Abstract

The aim of this randomized controlled trial was to assess changes in myalgic trapezius activation, muscle oxygenation, and pain intensity during repetitive and stressful work tasks in response to 10 weeks of training. In total, 39 women with a clinical diagnosis of trapezius myalgia were randomly assigned to: (1) general fitness training performed as leg-bicycling (GFT); (2) specific strength training of the neck/shoulder muscles (SST) or (3) reference intervention without physical exercise. Electromyographic activity (EMG), tissue oxygenation (near infrared spectroscopy), and pain intensity were measured in trapezius during pegboard and stress tasks before and after the intervention period. During the pegboard task, GFT improved trapezius oxygenation from a relative decrease of −0.83 ± 1.48 μM to an increase of 0.05 ± 1.32 μM, and decreased pain development by 43%, but did not affect resting levels of pain. SST lowered the relative EMG amplitude by 36%, and decreased pain during resting and working conditions by 52 and 38%, respectively, without affecting trapezius oxygenation. In conclusion, GFT performed as leg-bicycling decreased pain development during repetitive work tasks, possibly due to improved oxygenation of the painful muscles. SST lowered the overall level of pain both during rest and work, possibly due to a lowered relative exposure as evidenced by a lowered relative EMG. The results demonstrate differential adaptive mechanisms of contrasting physical exercise interventions on chronic muscle pain at rest and during repetitive work tasks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Neck/shoulder pain—and especially trapezius myalgia—is frequent in females employed in repetitive stressful jobs (Larsson et al. 2007). Pain in the trapezius muscle has been shown to be associated with various mitochondrial changes in type 1 muscle fibers as well as reduced capillarization per fiber cross-sectional area (Kadi et al. 1998; Larsson et al. 2000, 2004), pointing towards a relation between metabolic insufficiencies and pain. This is supported first by the finding of an increased anaerobic metabolism and second by a larger and more sustained oxygen deficit during the start of a work task in myalgic subjects compared with healthy controls (Sjøgaard et al. 2010; Rosendal et al. 2004b). Further, among healthy subjects, trapezius muscle pain development during a work task seems to be related to regulation of blood flow (Strom et al. 2009).

Specific strength training of the painful muscle has been shown to be effective in decreasing levels of pain at rest (Andersen et al. 2008; Ylinen et al. 2003; Ahlgren et al. 2001). However, regarding pain development during a work task, the effect of interventions with different types of exercise is unknown. It is plausible that other types of exercise than specific strength training can have an indirect positive effect on pain development during work. General fitness trainings such as bicycling and jogging are acceptable forms of exercise for many people. Although such types of exercise do not directly involve the painful trapezius muscle, it is possible that exercising large muscle groups may improve the oxygenation of distant relaxed muscles. The prevailing view is that blood flow to inactive tissue decreases during exercise due to increased sympathetic nervous activity (Ohlsson et al. 1994; McAllister 1998; Perko et al. 1998). Nevertheless, increased blood flow to non-working muscles during aerobic exercise by improved endothelium-dependent vasodilatation has also been reported (DeSouza et al. 2000). Supporting this, vascular adaptations have been shown to occur in the vascular beds of the forearm muscles in response to lower extremity conditioning training (Silber et al. 1991). Also, improved endothelial vasodilatory capacity in conduit arteries of the non-working limb has been observed in response to exercise with the contra lateral limb (Tanaka et al. 2006). In accordance with these studies, we have recently shown that leg-cycling with passively hanging arms enhances blood flow and oxygenation in the trapezius muscle in myalgic as well as in healthy subjects (Andersen et al. 2010). Therefore, potentially, this improved oxygenation of the relaxed muscles during exercise could have an indirect beneficial effect on pain development during work tasks involving the myalgic trapezius muscle. The aim of this randomized controlled trial was to assess changes in myalgic trapezius activation, muscle oxygenation, and pain intensity during repetitive and stressful work tasks in response to 10 weeks of: (1) training in terms of leg-bicycling with relaxed shoulders; (2) specific strength training locally for the affected muscle or (3) a reference intervention without physical activity. It was hypothesized that both types of physical training would be superior to the reference intervention with regard to improved oxygenation and reduction in pain intensity in the myalgic muscle.

