Abstract

Background and objectives

The Pro51Ser (P51S) COCH mutation is characterized by a late-onset bilateral sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) and progressive vestibular deterioration. The aim of this study was to carry out a systematic review of all reported hearing and vestibular function data in P51S COCH mutation carriers and its correlation with age.

Materials and methods

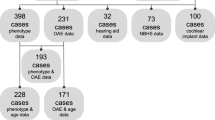

Scientific databases including Medline, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, ISI Web of Knowledge, and Web of Science were searched to accumulate information about hearing outcome and vestibular function. Eleven genotype–phenotype correlation studies of the P51S COCH variant were identified and analyzed.

Results

The SNHL starts at the age of 32.8 years. The Annual Threshold Deterioration is 3 decibel hearing loss (dB HL) per year (1–24 dB HL/year). Profound SNHL was observed at 76 years on average (60–84 years). 136 individual vestibular measurements were collected from 86 carriers. The onset of the vestibular dysfunction was estimated around 34 years (34–40 years), and vestibular deterioration rates were higher than those of the SNHL, with complete bilateral loss observed between 49 and 60 years.

Conclusion

Both audiometric and vestibular data were processed with much different methodologies and pre-symptomatic P51S carriers were systematically underrepresented. Further delineation of this correlation would benefit cross-sectional and longitudinal study involving all (pre-symptomatic and symptomatic) P51S carriers.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Sommen M, Wuyts W, Van Camp G (2017) Molecular diagnostics for hereditary hearing loss in children. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 17(8):751–760

Shearer AE, Hildebrand MS, Smith RJH (1993–2019) Hereditary hearing loss and deafness overview. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Stephens K, Amemiya A (eds) Genereviews (R), University of Washington, Seattle

Verhagen WI, Huygen PL, Joosten EM (1988) Familial progressive vestibulocochlear dysfunction. Arch Neurol 45(7):766–768

Manolis EN et al (1996) A gene for non-syndromic autosomal dominant progressive postlingual sensorineural hearing loss maps to chromosome 14q12–13. Hum Mol Genet 5(7):1047–1050

Fransen E et al (1999) High prevalence of symptoms of Meniere’s disease in three families with a mutation in the COCH gene. Hum Mol Genet 8(8):1425–1429

Verhagen WI et al (2000) Familial progressive vestibulocochlear dysfunction caused by a COCH mutation (DFNA9). Arch Neurol 57(7):1045–1047

De Belder J et al (2017) Does otovestibular loss in the autosomal dominant disorder DFNA9 have an impact of on cognition? A systematic review. Front Neurosci 11:735

Moher D et al (2009) Reprint–preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Phys Ther 89(9):873–880

Robertson NG et al (1998) Mutations in a novel cochlear gene cause DFNA9, a human nonsyndromic deafness with vestibular dysfunction. Nat Genet 20(3):299–303

Robertson NG et al (2001) Inner ear localization of mRNA and protein products of COCH, mutated in the sensorineural deafness and vestibular disorder, DFNA9. Hum Mol Genet 10(22):2493–2500

Robertson NG et al (2014) Cochlin in normal middle ear and abnormal middle ear deposits in DFNA9 and Coch (G88E/G88E) mice. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 15(6):961–974

Robertson NG et al (2006) Cochlin immunostaining of inner ear pathologic deposits and proteomic analysis in DFNA9 deafness and vestibular dysfunction. Hum Mol Genet 15(7):1071–1085

Robertson NG et al (2003) Subcellular localisation, secretion, and post-translational processing of normal cochlin, and of mutants causing the sensorineural deafness and vestibular disorder, DFNA9. J Med Genet 40(7):479–486

Robertson NG et al (2008) A targeted Coch missense mutation: a knock-in mouse model for DFNA9 late-onset hearing loss and vestibular dysfunction. Hum Mol Genet 17(21):3426–3434

Grabski R et al (2003) Mutations in COCH that result in non-syndromic autosomal dominant deafness (DFNA9) affect matrix deposition of cochlin. Hum Genet 113(5):406–416

