Abstract

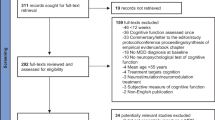

Many individuals with major depression disorder (MDD) who achieve remission of depressive symptoms, do not perceive themselves as fully recovered. This study explores whether clinical remission is related to functional remission and to patient’s perception of recovery, as well as, which factors are associated with their functional and subjective remission. 148 patients with MDD in partial clinical remission were included. Demographics and clinical variables were collected through semi-structured interviews. Objective cognition was evaluated through a neuropsychological battery and subjective cognition through a specific questionnaire. The patient’s psychosocial functioning and the perception of their remission were also assessed. Apart from descriptive analysis, Pearson correlations and backward stepwise regression models explored the relationship between demographic, clinical, and cognitive factors with patients’ functional and self-perceived remission. From the whole sample, 57 patients (38.5%) were considered to achieve full clinical remission, 38 patients (25.7%) showed functional remission, and 55 patients (37.2%) perceived themselves as remitted. Depressive symptoms and objective and subjective executive function were the factors associated with psychosocial functioning. Besides, depressive symptoms, objective and subjective attention, and subjective executive function were the significant explanatory variables for self-perception of remission. The concept of full recovery from an episode of MDD should not only include the clinician’s perspective but also the patient’s psychosocial functioning along with their self-perceived remission. As residual depressive symptoms and cognition (objective and subjective) are factors with great contribution to a full recovery, clinicians should specifically address them when choosing therapeutic strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data and code availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

IsHak WW, James D, Mirocha J et al (2016) Patient-reported functioning in major depressive disorder. Ther Adv Chronic Dis 7:160–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/2040622316639769

De Vries G, Koeter MWJ, Nieuwenhuijsen K et al (2015) Predictors of impaired work functioning in employees with major depression in remission. J Affect Disord 185:180–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.07.013

Rush AJ, South CC, Jha MK et al (2019) Toward a very brief quality of life enjoyment and satisfaction questionnaire. J Affect Disord 242:87–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.08.052

Sheehan DV, Nakagome K, Asami Y et al (2017) Restoring function in major depressive disorder: a systematic review. J Affect Disord 215:299–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.02.029

McGlinchey JB, Zimmerman M, A. Posternak M, et al (2006) The impact of gender, age and depressed state on patients’ perspectives of remission. J Affect Disord 95:79–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2006.04.021

Kan K, Jörg F, Buskens E et al (2020) Patients’ and clinicians’ perspectives on relevant treatment outcomes in depression: qualitative study. BJPsych Open 6:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2020.27

Zimmerman M, Martinez J, Attiullah N et al (2012) Why do some depressed outpatients who are not in remission according to the Hamilton depression rating scale nonetheless consider themselves to be in remission? Depress Anxiety 29:891–895. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.21987

Zimmerman M, Martinez J, Attiullah N et al (2012) Symptom differences between depressed outpatients who are in remission according to the Hamilton depression rating scale who do and do not consider themselves to be in remission. J Affect Disord 142:77–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2012.03.044

Demyttenaere K, Donneau AF, Albert A et al (2015) What is important in being cured from depression? Discordance between physicians and patients. J Affect Disord 174:390–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.12.004

Stotland NL (2012) Recovery from depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am 35:37–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2011.11.007

Solhaug HI, Romuld EB, Romild U, Stordal E (2012) Increased prevalence of depression in cohorts of the elderly: an 11-year follow-up in the general population-the HUNT study. Int Psychogeriatrics 24:151–158. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610211001141

McIntyre RS, Cha DS, Soczynska JK et al (2013) Cognitive deficits and functional outcomes in major depressive disorder: determinants, substrates, and treatment interventions. Depress Anxiety 30:515–527. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22063

Evans VC, Iverson GL, Yatham LN, Lam RW (2014) The relationship between neurocognitive and psychosocial functioning in major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 75:1359–1370. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.13r08939

Knight MJ, Air T, Baune BT (2018) The role of cognitive impairment in psychosocial functioning in remitted depression. J Affect Disord 235:129–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.04.051

