converting enzyme inhibit human prostate tumor growth. Mol Ther 18:223–231. https://doi.org/10.1038/mt.2009.237

Deng L, Chen N, Li Y, Zheng H, Lei Q (2010) CXCR6/CXCL16 functions as a regulator in metastasis and progression of cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta 1806:42–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbcan.2010.01.004

Feng B, Chen L (2009) Review of mesenchymal stem cells and tumors: executioner or coconspirator? Cancer Biother Radiopharm 24:717–721. https://doi.org/10.1089/cbr.2009.0652

Guan X (2015) Cancer metastases: challenges and opportunities. Acta Pharm Sin B 5:402–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2015.07.005

Hou ZL et al (2013) Transplantation of umbilical cord and bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in a patient with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Cell Adh Migr 7:404–407. https://doi.org/10.4161/cam.26941

Kim JS, Kurie JM, Ahn YH (2015) BMP4 depletion by miR-200 inhibits tumorigenesis and metastasis of lung adenocarcinoma cells. Mol Cancer 14:173. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-015-0441-y

Knaan-Shanzer S (2014) Concise review: the immune status of mesenchymal stem cells and its relevance for therapeutic application. Stem Cells 32:603–608. https://doi.org/10.1002/stem.1568

Li L et al (2012) Eriocalyxin B induces apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells through caspase- and p53-dependent pathways. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 262:80–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.taap.2012.04.021

Li L et al (2017) The adjuvant value of Andrographis paniculata in metastatic esophageal cancer treatment - from preclinical perspectives. Sci Rep 7:854. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-00934-x

Li M et al (2018) Natural small molecule bigelovin suppresses orthotopic colorectal tumor growth and inhibits colorectal cancer metastasis via IL6/STAT3 pathway. Biochem Pharmacol 150:191–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2018.02.017

Luo KW et al (2013) Anti-tumor and anti-osteolysis effects of the metronomic use of zoledronic acid in primary and metastatic breast cancer mouse models. Cancer Lett 339:42–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2013.07.024

Ma S et al (2014) Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells inhibit C6 glioma growth via secretion of dickkopf-1 (DKK1). Mol Cell Biochem 385:277–286. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11010-013-1836-y

Meng MY et al (2012) Stemness gene expression profile analysis in human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 237:709–719. https://doi.org/10.1258/ebm.2012.011429

Meng MY et al (2018) Umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Am J Transl Res 10:212–223

Nicholson RI, Gee JM, Harper ME (2001) EGFR and cancer prognosis. Eur J Cancer 37(Suppl 4):S9–S15

O’Malley G, Heijltjes M, Houston AM, Rani S, Ritter T, Egan LJ, Ryan AE (2016) Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) and colorectal cancer: a troublesome twosome for the anti-tumour immune response? Oncotarget 7:60752–60774. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.11354

Park CW, Kim KS, Bae S, Son HK, Myung PK, Hong HJ, Kim H (2009) Cytokine secretion profiling of human mesenchymal stem cells by antibody array. Int J Stem Cells 2:59–68

Pittenger MF et al (1999) Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science 284:143–147

Quail DF, Joyce JA (2013) Microenvironmental regulation of tumor progression and metastasis. Nat Med 19:1423–1437. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.3394

Saglam O, Unal ZS, Subasi C, Ulukaya E, Karaoz E (2015) IL-6 originated from breast cancer tissue-derived mesenchymal stromal cells may contribute to carcinogenesis. Tumour Biol 36:5667–5677. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13277-015-3241-5

Serakinci N, Fahrioglu U, Christensen R (2014) Mesenchymal stem cells, cancer challenges and new directions. Eur J Cancer 50:1522–1530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2014.02.011

Tsai KS et al (2011) Mesenchymal stem cells promote formation of colorectal tumors in mice. Gastroenterology 141:1046–1056. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2011.05.045

Tu B, Du L, Fan QM, Tang Z, Tang TT (2012) STAT3 activation by IL-6 from mesenchymal stem cells promotes the proliferation and metastasis of osteosarcoma. Cancer Lett 325:80–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2012.06.006

Uccelli A, Moretta L, Pistoia V (2008) Mesenchymal stem cells in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol 8:726–736. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri2395

Valastyan S, Weinberg RA (2011) Tumor metastasis: molecular insights and evolving paradigms. Cell 147:275–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.024

Verbeke H et al (2011) Isotypic neutralizing antibodies against mouse GCP-2/CXCL6 inhibit melanoma growth and metastasis. Cancer Lett 302:54–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2010.12.013

Xue Z et al (2015) Mesenchymal stem cells promote epithelial to mesenchymal transition and metastasis in gastric cancer though paracrine cues and close physical contact. J Cell Biochem 116:618–627. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcb.25013

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Key Laboratory of Tumor Immunological Prevention and Treatment of Yunnan Province, 2017DG004; Nature Science Foundation of Yunnan Province, General Projects, 2017FB149.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

OpenAccess This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Meng, MY., Li, L., Wang, WJ. et al. Assessment of tumor promoting effects of amniotic and umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells in vitro and in vivo. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 145, 1133–1146 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-019-02859-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-019-02859-6