Abstract

Purpose

Kono-S anastomosis, an antimesenteric, functional, end-to-end handsewn anastomosis, was introduced in 2011. The aim of this meta-analysis is to evaluate the safety and effectivity of the Kono-S technique.

Methods

A comprehensive search of MEDLINE (PubMed), Embase (Elsevier), Scopus (Elsevier), and Cochrane Central (Ovid) from inception to August 24th, 2023, was conducted. Studies reporting outcomes of adults with Crohn’s disease undergoing ileocolic resection with subsequent Kono-S anastomosis were included. PRISMA and Cochrane guidelines were used to screen, extract and synthesize data. Primary outcomes assessed were endoscopic, surgical and clinical recurrence rates, as well as complication rates. Data were pooled using random-effects models, and heterogeneity was assessed with I² statistics. ROBINS-I and ROB2 tools were used for quality assessment.

Results

12 studies involving 820 patients met the eligibility criteria. A pooled mean follow-up time of 22.8 months (95% CI: 15.8, 29.9; I2 = 99.8%) was completed in 98.3% of patients. Pooled endoscopic recurrence was reported in 24.1% of patients (95% CI: 9.4, 49.3; I2 = 93.43%), pooled surgical recurrence in 3.9% of patients (95% CI: 2.2, 6.9; I2 = 25.97%), and pooled clinical recurrence in 26.8% of patients (95% CI: 14, 45.1; I2 = 84.87%). The pooled complication rate was 33.7%. The most common complications were infection (11.5%) and ileus (10.9%). Pooled anastomosis leakage rate was 2.9%.

Conclusions

Despite limited and heterogenous data, patients undergoing Kono-S anastomosis had low rates of surgical recurrence and anastomotic leakage with moderate rates of endoscopic recurrence, clinical recurrence and complications rate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a relapsing inflammatory condition which can affect any portion of the digestive tract, leading to long term transmural inflammation with structural bowel damage and complications such as abscesses, fistulas, and strictures [1]. In addition to the economic burden CD imposes on healthcare, with annual costs reaching €30 billion in the United States and Europe, the physical, emotional, and social consequences of the disease have shown to negatively affect patients’ quality of life [2].

When Crohn and his colleagues first described regional ileitis in 1932, surgical resection was the only effective treatment available [3, 4], but the development of safe and efficacious immunosuppressors and biological therapies over the past three decades has widened the range of medical therapies [5]. Despite those advancements in medical therapy, the cumulative risk of surgery 10 years after diagnosis of Crohn’s disease remains 46.6% [6]. However, studies have shown that endoscopic postoperative recurrence can be detected in up to 70% of CD patients as early as 1 year after intestinal resection [7] and rates of re-operation reach 20–44% at 10 years and 46–55% at 20 years [8]. From a surgical perspective, the question arises of whether alteration in the surgical method could result in decreased reoperative rates. Several theories have proposed that factors including the anastomotic technique, mesenteric involvement, lumen size, anastomotic orientation (end-to-end versus side-to-side), anastomotic method (handsewn versus stapled) and rate of anastomotic insufficiency, plays a pivotal role in postoperative disease recurrence [9]. However, there is currently no consensus on the superiority of a specific anastomotic technique [10].

Kono-S anastomosis, an antimesenteric, functional, end-to-end handsewn anastomosis, was introduced in 2011 to reduce anastomotic leakage and postoperative recurrence of CD [11]. The surgical technique consists of transecting the intestine using a linear staple cutter such that the mesenteric side is in the center of the stump, at a 90° angle to the mesentery. Reinforcing and connecting both ends of the stump creates a supporting column and helps maintain the orientation and large lumen diameter of the anastomosis. Longitudinal enterotomies are performed on the antimesenteric aspect followed by creation of the anastomosis transversely in a handsewn fashion with single-layer running sutures resulting in a large anastomosis [11]. This innovative concept excludes the mesentery from the anastomosis site while maintaining its vascularization and innervation.

The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to evaluate the safety of the Kono-S anastomosis technique and assess the postoperative clinical, endoscopic, and surgical recurrence rates.

