Abstract

Claudin-2 is a trans-membrane protein—component of tight junctions in epithelial cells. Elevated claudin-2 expression has been reported in colorectal cancer (CRC). The aim of this study was to investigate the expression patterns of claudin-2 in human CRC samples and analyze its association with clinical characteristics and treatment outcome. TMAs of primary tumors from two cohorts of metastatic CRC (mCRC) were used. Claudin-2 IHC staining was evaluated in a semi-quantitative manner in different regions and cell types. Claudin-2 expression was also analyzed by immunofluorescence in primary cultures of human CRC cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs). Initial analyses identified previously unrecognized expression patterns of claudin-2 in CAFs of human CRC. Claudin-2 expression in CAFs of the invasive margin was associated with shorter progression-free survival. Subgroup analyses demonstrated that the survival associations occurred among cases that received 5-FU+oxaliplatin combination treatment, but not in patients receiving 5-FU±irinotecan. The finding was validated by analyses of the independent cohort. In summary, previously unreported stromal expression of claudin-2 in CAFs of human CRC was detected together with significant association between high claudin-2 expression in CAFs and shorter survival in 5-FU+oxaliplatin-treated mCRC patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Up to 25% of colorectal cancer (CRC) patients have synchronous distant metastases at the time of diagnosis, and another 20–25% develop metachronous metastases [4, 29]. Surgical resection of the distant metastases, most often located to the liver, remains the only curative treatment leading to 5-year survival varying from 25 to 74% [7, 9]. KRAS and BRAF mutations are independent predictors for survival among patients who undergo liver metastases resection [12, 26]. Medical treatment of metastatic CRC (mCRC) includes combination chemotherapy with or without addition of targeted agents blocking EGFR-receptor signaling or angiogenesis. With the exception of RAS mutations, used as a marker to identify patients not benefiting from EGFR inhibitors, no biomarkers are clinically used for other pharmacological treatments of mCRC.

Tight junctions (TJs) are the most apical cell–cell adhesions in the epithelial cells. The claudin superfamily transmembrane proteins, including claudin-2, are important components of TJs. Under normal conditions, claudin-2 expression is associated with “leaky” epithelia of proximal tubule and in Bowman’s capsule of the nephron [14]. More recently, TJ proteins have been implied in “noncanonical” functions in epithelial and other cell types. Claudin-2 expression was reported, e.g., in osteoblasts [31], differentiated macrophages [28, 30], and endothelial cells of certain locations [5]. In normal gut, claudin-2 was detected in the intestinal crypts [22] and is overexpressed in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [6], CRC [13], and other tumor types [23].

Recently, claudin family proteins were also detected in cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) [11]. Functional significances of these findings remain to be elucidated. Mechanistic in vitro studies have indicated effects on differentiation and migration of claudins in stromal cells [10, 11].

CAFs are the most abundant cells in the solid tumor stroma. Emerging studies from model systems and from analyses of clinical samples indicate that CAFs constitute a diverse set of cells, composed of functionally and clinically relevant subsets, which may regulate tumor initiation, growth, progression, and response to treatment [8, 18]. Concerning the impact of CAFs on drug response, multiple mechanisms have been suggested which can broadly be divided into effects on drug exposure/delivery and effects on drug sensitivity [8, 17].

CAFs, and CAF-derived factors, can control drug delivery by affecting the interstitial fluid pressure (IFP). Reduction of IFP by enzymatic ablation of fibroblast-derived hyaluronan reexpanded the vasculature and improved drug delivery to the tumor site [21]. Similarly, usage of different PDGFR-β-antagonists, targeting CAFs, reduced IFP and improved transcapillary transport and tumoral uptake of chemotherapeutic drugs and radioimmunotherapeutic antibodies [2, 19]. Accordingly, PDGFR inhibitors improved therapeutic effects of cytotoxic drugs [20].

Based on these earlier findings, this study has explored the possibility that claudin-2 expression in CAFs is related to outcome in chemotherapy-treated patients with mCRC.

Materials and methods

A synopsis of the materials and methods is presented here. Full details are provided in the Supplementary Materials and Methods.

