Abstract

Background

Studies on glaucoma therapy were analyzed with regard to study design, diagnostic parameters and success criteria.

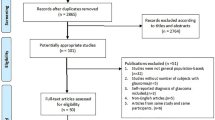

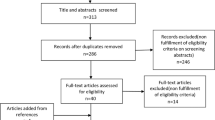

Materials and methods

In 11 frequently read peer-reviewed periodicals, 101 studies published between 1996 and 1999 were chosen according to specific criteria. Design parameters, diagnostic measures and success criteria were investigated.

Results

Thirty-seven studies were retrospective and 64 prospective. Twenty-five studies were multicenter studies. Thirty-seven studies dealt with drug therapy, 12 with laser therapy, and 52 with surgical therapy. The study duration in 51% of the studies (n=52) was up to 1 year, in 28% (n=28) from 1 to 2 years, in 17% (n=17) over 2 years, and in 5% (n=5) in excess of 4 years. Four studies gave insufficient data. Forty-one studies recruited less than 50 patients and 57 studies recruited less than 75 patients. Thirty-four studies included more than 100 patients and 11 studies more than 250 patients. Sixty-one studies included race as a parameter. All 101 studies measured intraocular pressure (IOP). Forty-five studies explicitly described the method of tonometry. Thirteen studies measured a diurnal IOP. Forty-one studies examined the visual field, of which 30 named the method of perimetry. Only 28 studies examined the optic disc morphology. They all employed ophthalmoscopy, and two additionally employed optic disc photography. Sixty-three studies explicitly defined success criteria, establishing 95 different definitions: 74 definitions (78%) used a specified value for IOP as a success criterion. Out of the 70 definitions that gave an absolute value for IOP, 12 definitions (17%) used IOP values between 14 and 16 mmHg as the upper limit, 4 definitions (6%) used IOP values between 17 and 19 mmHg, and 54 definitions (77%) used IOP values between 20 and 22 mmHg. Out of the 26 definitions that specified a percentage IOP reduction, it was judged to be a success when the IOP was lowered by 20% or more from the starting value in ten definitions (38%), by 25% or more in three definitions (12%), and by 30% or more in 13 definitions (50%).

Conclusions

Examples of prestigious studies show the necessity of observation periods of several years and demonstrate the need for a high number of participants, necessitating the cooperation of many study centers. Beside a more precise characterization of the patient collectives, clinical studies should always specify the measurement method clearly. Investigating a diurnal IOP profile to recognize changes in IOP and IOP peaks, as well as the routine determination of central corneal thickness, would be desirable. New diagnostic techniques for improved assessment of the functional and morphologic damage will gain in relevance in the future. The lack of a common definition of success reveals the complexity of the disease. However, an IOP reduction based on the degree of damage and ascertaining the target pressure seems sensible.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

AGIS Investigators (1994) The Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study (AGIS). 1. Study design and methods, and baseline characteristics of study patients. Control Clin Trials 15:299–325

AGIS Investigators (1998) The Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study (AGIS). 4. Comparison of treatment outcomes within race. Seven-year results. Ophthalmology 105:1146–1164

AGIS Investigators (2000) The Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study (AGIS). 7. The relationship between control of intraocular pressure and visual field deterioration. Am J Ophthalmol 130:429–440

AGIS Investigators (2001) The Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study (AGIS). 9. Comparison of glaucoma outcomes in black and white patients within treatment groups. Am J Ophthalmol 132:311–320

American Academy of Ophthalmology (1996) Preferred practice pattern: primary open-angle glaucoma. American Academy of Ophthalmology, San Francisco

Anderson DR (1989) Glaucoma: the damage caused by pressure. XLVI Edward Jackson memorial lecture. Am J Ophthalmol 108:485–495

Anderson DR (1992) Automated static perimetry. Mosby-Year Book, St Louis

Bathija R, Gupta N, Zangwill L, Weinreb RN (1998) Changing definition of glaucoma. J Glaucoma 7:165–169