Methods

Search strategy and data sources

A comprehensive search of MEDLINE (PubMed), Embase (Elsevier), Scopus (Elsevier), and Cochrane Central (Ovid). databases from inception to August 24th, 2023, was conducted. The search strategy, designed and conducted by a medical reference librarian, involved keywords and controlled vocabulary for concepts including “Kono-S, anastomosis”, “functional end to end”, “Crohn’s disease”, “inflammatory bowel disease”, “enteritis regionalis” and “morbus Crohn”. The review was registered prospectively with PROSPERO (CRD42023475406). Database results were uploaded into Covidence review software where deduplication took place. In accordance with Cochrane systematic review guidelines, two reviewers (MM and DV) screened titles, abstracts and full texts based on the eligibility criteria below and conflicts were resolved by an independent third reviewer (BS).

Eligibility criteria and quality assessment

Eligible studies must have met all the following inclusion criteria: (1) participants older than 18 years with Crohn’s disease; (2) participants undergoing bowel resection and subsequently Kono-S anastomosis technique; (3) studies reporting primary outcomes of clinical, surgical or endoscopic recurrence, complications/adverse events, or anastomosis leakage following the procedure. Randomized control trials, prospective and retrospective cohort studies, case series, abstracts and poster presentations were included. The methodological quality of each study was independently evaluated by two authors using the ROBINS-I tool for non-randomized studies and ROB2 tool for randomized studies [12, 13].

Statistical analysis

For single-arm analyses, means of continuous variables and rates of binary variables were pooled using the random-effects model, generic inverse variance method of Der Simonian, Laird [14]. Proportions underwent logit transformation prior to meta-analysis. For two-arm analyses, pooled means and proportions were analyzed using an inverse variance method for continuous data and the Mantel-Haenszel method for dichotomous data. The weight of each study was assigned based on its variance. The heterogeneity of effect size estimates across the studies was quantified using the Q statistic and the I2 index (P < 0.10 was considered significant). A value of I2 of 0–25% indicates minimal heterogeneity, 26–50% moderate heterogeneity, and 51–100% substantial heterogeneity. Furthermore, a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess each study’s influence on the pooled estimate by omitting one study at a time and recalculating the combined estimates for the remaining studies. Data analysis was performed using Open Meta analyst software (CEBM, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, USA) for single arm analyses and RevMan software version 5.4 (Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program] The Cochrane Collaboration, 2020, Copenhagen, Denmark) for two-arm analyses. If mean or standard deviation (SD) was unavailable, the median was converted to mean and the range, interquartile range or confidence intervals were converted to SD using the formulas from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [15].

Endpoints

Endoscopic recurrence was reported as Rutgeert Score ≥ i2 and mean score ranged from i0–i4 [7]. Clinical recurrence was defined as patient-reported recurrence of symptoms or Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) > 200. Surgical recurrence was defined as reoperation with resection for recurrence of disease. Other endpoints included anastomotic leakage or insufficiency, defined as radiographic evidence of a leak from the anastomosis and included both symptomatic and asymptomatic cases. Anastomotic reintervention was defined as short term postoperative reoperation due to anastomotic leakage or insufficiency. Ileus was defined as the presence of obstructive or paralytic postoperative ileus. Infection, explained as pooled rates of wound infection, intraabdominal infection, and intraabdominal abscess was also analyzed. Biologic use preoperatively and postoperatively was also collected and analyzed.

Results

Study selection

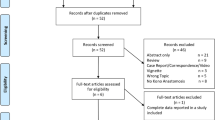

The initial search yielded 157 potentially relevant articles from which 12 unique studies involving 820 patients met the eligibility criteria [11, 16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. The details of the study selection process and PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses) flow diagram are depicted in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Risk of bias

Results of the quality assessment of all included studies are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. In ROBINS-1, 11 studies were judged to have moderate risk of bias [11, 17,18,19,20,21,22,23, 25, 26], while one study was judged to have serious risk of bias [16]. In ROB2, one study was judged to have some concern for overall risk of bias [24].