The SPCRC cohort—an unselected population diagnosed with nonresectable mCRC patients during 2003–2006 in three Scandinavian counties [24]—and the NORDIC-VII cohort from the randomized study investigated the effects of combining cetuximab with a regimen of bolus 5-flourouracil (5-FU)/folinic acid (FA) and oxaliplatin (FLOX) in first-line therapy of mCRC [27] were used.

Tissue microarrays (TMAs) were made from formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue blocks of primary tumor. For the current study, TMAs from 274 and 262 patients from the invasive margin and tumor center, respectively, from the SPCRC cohort and from 315 patients of the NORDIC-VII cohort were available for immunohistochemistry.

Immunohistochemical staining

Single- or double-staining procedures were applied for the TMA material with the antibodies to claudin-2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific Cat# 32-5600), CD68 (clone PG-M1; Dako, Inc., Denmark), and pan-cytokeratin antibody (clone AE1/AE3; Dako, Inc., Denmark). The abundance of the claudin-2 in tumor cells was evaluated as an integrated score, considering intensity of the expression and percentage of positive cells, using a four-graded scale (negative (0), weak (1), moderate (2), or strong (3)) and then dichotomized for survival analysis. Claudin-2-positive macrophage score was based on the quantity of marker-positive macrophages, irrespective of expression intensity. Claudin-2-positive CAF score was based on the abundance of dot-like expression (quantity of dots per area) irrespective of expression intensity. Evaluation of the ICH was performed by two pathologists: IH for SPCRC cohort (blinded to clinical and outcome data of SPCRC cohort) and AM for NORDIC-VII cohort (blinded to clinical and outcome data of NORDIC-VII).

In situ hybridization procedures

RNAscope® 2.5 HD Reagent Kit-RED (Advanced Cell Diagnostics, Hayward, CA) and a custom-designed RNAscope probe targeting 489–1408 of NM_020384.3 were used to detect CLDN2 transcript.

Fibroblast isolation from tumor tissue

The tissue samples were collected from five CRC patients and used to separate fibroblasts. The cells were subjected to immunofluorescence analysis with antibody to claudin-2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific Cat# 710221 or Thermo Fisher Scientific Cat# 32-5600), α-SMA (clone 1A4; Dako, Inc., Denmark, at dilution 1:300), or E-cadherin ((24E10) rabbit mAb, Cell Signaling Technology, at dilution 1:300).

Monocyte isolation and differentiation

Human monocytes were isolated from heparinized blood, obtained from healthy donors (The Republic Research & Production Centre for Transfusiology and Medical Biotechnologies, Minsk, Belarus), differentiated into M0-like cells by adhesion on plastic for 30 min, polarized to M2-like macrophages by incubation with 2 ng/ml M-CSF (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA) and/or 40 ng/ml IL-4 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) for 6 days and stained with antibodies to claudin-2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific Cat# 710221).

Statistical analyses

Cox proportional hazards model was used to estimate statistical significance and relative hazards in univariate and multivariate settings. Goodman–Kruskal gamma test was used for the analyses of marker expression in different locations. Mann–Whitney U test and ANOVA tests were used for the analyses of associations between marker expression and clinical characteristics. All statistical tests were two-sided, and p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Due to multiple tests applied for the survival analysis of claudin-2 expression in the SPSS cohort, the Bonferroni correction for the statistical significance was calculated and p value = 0.005 was considered as the threshold.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS V20 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Initial analyses were performed on tissue sections from human CRC tissue to characterize the patterns of claudin-2 expression. We observed claudin-2 in multiple cell types, including epithelial cells, endothelial cells, CAFs, and macrophages.

Claudin-2 is expressed in malignant and endothelial cells

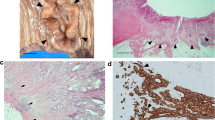

In malignant cells, a certain intra- and inter-case variability in the expression levels of claudin-2 was observed (Fig. 1a). Furthermore, different patterns of expression were detected including supra-nuclear, basal, and unpolarized expression (Supp. Fig. 1A).

