Abstract

Linear motion perceptual thresholds (PTs) were compared between patients with Menière’s disease (MD) and vestibular migraine (VM). Twenty patients with VM, 27 patients with MD and 34 healthy controls (HC) were examined. PTs for linear motion along the inter-aural (IA), naso-occipital axes (NO), and head-vertical (HV) axis were measured using a multi-axis motion platform. Ocular and cervical vestibular evoked myogenic potentials (o/c VEMP) were performed and the dizziness handicap inventory (DHI) administered. In order to discriminate between VM and MD, we also evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of applied methods. PTs depended significantly on the group tested (VM, MD and HC), as revealed by ANCOVA with group as the factor and age as the covariate. This was true for all motion axes (IA, HV and NO). Thresholds were highest for MD patients, significantly higher than for all other groups for all motion axes, except for the IA axis when compared with HC group suggesting decreased otolith sensitivity in MD patients. VM patients had thresholds that were not different from those of HC, but were significantly lower than those of the MD group for all motion axes. The cVEMP p13 latencies differed significantly across groups being lowest in VM. There was a statistically significant association between HV and NO thresholds and cVEMP PP amplitudes. Diagnostic accuracy was highest for the IA axis, followed by cVEMP PP amplitudes, NO and HV axes. To conclude, patients with MD had significantly higher linear motion perception thresholds compared to patients with VM and controls. Except for reduced cVEMP latency, there were no differences in c/oVEMP between MD, VM and controls.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Vestibular migraine (VM) is a frequent vestibular syndrome characterized by recurrent vertigo attacks of moderate or severe intensity in association with aura and migrainous headaches [1, 2]. This can be difficult to differentiate from Menière’s disease (MD), which is also characterized by episodic vertigo with additional fluctuating hearing loss, aural fullness and tinnitus [3]. A correct diagnosis is crucial for a successful treatment, as patients suffering acute vertigo attacks are neither capable to work nor to participate in daily activities such as driving a car [4]. Even the demonstration of endolymphatic hydrops (EH) by locally enhanced inner ear imaging (LEIM) [5] does not discriminate because EH has been found in both diseases [6]. In addition, patients with MD often develop migrainous headaches, and vice versa, patients with VM can suffer from hearing problems [7, 8]. These findings imply that there is a significant clinical overlap between VM and MD with a need for additional testing to differentiate between them.

A well-known phenomenon in VM is motion hypersensitivity accompanied by motion sickness [9–11]. We therefore hypothesized that perceptual thresholds (PTs), defined as the stimulus magnitude at which subjects can first perceive the motion direction despite the noise inherent in sensory transduction and subsequent neural processing [12], would be reduced in VM [13]. PT testing might therefore be helpful for VM–MD differentiation. In fact, reduced PTs in VM compared to healthy controls have been observed previously [13], but only during mid-frequency roll rotation while upright, which stimulates both otoliths and canals. In contrast, here we test linear motion thresholds, which should rely predominantly on otolith function. We expected linear motion thresholds to be elevated in MD because of previous reports that MD negatively impacts otolith function [14, 15]. We also investigated otolith function by ocular and cervical vestibular evoked myogenic potentials (c/oVEMP). Further, the dizziness handicap inventory (DHI) was applied to assess the individual functional impairment of patients depending on diagnosis, motion thresholds and VEMP. These methods are similar to those we have used previously [16], but here we focus specifically on the problem of differentiating VM from MD. Diagnostic accuracy of all applied methods for discriminating between VM and MD pathologies is also assessed and compared.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

Patients were recruited from the interdisciplinary outpatient clinic. The study included 20 patients with definite or probable VM [11 females (F), mean age 40.9 years] according to the recent diagnostic criteria [2], 27 patients with clinically probable or definite MD (13 F, 58 years), according to the recent current criteria [3], as well as a group of 34 healthy subjects with no prior history of dizziness, neurologic or neurootologic disease (21 F, 44.6 years). All patients had a standardized neurologic and neuro-ophthalmologic examination, including video-oculography with caloric irrigation. All patients with VM had normal caloric irrigation testing, as defined by the mean peak slow phase velocity (mPSPV) of vestibular nystagmus >5°/s, whereas patients with MD had a lowered canal excitability with the mPSPV of <5°/s on the affected ear. The study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki II Declaration and approved by the ethics committee of the Ludwig-Maximilians University Medical Faculty. All participants gave their informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study.