Baseline and procedural characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the included studies are comprehensively described in Table 1. 820 patients underwent 822 Kono-S anastomoses. The pooled proportion of female patients was 41.9% (n = 756; 95% CI: 33.5, 50.8; I2 = 77.9%) [11, 17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. The mean age of participants was 33.9 years (n = 756; 95% CI: 30.1, 37.7; I2 = 97.5%) [11, 17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26], and the pooled mean BMI was 21.97 kg/m2 (n = 574; 95% CI: 19.5, 24.5; I2 = 98.0%) [17, 19,20,21,22, 26]. The pooled proportion of active smokers was 21.9% (n = 701; 95% CI: 15.7, 29.6; I2 = 74.5%) [11, 17, 19,20,21,22,23,24, 26]. The pooled proportion of patients that had previous abdominal surgery was 33.9% (n = 512; 95% CI: 23.6, 46; I2 = 79.7%) [11, 17,18,19, 21,22,23,24]. Procedural characteristics of patients undergoing the Kono-S procedure are shown in Table 2. The total mean operative time was 215.0 min (n = 665; 95% CI: 138.8, 291.2; I2 = 99.8%) [17,18,19,20,21,22, 24,25,26], and the mean hospital stay was 9.3 days (n = 548; 95% CI: 7.2, 11.5; I2 = 97.4%) [17,18,19,20,21,22, 24, 25]. In the pooled proportions of surgical approach, 35.2% of procedures were open surgeries (n = 570; 95% CI: 22.6, 50.4; I2 = 87.1%) [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25], and 64.7% were laparoscopic surgeries (n = 570; 95% CI: 50.6, 76.6; I2 = 85.5%) [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25], while 5.6% of surgeries were converted from laparoscopic to open (n = 168; 95% CI: 2.7, 11.3; I2 = 0%) [17, 18, 22, 23, 25]. In the pooled proportions of type of anastomosis, 88.3% were small-to-large bowel (n = 743; 95% CI: 72.7, 95.6; I2 = 93.6%) [11, 17,18,19,20,21,22,23, 25, 26], 11.0% were small-to-small bowel (n = 743; 95% CI: 4.3, 25.3; I2 = 92.9%) [11, 17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25], and 3.1% were large-to-large bowel anastomoses (n = 743; 95% CI: 1.7, 5.6; I2 = 14.9%) [11, 17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. The pooled proportion of patients that completed follow up was 98.3% (n = 756; 95% CI: 94.9, 99.5; I2 = 59.2%) with a pooled mean follow-up time of 22.8 months (n = 758; 95% CI: 15.8, 29.9; I2 = 99.8%) [11, 17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. Pooled preoperative biologic use was 50.5% (n = 657; 95% CI: 36.2, 64.8; I2 = 89.0%) [17,18,19,20,21, 23,24,25,26] and postoperative biologic use was 49.8% (n = 411; 95% CI: 41.4, 58.1; I2 = 58.7%) [11, 17, 18, 20, 22,23,24, 26]. No difference was found between the two groups when comparing biologic use preoperatively and postoperatively (OR = 1.26; 95% CI: 0.46, 3.46; I2 = 84%, p = 0.65) [17, 18, 20, 23, 24, 26].

Outcomes of kono-S procedure

Outcomes of the Kono-S procedure are outlined in Table 3. The pooled clinical recurrence was 26.8% (n = 374; 95% CI: 14, 45.1; I2 = 84.9%) [17, 19, 24, 25]. The pooled surgical recurrence rate was 3.9% (n = 666; 95% CI: 2.2, 6.9; I2 = 25.97%) [11, 18,19,20,21,22, 24,25,26]. The pooled endoscopic recurrence rate was 24.1% (n = 510; 95% CI: 9.4, 49.3; I2 = 93.43%) [11, 17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. The pooled mean Rutgeert score measured in 157 patients at follow up was 1.54 (95% CI: 0.51, 2.57; I2 = 97.4%) [11, 22,23,24]. Recurrence rates are depicted in Fig. 1. The pooled anastomosis leakage rate was 2.9% (n = 822; 95% CI: 1.8, 4.5; I2 = 0%) [11, 16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. The pooled rate of patients requiring reoperation for complications or anastomotic leakage was 2.2% (n = 637; 95% CI: 0.8, 5.9; I2 = 50.4%) [11, 18,19,20,21,22, 25, 26]. The most common complication was infection, with a pooled rate of 11.5% (n = 822; 95% CI: 4.4, 27.0; I2 = 90.8%) followed by ileus with a pooled rate of 10.9% of participants (n = 612; 95% CI: 7.6, 15.4; I2 = 31.6%) [11, 18,19,20, 22,23,24, 26]. 261 total complications were recorded with a pooled proportion of 33.7% (n = 756; 95% CI: 20.6, 49.8; I2 = 90.5%) [11, 17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. Complication, anastomotic leakage, and reintervention rates are comprehensively shown in Fig. 2.