Claudin-2 expression in human colorectal cancer tissue. a Representative image of tumor tissue without (upper image) and with high (lower image) claudin-2 expression in cancer cells. Note strong blue staining on pan-cytokeratin (red)-positive areas. b Expression of the claudin-2 in macrophages. Note dark-blue spots with irregular shape, frequently with a blank region in the centre (unstained nucleus). c Dot-like expression of the claudin-2 in cells with fibroblast-like morphology. d Expression of claudin-2, as determined by IF, in a fraction of cells within a primary CAF culture (passage 4). Note claudin-2 dot-like high-level expression in a cell marked “H” and low-level diffuse expression in a cell marked “L” (green) in fraction of CAFs. Red color used for the visualization of α-SMA

To investigate the potential impact on survival of claudin-2 expression pattern in malignant cells, an analysis with survival data from the SPCRC cohort was performed. Interesting, an unpolarized pattern was significantly associated with shorter overall survival (OS) (Supp Fig 2) with median 22.8 months for unpolarized pattern, and 38.1 and 38.4 months for supra-nuclear and basal patterns, respectively (p = 0.004). No associations with progression-free survival (PFS) were found (data not shown).

We also observed vascular expression of claudin-2, which was associated with endothelial cells (Supp. Fig. 1B). The observation is concordant with earlier reports [25]. A further analysis of vascular expression of claudin-2 was not performed in this study.

Claudin-2 is expressed in macrophages and CAFs

In agreement with previous studies, the appearance of claudin-2 in macrophages was also demonstrated by the presence of claudin-2/CD68 (pan-macrophage marker) double-positive cells in the stroma (see Fig. 1B and Supp. Fig. 1C). In noncancerous colonic mucosa, the claudin-2-positive macrophages represented a fraction of CD163+ (M2 macrophages) cells with localization restricted to the subepithelial region (see Supp Fig.2A). In the tumor stroma, we observed heterogeneous pattern of claudin-2 expression in macrophages with the presence of CD68+/cl2−, CD68+/cl2+ (see Fig. 1D2), CD163+/cl2− and CD163+/cl2+ cells (see Supp Fig.3B1 and C). Macrophages in peritumoral stroma, not adjacent to the tumor, were predominantly claudin-2-negative (see Supp Fig.3B2).

To extend these findings, we investigated the expression of claudin-2 in human blood monocyte-derived, polarized M2-class macrophages. M2-macrophage-like differentiation of human monocyte cells with M-CSF, IL-4, or M-CSF+IL-4 was reported elsewhere [32] (see “Materials and methods”). M0 cells and IL-4-alone or M-CSF-alone differentiated cells are characterized by low or absent expression of claudin-2 (see Supp Fig. 4A–C and 4E). However, when the combination of M-CSF and IL-4 was used for differentiation, the macrophages expressed high levels of claudin-2 (see Supp Fig. 4D, E).

Apart from the claudin-2-positive macrophages and vessels, additional dispersed dot-like claudin-2 expression was detected in other cells of the tumor stroma (Fig. 1C). These cells displayed an elongated spindle-shaped fibroblast-like morphology and were not juxtaposed to vessels, suggesting that they were CAFs. Additional tests were therefore done to validate the findings from the tissue-based analyses. Cultured primary fibroblasts, derived from surgically resected human CRC, were analyzed by IF. Two subsets of fibroblasts were observed: a subset with low level of cytoplasmic claudin-2 expression (Fig. 1d, “L” marked) and a subset with high level of dot-like claudin-2 expression (Fig. 1d, “H” marked). Both cell subsets were positive to α-SMA (Fig. 1d). CAF-expression of claudin-2 was confirmed in another experiment where cocultures of the primary fibroblasts and the CRC caco-2 cell line revealed claudin-2 expression in the E-cadherin-negative cells (Supp Fig. 5A.).

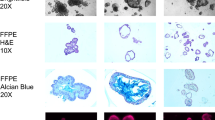

In order to validate specificity of the IHC staining of the claudin-2, we performed both IHC and in situ hybridization (ISH) on the sequential sections of FFPE sections. The mRNA targeting probes showed a signal pattern, which was similar to IHC expression pattern, with positivity in cancer cells, CAFs, macrophage-like cells, and nonmalignant colon epithelial cells (Supp Fig. 5B.).

