Abstract

Purpose

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) surgery is performed with and without concomitant hysterectomy depending on a variety of factors. The objective was to compare 30-day major complications following POP surgery with and without concomitant hysterectomy.

Methods

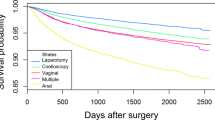

This was a retrospective cohort study using the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) multicenter database to compare 30-day complications using Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for POP with or without concomitant hysterectomy. Patients were grouped by procedure: Vaginal prolapse repair (VAGINAL), minimally invasive sacrocolpopexy (MISC), and open abdominal sacrocolpopexy (OASC). 30-day postoperative complications and other relevant data were evaluated in patients who underwent concomitant hysterectomy compared to those who did not. Multivariable logistic regression models assessed the association of concomitant hysterectomy on 30-day major complications stratified by surgical approach.

Results

60,201 women undergoing POP surgery comprised our cohort. Within 30 days of surgery, there were 1722 major complications in 1432 patients (2.4%). Prolapse surgery alone had a significantly lower overall complication rate than with concomitant hysterectomy (1.95% vs 2.81%; p < .001). Multivariable analysis revealed odds of complications following POP surgery was higher among women who underwent concomitant hysterectomy compared to those who did not have hysterectomy in VAGINAL (OR 1.53, 95% CI 1.36–1.72), OASC (OR 2.70, 95% CI 1.69–4.33), and overall (OR 1.46, 95% CI 1.31–1.62), but not in MISC (OR 0.99, 95% CI 0.67–1.46.)

Conclusion

Concomitant hysterectomy at the time of pelvic organ prolapse (POP) surgery increases the risk of 30-day postoperative complications in comparison to prolapse surgery alone in our overall cohort.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The ACS NSQIP Participant User File is available to any individual who has an official appointment at a fully enrolled ACS-NSQIP site.

References

Barber MD, Maher C (2013) Epidemiology and outcome assessment of pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J 24(11):1783–1790

(2019) Pelvic Organ Prolapse: ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 214. Obstet Gynecol 134(5)

Heisler CA et al (2009) Effect of additional reconstructive surgery on perioperative and postoperative morbidity in women undergoing vaginal hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol 114(4):720–726

Swift S et al (2005) Pelvic Organ Support Study (POSST): the distribution, clinical definition, and epidemiologic condition of pelvic organ support defects. Am J Obstet Gynecol 192(3):795–806

Boyles SH, Weber AM, Meyn L (2003) Procedures for pelvic organ prolapse in the United States, 1979–1997. Am J Obstet Gynecol 188(1):108–115

Ko KJ, Lee KS (2019) Current surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse: strategies for the improvement of surgical outcomes. Investig Clin Urol 60(6):413–424

Oh S et al (2021) Comparison of treatment outcomes for native tissue repair and sacrocolpopexy as apical suspension procedures at the time of hysterectomy for uterine prolapse. Sci Rep 11(1):3119

Fairchild PS et al (2016) Rates of colpopexy and colporrhaphy at the time of hysterectomy for prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol 214(2):262.e1-262.e7

Dallas K et al (2018) Association between concomitant hysterectomy and repeat surgery for pelvic organ prolapse repair in a cohort of nearly 100,000 women. Obstet Gynecol 132(6):1328–1336

Fuchshuber PR et al (2012) The power of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program–achieving a zero pneumonia rate in general surgery patients. Perm J 16(1):39–45

Moon AS et al (2020) Robotic surgery in gynecology. Surg Clin North Am 100(2):445–460

Sajadi KP, Goldman HB (2015) Robotic pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Nat Rev Urol 12(4):216–224

Rardin CR (2011) Minimally invasive urogynecology. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 38(4):639–649

Winkelman WD, Modest AM, Richardson ML (2021) The surgical approach to abdominal sacrocolpopexy and concurrent hysterectomy: trends for the past decade. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg 27(1):e196–e201

Inan AH et al (2019) The incidence, causes, and management of lower urinary tract injury during total laparoscopic hysterectomy. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod 48(1):45–49

Matthews CA, Gebhart JB (2022) Avoiding and managing lower urinary tract injuries during pelvic surgery. In: Walters & Karram Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery. Elsevier, Inc. pp 386–398

Visco AG et al (2001) Cost-effectiveness of universal cystoscopy to identify ureteral injury at hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol 97(5 Pt 1):685–692

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JMS: manuscript writing/editing. EDH: project development, data collection, data analysis, manuscript writing/editing. EBH: project development, data analysis, manuscript writing/editing. KMB: project development, data analysis, manuscript writing/editing. JAO: project development, manuscript writing/editing.

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethics approval

This is a retrospective coding study and was deemed IRB exempt.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Selle, J.M., Hokenstad, E.D., Habermann, E.B. et al. The effect of concomitant hysterectomy on complications following pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Arch Gynecol Obstet 309, 321–327 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-023-07112-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-023-07112-7