Discussion

Initial Crohn’s disease (CD) recurrence has been shown to occur proximal to the surgical anastomosis [27, 28], with histopathological inflammatory changes detected as early as 1 week postoperatively [29]. As a result, from a surgical perspective there has been an increasing focus on the choice of resection and anastomotic techniques. Our study demonstrated a postoperative endoscopic recurrence rate of 24.1%, which is lower than that reported in a study assessing patients receiving a conventional anastomosis, with a recurrence rate of 42.6% [28]. This indicates that the Kono-S anastomosis may have a protective role in endoscopic recurrence and CD progression at the anastomotic site. However, this observed difference is debatable due to a lack of comparative studies and long term follow up in our population and the remaining literature. Our study’s pooled follow-up period was 22.8 months; however, the heterogeneity of follow-up in included studies was considerable at 99% due to varied monitoring lengths and the lack of standardized follow-up protocols. In addition, there is a possibility that our recurrence rates were underestimated since some studies reported recurrence as Rutgeerts score ≥ i2 while others reported is as > i2. Surgical recurrence remains important in ileocolic disease with estimated rates of recurrence requiring re-operation of 11–32% at 5 years and 46–55% at 20 years [8]. A randomized controlled trial comparing handsewn, and stapled end-to-end anastomoses in 63 patients reported surgical recurrence rates of 7.5% and 5% at 24 months, respectively [30]. Additionally, a prospective study in 30 patients indicated that side-to-side anastomoses resulted in recurrence rates ranging from 0 to 4% over the same follow-up period [31]. When compared to our recurrence rate of 3.9% at 22.8 months, the observable differences are minimal, and conclusions are difficult to draw due to the small sample size. These findings underscore the necessity for large-scale, comparative randomized trials to further investigate these outcomes. Our study also demonstrated a pooled rate of clinical recurrence of 26.8% in 374 patients at follow up, but results were deemed to have high heterogeneity. In population-based studies, the clinical recurrence rate ranged from 28 to 45% and 36–61% at 5 and 10 years, respectively [32]. However, it is difficult to judge the clinical recurrence rate in our study due to a low sample size and unstandardized definitions of clinical recurrence across studies.

It is important to consider postoperative use of biologics and other immunomodulators as prophylaxis for recurrence. Our study demonstrated that there was no difference between biologic administration rates pre- and post-operatively, however, our findings are limited by high heterogeneity. Although this could indicate that recurrence rates observed were mainly influenced by Kono-S technique, the effect of other pertinent risk factors including active smoking or previous abdominal surgery could not be isolated in our study.

The total rate of complications in our meta-analysis was 33.7%. In contrast, other studies showed a 23% complication rate in stapled side-to-side anastomosis and a 21–24% rate in end-to-end anastomosis [10, 33]. However, several comparative cohort and randomized studies showed either no difference or significantly reduced complication rates in Kono-S anastomosis when compared to other surgical techniques [11, 17, 21, 23, 24, 26]. Given the high heterogeneity in the data (90%) and large confidence intervals, a larger sample size and more studies are required to get a more representative rate.