Claudin-2 expression in cancer cells and fibroblasts at the invasive margin of the tumor is associated with KRAS mutation status

Following this initial profiling of claudin-2 expression in human CRC, we focused on the expression of claudin-2 in cancer cells and CAFs. As demonstrated by Goodman–Kruskal gamma test (Supp. Table 1), the expression of claudin-2 in CT and in IM was concordant based on analyses performed separately for cancer cells and CAFs (gamma test g = 0.63 and 0.37, respectively, both p < 0.001). When the correlation between the claudin-2 expression in cancer cells and in CAFs of the same location was analyzed, low concordance was observed in both CT and IM (g = 0.28, p < 0.001, and g = 0.24, p = 0.001, respectively).

To evaluate associations with clinicopathological characteristics, the semiquantitative data of claudin-2 expression was dichotomized into high and low values (see “Materials and methods”). High claudin-2 in malignant cells at the IM was more commonly seen in colon than in rectum tumors. Notably, high claudin-2 expression in malignant cells in the IM was also associated with KRAS, but not BRAF mutation status (Table 1.)

CAF-associated claudin-2 status predicts progression-free survival in the SPCRC cohort

No significant associations were detected between OS and claudin-2 expression in neither the malignant cells, nor the CAFs (data not shown). Furthermore, claudin-2 expression in the malignant cells was not associated with PFS (Supp. Fig. 6A). However, high expression of claudin-2 in CAFs in both CT and IM was significantly associated with shorter PFS (Fig. 2a) with median 8.8 and 7.4 months for low and high CAF-associated claudin-2 in CT, respectively (p = 0.002), and 10.1 and 7.4 months for low and high CAF-associated claudin-2 at IM, respectively (p = 0.005).

Associations between claudin-2 and progression-free survival (PFS). Kaplan–Meier graphs showing associations in the SPCRC cohort between PFS and claudin-2 expression in stromal cell/CAFs (a). Results from analyses of 5FU+oxaliplatin subgroup are shown in b. Results are shown separately for expression in central tumor (CT) (left panel) or invasive margin (IM) (right panel). HRs from Cox regression analyses, including confidence intervals, and p values are indicated for all analyses. Note, according to Bonferrony correction for the statistical significance, p value = 0.005 shall be considered as the threshold in the current illustration

The univariate analyses were expanded to multivariate analyses, including performance status, alkaline phosphatase, BRAF, and KRAS mutation status. In these analyses, only the CAF-associated expression of claudin-2 in the IM acted as an independent predictor for PFS (Table 2).

CAF-associated expression of claudin-2 at the invasive margin predicts response to oxaliplatin in the SPCRC cohorts

The survival analyses described above identified associations between claudin-2 status in CAFs with PFS, but not with OS. These findings prompted analyses exploring potential relationships between claudin-2 status and response to treatment. Additional PFS analyses were therefore performed to identify potential drug-specific associations between CAF-associated expression of claudin-2 and PFS. Depending on the treatment regimens used at the first-line treatment, three groups were identified: 5FU-alone group, 5FU+irinotecan, and 5FU+oxaliplatin group. The clinical characteristics of the patients from three treatment groups are shown in Supp. Table 2. Interestingly, the significant association between CAF claudin-2 and PFS, as determined by Cox regression analysis, was only detected in the 5FU+oxaliplatin group (p value = 0.027 and 0.001 for CT and IM CAF-associated claudin-2 expression, respectively, Fig. 2b and Supp Fig. 6B).

To expand these findings, multivariable analyses were performed on the treatment-defined subgroups (Table 3). High CAF-associated claudin-2 expression at IM then acted as a significant independent marker for shorter PFS in 5-FU+oxaliplatin group (p = 0.009). The expression in CT was not statistically significant (data not shown). Similar results were seen when 5-FU+oxaliplatin group was compared to merged 5FU-alone and 5FU+irinotecan group (data not shown).

These observations indicate that stromal expression of claudin-2 in the IM in primary CRC tissue predicts the response to oxaliplatin in first-line 5-FU-based treatment of mCRC.