Liepinsh E et al (2001) NMR structure of the LCCL domain and implications for DFNA9 deafness disorder. Embo j 20(19):5347–5353

Trexler M, Banyai L, Patthy L (2000) The LCCL module. Eur J Biochem 267(18):5751–5757

Bae SH et al (2014) Identification of pathogenic mechanisms of COCH mutations, abolished cochlin secretion, and intracellular aggregate formation: genotype–phenotype correlations in DFNA9 deafness and vestibular disorder. Hum Mutat 35(12):1506–1513

Yao J et al (2010) Role of protein misfolding in DFNA9 hearing loss. J Biol Chem 285(20):14909–14919

Py BF et al (2013) Cochlin produced by follicular dendritic cells promotes antibacterial innate immunity. Immunity 38(5):1063–1072

Eavey RD et al (2000) Mutations in COCH (formerly Coch5b2) cause DFNA9. Adv Otorhinolaryngol 56:101–102

Ikezono T et al (2001) Identification of the protein product of the Coch gene (hereditary deafness gene) as the major component of bovine inner ear protein. Biochim Biophys Acta 1535(3):258–265

Khetarpal U (2000) DFNA9 is a progressive audiovestibular dysfunction with a microfibrillar deposit in the inner ear. Laryngoscope 110(8):1379–1384

Merchant SN, Linthicum FH, Nadol JB Jr (2000) Histopathology of the inner ear in DFNA9. Adv Otorhinolaryngol 56:212–217

Nagy I, Trexler M, Patthy L (2008) The second von Willebrand type A domain of cochlin has high affinity for type I, type II and type IV collagens. FEBS Lett 582(29):4003–4007

Verhagen WI et al (2001) Hereditary cochleovestibular dysfunction due to a COCH gene mutation (DFNA9): a follow-up study of a family. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci 26(6):477–483

de Kok YJ et al (1999) A Pro51Ser mutation in the COCH gene is associated with late onset autosomal dominant progressive sensorineural hearing loss with vestibular defects. Hum Mol Genet 8(2):361–366

Bom SJ et al (1999) Progressive cochleovestibular impairment caused by a point mutation in the COCH gene at DFNA9. Laryngoscope 109(9):1525–1530

Fransen E, Van Camp G (1999) The COCH gene: a frequent cause of hearing impairment and vestibular dysfunction? Br J Audiol 33(5):297–302

Verstreken M et al (2001) Hereditary otovestibular dysfunction and Meniere’s disease in a large Belgian family is caused by a missense mutation in the COCH gene. Otol Neurotol 22(6):874–881

Lemaire FX et al (2003) Progressive late-onset sensorineural hearing loss and vestibular impairment with vertigo (DFNA9/COCH): longitudinal analyses in a belgian family. Otol Neurotol 24(5):743–748

Bom SJ et al (2001) Speech recognition scores related to age and degree of hearing impairment in DFNA2/KCNQ4 and DFNA9/COCH. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 127(9):1045–1048

Bom SJ et al (2003) Cross-sectional analysis of hearing threshold in relation to age in a large family with cochleovestibular impairment thoroughly genotyped for DFNA9/COCH. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 112(3):280–286

Bischoff AM et al (2005) Vestibular deterioration precedes hearing deterioration in the P51S COCH mutation (DFNA9): an analysis in 74 mutation carriers. Otol Neurotol 26(5):918–925

Bischoff AM et al (2007) Vertical corneal striae in families with autosomal dominant hearing loss: DFNA9/COCH. Am J Ophthalmol 143(5):847–852

Hildebrand MS et al (2009) Mutation in the COCH gene is associated with superior semicircular canal dehiscence. Am J Med Genet A 149A(2):280–285

Alberts B et al (2018) Bayesian quantification of sensory reweighting in a familial bilateral vestibular disorder (DFNA9). J Neurophysiol 119(3):1209–1221

Fransen E et al (2001) A common ancestor for COCH related cochleovestibular (DFNA9) patients in Belgium and The Netherlands bearing the P51S mutation. J Med Genet 38(1):61–65

de Varebeke SP et al (2014) Focal sclerosis of semicircular canals with severe DFNA9 hearing impairment caused by a P51S COCH-mutation: is there a link? Otol Neurotol 35(6):1077–1086