Materials and methods

Study design

A randomized controlled trial with short-term effect measured immediately after the 10 weeks intervention was performed in Copenhagen, Denmark. The participants were women, aged 30–60 years, recruited via seven workplaces (2 banks, 2 post office work places, 2 different national administrative offices and 1 industrial production unit) or via announcement in local newspapers. The typical work tasks of the participants were monotonous and repetitive, e.g., assembly line work, office work and the majority performed computer typing. The procedure of recruitment has recently been described in detail (Andersen et al. 2008). Briefly, 812 female workers were invited to participate in the study, 530 replied to the invitation by answering a screening questionnaire to identify workers with trapezius myalgia. Three hundred and sixteen were willing to participate, and of these, 147 fulfilled the inclusion criteria: (1) trouble (pain and discomfort) for more than 30 days during the last year in the neck/shoulder region; (2) not more than 30 days of trouble in maximally three body regions out of eight major body regions (neck/shoulder, low back, left or right arm/hand, hip, knee/foot) to exclude generalized musculoskeletal diseases; (3) the trouble should be at least “quite a lot” on an ordinal 5-step scale ranging from “a little” to “very much”; (4) the trouble should be frequent (at least once a week) and (5) the intensity of the trouble should be at least 2 on a scale from 0 to 9, where 0 is “no pain” and 9 is “worst imaginable pain”. Additionally, none of the participants should suffer from serious conditions such as previous trauma or injuries, life threatening diseases, cardiovascular diseases, or arthritis in the neck and shoulder. The 147 workers who fulfilled the inclusion criteria based on the screening questionnaire were invited to a neck and upper limb clinical examination originally developed by Ohlsson et al. (1994) and later modified as described in detail by Juul-Kristensen et al. (2006). Briefly, the main criteria for a positive clinical diagnosis of trapezius myalgia were: (1) pain in the neck area; (2) tightness of the trapezius muscle and (3) palpable tenderness in the trapezius muscle. Those who based on this examination qualified for trapezius myalgia and did not show contraindications (n = 43) were invited for the study. Results from this intervention trial on maximal muscle activation, muscle strength and morphology as well as perceived pain measures have been reported earlier (Andersen et al. 2008, 2009; Nielsen et al. 2010) in addition to baseline data from trapezius myalgia cases compared with healthy controls on muscle activation, oxygenation, metabolites, biochemistry and pain (Sjøgaard et al. 2010; Mackey et al. 2010). The present paper focuses on the short-term intervention effects on muscle activation, oxygenation, and pain development during a repetitive work task with measurements of tissue oxygenation obtained from 39 out of the 43 participants. The intervention trial also includes data on muscle endurance, metabolism and histochemistry; however, these results will be dealt with in future publications.

All participants were informed about the purpose and content of the project and gave written informed consent to participate in the study, which was conformed to The Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the Local Ethical Committee (KF 01-138/04). The study was qualified for registration in the International Standard Randomized Controlled Trial Number Register: ISRCTN87055459.

Interventions

All three interventions lasted 10 weeks. The randomization to one of the three groups was done at the cluster level in a balanced design accounting for similar age, BMI, and screening questionnaire based on neck/shoulder trouble. The three intervention groups were: (1) general fitness training in terms of leg-bicycling with relaxed shoulders (GFT); (2) specific strength training locally for the affected muscle (SST) or (3) a reference intervention without physical activity (REF). Due to the randomization procedure, no difference between groups was observed with regard to age, height, and body mass (GFT: 45.5 ± 8.0 years, 1.67 ± 0.05 m, 74.8 ± 18.7 kg; SST: 44.6 ± 8.5 years, 1.67 ± 0.06 m, 71.6 ± 11.4 kg; REF: 42.5 ± 11.1 years, 1.69 ± 0.09 m, 67.7 ± 14.0 kg). In all groups, total time allowed to spend on the project equated 1 h per week. SST and GFT performed 10 weeks supervised training consisting of three sessions of 20 min per week. REF was also allowed a total of 1 h per week, but met more irregularly.

GFT (n = 15) high-intensity general fitness training was performed on a bicycle ergometer for 20 min at a relative workload of 50–70% VO2max. Initial training sessions started at 50% VO2max and progressively increased to 70% VO2max throughout the training period. The participants bicycled in an upright position without holding on to the handlebars; it was emphasized that the participants should relax the shoulders during training. During each training session, heart rate was recorded in each subject by a heart rate monitor (Polar Sport Tester, Kempele, Finland) to adjust the workload to the intended relative level.