Stromal claudin-2 expression predicts survival also in the NORDIC-VII cohort of mCRC

Additional analyses were performed to investigate if the findings could be reproduced in an independent patient cohort. For this purpose, a NORDIC-VII study derived TMA was analyzed with regard to CAF-associated expression of claudin-2. All patients in the NORDIC-VII trial received combined 5-FU plus oxaliplatin therapy (see “Materials and methods”).

In agreement with the findings from the SPCRC cohort, a statistically significant association between CAF-associated claudin-2 expression (but not cancer cell-associated claudin-2 expression) and PFS was detected (Fig. 3a, b).

This analysis provides independent evidence implying CAF-associated claudin-2 as a marker related to survival in mCRC treated with 5-FU+oxaliplatin. Notably, the treatment regimens of the NORDIC-VII population prevented analyses on oxaliplatin-specific survival associations CAF-associated claudin-2.

Claudin-2 expression is concordant in primary tumor and in metastases

The analyses above on survival of mCRC were based on claudin-2 expression in primary tumors. This prompted analyses where the marker expression in primary tumor and patient-matched metastases was compared. These analyses were restricted to the subset of cases where matched primary tumor and metastatic tissue was available. As shown in Supp. Table.3, claudin-2 expression showed good concordance between primary and metastatic tissue in both cancer cells and CAFs.

Discussion

Claudin-2 overexpression has been observed in CRC tissue. This is a first study to our knowledge, which reports a cell-type-specific analysis of the expression pattern of the protein in CRC.

We confirmed earlier described claudin-2 expression in cancer cells and described three distinct expression patterns. The intracellular localization patterns of the claudin-2 were not associated with the abundance of the protein. Notably, a survival association was detected for the unpolarized pattern. Possibly, this finding could be related to cell polarization/differentiation status of cells, and thus not causally linked to claudin-2-related biology.

The key findings of the present study are that claudin-2 is expressed in CAFs in primary tumor tissue of mCRC in a manner which is linked to KRAS mutation status and progression-free survival. Notably, the progression-free-survival association is restricted to the subset of patients treated with 5-FU+oxaliplatin.

CAF expression of claudin-2 in CRC has not been previously reported. However, other TJ proteins such as occludin and claudin-11 have been detected in CAFs of other tumor types [11]. Preliminary mechanistic studies have linked TJ protein expression in CAFs to increased migratory activity [11]. Further mechanistic studies on how claudin-2 expression affects CRC CAF phenotypes are warranted by the findings of the present study.

We report an association between oncogenic KRAS status and claudin-2 expression in malignant cells. Earlier studies have implied TGF-beta as an inducer of some TJ proteins in CAFs and epithelial cells [11, 15]. On another hand, some studies indicate that claudin-2 expression upregulates TGF-beta production in colonic epithelial cells and induce immune suppression [1]. Future studies should thus explore if the associations between oncogenic RAS and CAF-associated claudin-2 involves RAS-induced TGF-beta production.

The treatment-specific associations between claudin-2 and outcome are intriguing and merit further investigation. Experimental studies should explore if claudin-2 status of fibroblasts can regulate 5FU/oxaliplatin-sensitivity of cocultured CRC cells. Animal studies can also be performed where 5FU/oxaliplatin-sensitivity can be analyzed in tumor xenografts formed after coinjection of CRC cells and CAFs of defined claudin-2 status.

CAF subsets may have different impact on drug delivery by affecting the IFP. It has been shown before that increased fluid flow, caused by the differences between IFP in tumor and peritumoral regions can affect delivery of molecules in a manner that is related to their molecular weight [3, 16]. Molecular weights of both fluorouracil and oxaliplatin are comparable (0.130 and 0.397 kDa, respectively). Possibly, differential associations with macromolecules could affect delivery of the drugs and the IFP dependency. Future experimental studies on this topic are warranted.

Future studies should also consider the possibility that the oxaliplatin-treated cases represent a subgroup of CRC where claudin-2 expression is related to intrinsic tumor aggressiveness. In the SPCRC cohort, the oxaliplatin-receiving group differs from the fluoropyrimidine-alone-treated group by being younger and by displaying better WHO PS (Supp. Table 2). The CAF claudin-2 survival association remained in analyses performed in age- or PS-defined oxaliplatin-treated subgroups (data not shown) and in multivariate Cox regression models. Age or WHO PS is thus not explaining the treatment-specific CAF claudin-2 association with survival. The association seen in the Nordic VII study, where all patients received oxaliplatin, further strengthens our conclusion that claudin-2 expression is related to oxaliplatin treatment response.