Regarding anastomotic leak, our study reported a rate of 2.9%. Other studies examining anastomotic insufficiency have shown a 4–7% leak rate in stapled side-to-side anastomosis and a 7-8.6% rate in end-to-end anastomosis [10, 33, 34]. This is an observable difference that has been corroborated by a randomized trial and comparative cohort studies [11, 24, 26]. However, it is difficult to determine clinical significance due to the low number of patients in the current study and the rare nature of this complication; thus, large, multi-center randomized trials are required to elucidate any potential difference, although they may not be feasible as additional factors such as surgeon preference, increasing number of medical therapies along with decreasing rates of surgical interventions may render a randomized trial unfeasible [35]. The most common complication in our study was infection occurring in 11.5% followed by ileus in 11%. A systematic review revealed similar rates of postoperative ileus after colorectal surgery, occurring in 10% [36]. The pooled rate in our study is higher than that reported in the literature examining other anastomotic techniques, and this could be explained by the prolonged duration of the Kono-S operation and exposure to anesthesia when compared to traditional anastomotic techniques [37]. In our study, the mean duration of operation was 215 min and was observably longer than stapled side-to-side (113 min) and end-to-end anastomosis (138 min) [33]. This longer duration can be attributed to the novel nature and learning curve of the technique, which also contributes to the increased heterogeneity in our data. Regarding total hospital stay, our study reported an average of 9.3 days, with significant heterogeneity. Notably, a leave-one-out analysis with the exclusion of Eto et al., [18] yielded a result of 6.8 days, which is comparable to the literature on side-to-side and end-to-end anastomoses [10, 24, 33, 38].

Several factors related to anastomoses have been postulated to play a role in disease recurrence. First, a growing body of research has demonstrated that mesenteric organs, such as adipose tissue, lymphatics, blood vessels, and mesenteric nerves play a critical role in the etiology and progression of CD [19]. The involvement of the mesentery has largely been thought to be secondary to CD, but recent literature has demonstrated evidence of mesenteric abnormalities detected prior to any mucosal changes can subsequently predict development of CD [39]. This was further confirmed by a retrospective study showing that excision of the mesentery significantly reduced reoperation rates [40]. Even though the mesentery is preserved in the Kono-S technique, the antimesenteric lumen and the posterior supporting column that excludes the mesentery from the lumen itself could be a contributing factor to the reduction in recurrence rates, as demonstrated in the current study [19]. Second, the effect of lumen size and configuration on enteric flow has recently gained popularity. Since fecal stasis is suspected to influence mucosal healing and has been linked to disease recurrence [17, 26], ECCO Guidelines currently advocate carrying out a wide ileo-colic anastomosis [41]. The antimesenteric configuration of the Kono-S anastomosis results in a consistently wide lumen (7 cm diameter) and prevents unnecessary denervation or devascularization of the anastomotic site [11]. This supports the healing process and lessens the risk of secondary ischemia, early stenosis, colonic reflux, and fecal stasis [42]. Moreover, by stabilizing the lumen, the posterior column prevents distortion and reduces the likelihood of enteric flow impediments [11]. The Kono-S anastomosis positively benefits endoscopists by increasing the feasibility of endoscopic monitoring and intervention, as the wide lumen at the anastomotic site and the supporting column maintain a three-dimensional structure [21]. Last, there is evidence linking postoperative complications, particularly septic complications, to a higher chance of recurrence [19, 43]. The safety of the Kono-S technique, as demonstrated by the low rates of anastomotic leakage and infection in our meta-analysis, may further contribute to reduced recurrence rates.

This meta-analysis builds on the foundation laid by previously published systematic reviews [44, 45]. While acknowledging the valuable contributions of previous work, our meta-analysis addressed limitations of overlapping populations and the need for continual updates when evaluating a new surgical technique such as the Kono-S anastomosis. In addition, 11 studies were excluded due to the possibility of shared participants and six new articles that were not previously included in any systematic reviews were added. These changes enhanced generalizability, statistical power, and reliability and reduced potential bias.