SST (n = 16) specific strength training was performed for the neck and shoulder muscles with five different dumbbell exercises (1-arm row, shoulder abduction, shoulder elevation, reverse flies, upright row). During the intervention period, the relative loadings were progressively increased from 12 repetitions maximum (RM) (~70% of maximal intensity) towards eight RM (~80% of maximal intensity). Three of the five exercises were performed during each training session with three sets per exercise, each set typically lasting 25–35 s.

REF (n = 8) this group was not offered any physical training but received an equal amount of attention as the physical training intervention groups. The participants received health counseling on group and individual level regarding workplace ergonomics, diet, health, relaxation, and stress management. Unfortunately, the time-wise successive balanced recruitment resulted in a smaller REF group, e.g., due to withdrawal of participants who initially stated that they would volunteer for the study.

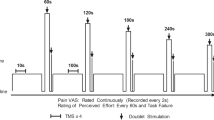

Pegboard and stress task

On two experimental workdays before the 10 weeks intervention period started and within 2–5 days after the end of the intervention, respectively, the participants performed two work tasks in a seated position. A standardized repetitive task consisted of 40 min pegboard work as described previously (Sjøgaard et al. 2010). The pegboard work was interrupted every 5 min for inquiring about pain intensity (VAS) and rate of perceived exertion (RPE), thus a total of 8 × 5 min sessions were performed.

Following the pegboard task, the participants rested for 120 min before the stress task was performed. The Stroop test, alternatively termed ‘the color word conflict task’ (Frankenhaeuser and Johansson 1976), was used as a work task to stress the participants and was performed on a computer with a mouse—operated by the same hand as the PEG—for 10 min.

Measurements

Measurements on the trapezius muscle were performed on the most affected side in case of side difference in pain intensity and otherwise on the dominated side.

Electromyography (EMG) and mechanomyography (MMG)

EMG and MMG were recorded during the pegboard and stress task by bipolar surface electrodes (Ag–AgCl electrodes, type 700 01-K, Medicotest A/S, Ølstykke, Denmark) and by an accelerometer with 0.5 g mass (Analog Device ADXL202JE, Norwood, MA, USA) from the upper trapezius muscle. Electrodes were placed under the NIRS probe with an inter-electrode distance of 20 mm (Jensen et al. 1993). The accelerometer was placed over the lateral electrode. Signals were amplified, band-pass filtered (8th order Butterworth filter, EMG 10–400 Hz, MMG 5–100 Hz), and sampled on dataloggers (Logger Teknologi HB, Lund, Sweden) with a sampling frequency of 1,024 Hz. The signals were analyzed for root-mean-square (EMGRMS and MMGRMS) and mean power frequency values (EMGMPF and MMGMPF) during eight 5-min periods during the pegboard task and ten 1-min periods during the stress task. The EMGRMS was computed within windows of 100 ms duration and the power spectral density was calculated in 1 s intervals. The average muscle activity level during the pegboard task was judged from the EMGRMS and for evaluation of fatigue development EMGMPF and MMG measurements were included. The resting EMG signal was recorded with visual feedback from an oscilloscope to minimize the visible EMG activity during 5 s of instructed rest and subtracted from all EMG registrations. Signals were normalized to EMGRMS during a maximal voluntary isometric shoulder elevation (MVC). During the MVC, the maximal EMG amplitude (MVE) was calculated as the highest mean EMGRMS obtained with a 1 s window moving in steps of 100 ms and EMGRMS values are presented in %MVE.

Tissue oxygenation

Muscle tissue oxygenation was measured continuously during the pegboard and stress task using Near Infrared Spectroscopy (NIRS) (NIRO 300, Hamamatsu Photonics, Japan). The optodes were placed in a black rubber holder, which eliminated background light and secured the distance between light source and detector. The probe was placed at the transverse section of the upper trapezius muscle at the midpoint of the distance between acromion and C7. As a result of the thickness of the trapezius muscle and superjacent tissues (skin and fat), which is in accordance with previous studies (Rosendal et al. 2004b; Sjøgaard et al. 2004), a distance of 3 cm between light source and detector was selected giving an average light transmission depth of 1.5–2 cm (Belardinelli et al. 1995; Chance et al. 1992) to ensure that the recording site was in the trapezius muscle. The level of tissue oxygenation was sampled continuously at 2 Hz during the pegboard and stress task. The measurements were reset to zero before starting the task to reflect changes from the beginning of each exercise period.