Findings of the present study provide additional support for the notion that CAFs are clinically relevant regulators of drug sensitivity. As such, findings should stimulate to continued explorations of CAFs as sources of mechanistically relevant prognostic and response-predictive biomarkers.

References

Ahmad R, Chaturvedi R, Olivares-Villagomez D, Habib T, Asim M, Shivesh P, Polk DB, Wilson KT, Washington MK, Van Kaer L, Dhawan P, Singh AB (2014) Targeted colonic claudin-2 expression renders resistance to epithelial injury, induces immune suppression, and protects from colitis. Mucosal Immunol 7:1340–1353. https://doi.org/10.1038/mi.2014.21

Baranowska-Kortylewicz J, Abe M, Pietras K, Kortylewicz ZP, Kurizaki T, Nearman J, Paulsson J, Mosley RL, Enke CA, Ostman A (2005) Effect of platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta inhibition with STI571 on radioimmunotherapy. Cancer Res 65:7824–7831. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3991

Baxter LT, Jain RK (1989) Transport of fluid and macromolecules in tumors. I. Role of interstitial pressure and convection. Microvasc Res 37:77–104

Elferink MA, de Jong KP, Klaase JM, Siemerink EJ, de Wilt JH (2015) Metachronous metastases from colorectal cancer: a population-based study in North-East Netherlands. Int J Color Dis 30:205–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-014-2085-6

Garcia-Godinez A, Contreras RG, Gonzalez-Del-Pliego M, Aguirre-Benitez E, Acuna-Macias I, de la Vega MT, Martin-Tapia D, Solano-Agama C, Mendoza-Garrido ME (2014) Anterior and intermediate pituitary tissues express claudin 4 in follicle stellate cells and claudins 2 and 5 in endothelial cells. Cell Tissue Res 357:309–321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00441-014-1827-7

Gunzel D, Fromm M (2012) Claudins and other tight junction proteins. Comprehensive Physiology 2:1819–1852. https://doi.org/10.1002/cphy.c110045

House MG, Ito H, Gönen M, Fong Y, Allen PJ, DeMatteo RP, Brennan MF, Blumgart LH, Jarnagin WR, D'Angelica MI (2010) Survival after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: trends in outcomes for 1,600 patients during two decades at a single institution. J Am Coll Surg 210(744–752):752–745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.12.040

Kalluri R (2016) The biology and function of fibroblasts in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 16:582–598. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc.2016.73

Kanas GP, Taylor A, Primrose JN, Langeberg WJ, Kelsh MA, Mowat FS, Alexander DD, Choti MA, Poston G (2012) Survival after liver resection in metastatic colorectal cancer: review and meta-analysis of prognostic factors. Clinical Epidemiology 4:283–301. https://doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S34285

Karagiannis GS, Poutahidis T, Erdman SE, Kirsch R, Riddell RH, Diamandis EP (2012) Cancer-associated fibroblasts drive the progression of metastasis through both paracrine and mechanical pressure on cancer tissue. Mol Cancer Res 10:1403–1418. https://doi.org/10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-12-0307

Karagiannis GS, Schaeffer DF, Cho CK, Musrap N, Saraon P, Batruch I, Grin A, Mitrovic B, Kirsch R, Riddell RH, Diamandis EP (2014) Collective migration of cancer-associated fibroblasts is enhanced by overexpression of tight junction-associated proteins claudin-11 and occludin. Mol Oncol 8:178–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molonc.2013.10.008

Karagkounis G, Torbenson MS, Daniel HD, Azad NS, Diaz LA Jr, Donehower RC, Hirose K, Ahuja N, Pawlik TM, Choti MA (2013) Incidence and prognostic impact of KRAS and BRAF mutation in patients undergoing liver surgery for colorectal metastases. Cancer 119:4137–4144. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28347