Christensen MC, Wong CMJ, Baune BT (2020) Symptoms of major depressive disorder and their impact on psychosocial functioning in the different phases of the disease: do the perspectives of patients and healthcare providers differ? Front Psychiatry 11:1–9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00280

Kim SE, Kim H-N, Cho J et al (2016) Direct and Indirect Effects of five factor personality and gender on depressive symptoms mediated by perceived stress. PLoS One. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0154140

Chokka P, Bougie J, Proulx J et al (2019) Long-term functioning outcomes are predicted by cognitive symptoms in working patients with major depressive disorder treated with vortioxetine: results from the AtWoRC study. CNS Spectr 24:616–627. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852919000786

Serra-Blasco M, Torres IJ, Vicent-Gil M et al (2019) Discrepancy between objective and subjective cognition in major depressive disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 29:46–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2018.11.1104

Vicent-Gil M, Portella MJ, Serra-Blasco M et al (2021) Dealing with heterogeneity of cognitive dysfunction in acute depression: a clustering approach. Psychol Med 51:2886–2894. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720001567

López-Solà C, Subirà M, Serra-Blasco M et al (2020) Is cognitive dysfunction involved in difficult-to-treat depression? Characterizing resistance from a cognitive perspective. Eur Psychiatry 63:e74. https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.65

Sackeim HA (2001) The definition and meaning of treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry 62:10–17

Bobes J, Bulbena A, Luque A et al (2003) Evaluación psicométrica comparativa de las versiones en español de 6, 17 y 21 ítems de la escala de valoración de Hamilton para la evaluación de la depresión. Med Clin 120:693–700. https://doi.org/10.1157/13047695

Hamilton M (1960) A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 23:56–62. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56

Rock PL, Roiser JP, Riedel WJ, Blackwell AD (2014) Cognitive impairment in depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med 44:2029–2040. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291713002535

Wechsler D (2008) Weschler adult intelligence scale (WAIS-IV), 4th edn. Pearson, San Antonio

Tombaugh TN (2004) Trail making test A and B: normative data stratified by age and education. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 19:203–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0887-6177(03)00039-8

Rey A (1941) L’examen clinique en psychologie. Presses Universitaires de France, Paris

Casals-Coll M, Sánchez-Benavides G, Quintana M et al (2013) Estudios normativos españoles en población adulta joven (proyecto NEURONORMA jóvenes): Normas para los test de fluencia verbal. Neurologia 28:33–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nrl.2012.02.010

Pena-Casanova J, Quinones-Ubeda S, Gramunt-Fombuena N et al (2009) Spanish multicenter normative studies (NEURONORMA Project): norms for verbal fluency tests. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 24:395–411. https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/acp042

Heaton RK (1981) Wisconsin card sorting test manual. Psychological Assessment Resources, Odessa

Iverson GL, Lam RW (2013) Rapid screening for perceived cognitive impairment in major depressive disorder. Annu Clin Psychiatry 25:135–140

Strober LB, Binder A, Nikelshpur OM et al (2016) The perceived deficits questionnaire: perception, deficit, or distress? Int J MS Care 18:183–190. https://doi.org/10.7224/1537-2073.2015-028

Rosa AR, Sánchez-Moreno J, Martínez-Aran A et al (2007) Validity and reliability of the functioning assessment short test (FAST) in bipolar disorder. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Heal 3:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-0179-3-Received

Bonnín CM, Martínez-Arán A, Reinares M et al (2018) Thresholds for severity, remission and recovery using the functioning assessment short test (FAST) in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord 240:57–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.07.045

Zimmerman M, Martinez JH, Attiullah N et al (2013) A new type of scale for determining remission from depression: the remission from depression questionnaire. J Psychiatr Res 47:78–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.09.006

Lezak MD, Howieson DB, Loring DW et al (2004) Neuropsychological Assessment, 4th edn. Oxford University Press, New York

IsHak WW, Bonifay W, Collison K et al (2017) The recovery index: a novel approach to measuring recovery and predicting remission in major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord 208:369–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.08.081

Sarfati D, Stewart K, Cindy Woo B et al (2017) The effect of remission status on work functioning in employed patients treated for major depressive disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry 29:11–16