Several limitations must be taken into consideration. First, the majority of included studies were retrospective in design, which removed the possibility of randomization and introduced selection bias. Second, the reproducibility of the results was reduced since most studies were conducted in a single center. Furthermore, the high heterogeneity in follow up periods between studies limits the conclusions drawn about recurrence rates in the studied population. Moreover, the occurrence of various types of anastomoses, such as small to large bowel, large to large bowel, and small to small bowel, in our investigated population introduces bias into our results. In addition, we were unable to assess the difference between emergency and ambulatory indications, which could introduce a confounding bias in the studied population. Finally, this procedure is relatively novel and requires surgical expertise. Since the ability to assess the surgeon’s learning curve and skills for Kono-S anastomosis was not possible, heterogeneity and bias in the results should be taken into account. Despite these limitations, to our knowledge, this is one of the largest and most comprehensive studies available in the literature. It demonstrates that the Kono-S anastomosis in Crohn’s patients undergoing surgical resection could be a possible alternative to other techniques.

In summary, this meta-analysis presents preliminary evidence evaluating the safety and effectivity of the Kono-S procedure in Crohn’s disease patients undergoing ileocolic resection. Despite limited data in this meta-analysis, there appears to be a relatively low rate of surgical recurrence, and a relatively moderate rate of endoscopic and clinical recurrence in patients undergoing Kono-S. Moreover, there appears to be a promising trend suggesting a moderate complication rate and a low anastomotic leakage rate. Given the results, further studies with increased sample sizes and longer follow up are required to elucidate the safety and effectivity of Kono-S technique.

Data availability

With the publication, the data set used for this meta-analysis will be shared upon request from the corresponding authors.

References

Rispo A, Imperatore N, Testa A et al (2018) Combined Endoscopic/Sonographic-based risk Matrix Model for Predicting one-year risk of surgery: a prospective observational study of a tertiary centre Severe/Refractory Crohn’s Disease Cohort. J Crohns Colitis 12(7):784–793. https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjy032

Floyd DN, Langham S, Séverac HC, Levesque BG (2015) The Economic and Quality-of-life Burden of Crohn’s Disease in Europe and the United States, 2000 to 2013: a systematic review. Dig Dis Sci 60(2):299–312. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-014-3368-z

Bouguen G, Levesque BG, Feagan BG et al (2015) Treat to target: a proposed New Paradigm for the management of Crohn’s Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 13(6):1042–1050e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2013.09.006

Crohn BB, Hinzburg L, Oppenheimer GD (1932) Regional Ileitis A pathologic and clinical entity. JAMA 99(16):1323

Singh S, Murad MH, Fumery M et al (2021) Comparative efficacy and safety of biologic therapies for moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 6(12):1002–1014. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00312-5

Frolkis AD, Dykeman J, Negrón ME et al (2013) Risk of surgery for inflammatory Bowel diseases has decreased over time: a systematic review and Meta-analysis of Population-Based studies. Gastroenterology 145(5):996–1006. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2013.07.041

Rutgeerts PG, Geboes K, Vantrappen G, Beyls J, Kerremans R, Hiele M (1990) Predictability of the postoperative course of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 99(4):956–963. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-5085(90)90613-6

Yamamoto T (2005) Factors affecting recurrence after surgery for Crohn’s disease. World J Gastroenterol 11(26):3971. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i26.3971

Click B, Merchea A, Colibaseanu DT, Regueiro M, Farraye FA, Stocchi L (2022) Ileocolic Resection for Crohn Disease: the influence of different Surgical techniques on Perioperative outcomes, Recurrence Rates, and endoscopic surveillance. Inflamm Bowel Dis 28(2):289–298. https://doi.org/10.1093/ibd/izab081

Simillis C, Purkayastha S, Yamamoto T, Strong SA, Darzi AW, Tekkis PP (2007) A Meta-analysis comparing conventional end-to-end anastomosis vs. other anastomotic configurations after resection in Crohn’s Disease. Dis Colon Rectum 50(10):1674–1687. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10350-007-9011-8

Kono T, Ashida T, Ebisawa Y et al (2011) A New Antimesenteric Functional End-to-end Handsewn Anastomosis: Surgical Prevention of Anastomotic recurrence in Crohn’s Disease. Dis Colon Rectum 54(5):586–592. https://doi.org/10.1007/DCR.0b013e318208b90f

Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ et al (2019) RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ Published Online August 28:l4898. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l4898

Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC et al (2016) ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ Published Online Oct 12:i4919. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i4919

DerSimonian R, Laird N (1986) Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 7(3):177–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2

Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J et al ochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.4. Cochrane