Recording of ocular VEMP

Examination was performed in the supine position with subjects’ upper bodies at a 30° angle from the horizontal. To ensure maximum upgaze was maintained subjects fixated a small target at the mini-shaker margin, i.e. superomedial gaze of approximately 30°. This angle is reported to elicit the largest responses [17, 18]. “Mini tap” stimuli were administered with a Bruel and Kjaer Mini-Shaker Type 4810 (2-ms clicks positive polarity at 2 Hz) at the Fz cranial site (in the midline at the hairline, 30 % of the distance between the inion and nasion). These taps generate an acceleration wave that propagates to the mastoid bilaterally, leading to an outward linear stimulation of the utricles. A cleaning and de-greasing procedure was performed with abrasive paste before recording. The recording electrode was placed over the contralateral inferior oblique muscle (centered beneath the pupil and 3 mm below the eye), the reference electrode was placed on the chin, and a ground electrode was placed under the chin. Responses were averaged over 50–100 stimuli. n10 and p15 were identified as the first negative and positive peaks that occurred between 10 and 20 ms after stimulus onset, respectively. Responses were amplified by a Bruel and Kjaer Type 2718 power amplifier (voltage gain 30 dB). Unrectified signals were averaged with filter cutoffs of 20–500 Hz. n10 amplitude [19] and latency were taken as dependent measures. These methods are very similar to those used previously [16].

Recording of cervical VEMP

Examination was performed in the same supine position for cVEMPs. In addition, subjects were instructed to lift the head to generate the active neck flexion that is needed during cVEMP and recording of tonic background muscle activity. Tone bursts were played monaurally via intro-aurical speakers with foam ear-tips (Air-conducted 500-Hz, 125-dB SPL). A recording electrode was located at the belly of the ipsilateral sternocleidomastoid muscle, a reference electrode was placed on the manubrium sterni, and a ground electrode was placed on the forehead. EMG responses to 50–100 stimuli were averaged after activity was amplified and bandpass filtered (Nicolet Biomedical Inc, Madison WI, USA). p13 and n23 were defined as the first positive and negative peaks occurring between 13 and 23 ms after stimulus onset, respectively. The p13 latency and the corrected peak-to-peak amplitude (PP) were taken as the dependent measures; this amplitude is defined as the difference between the p13 and n23 peaks. Correction was performed by taking the ratio of PP amplitude divided by the mean EMG activity over the recording period [20]. These methods are very similar to those used previously [16].

Linear motion perception threshold testing

To measure perceptual thresholds, subjects were physically moved while seated on a hexapod motion platform (Moog 6DOF2000E). They sat in a padded racing seat and wore a 5-point harness. The head was cradled in a form-fitted vacuum pillow and secured with a forehead strap. To cancel and mask the sound of the moving platform, white noise was played through noise cancellation headphones. To eliminate visual cues, blackout goggles were worn. A wireless numeric keypad was used to collect responses. On each trial, a 1-s linear movement was presented in one of two opposite directions and subjects indicated the direction that they had moved, a two-alternative-forced-choice task. A raised cosine velocity profile with frequency 1 Hz was presented. Axis of movement depended on the condition, either (1) left or right along the inter-aural (IA) axis, (2) forward or backward along the naso-occipital (NO) axis, or (3) up or down along the head-vertical (HV) axis. Each condition was run in a separate block; blocks were run in a random order for each subject.