Broadway DC, Grierson I, Hitchings RA (1994) Racial differences in the results of glaucoma filtration surgery: are racial differences in the conjunctival cell profile important? Br J Ophthalmol 78:466–475

Brusini P, Miani F, Tosoni C (2000) Corneal thickness in glaucoma: an important parameter? Acta Opthalmol Scand 78(Suppl):S41–S42

Collaborative Normal Tension Glaucoma Study Group (1998) Comparison of glaucomatous progression between untreated patients with normal-tension glaucoma and patients with therapeutically reduced intraocular pressure. Am J Ophthalmol 126:487–497

Coulehan JL, Helzlsouer KJ, Rogers KD, Brown SI (1980) Racial differences in intraocular tension and glaucoma surgery. Am J Epidemiol 111:759–768

David R, Zangwill L, Briscoe D, Dagan M, Yagev R, Yassur Y (1992) Diurnal intraocular pressure variations: an analysis of 690 diurnal curves. Br J Ophthalmol 76:280–283

Drance SM (1999) The collaborative normal-tension glaucoma study and some of its lessons. Can J Ophthalmol 34:1–6

Drance SM, Anderson DR, Schulzer M (2001) Risk factors for progression of visual field abnormalities in normal-tension glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol 131:699–708

European Glaucoma Society (2003) Terminology and guidelines for glaucoma, 2nd edn. Dogma, Savona, Italy, ISBN 88-87434-13-1

Fluorouracil Filtering Surgery Study Group (1989) One-year follow up. The Fluorouracil Filtering Surgery Study. Am J Ophthalmol 108:625–635

Fluorouracil Filtering Surgery Study Group (1996) Five-year follow-up of the Fluorouracil Filtering Surgery Study. Am J Ophthalmol 121:349–366

Glaucoma Laser Trial Research Group (1991) The Glaucoma Laser Trial (GLT). 3. Design and methods. Glaucoma Laser Trial Research Group. Control Clin Trials 12:504–524

Glaucoma Laser Trial Research Group (1995) The Glaucoma Laser Trial (GLT) and Glaucoma Laser Trial Followup Study. 7. Results. Am J Ophthalmol 120:718–731

Gloor B, Meier Gibbons F (1996) Prinzipien der Effizienzkontrolle der Glaukomtherapie. Ophthalmologe 93:510–519

Gordon MO, Kass MA (1999) The ocular hypertension treatment study: design and baseline description of the participants. Arch Ophthalmol 117:573–583

Grant WM, Burke JF Jr (1982) Why do some people go blind from glaucoma? Ophthalmology 89:991–998

Hrynchak P, Simpson T (2000) Optical coherence tomography: an introduction to the technique and its use. Optom Vis Sci 77:347–356

Johnson CA (2002) Recent developments in automated perimetry in glaucoma diagnosis and management. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 13:77–84

Kass MA, Heuer DK, Higginbotham EJ, Johnson CA, Keltner JL, Miller JP, Parrisch RK II, Wilson MR, Gordon MO (2002) The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study: a randomized trial determines that topical ocular hypotensive medication delays or prevents the onset of primary open-angle glaucoma. Surv Ophthalmol 120:701–713

Khaw PT, Papadopoulos M (2001) A year is a short time in glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol 85:637–638

Konstas AG, Mantziris DA, Stewart WC (1997) Diurnal intraocular pressure in untreated exfoliation and primary open-angle glaucoma. Surv Ophthalmol 115:182–185

Krummenauer F, Dick B, Schwenn O, Pfeiffer N (2002) The determination of sample size in controlled clinical trials in ophthalmology. Br J Ophthalmol 86:946–947

Leske MC, Heijl A, Hyman L, Bengtsson B (1999) Early manifest glaucoma trial: design and baseline data. Ophthalmology 106:2144–2153