The oxygenation measurements during the pegboard and stress tasks are presented as concentration changes in μM of O2Hb, deoxyhemoglobin (HHb), and total hemoglobin (THb). During the pegboard task, values were calculated for each participant over 30-s periods and subsequently collapsed to 3-min periods when the pegboard work was performed. NIRS values were not calculated during the first and last min of pegboard task and during 2-min periods when the pegboard work was interrupted for inquiring about pain and perceived exertion. In addition, the lowest or highest values termed nadir (O2Hb and THb) and peak (HHb) values, respectively, were identified during the first 4 min of the pegboard task. During the stress task, values over 30 s periods were calculated and subsequently collapsed to ten 1-min periods.

Blood pressure

Beat-to-beat systolic and diastolic blood pressure were measured continuously using FinometerTM Blood Pressure Monitor (TNO TPD Biomedical Instrumentations, Amsterdam, Holland) with a finger cuff placed on the middle finger of the right hand during the bicycle exercise and of the hand contra lateral to the hand performing the pegboard and stress task. The blood pressure was automatically corrected for hydrostatic pressure to compensate for vertical position of the hand with respect to heart level. The blood pressure measurements were sampled at 2.5 kHz. Data were calculated as described for measurement of tissue oxygenation over 30 s periods and subsequently collapsed to 3 min periods, omitting, the first and last min of pegboard task as well as the 2 min periods with interruption for inquiring about pain and perceived exertion. Mean arterial pressure (MAP) was calculated as: MAP = diastolic blood pressure + (systolic blood pressure − diastolic blood pressure)/3.

Pain intensity and rating of perceived exertion

Pain intensity in the shoulder region was assessed with a 100 mm VAS, ranging from 0 (no pain) to 100 mm (worst possible pain). The RPE in the shoulder region was rated according to a 10-graded Borg scale (Borg 1982), where 0 corresponded to “no perceived exertion” and 9 corresponded to “maximum perceived exertion”. The shoulder region was defined as the area covered by the trapezius, supraspinatus, and infraspinatus muscles. VAS and RPE were assessed at rest prior to the pegboard task and rated every 5th min during pegboard work (i.e., 8 times during 40 min). In addition, the rate of pain development during the pegboard task was calculated as changes in VAS slope. For the stress task, VAS and RPE were rated immediately before and after the task.

Statistics

Data are presented as mean ± 1 SD unless otherwise specified. SAS statistical software for windows (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, version 9.1) was used for all analyses. A probability of <0.05 was accepted as criteria for significance.

The dependent variables were analyzed in a repeated measures ANOVA model with time (over the pegboard and stress tasks), round (before and after intervention), and group (GFT, SST, REF) as categorical independent variables. The interaction term round*group was included in the model. Because of left-skewed distributions, the independent variables EMGRMS, EMGMPF, MMGRMS, MMGMPF, VAS, and RPE were loge-transformed before analysis (the value 1 was added to VAS and RPE before loge-transformation). The model residuals were tested for heteroscedasticity and normality. No satisfactory model could be obtained for the independent variable MMGRMS, which was therefore finally tested using the non log transformed data in a nonparametric Wilcoxon paired test comparing rounds within each group. A significant effect of the interaction term round*group was interpreted as a sign of an effect of the intervention. The intervention effect was further investigated in post hoc analysis of the changes from before to after the intervention for the three intervention groups. Post hoc p values were adjusted for multiple comparisons (Dunnet-Hsu).