To assess threshold, movement magnitude was varied from trial to trial using a staircase procedure. The largest stimulus was a 15 cm displacement (peak acceleration, 94.25 cm/s2); displacement was decreased by one-third with every step down on the staircase (15, 10, 6.66 cm, etc.). Duration was fixed at 1-s, so displacement, velocity, and acceleration scaled together. Each block started with the largest displacement (15 cm). Achieved acceleration was not measured but in previous work, we have verified that the platform reproduces the desired trajectories very accurately [21].

The staircase began using a 1-up-1-down stepping rule. Stimulus magnitude was decreased after a correct answer and increased after an incorrect answer. This allowed the staircase to converge quickly to smaller magnitudes where performance was close to chance level. The staircase rule was changed after four reversals (i.e., a step down followed by a step up or a step up followed by a step down). For remaining block a 2-down-1-up (2D1U) stepping rule was used. Stimulus magnitude was reduced after two consecutive correct answers, and increased after each incorrect answer. A total of fifty trials were performed, and this required ~8 min/axis (Fig. 1a). Several prior studies of vestibular perception have used similar methods [22–27]. A psychometric function was fit to the data from each block using a maximum likelihood method [28, 29] to find the stimulus magnitude that results in 84 % correct performance, i.e., one standard deviation from chance (50 %) performance (Fig. 1b). This quantifies the standard deviation of the noise on the perceptual self-motion estimate [24, 30]. Because the range of motion of the platform is limited, thresholds could not be reliably measured above an upper limit.Thus, threshold was assigned equal to the largest stimulus magnitude (94.25 cm/s2) where performance was <84 % correct at the largest stimulus. These methods are very similar to those used previously [16].

Example of individual staircase history (a) and psychometric fit (b). The 2D1U staircase terminated after 50 trials. Filled and unfilled points show correct and incorrect responses, respectively. b Cumulative Gaussian fit to data from (a). Proportion of correct responses is plotted as a function of the log of the stimulus magnitude. Threshold is the stimulus value corresponding to 84 % correct shown by red dashed lines in a and b

Dizziness handicap inventory

To quantitatively assess the self-perceived impairment in daily life, subjects were administered the dizziness handicap inventory (DHI). The DHI is a 25-item questionnaire developed for quantifying the impact of dizziness on everyday life. It is divided in three parts: physical, functional and emotional. Each question may be answered as “yes”, “sometimes” and “no” with a “yes” response yielding a score of 4, “sometimes” response a score of 2 and “no” a score of 0. The overall as well as subscale (physical, functional and emotional) scores were computed (DHI_T, DHI_P, DHI_F, DHI_E). The test version, as published in 1990 [31], was used. The DHI was set to 0 in healthy controls, as they had no prior history of dizziness, neurologic or neurootologic disease.

Statistical analysis

Analysis and graph design was performed using SPSS version 22.0 (IBM, New York, NY, USA). A univariate analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was run to determine if there were mean differences in vestibular thresholds, oVEMP and cVEMP amplitude and latencies, and DHI between three study groups (VM, MD, HC) after controlling for age. Post hoc analysis was performed with a Bonferroni adjustment. Outliers were excluded; these were defined as values outside the mean ± 2SD for a particular axis and group. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients were computed to compare vestibular physiological test measures and age in controls. Receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC), with VM representing a positive actual state and MD a negative one, was applied to visualize the potential quantitative cut-points for differentiating VM from MD and to find out the tradeoff between sensitivity and specificity of performed measures. Classification performance of each measure was described using the area under the curve (AUC). In order to identify the optimal cut-point we used the Youden Index (J); the Youden index is a function of the sensitivity (q) and the specificity (p) of a classifier and is defined as: \(J = q + p - 1\). The optimal cut-point was defined as the one maximizing J.