Lichter PR, Musch DC, Gillespie BW, Guire KE, Janz NK, Wren PA, Mills RP (2001) Interim clinical outcomes in the Collaborative Initial Glaucoma Treatment Study (CIGTS) comparing initial treatment randomized to medications or surgery. Ophthalmology 108:1943–1953

Liu JH, Kripke DF, Twa MD, Hoffman RE, Mansberger SL, Rex KM, Girkin CA, Weinreb RN (1999) Twenty-four-hour pattern of intraocular pressure in the aging population. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 40:2912–2917

Martin LM, Lindblom B, Gedda UK (2000) Concordance between results of optic disc tomography and high-pass resolution perimetry in glaucoma. J Glaucoma 9:28–33

Musch DC, Lichter PR, Guire KE, Standardi CL (1999) The Collaborative Initial Glaucoma Treatment Study (CIGTS): study design, methods, and baseline characteristics of enrolled patients. Ophthalmology 106:653–662

Pardhan S, Mahomed I (2002) The clinical characteristics of Asian and Caucasian patients on Bradford’s Low Vision Register. Eye 16:572–576

Pfeiffer N (2001) Glaukom. Grundlagen–Diagnostik–Therapie–Compliance. Thieme, Stuttgart

Quigley HA, Vitale S (1997) Models of open-angle glaucoma prevalence and incidence in the United States. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 38:83–91

Quigley HA, West SK, Rodriguez J, Munoz B, Klein R, Snyder R (2001) The prevalence of glaucoma in a population-based study of Hispanic subjects: proyecto VER. Surv Ophthalmol 119:1819–1826

Sacca SC, Rolando M, Marletta A, Macri A, Cerqueti P, Ciurlo G (1998) Fluctuations of intraocular pressure during the day in open-angle glaucoma, normal-tension glaucoma and normal subjects. Ophthalmologica 212:115–119

Sample PA, Ahn DS, Lee PC, Weinreb RN (1992) High-pass resolution perimetry in eyes with ocular hypertension and primary open-angle glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol 113:309–316

Schulzer M (1994) Errors in the diagnosis of visual field progression in normal-tension glaucoma. Ophthalmology 101:1589–1594

Smith SD, Katz J, Quigley HA (1996) Analysis of progressive change in automated visual fields in glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 37:1419–1428

Sommer A, Tielsch JM, Katz J, Quigley HA, Gottsch JD, Javitt J, Singh K (1991) Relationship between intraocular pressure and primary open angle glaucoma among white and black Americans. The Baltimore Eye Survey. Surv Ophthalmol 109:1090–1095

Spaeth GL (1999) Defining glaucoma, defining disease: the 1998 Dohlman Lecture. Int Ophthalmol Clin 39:1–14

Ventura AC, Bohnke M, Mojon DS (2001) Central corneal thickness measurements in patients with normal tension glaucoma, primary open angle glaucoma, pseudoexfoliation glaucoma, or ocular hypertension. Br J Ophthalmol 85:792–795

Weinreb RN (1993) Laser scanning tomography to diagnose and monitor glaucoma. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 4:3–6

Whitacre MM, Stein R (1993) Sources of error with use of Goldmann-type tonometers. Surv Ophthalmol 38:1–30

Wilson R, Richardson TM, Hertzmark E, Grant WM (1985) Race as a risk factor for progressive glaucomatous damage. Ann Ophthalmol 17:653–659

Zangwill L, Shakiba S, Caprioli J, Weinreb RN (1995) Agreement between clinicians and a confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscope in estimating cup/disk ratios. Am J Ophthalmol 119:415–421

Zulauf M, Caprioli J (1992) What constitutes progression of glaucomatous visual field defects? Semin Ophthalmol 7:130–146

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schwenn, O., Yun, S.H., Troost, A. et al. Glaucoma studies from 1996 to 1999 in peer-reviewed journals. Graefe's Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 243, 629–636 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-004-1105-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-004-1105-6