Saris IMJ, Aghajani M, van der Werff SJA et al (2017) Social functioning in patients with depressive and anxiety disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand 136:352–361. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12774

Habert J, Katzman MA, Oluboka OJ et al (2016) Functional recovery in major depressive disorder. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.15r01926

Kamenov K, Twomey C, Cabello M et al (2017) The efficacy of psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy and their combination on functioning and quality of life in depression: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med 47:414–425. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716002774

Montoya A, Lebrec J, Keane KM et al (2016) Broader conceptualization of remission assessed by the remission from depression questionnaire and its association with symptomatic remission: a prospective, multicenter, observational study. BMC Psychiatry 16:352. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-1067-3

Pérez V, Martínez-Navarro R, Pérez-Aranda A et al (2021) A multicenter, observational study of pain and functional impairment in individuals with major depressive disorder in partial remission: the DESIRE study. J Affect Disord 281:657–660

Uher R, Perlis RH, Placentino A et al (2012) Self-report and clinician-rated measures of depression severity: Can one replace the other? Depress Anxiety 29:1043–1049. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.21993

Xiao L, Feng L, Zhu X-Q et al (2018) Comparison of residual depressive symptoms and functional impairment between fully and partially remitted patients with major depressive disorder: a multicenter study. Psychiatry Res 261:547–553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.01.020

Paykel ES (2008) Partial remission, residual symptoms, and relapse in depression. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 10:431–437. https://doi.org/10.31887/dcns.2008.10.4/espaykel

Menza M, Marin H, Opper RS (2003) Residual symptoms in depression: can treatment be symptom-specific? J Clin Psychiatry 64:516–523. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v64n0504

Trujols J, Portella MJ, Iraurgi I et al (2013) Patient-reported outcome measures: are they patient-generated, patient-centred or patient-valued? J Ment Heal 22:555–562. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2012.734653

Trujols J, Portella MJ, Pérez V (2013) Toward a genuinely patient-centered metric of depression recovery: one step further. JAMA Psychiat 70:1375. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2187

Park M, Giap TTT, Lee M et al (2018) Patient- and family-centered care interventions for improving the quality of health care: a review of systematic reviews. Int J Nurs Stud 87:69–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.07.006

Rush AJ, Michael MD, Thase E (2018) Improving depression outcome by patient-centered medical management. Am J Psychiatry 175:1187–1198. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.18040398

de Nooij L, Harris MA, Adams MJ et al (2020) Cognitive functioning and lifetime major depressive disorder in UK Biobank. Eur Psychiatry 63:e28. https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.24

Snyder HR (2013) Major depressive disorder is associated with broad impairments on neuropsychological measures of executive function: a meta-analysis and review. Psychol bull 139:81–132. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028727

Letkiewicz AM, Miller GA, Crocker LD et al (2014) Executive function deficits in daily life prospectively predict increases in depressive symptoms. Cognit Ther Res 38:612–620. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-014-9629-5

Cambridge OR, Knight MJ, Mills N, Baune BT (2018) The clinical relationship between cognitive impairment and psychosocial functioning in major depressive disorder: a systematic review. Psychiatry Res 269:157–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.08.033

Yaroslavsky I, Allard ES, Sanchez-Lopez A (2019) Can’t look away: attention control deficits predict rumination, depression symptoms and depressive affect in daily life. J Affect Disord 245:1061–1069. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.036

Milanovic M, Holshausen K, Milev R, Bowie CR (2018) Functional competence in major depressive disorder: objective performance and subjective perceptions. J Affect Disord 234:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.02.094

Serra-Blasco M, Lam RW (2019) Clinical and functional characteristics of cognitive dysfunction in major depressive disorder. In: Harmer CJ, Baune BT (eds) Cognitive dimensions of major depressive disorder. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 45–58

Potvin S, Charbonneau G, Juster RP et al (2016) Self-evaluation and objective assessment of cognition in major depression and attention deficit disorder: Implications for clinical practice. Compr Psychiatry 70:53–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.06.004

Sumiyoshi T, Watanabe K, Noto S et al (2019) Relationship of cognitive impairment with depressive symptoms and psychosocial function in patients with major depressive disorder: cross–sectional analysis of baseline data from PERFORM-J. J Affect Disord 258:172–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.07.064