Results

EMG and MMG

During the pegboard work before the intervention trapezius muscle EMGRMS and MMGRMS was as an overall mean 12.1 ± 9.3% MVE and 74.9 ± 29.7 mm s−2, respectively. The corresponding EMGMPF and MMGMPF value was 78.4 ± 20.2 and 16.0 ± 4.0 Hz, respectively. None of these values were different between groups and neither variable changed over time during the pegboard work. A short-term effect of the intervention was seen as a significant round*group effect for EMGRMS (F = 14.1 and p < 0.001) and EMGMPF (F = 19.22 and p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis showed that no changes had occurred in EMGRMS values for GFT and REF, but in SST mean trapezius muscle activity during the pegboard task decreased to 36% (p < 0.0001), while the slope remained unchanged. For EMGMPF, a 3% (p < 0.05) and a 10% (p < 0.0001) increase was seen for GFT and SST, respectively, and 8% decrease was seen for REF (p < 0.001) following the intervention. For MMGRMS, no changes were seen in any of the groups, but a significant round*group effect (F = 5.84 and p < 0.005) was found for MMGMPF. Post hoc test showed a decrease of 7% (p < 0.01) for the SST group. During the stress task before the intervention trapezius muscle EMGRMS and MMGRMS was as overall mean 5.7 ± 5.1% MVE and 46.8 ± 26.8 mm−2, respectively, and the corresponding EMGMPF and MMGMPF values were 96.6 ± 36.9 and 18.1 ± 5.4 Hz, respectively. None of these values were different between groups. After the intervention, no changes were seen for any of the EMG or MMG values during the stress task.

Tissue oxygenation

At baseline prior to the intervention, the pegboard task resulted in an initial significant decrease in O2Hb to a nadir value within the first 4 min in all groups (Table 1), and the O2Hb remained at this level throughout the pegboard working period. HHb increased initially in all groups with no difference between groups (Table 1). THb showed a significant initial decrease in all groups and remained unchanged throughout the pegboard working period (Table 1). In response to the intervention, a significant round*group effect was found in the course of O2Hb (F = 7.94, p < 0.0001), HHb (F = 4.59, p < 0.0005), and THb (F = 5.25, p < 0.0005) during the pegboard work (Fig. 1). For GFT, O2Hb and THb increased significantly (p < 0.0001 for both variables) after the intervention period compared with baseline, while no change was seen in HHb. For SST the change in HHb during the pegboard task was significantly smaller (p < 0.0001) after the intervention compared to baseline, the O2Hb tended to increase (p = 0.066), but without change in THb. No changes were seen in oxygenation for REF after the intervention period.

NIRS changes (means ± SE) in the trapezius muscle during the pegboard work task before (unfilled circles) and after (filled squares) the 10 weeks intervention period. O 2 Hb oxyhemoglobin, HHb deoxyhemoglobin, THb total hemoglobin, GFT general fitness training (n = 15), SST specific strength training (n = 16), REF reference intervention without physical activity (n = 8). Significant Intervention*round effect was found for O2Hb, HHb and THb [(DF = 6, F = 7.94, p < 0.0001), (DF = 6, F = 4.59, p < 0.0005), and (DF = 6, F = 5.25, p < 0.0002), respectively]. Asterisk indicates significant difference between before and after the intervention after post hoc analysis with adjusted p value below 0.05

At baseline, the stress task caused a significant increase in O2Hb by 2.2 ± 2.3 μM (p < 0.05) and THb by 1.7 ± 3.0 μM (p < 0.05) and HHb decreased by −0.3 ± 1.0 μM (p < 0.05) with no differences between groups. Following the intervention, no changes had occurred in the NIRS variables during the stress task.

Blood pressure

At baseline resting MAP was as an overall mean 89.1 ± 10.6 mmHg with no difference between groups. During pegboard work, MAP increased similarly in all groups to 97.9 ± 15.3 mmHg with no significant change in slope. During the stress task, MAP increased similarly in all groups to 100.7 ± 16.9 mmHg. After the 10 weeks of intervention, no changes were seen in MAP neither during the pegboard work nor during the stress test.

Pain intensity and rating of perceived exertion

At baseline prior to the intervention VAS and RPE at rest prior to the pegboard task was as an overall mean 26.6 ± 22.4 mm and 2.4 ± 1.9 points, respectively, with no difference between groups. During pegboard work, the rate of VAS and RPE development (i.e., the slope of the time curve) was positive in all three groups, and at the end of the work VAS and RPE had increased to 53.6 ± 27.7 mm (p < 0.001) and 5.6 ± 2.6 points (p < 0.001), respectively. In response to the 10 weeks intervention, a significant round*group effect (F = 16.96 and p < 0.0001) was found for VAS during the pegboard test, with decreases of 38% for SST (p < 0.0001), 34% for REF (p < 0.0001), and 20% for GFT (p < 0.01). Further, a post hoc paired t tests from baseline to after intervention was performed for each intervention group separately for the rate of pain development (i.e., the slope of the time curve). During the pegboard work, a significant 43% decrease (p < 0.01) was found only for the GFT group. In contrast, pain intensity at rest prior to the pegboard task was decreased to 52% (p < 0.05) in SST (Table 2).

