Abstract

Background

Our previous studies have shown that in standard automated perimetry (SAP) undersampling occurs if sensitivity varies across a visual field faster than the Nyquist rate (Nq) for the standard sampling interval of 6°. This undersampling was shown to be a major source of test–retest variability. This study first tests some of the assumptions of the undersampling idea, and then determines the relative contributions to test–retest variability of normal eye movements and undersampling.

Methods

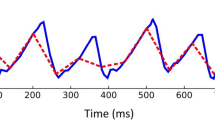

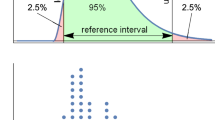

In all models fixational jitter was at normal levels. The first part investigates the effects of the jitter on the Fourier spectra of fields, and stimulus size effects. In the second part fields are smoothed in six gradations up to and beyond the point where no undersampling could occur. The spatial smoothing gradations covered nil to < Nq/4. For each smoothing level the resulting retest variability was determined for each of 11 bands of scotoma depth (0 to −28.5 dB).

Results

As is commonly reported, and as undersampling predicts, retest variability was largest for deeper scotoma depths. When smoothing suppressed all undersampling effects, the inter-quartile range of the residual retest variability averaged only 2.3 ± 0.33 dB, much smaller than for unsmoothed fields (p < 0.003). For the five deepest scotoma depth bands (range, −16.5 to −28.5 dB) retest variability was smaller by 6.0 ± 0.5 dB (p < 0.0005).

Conclusions

Retest variability appears in large part to be driven by undersampling. In real fields, the remaining variance would come from fixation errors and physiological sources.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Artes P, Iwase A, Ohno Y, Kitazawa Y, Chauhan B (2002) Properties of perimetric threshold estimates from full threshold, SITA standard, and SITA fast strategies. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci 43:2654–2659

Wall M, Woodward KR, Doyle CK, Artes PH (2009) Repeatability of automated perimetry: a comparison between standard automated perimetry with stimulus size III and V, matrix, and motion perimetry. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 50(2):974–979

Heijl A, Lindgren A, Lindgren G (1989) Test–retest variability in glaucomatous visual fields. Am J Ophthalmol 108:130–135

Blumenthal EZ, Sample PA, Zangwill L, Lee AC, Kono Y, Weinreb RN (2000) Comparison of long-term variability for standard and short-wavelength automated perimetry in stable glaucoma patients. Am J Ophthalmol 129:309–313

Kwon YH, Park HJ, Jap A, Ugurlu S, Caprioli J (1998) Test–retest variability of blue-on-yellow perimetry is greater than white-on-white perimetry in normal subjects. Am J Ophthalmol 126(1):29–36

Piltz JR, Starita RJ (1990) Test–retest variability in glaucomatous visual fields. Am J Ophthalmol 109:109–111

Chauhan BC, Johnson CA (1999) Test–retest variability of frequency-doubling perimetry and conventional perimetry in glaucoma patients and normal subjects. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 40(3):648–656

Artes PH, Hutchison DM, Nicolela MT, LeBlanc RP, Chauhan BC (2005) Threshold and variability properties of matrix frequency-doubling technology and standard automated perimetry in glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 46(7):2451–2457

Chauhan BC, Garway-Heath DF, Goni FJ, Rossetti L, Bengtsson B, Viswanathan AC, Heijl A (2008) Practical recommendations for measuring rates of visual field change in glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol 92(4):569–573

Henson DB, Chaudry S, Artes PH, Faragher EB, Ansons A (2000) Response variability in the visual field: comparison of optic neuritis, glaucoma, ocular hypertension, and normal eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 41(2):417–421

Maddess T (2011) The influence of sampling errors on test–retest variability in perimetry. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 52:1014–1022

Bracewell RN (1986) Chapter 10. Sampling and series. In: The Fourier transform and its applications. 2nd ed. 1978, revised 1986. McGraw-Hill, New York, pp 189–218

Giesler WS, Hamilton DB (1986) Sampling-theory analysis of spatial vision. J Opt Soc Am A3:62–70

Wall M, Woodward KR, Doyle CK, Zamba GJ, Johnson CA (2009) The effect of stimulus size on repeatability in glaucoma using Goldmann sizes III, V, and VI. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 50:2239

Maddess T, Hemmi JM, James AC (1998) Evidence for spatial aliasing effects in the Y-like cells of the magnocellular visual pathway. Vis Res 38(12):1843–1859

Airaksinen HA (1983) Visual field and retinal fibre layer in early glaucoma after optic disc haemorrhage. Acta Ophthalmol 61:186–194