Zhang BH, Feng L, Feng Y et al (2020) The effect of cognitive impairment on the prognosis of major depressive disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis 208:683–688. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000001180

Wang G, Si TM, Li L et al (2019) Cognitive symptoms in major depressive disorder: associations with clinical and functional outcomes in a 6-month, non-interventional, prospective study in China. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 15:1723–1736. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S195505

Sawada K, Yoshida K, Ozawa C et al (2019) Impact of subjective vs. objective remission status on subjective cognitive impairments in depression. J Affect Disord 246:99–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.049

Saragoussi D, Christensen MC, Hammer-Helmich L et al (2018) Long-term follow-up on health-related quality of life in major depressive disorder: a 2-year European cohort study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 14:1339–1350. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S159276

Zajecka JM (2013) Residual symptoms and relapse. J Clin Psychiatry 74:9–13. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.12084su1c.02

Miskowiak KW, Ott CV, Petersen JZ, Kessing LV (2016) Systematic review of randomized controlled trials of candidate treatments for cognitive impairment in depression and methodological challenges in the field. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 26:1845–1867. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2016.09.641

Salagre E, Solé B, Tomioka Y et al (2017) Treatment of neurocognitive symptoms in unipolar depression: a systematic review and future perspectives. J Affect Disord 221:205–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.06.034

Vicent-Gil M, Raventós B, Marín-Martínez ED et al (2019) Testing the efficacy of INtegral Cognitive REMediation (INCREM) in major depressive disorder: study protocol for a randomized clinical trial. BMC Psychiatry 19:135. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2117-4

Listunova L, Kienzle J, Bartolovic M et al (2020) Cognitive remediation therapy for partially remitted unipolar depression: a single-blind randomized controlled trial. J Affect Disord 276:316–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.008

Hagen BI, Lau B, Joormann J et al (2020) Goal management training as a cognitive remediation intervention in depression: A randomized controlled trial. J Affect Disord 275:268–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.015

Ott CV, Vinberg M, Kessing LV, Miskowiak KW (2016) The effect of erythropoietin on cognition in affective disorders–associations with baseline deficits and change in subjective cognitive complaints. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 26:1264–1273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2016.05.009

Petersen JZ, Porter RJ, Miskowiak KW (2019) Clinical characteristics associated with the discrepancy between subjective and objective cognitive impairment in depression. J Affect Disord 246:763–774. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.105

Srisurapanont M, Suttajit S, Eurviriyanukul K, Varnado P (2017) Discrepancy between objective and subjective cognition in adults with major depressive disorder. Sci Rep 7:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-04353-w

Shields GS, Sazma MA, Yonelinas AP (2016) The effects of acute stress on core executive functions: a meta-analysis and comparison with cortisol. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 68:651–668. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.06.038

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients who participated in this study. We also thank the staff of the Department of Psychiatry of the Hospital Universitari Parc Taulí for their kind collaboration in patient recruitment.

Funding

This study was supported by Lundbeck España (Institutional ethical committee # 2015630).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Dr. Maria J Portella was funded until 2020 by the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación of the Spanish Government and by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III through a ‘Miguel Servet-II’ research contract (CPII16-0020), National Research Plan (Plan Estatal de I + D + I 2016-2019), co-financed by the ERDF and by CERCA Programme/Generalitat de Catalunya; she received funding from the Health Research and Innovation Strategic Plan (PERIS) SLT006/17/00177, and honoraria as CME speaker from Pfizer and Lundbeck within the last 3 years. Dr. Narcís Cardoner declares that he has received funding from the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, Instituto Carlos III and from Health Research and Innovation Strategic Plan (PERIS) 2016–2020. He has also received honoraria as consultant, advisor or CME speaker from Janssen, Lundbeck, Pfizer, Exeltis and MSD within the last 3 years. The rest of authors have nothing to disclose.

Ethical approval

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Consent to participate

All participants provided written informed consent.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

M., VG., M., SB., G., NV. et al. In pursuit of full recovery in major depressive disorder. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 273, 1095–1104 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-022-01487-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-022-01487-5