Also RPE, in response to the intervention showed a significant round*group effect (F = 26.55 and p < 0.001) during the pegboard work. The overall RPE decreased to 25% for SST (p < 0.001) and 32% for GFT (p < 0.001) during the pegboard work, while no significant change was found for REF.

During the stress task, both VAS and RPE increased from 35.8 ± 27.5 to 39.4 ± 28.5 mm for VAS and from 3.2 ± 2.1 to 4.1 ± 2.7 points for RPE. Following the intervention, no significant changes were seen in neither VAS nor RPE for any of the groups.

Discussion

The novel finding of this study is the differential adaptive responses of contrasting physical exercise interventions on chronic muscle pain at rest and during repetitive work tasks. While GFT decreased pain development during repetitive work tasks, likely due to improved oxygenation of the painful muscles, SST lowered the overall level of pain both during rest and work, potentially due to a general lowered relative work load as evidenced by a lowered relative EMG in the standardized pegboard task.

The intervention study showed that 10 weeks of GFT improved oxygenation of chronically painful trapezius muscles during repetitive work tasks. Increased O2Hb and THb during the pegboard work indicate increased blood flow to the trapezius muscle similar to the response in healthy controls during such work tasks (Sjøgaard et al. 2010). Since MAP and EMG were unchanged this cannot be explained by increased perfusion pressure or a change in relative muscle load (relative EMG) during the pegboard task in response to GFT. In an earlier paper, we have reported a mean increase of 21% in aerobic fitness as response to the GFT intervention (Andersen et al. 2008). Therefore, an increased total blood volume potentially could explain the improved oxygenation of the trapezius muscle during the pegboard work. An alternative explanation is functional vascular adaptations in the non exercised muscles due to the training with large muscle groups such as the GFT in the present study. This could be indicated from the increase in blood flow in the relaxed trapezius during leg-bicycling shown in our recent study (Andersen et al. 2010). Also earlier studies support this having shown vascular adaptations such as increased forearm blood flow, blood viscosity, and release of nitric oxide in response to 4 weeks of leg-bicycle training at 65–70% VO2max (Kingwell et al. 1997; Silber et al. 1991).

After 10 weeks of SST, there was no change in THB during the pegboard task but a smaller change in HHb, and a tendency to an increased O2Hb. Thus, there was no change in blood flow and the results may rather reflect the lower relative workload in this group.

The rate of pain development during the pegboard task changed for GFT in terms of a 43% decrease in VAS slope. This improved resistance to pain development could have important practical relevance during low-force repetitive work tasks at the workplace. Further, even small reductions in pain and the increased level of aerobic fitness found in response to GFT may motivate persons with severe pain to overcome barriers to exercise.

In response to the SST intervention, a decrease in overall pain during the pegboard work task as well as a decrease of 52% in resting pain was observed. This is in line with earlier results from the same study showing a 79% decrease in worst pain based on pain-diary registrations (Andersen et al. 2008). However, the rate of pain development during the pegboard work did not change significantly in response to SST, likely due to the fact that the overall pain level was already markedly lowered. As recently reported in another paper from this study, both muscle thickness and shoulder elevation strength was increased in SST (Nielsen et al. 2010), and may explain the lowered relative workload of the trapezius muscle—as evidenced by a lowered relative EMG—during the pegboard task. Together these findings point towards differential adaptive mechanisms of pain reduction in response to GFT and SST.

EMG and MMG did not show signs of fatigue development during the 40-min pegboard work, even though fatigue development was expected compared with a previous study on a pegboard task where lighter weights were used (Rosendal et al. 2004a). In spite of decrease in relative workload (EMGRMS) during the pegboard task, no change was found in MMGRMS. MMG reflects the mechanical response in the muscle; since the absolute workload during the pegboard work was the same before and after the intervention, no changes were expected in MMGRMS.