Adamou A, Müller G, Iesalnieks I (2022) Implementation of Kono-S anastomosis as a new standard of surgical care. J Crohns Colitis 16:i488 /S1(Abstracts of the 17th Congress of ECCO))

Alibert L, Betton L, Falcoz A et al (2023) DOP78 does KONO-S anastomosis reduce recurrence in Crohn’s disease compared to conventional ileocolonic anastomosis ? A nationwide propensity score-matched study from GETAID Chirurgie Group (KoCoRICCO study). J Crohns Colitis 17(Supplement1):i155–i155. https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjac190.0118

Eto S, Yoshikawa K, Iwata T et al (2019) Kono-S anastomosis for Crohn’s Disease: report of 2 cases. Int Surg 104(11–12):534–539. https://doi.org/10.9738/INTSURG-D-15-00076.1

Fichera A, Mangrola A, Olortegui KS et al (2023) Long-term outcome of the Kono-S anastomosis: a Multicenter Study. Dis Colon Rectum. Published Online November 20. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0000000000003132

Holubar SD, Lipman J, Steele SR et al (2023) Safety feasibility of targeted mesenteric approaches with Kono-S anastomosis and extended mesenteric excision in ileocolic resection and anastomosis in Crohn’s disease. Am J Surg Published Online Oct. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2023.10.050

Horisberger K, Birrer DL, Rickenbacher A, Turina M (2021) Experiences with the Kono-S anastomosis in Crohn’s disease of the terminal ileum—a cohort study. Langenbecks Arch Surg 406(4):1173–1180. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-020-01998-6

Katsuno H, Maeda K, Hanai T, Masumori K, Koide Y, Kono T (2015) Novel antimesenteric functional end-to-end Handsewn (Kono-S) Anastomoses for Crohn’s disease: a Report of Surgical Procedure and short-term outcomes. Dig Surg 32(1):39–44. https://doi.org/10.1159/000371857

Kelm M, Reibetanz J, Kim M et al (2022) Kono-S Anastomosis in Crohn’s Disease: a retrospective study on postoperative morbidity and disease recurrence in comparison to the conventional Side-To-Side anastomosis. J Clin Med 11(23):6915. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11236915

Luglio G, Rispo A, Imperatore N et al (2020) Surgical Prevention of Anastomotic recurrence by excluding mesentery in Crohn’s Disease: the SuPREMe-CD study - A Randomized Clinical Trial. Ann Surg 272(2):210–217. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000003821

Seyfried S, Post S, Kienle P, Galata CL (2019) The Kono-S anastomosis in surgery for Crohn’s disease : first results of a new functional end-to-end anastomotic technique after intestinal resection in patients with Crohn’s disease in Germany. Chirurg 90(2):131–136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00104-018-0668-4

Shimada N, Ohge H, Kono T et al (2019) Surgical recurrence at Anastomotic Site after Bowel Resection in Crohn’s Disease: comparison of Kono-S and End-to-end anastomosis. J Gastrointest Surg 23(2):312–319. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-018-4012-6

De Cruz P, Kamm MA, Prideaux L, Allen PB, Desmond PV (2012) Postoperative recurrent luminal Crohnʼs disease: a systematic review. Inflamm Bowel Dis 18(4):758–777. https://doi.org/10.1002/ibd.21825

Nardone OM, Calabrese G, Barberio B et al (2023) Rates of endoscopic recurrence in postoperative Crohn’s Disease based on anastomotic techniques: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. Published Online November 1. https://doi.org/10.1093/ibd/izad252

D’Haens GR, Geboes K, Peeters M, Baert F, Penninckx F, Rutgeerts P (1998) Early lesions of recurrent Crohn’s disease caused by infusion of intestinal contents in excluded ileum. Gastroenterology 114(2):262–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-5085(98)70476-7

Ikeuchi H, Kusunoki M, Yamamura T (2000) Long-term results of Stapled and Hand-Sewn anastomoses in patients with Crohn’s Disease. Dig Surg 17(5):493–496. https://doi.org/10.1159/000051946