Results

Linear motion thresholds

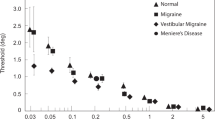

Threshold data by group and axis are displayed in Fig. 2a–c, and mean threshold values are listed in Table 1. After adjustment for age, there was a statistically significant difference in perceptual thresholds between the groups (IA: F = 3.387, p = 0.025; HV: F = 6.595, p = 0.002; NO: F = 8.844, p = 0.000368) as revealed by ANCOVA performed for each motion axis separately. Highest thresholds were observed for the MD group, and post hoc tests among the groups (Table 2) revealed that these thresholds were significantly higher than those of the other groups for all motion axes, except for IA axis when compared with HC group (Fig. 3). In contrast, the lowest thresholds were observed for the VM group; these thresholds were significantly lower than for the MD group for all motion axes. When comparing thresholds across axes regardless of subject group (Fig. 2d), there was a trend for HV thresholds to be higher than thresholds for the other axes (F = 2.954, p = 0.054), being highest in the MD group (Table 2). Perceptual thresholds between groups were subtracted to obtain delta (Δ) values. The highest values were observed for comparison of VM and MD groups along the NO axis (Fig. 3). Linear motion perception thresholds were significantly correlated with age (p < 0.01), as tested by Spearman correlation analysis (IA: r = 0.384, HV: r = 0.341, NO: r = 0.445).

Vestibular perceptual thresholds (PTs). a Inter-aural (IA) axis, b Head-vertical (HV) axis, c Naso-occipital (NO) axis. Lines show linear fits by study group. Vestibular migraine (VM) indicated by yellow diamonds and dashed line. Menière’s disease (MD) indicated by blue circles and solid line. Healthy controls (HC) indicated by green triangles and dotted line. d Thresholds replotted for all study groups to compare axes: IA, HV, and NO, indicated by dark blue, red, and light blue circles and lines, respectively

Discrimination between VM and MD

An overview of the ROC analysis for each measure is shown in Table 3. The most robust measure according to the AUC was the IA threshold (AUC = 0.848, 95 % CI 0.737–0.959, p = p < 0.001), followed by the cVEMP PP amplitudes (AUC = 0.796, 95 % CI 0.647–0.944, p = 0.001), NO axis (AUC = 0.789, 95 % CI 0.657–0.921, p = 0.001) and HV axis (AUC = 0.775, 95 % CI 0.628–0.923, p = 0.002). Ocular VEMP amplitudes and latencies and DHI questionnaire were not diagnostically relevant.

Ocular and cervical VEMP testing

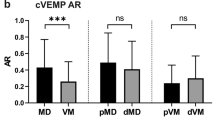

Mean o/cVEMP values are listed in Table 1. The cVEMP PP amplitudes did not significantly differ among the study groups (F = 0.972, p = 0.383), but the cVEMP p13 latencies tended to be reduced in VM (F = 3.104; p = 0.040; post hoc: VM vs. MD group: p = 0.052, VM vs. HC group: p = 0.097, MD vs. HC group: p = 1.0). Across groups there was a statistically significant association between thresholds and cVEMP PP amplitudes for HV and NO axes, but this association did not reach significance for the IA axis (IA-cVEMP: r = −0.175, p = 0.139; HV-cVEMP: r = −0.254; p = 0.034; NO-cVEMP: r = −0.251; p = 0.034).

The oVEMP amplitudes and latency showed no significant differences or trends based on ANCOVA across the patient groups (n10-latency: F = 0.670, p = 0.514; n10 amplitudes: F = 0.355, p = 0.702). Across groups there were no significant associations between thresholds and oVEMP n10 amplitudes (IA-oVEMP: r = 0.096, p = 0.402; HV-oVEMP: r = 0.146, p = 0.207; NO-oVEMP: r = 0.028, p = 0.812).