Kinugasa T, Huo Q, Higashi D, Shibaguchi H, Kuroki M, Tanaka T, Futami K, Yamashita Y, Hachimine K, Maekawa S, Nabeshima K, Iwasaki H, Kuroki M (2007) Selective up-regulation of claudin-1 and claudin-2 in colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res 27:3729–3734

Kiuchi-Saishin Y, Gotoh S, Furuse M, Takasuga A, Tano Y, Tsukita S (2002) Differential expression patterns of claudins, tight junction membrane proteins, in mouse nephron segments. J Am Soc Nephrol 13:875–886

Kojima T, Takano K, Yamamoto T, Murata M, Son S, Imamura M, Yamaguchi H, Osanai M, Chiba H, Himi T, Sawada N (2008) Transforming growth factor-beta induces epithelial to mesenchymal transition by down-regulation of claudin-1 expression and the fence function in adult rat hepatocytes. Liver Int : Official J Int Assoc Study Liver 28:534–545. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1478-3231.2007.01631.x

Munson JM, Shieh AC (2014) Interstitial fluid flow in cancer: implications for disease progression and treatment. Cancer Manag Res 6:317–328. https://doi.org/10.2147/CMAR.S65444

Ostman A (2012) The tumor microenvironment controls drug sensitivity. Nat Med 18:1332–1334. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.2938

Ostman A, Augsten M (2009) Cancer-associated fibroblasts and tumor growth--bystanders turning into key players. Curr Opin Genet Dev 19:67–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gde.2009.01.003

Pietras K, Ostman A, Sjoquist M, Buchdunger E, Reed RK, Heldin CH, Rubin K (2001) Inhibition of platelet-derived growth factor receptors reduces interstitial hypertension and increases transcapillary transport in tumors. Cancer Res 61:2929–2934

Pietras K, Rubin K, Sjoblom T, Buchdunger E, Sjoquist M, Heldin CH, Ostman A (2002) Inhibition of PDGF receptor signaling in tumor stroma enhances antitumor effect of chemotherapy. Cancer Res 62:5476–5484

Provenzano PP, Cuevas C, Chang AE, Goel VK, Von Hoff DD, Hingorani SR (2012) Enzymatic targeting of the stroma ablates physical barriers to treatment of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell 21:418–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2012.01.007

Rahner C, Mitic LL, Anderson JM (2001) Heterogeneity in expression and subcellular localization of claudins 2, 3, 4, and 5 in the rat liver, pancreas, and gut. Gastroenterology 120:411–422

Soini Y (2005) Expression of claudins 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 7 in various types of tumours. Histopathology 46:551–560. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02127.x

Sorbye H, Dragomir A, Sundstrom M, Pfeiffer P, Thunberg U, Bergfors M, Aasebo K, Eide GE, Ponten F, Qvortrup C, Glimelius B (2015) High BRAF mutation frequency and marked survival differences in subgroups according to KRAS/BRAF mutation status and tumor tissue availability in a prospective population-based metastatic colorectal cancer cohort. PLoS One 10:e0131046. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0131046

Tan X, Li D, Wang X, Zeng Y, Yan Y, Yang L (2014) Claudin-2 downregulation by KSHV infection is involved in the regulation of endothelial barrier function. J Cutan Pathol 41:630–639. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.12332

Teng HW, Huang YC, Lin JK, Chen WS, Lin TC, Jiang JK, Yen CC, Li AF, Wang HW, Chang SC, Lan YT, Lin CC, Wang HS, Yang SH (2012) BRAF mutation is a prognostic biomarker for colorectal liver metastasectomy. J Surg Oncol 106:123–129. https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.23063

Tveit KM, Guren T, Glimelius B, Pfeiffer P, Sorbye H, Pyrhonen S, Sigurdsson F, Kure E, Ikdahl T, Skovlund E, Fokstuen T, Hansen F, Hofsli E, Birkemeyer E, Johnsson A, Starkhammar H, Yilmaz MK, Keldsen N, Erdal AB, Dajani O, Dahl O, Christoffersen T (2012) Phase III trial of cetuximab with continuous or intermittent fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin (Nordic FLOX) versus FLOX alone in first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: the NORDIC-VII study. J Clin Oncol 30:1755–1762. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.38.0915