Chen W, Zhou J, Chen M, Jiang C, Qian Q, Ding Z (2022) Isoperistaltic side-to-side anastomosis for the surgical treatment of Crohn disease. Ann Surg Treat Res 103(1):53. https://doi.org/10.4174/astr.2022.103.1.53

Buisson A, Chevaux J-B, Allen PB, Bommelaer G, Peyrin‐Biroulet L (2012) Review article: the natural history of postoperative < scp > C rohn’s disease recurrence. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 35(6):625–633. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05002.x

McLeod RS, Wolff BG, Ross S, Parkes R, McKenzie M (2009) Recurrence of Crohn’s Disease after Ileocolic Resection is not affected by Anastomotic Type. Dis Colon Rectum 52(5):919–927. https://doi.org/10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181a4fa58

He X, Chen Z, Huang J et al (2014) Stapled side-to-side anastomosis might be Better Than Handsewn End-to-end anastomosis in Ileocolic Resection for Crohn’s Disease: a Meta-analysis. Dig Dis Sci 59(7):1544–1551. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-014-3039-0

Vu M, Ghosh S, Umashankar K et al (2023) Comparison of surgery rates in biologic-naïve patients with Crohn’s disease treated with vedolizumab or ustekinumab: findings from SOJOURN. BMC Gastroenterol 23(1):87. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-023-02723-5

Wolthuis AM, Bislenghi G, Fieuws S, de Buck van Overstraeten A, Boeckxstaens G, D’Hoore A (2016) Incidence of prolonged postoperative ileus after colorectal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Colorectal Dis 18(1). https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.13210

Asgeirsson T, El-Badawi KI, Mahmood A, Barletta J, Luchtefeld M, Senagore AJ (2010) Postoperative ileus: it costs more than you expect. J Am Coll Surg 210(2):228–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.09.028

Guo Y, Hormel TT, Pi S et al (2021) An end-to-end network for segmenting the vasculature of three retinal capillary plexuses from OCT angiographic volumes. Biomed Opt Express 12(8):4889. https://doi.org/10.1364/BOE.431888

Wickramasinghe D, Warusavitarne J (2019) The role of the mesentery in reducing recurrence after surgery in Crohn’s disease. Updates Surg 71(1):11–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-019-00623-6

Coffey CJ, Kiernan MG, Sahebally SM et al (2018) Inclusion of the Mesentery in Ileocolic Resection for Crohn’s Disease is Associated with reduced Surgical recurrence. J Crohns Colitis 12(10):1139–1150. https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx187

Gionchetti P, Dignass A, Danese S et al (2017) 3rd European evidence-based Consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s Disease 2016: part 2: Surgical Management and Special situations. J Crohns Colitis 11(2):135–149. https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw169

Petagna L, Antonelli A, Ganini C et al (2020) Pathophysiology of Crohn’s disease inflammation and recurrence. Biol Direct 15(1):23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13062-020-00280-5

Iesalnieks I, Kilger A, Glaß H et al (2008) Intraabdominal septic complications following bowel resection for Crohn’s disease: detrimental influence on long-term outcome. Int J Colorectal Dis 23(12):1167–1174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-008-0534-9

Ng CH, Chin YH, Lin SY et al (2021) Kono-S anastomosis for Crohn’s disease: a systemic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Surg Today 51(4):493–501. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-020-02130-3

Alshantti A, Hind D, Hancock L, Brown SR (2021) The role of Kono-S anastomosis and mesenteric resection in reducing recurrence after surgery for Crohn’s disease: a systematic review. Colorectal Dis 23(1):7–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.15136

Funding

Not applicable.

Open access funding provided by University of Basel

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AT conceived and designed the study. AT and RR supervised the study. MM, DV, BS reviewed the literature. MM, DV, BS, collected, and interpreted the data. NO and BS analyzed the data. MC, BS, NEG drafted the manuscript. CT, MDH, EB, KN, RR, ST-M, CG, AH, AT reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

This systematic review and meta-analysis does not require ethical approval.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cathomas, M., Saad, B., Taha-Mehlitz, S. et al. Safety and effectivity of Kono-S anastomosis in Crohn’s patients: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Langenbecks Arch Surg 409, 227 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-024-03412-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-024-03412-x