Dizziness handicap inventory

DHI, a measure of the subjective impairment, did not differ between analyzed groups (DHI_T: F = 0.010, p = 0.919; DHI_P: F = 0.34, p = 0.855; DHI_F: F = 0.75, p = 0.785; DHI_E: F = 0.11, p = 0.917). There was no statistically significant relationship between DHI and thresholds (DHI-IA: r = −0.047, p = 0.770; DHI-HV: r = −0.054, p = 0.742; DHI-NO: r = −0.152, p = 0.342) or o-/cVEMP n10/PP amplitudes (oVEMP: r = −0.163, p = 0.155; cVEMP: r = 0.136, p = 0.403).

Discussion

The major findings of this study were as follows: first, thresholds were significantly elevated in patients with MD, as expected due to underlying vestibular deficits. This difference was most observable for HV thresholds, which reinforces the evidence of predominantly saccular dysfunction in these patients [5, 32]. Second, thresholds were lowest in VM, but not significantly lower than thresholds measured in HC. This finding supports the hypothesis that VM does not result from a general increased vestibular sensitivity. Instead, as previously suggested, increased vestibular sensitivity in VM could be a manifestation of abnormal central integration of canal and otolith signals, perhaps at the level of the caudal cerebellar vermis [33]. Other mechanisms such as increased excitability in thalamus [34] or alteration of brain regions characteristic for pain, multisensory vestibular processing and central vestibular compensation [35] in patients suffering VM may also play a role. Finally, analysis of the diagnostic accuracy revealed that thresholds are a good clinical tool to discriminate between VM and MD patients.

Perceptual thresholds allow for the measurement of perceptual function and separate testing of linear and angular motion sensitivity along or around different axes, which allows independent assessment of particular vestibular organs (i.e., utricle, saccule, and horizontal and vertical canals [16, 30, 36, 37]). For these reasons, PTs have the potential to become a highly relevant clinical diagnostic method in future.

At present, the standard method to assess otolith function in the clinic is using VEMP. Therefore, we also assessed whether VEMP allow differentiation between study groups, and whether VEMP are correlated with PTs. Prior studies have reported that amplitudes of cVEMP, thought to reflect saccular function, are reduced in VM [38] and MD [39] compared to healthy controls, but we found no significant differences among groups. Nevertheless, the correlation between cVEMP PP amplitudes and PTs was significant for HV and NO axes, both of which rely partly (NO) or predominantly (HV) on saccular function, since the sacculus is oriented approximately in the sagittal plane of the head. While this correlation was not observed in our previous study [16], we nevertheless interpret this as an indication that both cVEMP and PTs can provide some measure of saccular function. Interestingly, the highest threshold difference (Table 2; Fig. 3) was observed for the NO and HV axes, consistent with the suggestion that saccular impairment allows distinguishing between VM and MD disease. This also explains the finding that cVEMP amplitudes, which assess saccular function, showed good sensitivity and specificity and high AUC in terms of differentiation between VM and MD patients. However, PTs may be more useful for differential diagnosis. PTs use real motion stimuli, which may lead to an advantage over cVEMP, which incorporate variability arising from across subject differences in anatomy affecting propagation of the acoustic stimulus from the speaker to the end organ. PTs also assess perceptual rather than motor function.

In contrast with cVEMP PP amplitudes, cVEMP latencies differed significantly across subject groups, being noticeably reduced in VM. As discussed above, this might reflect an increased vestibular sensitivity due to abnormal central integration of canal and otolith signals in VM. However, this result was not observed in a prior study of cVEMP in VM [38]. oVEMP provide a measure of utricular function. Our previous study [16] found an association between oVEMP n10 amplitudes and PTs (IA and NO axes), but this association was not observed in the present study, perhaps due to the higher frequency stimulus used to assess PTs (1 vs 0.5 Hz). Nor did we observe that oVEMP n10 amplitudes or latencies differed significantly across study groups, in line with previous results showing that oVEMP response does not allow separation between VM and MD [40]. These findings do not seem unexpected, because the involvement of the utricle has been reported to be less than that of the saccule in MD [15, 41]. The midline taps are relatively vigorous stimuli that may require greater utricular impairment to show abnormal responses [42]. Ocular VEMP seem to have little diagnostic relevance for VM–MD discrimination because diagnostic accuracy was the poorest of the applied tests along with the DHI questionnaire. This is also supported by prior studies showing a high interrater variability of the oVEMP method, which is very sensitive to measurement conditions [43].