Kemperman MH et al (2002) DFNA9/COCH and its phenotype. Adv Otorhinolaryngol 61:66–72

Kemperman MH et al (2005) Audiometric, vestibular, and genetic aspects of a DFNA9 family with a G88E COCH mutation. Otol Neurotol 26(5):926–933

Vermeire K et al (2006) Good speech recognition and quality-of-life scores after cochlear implantation in patients with DFNA9. Otol Neurotol 27(1):44–49

Cremers CW et al (2005) From gene to disease; a progressive cochlear-vestibular dysfunction with onset in middle-age (DFNA9). Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 149(47):2619–2621

JanssensdeVarebeke SPF et al (2018) Bi-allelic inactivating variants in the COCH gene cause autosomal recessive prelingual hearing impairment. Eur J Hum Genet 26(4):587–591

Parzefall T et al (2018) Identification of a rare COCH mutation by whole-exome sequencing: implications for personalized therapeutic rehabilitation in an Austrian family with non-syndromic autosomal dominant late-onset hearing loss. Wien Klin Wochenschr 130(9–10):299–306

ISO 7029:2017 (2017) Statistical distribution of hearing thresholds related to age and gender. Acoustics. https://www.iso.org/standard/42916.html

Collin RW et al (2006) Identification of a novel COCH mutation, G87W, causing autosomal dominant hearing impairment (DFNA9). Am J Med Genet A 140(16):1791–1794

Pauw RJ et al (2007) Clinical characteristics of a Dutch DFNA9 family with a novel COCH mutation, G87W. Audiol Neurootol 12(2):77–84

Pauw RJ et al (2007) Phenotype description of a novel DFNA9/COCH mutation, I109T. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 116(5):349–357

Huygen PLM, Cremers PR (2003) CWRJ, Characterizing and distinguishing progressive phenotypes in nonsyndromic autosomal dominant hearing impairment. Audiol Med 1:37–46

Fernandez C, Goldberg JM (1971) Physiology of peripheral neurons innervating semicircular canals of the squirrel monkey. II. Response to sinusoidal stimulation and dynamics of peripheral vestibular system. J Neurophysiol 34(4):661–675

Van Der Stappen A, Wuyts FL, Van De Heyning PH (2000) Computerized electronystagmography: normative data revisited. Acta Otolaryngol 120(6):724–730

Usami S et al (2003) Mutations in the COCH gene are a frequent cause of autosomal dominant progressive cochleo-vestibular dysfunction, but not of Meniere’s disease. Eur J Hum Genet 11(10):744–748

Huygen PL, Verhagen WI, Nicolasen MG (1989) Correlation between velocity step and caloric response parameters. Acta Otolaryngol 108(5–6):368–371

Maes L et al (2008) Normative data and test-retest reliability of the sinusoidal harmonic acceleration test, pseudorandom rotation test and velocity step test. J Vestib Res 18(4):197–208

Jongkees LB (1973) Vestibular tests for the clinician. Arch Otolaryngol 97(1):77–80

Wuyts FL et al (2007) Vestibular function testing. Curr Opin Neurol 20(1):19–24

Hain TC, Cherchi M, Yacovino DA (2013) Bilateral vestibular loss. Semin Neurol 33(3):195–203

Maes L et al (2017) Comparison of the motor performance and vestibular function in infants with a congenital cytomegalovirus infection or a connexin 26 mutation: a preliminary study. Ear Hear 38(1):e49–e56

Curthoys IS (2010) A critical review of the neurophysiological evidence underlying clinical vestibular testing using sound, vibration and galvanic stimuli. Clin Neurophysiol 121(2):132–144

Funding

There are no funding to report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

The study is a systematic review, and therefore, with a retrospective design. Therefore, informant consent was not applicable for this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

JanssensdeVarebeke, S., Topsakal, V., Van Camp, G. et al. A systematic review of hearing and vestibular function in carriers of the Pro51Ser mutation in the COCH gene. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 276, 1251–1262 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-019-05322-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-019-05322-x