Sturmer J (1985) What do glaucomatous visual fields really look like in fine-grid computerized profile perimetry? Dev Ophthalmol 12:1–47

Fellman RL, Lynn JR, Starita RJ, Swanson WH (1989) Clinical importance of spatial summation in glaucoma. In: Heijl A, Swanson WH (eds) Perimetry update 1988:1989. Kugler & Ghedini, Berkeley, pp 313–324

Westcott MC, McNaught AI, Crabb DP, Fitzke FW, Hitchings RA (1997) High spatial resolution automated perimetry in glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol 81(6):452–459

Haefliger IO, Flammer J (1989) Increase of the short-term fluctuation of the differential light threshold around a physiologic scotoma. Am J Ophthalmol 107(4):417–420

Haefliger IO, Flammer J (1991) Fluctuation of the differential light threshold at the border of absolute scotomas. Comparison between glaucomatous visual field defects and blind spots. Ophthalmol 98:1529–1532

Wyatt HJ, Dul MW, Swanson WH (2007) Variability of visual field measurements is correlated with the gradient of visual sensitivity. Vis Res 47(7):925–936

Yellott JI (1983) Spectral consequences of photorecptor sampling in the rhesus retina. Science 221:382–385

Rohrschneider K, Becker M, Schumacher N, Fendrich T, Volcker HE (1998) Normal values for fundus perimetry with the scanning laser ophthalmoscope. Am J Ophthalmol 126(1):52–58

Springer C, Bultmann S, Volcker HE, Rohrschneider K (2005) Fundus perimetry with the micro perimeter 1 in normal individuals: comparison with conventional threshold perimetry. Ophthalmology 112(5):848–854

Maddess T, Severt W, Stange G (2001) Comparison of three tests using the frequency doubling illusion to diagnose glaucoma. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 29:359–367

Maddess T, Goldberg I, Wine S, Dobinson J, Welsh AH, James AC (1999) Testing for glaucoma with the spatial frequency doubling illusion. Vis Res 39:4258–4273

Hot A, Dul MW, Swanson WH (2008) Development and evaluation of a contrast sensitivity perimetry test for patients with glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 49(7):3049–3057

Gonzalez-Hernandez M, Garcia-Feijoo J, Mendez MS, de la Rosa MG (2004) Combined spatial, contrast, and temporal functions perimetry in mild glaucoma and ocular hypertension. Eur J Ophthalmol 14(6):514–522

Keltgen KM, Swanson WH (2012) Estimation of spatial scale across the visual field using sinusoidal stimuli. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 53:633–639

Spry PG, Hussin HM, Sparrow JM (2005) Clinical evaluation of frequency doubling technology perimetry using the Humphrey Matrix 24–2 threshold strategy. Br J Ophthalmol 89(8):1031–1035

Wall M, Woodward KR, Doyle CK, Zamba G (2010) The effective dynamic ranges of standard automated perimetry sizes III and V and motion and matrix perimetry. Arch Ophthalmol 128(5):570–576

James AC, Kolic M, Bedford SM, Maddess T (2012) Stimulus parameters for multifocal pupillographic objective perimetry. J Glaucoma 21:571–578

Sabeti F, Maddess T, Essex RW, James AC (2013) Dichoptic multifocal pupillography identifies retinal dysfunction in early AMD. Graef's Arch Ophthalmol 126:125–136

Bell A, James AC, Kolic M, Essex RW, Maddess T (2010) Dichoptic multifocal pupillography reveals afferent visual field defects in early type 2 diabetes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 51:602–608

Weber J, Dobek K (1986) What is the most suitable grid for computer perimetry in glaucoma patients? Ophthalmologica 192(2):88–96

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Australian Research Council through the ARC Centre of Excellence in Vision Science (CE0561903).

Conflict of interest

The author receives royalties from Carl Zeiss Meditec on sales of the FDT/Matrix perimeters based on a patent held for those devices, although this is not directly related to the present study. The author also has patents, and patent applications, on related methods for multifocal pupillographic objective perimetry (mfPOP). Those patents are under license to Seeing Machines Ltd. One of those applications, WO2009059380A1, includes among other things, the principle of smooth-sided and overlapping perimetry stimuli, which are mentioned in this study. The mfPOP patents and applications are not currently generating any income for the author but may do so in future.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Maddess, T. Modeling the relative influence of fixation and sampling errors on retest variability in perimetry. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 252, 1611–1619 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-014-2751-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-014-2751-y