Finally, analyses of PTs across patient groups are in line with previous studies. PTs along the HV axis were higher than along the IA and NO axes, probably reflecting reduced sensitivity to the predominantly vertical oscillations associated with bipedal locomotion [22, 24]. In addition, we observed a significant increase in PTs with age along all three axes, in line with prior studies [44].

In conclusion, it appears that PTs constitute a reliable technique to differentiate VM and MD, particularly for HV head motion, which depends on saccular function. VM thresholds were not reduced relative to HC, suggesting VM is not associated with a general increase in vestibular perceptual sensitivity; heightened motion sensitivity in these patients has been observed only for specific motion types [13].

References

Dieterich M, Brandt T (1999) Episodic vertigo related to migraine (90 cases): vestibular migraine? J Neurol 246:883–892

Lempert T, Olesen J, Furman J et al (2012) Vestibular migraine: diagnostic criteria. J Vestib Res Equilib Orientat 22:167–172. doi:10.3233/VES-2012-0453

Lopez-Escamez JA, Carey J, Chung W-H et al (2015) Diagnostic criteria for Menière’s disease. J Vestib Res Equilib Orientat 25:1–7. doi:10.3233/VES-150549

Strupp M, Thurtell MJ, Shaikh AG et al (2011) Pharmacotherapy of vestibular and ocular motor disorders, including nystagmus. J Neurol 258:1207–1222

Gürkov R, Flatz W, Louza J et al (2012) In vivo visualized endolymphatic hydrops and inner ear functions in patients with electrocochleographically confirmed Menière’s disease. Otol Neurotol Off Publ Am Otol Soc Am Neurotol Soc Eur Acad Otol Neurotol 33:1040–1045. doi:10.1097/MAO.0b013e31825d9a95

Gürkov R, Kantner C, Strupp M et al (2013) Endolymphatic hydrops in patients with vestibular migraine and auditory symptoms. Eur Arch Oto Rhino Laryngol Off J Eur Fed Oto Rhino Laryngol Soc EUFOS Affil Ger Soc Oto Rhino Laryngol Head Neck Surg. doi:10.1007/s00405-013-2751-2

Neff BA, Staab JP, Eggers SD et al (2012) Auditory and vestibular symptoms and chronic subjective dizziness in patients with Menière’s disease, vestibular migraine, and Menière’s disease with concomitant vestibular migraine. Otol Neurotol Off Publ Am Otol Soc Am Neurotol Soc Eur Acad Otol Neurotol 33:1235–1244. doi:10.1097/MAO.0b013e31825d644a

Radtke A, von Brevern M, Neuhauser H et al (2012) Vestibular migraine Long-term follow-up of clinical symptoms and vestibulo-cochlear findings. Neurology 79:1607–1614. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e31826e264f

Boldingh MI, Ljostad U, Mygland A, Monstad P (2011) Vestibular sensitivity in vestibular migraine: VEMPs and motion sickness susceptibility. Cephalalgia 31:1211–1219

Sharon JD, Hullar TE (2013) Motion sensitivity and caloric responsiveness in vestibular migraine and Meniere’s disease. Laryngoscope. doi:10.1002/lary.24285

Furman JM, Marcus DA (2012) Migraine and motion sensitivity. Contin Minneap Minn 18:1102–1117. doi:10.1212/01.CON.0000421621.18407.96

Merfeld DM (2011) Signal detection theory and vestibular thresholds: I. Basic theory and practical considerations. Exp Brain Res Exp Hirnforsch Exp Céréb 210:389–405. doi:10.1007/s00221-011-2557-7