Van den Bossche J, Laoui D, Morias Y, Movahedi K, Raes G, De Baetselier P, Van Ginderachter JA (2012) Claudin-1, claudin-2 and claudin-11 genes differentially associate with distinct types of anti-inflammatory macrophages in vitro and with parasite- and tumour-elicited macrophages in vivo. Scand J Immunol 75:588–598. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3083.2012.02689.x

van der Geest LG, Lam-Boer J, Koopman M, Verhoef C, Elferink MA, de Wilt JH (2015) Nationwide trends in incidence, treatment and survival of colorectal cancer patients with synchronous metastases. Clinical Experimental Metastasis 32:457–465. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10585-015-9719-0

Whitcomb DC, LaRusch J, Krasinskas AM, Klei L, Smith JP, Brand RE, Neoptolemos JP, Lerch MM, Tector M, Sandhu BS, Guda NM, Orlichenko L, Alzheimer's Disease Genetics C, Alkaade S, Amann ST, Anderson MA, Baillie J, Banks PA, Conwell D, Cote GA, Cotton PB, DiSario J, Farrer LA, Forsmark CE, Johnstone M, Gardner TB, Gelrud A, Greenhalf W, Haines JL, Hartman DJ, Hawes RA, Lawrence C, Lewis M, Mayerle J, Mayeux R, Melhem NM, Money ME, Muniraj T, Papachristou GI, Pericak-Vance MA, Romagnuolo J, Schellenberg GD, Sherman S, Simon P, Singh VP, Slivka A, Stolz D, Sutton R, Weiss FU, Wilcox CM, Zarnescu NO, Wisniewski SR, O'Connell MR, Kienholz ML, Roeder K, Barmada MM, Yadav D, Devlin B (2012) Common genetic variants in the CLDN2 and PRSS1-PRSS2 loci alter risk for alcohol-related and sporadic pancreatitis. Nature Genetics 44:1349–1354. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2466

Wongdee K, Pandaranandaka J, Teerapornpuntakit J, Tudpor K, Thongbunchoo J, Thongon N, Jantarajit W, Krishnamra N, Charoenphandhu N (2008) Osteoblasts express claudins and tight junction-associated proteins. Histochem Cell Biol 130:79–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00418-008-0419-6

Zhang H, Xue C, Shah R, Bermingham K, Hinkle CC, Li W, Rodrigues A, Tabita-Martinez J, Millar JS, Cuchel M, Pashos EE, Liu Y, Yan R, Yang W, Gosai SJ, VanDorn D, Chou ST, Gregory BD, Morrisey EE, Li M, Rader DJ, Reilly MP (2015) Functional analysis and transcriptomic profiling of iPSC-derived macrophages and their application in modeling Mendelian disease. Circ Res 117:17–28. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.305860

Acknowledgements

Tommy Linné, Karolinska Institutet, and members of the AÖ group with special thanks to Mercedes Herrera Torres are acknowledged for providing support and constructive criticism during the studies.

Human Protein Atlas Group is acknowledged for scanning and TMA construction.

Funding

AÖ receives support from Swedish Cancer Society (Cancerfonden), Radiumhemmets forskningsfonder and the STARGET Linné-grant from Swedish Research Council. AM was also supported by a grant from Svenska Institutet. The collection of the patient materials and TMA production were also supported by the Swedish Cancer Society. The NORDIC-VII study was supported by Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany), Sanofi (Oslo, Norway), the Norwegian Cancer Society, and the Swedish Cancer Society.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All coauthors contributed to conception or design of the work or the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data for the work; drafting the work or revising it; final approval of the version to be published; and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Sample collection and its usage for scientific needs were approved by the local ethical committee (The Republic Research & Production Centre for Transfusiology and Medical Biotechnologies, Minsk, Belarus). For human cancer tissue samples, TMA preparation and usage for scientific purposes was approved. Ethical approval IDs are DNR 2005:M-076, VF 20050053, and 129-05045.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 24361 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Mezheyeuski, A., Strell, C., Hrynchyk, I. et al. Treatment-related survival associations of claudin-2 expression in fibroblasts of colorectal cancer. Virchows Arch 472, 395–405 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-017-2263-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-017-2263-3