In contrast to the pegboard task, the baseline results from the stress task were an increase in O2Hb and THb and a decrease in HHb for both myalgic and healthy subjects (Sjøgaard et al. 2010). This surprising result was not affected by the intervention. The acute increase in MAP with the stress task may have increased blood flow and thereby increased the blood volume in the trapezius muscle explaining the increase in oxygenation. Oxygen tension above resting level may have a deleterious effect on tissue structures due to its potential of increased formation of free radicals that may provoke lipolysis of membrane structures. Thus, over prolonged periods of time maintenance of homeostasis is crucial and neither reduced nor elevated levels of oxygenation may be beneficial although novel aspects on the role of free radicals as key regulators of muscle function has recently been presented (Jackson 2008).

A limitation of the present study is the initial dropout of participants in REF (n = 8), which made this group much smaller than the other intervention groups. In addition, a general concern is that the study may not have sufficient power to be fully conclusive on all variables.

In conclusion, as a short-term effect the study demonstrates differential adaptive mechanisms of two contrasting physical exercise interventions on chronic muscle pain during both repetitive work tasks and at rest. The GFT intervention performed as leg-bicycling decreased pain development in the trapezius muscle during repetitive work tasks. This may be due to the corresponding improved oxygenation of the painful muscles also demonstrated in this study. SST lowered the overall level of pain both during work and rest, possibly due to the lowered relative exposure as evidenced by a lowered relative EMG.

References

Ahlgren C, Waling K, Kadi F, Djupsjobacka M, Thornell LE, Sundelin G (2001) Effects on physical performance and pain from three dynamic training programs for women with work-related trapezius myalgia. J Rehabil Med 33:162–169

Andersen LL, Kjaer M, Søgaard K, Hansen L, Kryger A, Sjøgaard G (2008) Effect of two contrasting types of physical exercises on chronic neck muscle pain. Arthritis Rheum 59:84–91

Andersen LL, Andersen JL, Suetta C, Kjaer M, Sogaard K, Sjogaard G (2009) Effect of contrasting physical exercise interventions on rapid force capacity of chronically painful muscles. J Appl Physiol 107:1413–1419

Andersen LL, Blangsted AK, Nielsen PK, Hansen L, Vedsted P, Sjøgaard G, Søgaard K (2010) Effect of cycling on oxygenation of relaxed neck/shoulder muscles in women with and without chronic pain. Eur J Appl Physiol 110:389–394

Belardinelli R, Barstow TJ, Porszasz J, Wasserman K (1995) Changes in skeletal muscle oxygenation during incremental exercise measured with near infrared spectroscopy. Eur J Appl Physiol 70:487–492

Borg GAV (1982) Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med Sci Sports Exerc 14:377–381

Chance B, Dait MT, Zhang C, Hamaoka T, Hagerman F (1992) Recovery from exercise-induced desaturation in the quadriceps muscles of elite competitive rowers. Am J Physiol 262:C766–C775

DeSouza CA, Shapiro LF, Clevenger CM, Dinenno FA, Monahan KD, Tanaka H, Seals DR (2000) Regular aerobic exercise prevents and restores age-related declines in endothelium-dependent vasodilation in healthy men. Circulation 102:1351–1357

Frankenhaeuser M, Johansson G (1976) Task demand as reflected in catecholamine excretion and heart rate. J Human Stress 2:15–23

Jackson MJ (2008) Free radicals generated by contracting muscle: by-products of metabolism or key regulators of muscle function? Free Radic Biol Med 44:132–141

Jensen C, Vasseljen O, Westgaard RH (1993) The influence of electrode position on bipolar surface electromyogram recordings of the upper trapezius muscle. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 67:266–273

Juul-Kristensen B, Kadefors R, Hansen K, Bystrom P, Sandsjo L, Sjogaard G (2006) Clinical signs and physical function in neck and upper extremities among elderly female computer users: the NEW study. Eur J Appl Physiol 96:136–145

Kadi F, Waling K, Ahlgren C, Sundelin G, Holmner S, Butler-Browne GS, Thornell LE (1998) Pathological mechanisms implicated in localized female trapezius myalgia. Pain 78:191–196

Kingwell BA, Sherrard B, Jennings GL, Dart AM (1997) Four weeks of cycle training increases basal production of nitric oxide from the forearm. Am J Physiol 272:H1070–H1077