Lewis RF, Priesol AJ, Nicoucar K et al (2011) Dynamic tilt thresholds are reduced in vestibular migraine. J Vestib Res Equilib Orientat 21:323–330. doi:10.3233/VES-2011-0422

Sajjadi H, Paparella MM (2008) Meniere’s disease. Lancet 372:406–414

Okuno T, Sando I (1987) Localization, frequency, and severity of endolymphatic hydrops and the pathology of the labyrinthine membrane in Menière’s disease. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 96:438–445

Agrawal Y, Bremova T, Kremmyda O et al (2013) Clinical testing of otolith function: perceptual thresholds and myogenic potentials. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol JARO 14:905–915. doi:10.1007/s10162-013-0416-x

Kantner C, Gürkov R (2014) The effects of commonly used upward gaze angles on ocular vestibular evoked myogenic potentials. Otol Neurotol Off Publ Am Otol Soc Am Neurotol Soc Eur Acad Otol Neurotol 35:289–293. doi:10.1097/MAO.0b013e318299a812

Govender S, Rosengren SM, Colebatch JG (2009) The effect of gaze direction on the ocular vestibular evoked myogenic potential produced by air-conducted sound. Clin Neurophysiol Off J Int Fed Clin Neurophysiol 120:1386–1391. doi:10.1016/j.clinph.2009.04.017

Nguyen KD, Welgampola MS, Carey JP (2010) Test-retest reliability and age-related characteristics of the ocular and cervical vestibular evoked myogenic potential tests. Otol Neurotol Off Publ Am Otol Soc Am Neurotol Soc Eur Acad Otol Neurotol 31:793–802. doi:10.1097/MAO.0b013e3181e3d60e

Welgampola MS, Colebatch JG (2005) Characteristics and clinical applications of vestibular-evoked myogenic potentials. Neurology 64:1682–1688

MacNeilage PR, Turner AH, Angelaki DE (2010) Canal-otolith interactions and detection thresholds of linear and angular components during curved-path self-motion. J Neurophysiol 104:765–773. doi:10.1152/jn.01067.2009

Benson AJ, Spencer MB, Stott JR (1986) Thresholds for the detection of the direction of whole-body, linear movement in the horizontal plane. Aviat Space Environ Med 57:1088–1096

Grabherr L, Nicoucar K, Mast FW, Merfeld DM (2008) Vestibular thresholds for yaw rotation about an earth-vertical axis as a function of frequency. Exp Brain Res 186:677–681. doi:10.1007/s00221-008-1350-8

MacNeilage PR, Banks MS, DeAngelis GC, Angelaki DE (2010) Vestibular heading discrimination and sensitivity to linear acceleration in head and world coordinates. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci 30:9084–9094. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1304-10.2010

Mallery RM, Olomu OU, Uchanski RM et al (2010) Human discrimination of rotational velocities. Exp Brain Res 204:11–20. doi:10.1007/s00221-010-2288-1

Roditi RE, Crane BT (2012) Directional asymmetries and age effects in human self-motion perception. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol JARO 13:381–401. doi:10.1007/s10162-012-0318-3

Valko Y, Lewis RF, Priesol AJ, Merfeld DM (2012) Vestibular labyrinth contributions to human whole-body motion discrimination. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci 32:13537–13542. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2157-12.2012

Prins N (2012) The psychometric function: the lapse rate revisited. J Vis. doi:10.1167/12.6.25

Wichmann FA, Hill NJ (2001) The psychometric function: I. Fitting, sampling, and goodness of fit. Percept Psychophys 63:1293–1313

Merfeld DM, Priesol A, Lee D, Lewis RF (2010) Potential solutions to several vestibular challenges facing clinicians. J Vestib Res Equilib Orientat 20:71–77. doi:10.3233/VES-2010-0347

Jacobson GP, Newman CW (1990) The development of the dizziness handicap inventory. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 116:424–427