Larsson B, Bjork J, Henriksson KG, Gerdle B, Lindman R (2000) The prevalences of cytochrome c oxidase negative and superpositive fibres and ragged-red fibres in the trapezius muscle of female cleaners with and without myalgia and of female healthy controls. Pain 84:379–387

Larsson B, Bjork J, Kadi F, Lindman R, Gerdle B (2004) Blood supply and oxidative metabolism in muscle biopsies of female cleaners with and without myalgia. Clin J Pain 20:440–446

Larsson B, Sogaard K, Rosendal L (2007) Work related neck-shoulder pain: a review on magnitude, risk factors, biochemical characteristics, clinical picture and preventive interventions. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 21:447–463

Mackey AL, Andersen LL, Frandsen U, Suetta C, Sjogaard G (2010). Distribution of myogenic progenitor cells and myonuclei is altered in women with vs. those without chronically painful trapezius muscle. J Appl Physiol 109(6):1920–1929

McAllister RM (1998) Adaptations in control of blood flow with training: splanchnic and renal blood flows. Med Sci Sports Exerc 30:375–381

Nielsen PK, Andersen LL, Olsen HB, Rosendal L, Sjøgaard G, Søgaard K (2010) Effect of physical training on pain sensitivity and trapezius muscle morphology. Muscle Nerve 41:836–844

Ohlsson K, Attewell RG, Johnsson B, Ahlm A, Skerfving S (1994) An assessment of neck and upper extremity disorders by questionnaire and clinical examination. Ergonomics 37:891–897

Perko MJ, Nielsen HB, Skak C, Clemmesen JO, Schroeder TV, Secher NH (1998) Mesenteric, coeliac and splanchnic blood flow in humans during exercise. J Physiol 513(Pt 3):907–913

Rosendal L, Blangsted AK, Kristiansen J, Sogaard K, Langberg H, Sjogaard G, Kjaer M (2004a) Interstitial muscle lactate, pyruvate and potassium dynamics in the trapezius muscle during repetitive low-force arm movements, measured with microdialysis. Acta Physiol Scand 182:379–388

Rosendal L, Larsson B, Kristiansen J, Peolsson M, Søgaard K, Kjaer M, Sørensen J, Gerdle B (2004b) Increase in muscle nociceptive substances and anaerobic metabolism in patients with trapezius myalgia: microdialysis in rest and during exercise. Pain 2004:324–334

Silber D, McLaughlin D, Sinoway L (1991) Leg exercise conditioning increases peak forearm blood flow. J Appl Physiol 71:1568–1573

Sjøgaard G, Jensen BR, Hargens AR, Søgaard K (2004) Intramuscular pressure and EMG relate during static contractions but dissociate with movement and fatigue. J Appl Physiol 96:1522–1529

Sjøgaard G, Rosendal L, Kristiansen J, Blangsted AK, Skotte J, Larsson B, Gerdle B, Saltin B, Søgaard K (2010) Muscle oxygenation and glycolysis in females with trapezius myalgia during stress and repetitive work using microdialysis and NIRS. Eur J Appl Physiol 108:657–669

Strom V, Knardahl S, Stanghelle JK, Roe C (2009) Pain induced by a single simulated office-work session: time course and association with muscle blood flux and muscle activity. Eur J Pain 13:843–852

Tanaka H, Shimizu S, Ohmori F, Muraoka Y, Kumagai M, Yoshizawa M, Kagaya A (2006) Increases in blood flow and shear stress to nonworking limbs during incremental exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 38:81–85

Ylinen J, Takala EP, Nykanen M, Hakkinen A, Malkia E, Pohjolainen T, Karppi SL, Kautiainen H, Airaksinen O (2003) Active neck muscle training in the treatment of chronic neck pain in women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 289:2509–2516

Acknowledgments

Henrik Baare Olsen and Jesper Kristiansen are acknowledged for their contribution to data and statistical analyses. This study was supported by grants from the Danish Medical Research Council 22-03-0264 and the Danish Rheumatism Association 233-1149-02.02.04.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by Fausto Baldissera.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Søgaard, K., Blangsted, A.K., Nielsen, P.K. et al. Changed activation, oxygenation, and pain response of chronically painful muscles to repetitive work after training interventions: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Appl Physiol 112, 173–181 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-011-1964-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-011-1964-6