Yamane H, Sunami K, Iguchi H et al (2012) Assessment of Meniere’s disease from a radiological aspect—saccular otoconia as a cause of Meniere’s disease? Acta Otolaryngol Stockh 132:1054–1060. doi:10.3109/00016489.2012.680980

King S, Wang J, Priesol AJ, Lewis RF (2014) Central integration of canal and otolith signals is abnormal in vestibular migraine. Front Neurol 5:233. doi:10.3389/fneur.2014.00233

Russo A, Marcelli V, Esposito F et al (2014) Abnormal thalamic function in patients with vestibular migraine. Neurology 82:2120–2126. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000000496

Obermann M, Wurthmann S, Steinberg BS et al (2014) Central vestibular system modulation in vestibular migraine. Cephalalgia Int J Headache. doi:10.1177/0333102414527650

Priesol AJ, Valko Y, Merfeld DM, Lewis RF (2014) Motion perception in patients with idiopathic bilateral vestibular hypofunction. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg Off J Am Acad Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 150:1040–1042. doi:10.1177/0194599814526557

Kingma H (2005) Thresholds for perception of direction of linear acceleration as a possible evaluation of the otolith function. BMC Ear Nose Throat Disord 5:5. doi:10.1186/1472-6815-5-5

Baier B, Stieber N, Dieterich M (2009) Vestibular-evoked myogenic potentials in vestibular migraine. J. Neurol 256:1447–1454

Baier B, Dieterich M (2009) Vestibular-evoked myogenic potentials in “vestibular migraine” and Menière’s disease: a sign of an electrophysiological link? Ann N Y Acad Sci 1164:324–327. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.03868.x

Zuniga MG, Janky KL, Schubert MC, Carey JP (2012) Can vestibular-evoked myogenic potentials help differentiate Ménière disease from vestibular migraine? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg Off J Am Acad Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 146:788–796. doi:10.1177/0194599811434073

Paparella MM (1985) The cause (multifactorial inheritance) and pathogenesis (endolymphatic malabsorption) of Meniere’s disease and its symptoms (mechanical and chemical). Acta Otolaryngol Stockh 99:445–451

Taylor RL, Wijewardene AA, Gibson WPR et al (2011) The vestibular evoked-potential profile of Menière’s disease. Clin Neurophysiol Off J Int Fed Clin Neurophysiol 122:1256–1263. doi:10.1016/j.clinph.2010.11.009

Ertl M, Boegle R, Kirsch V, Dieterich M (2015) On the impact of examiners on latencies and amplitudes in cervical and ocular vestibular-evoked myogenic potentials evaluated over a large sample (N = 1,038). Eur Arch Oto Rhino Laryngol Off J Eur Fed Oto Rhino Laryngol Soc EUFOS Affil Ger Soc Oto Rhino Laryngol Head Neck Surg. doi:10.1007/s00405-015-3510-3

Roditi RE, Crane BT (2012) Directional asymmetries and age effects in human self-motion perception. JARO J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 13:381–401. doi:10.1007/s10162-012-0318-3

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

T. Bremova and N. Böttcher received honoraria for lecturing from Actelion. A. Caushaj, M. Ertl, P. MacNeilage, R. Strobl report no disclosures. M. Strupp is Joint Chief Editor of the Journal of Neurology, Editor in Chief of Frontiers of Neuro-otology and Section Editor of F1000. He has received speaker’s honoraria from Abbott, Actelion, Biogen, Eisai, GSK, Henning Pharma, Interacoustics, MSD, Otometrics, Pierre-Fabre, TEVA, UCB. He acts as a consultant for Abbott and Actelion.

Study funding

Supported by German Ministry of Education and Research grant code 01 EO 0901 to the German Center for Vertigo and Balance Disorders at the University of Munich, Campus Großhadern.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Bremova, T., Caushaj, A., Ertl, M. et al. Comparison of linear motion perception thresholds in vestibular migraine and Menière’s disease. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 273, 2931–2939 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-015-3835-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-015-3835-y