Abstract

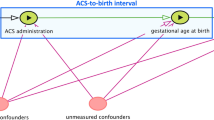

Administration of antenatal corticosteroids (ACS) for accelerating foetal lung maturation in threatened preterm birth is one of the cornerstones of prevention of neonatal mortality and morbidity. To identify the optimal timing of ACS administration, most studies have compared subgroups based on treatment-to-delivery intervals. Such subgroup analysis of the first placebo-controlled randomised controlled trial indicated that a one to seven day interval between ACS administration and birth resulted in the lowest rates of neonatal respiratory distress syndrome. This efficacy window was largely confirmed by a series of subgroup analyses of subsequent trials and observational studies and strongly influenced obstetric management. However, these subgroup analyses suffer from a methodological flaw that often seems to be overlooked and potentially has important consequences for drawing valid conclusions. In this commentary, we point out that studies comparing treatment outcomes between subgroups that are retrospectively identified at birth (i.e. after randomisation) may not only be plagued by post-randomisation confounding bias but, more importantly, may not adequately inform decision making before birth, when the projected duration of the interval is still unknown. We suggest two more formal interpretations of these subgroup analyses, using a counterfactual framework for causal inference, and demonstrate that each of these interpretations can be linked to a different hypothetical trial. However, given the infeasibility of these trials, we argue that none of these rescue interpretations are helpful for clinical decision making. As a result, guidelines based on these subgroup analyses may have led to suboptimal clinical practice. As an alternative to these flawed subgroup analyses, we suggest a more principled approach that clearly formulates the question about optimal timing of ACS treatment in terms of the protocol of a future randomised study. Even if this ‘target trial’ would never be conducted, its protocol may still provide important guidance to avoid repeating common design flaws when conducting observational ‘real world’ studies using statistical methods for causal inference.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Not applicable

References

Liggins GC, Howie RN (1972) A controlled trial of antepartum glucocorticoid treatment for prevention of the respiratory distress syndrome in premature infants. Pediatrics 50(4):515–525

Crowley PA (1995) Antenatal corticosteroid therapy: A meta-analysis of the randomized trials, 1972 to 1994. Am J Obstet Gynecol 173(1):322–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(95)90222-8

Kemp MW, Schmidt AF, Jobe AH (2019) Optimizing antenatal corticosteroid therapy. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 24(3):176–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.siny.2019.05.003

World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations on Interventions to Improve Preterm Birth Outcomes.; 2015. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0928-8244(98)00076-5. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240057296. Accessed 26 November 2022.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Preterm Labour and Birth. NICE Guideline; 2015. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng25. Accessed 26 November 2022.

Wynne K, Rowe C, Delbridge M, Watkins B, Brown K, Addley J, Woods A, Murray H. Antenatal corticosteroid administration for foetal lung maturation. F1000Res. 2020;9:F1000 Faculty Rev-219. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.20550.1.

Roberts D, Dalziel SR. Antenatal corticosteroids for accelerating fetal lung maturation for women at risk of preterm birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(3):CD004454. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004454.pub2

Roberts D, Brown J, Medley N, Dalziel SR. Antenatal corticosteroids for accelerating fetal lung maturation for women at risk of preterm birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;(3): CD004454. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004454.pub3

Crowther CA, Haslam RR, Hiller JE, Doyle LW, Robinson JS (2006) Neonatal respiratory distress syndrome after repeat exposure to antenatal corticosteroids: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 367(9526):1913–1919. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68846-6

Altini M, Rossetti E, Rooijakkers M, et al. Combining electrohysterography and heart rate data to detect labour. In: 2017 IEEE EMBS International Conference on Biomedical & Health Informatics (BHI). IEEE; 2017:149–152. https://doi.org/10.1109/BHI.2017.7897227

Carter J, Seed PT, Watson HA et al (2020) Development and validation of predictive models for QUiPP App vol 2: tool for predicting preterm birth in women with symptoms of threatened preterm labor. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 55(3):357–367. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.20422

Hernán MA, Robins JM (2016) Using big data to emulate a target trial when a randomized trial is not available. Am J Epidemiol 183(8):758–764. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwv254

Didelez V. Should the analysis of observational data always be preceded by specifying a target experimental trial? Int J Epidemiol. April 2016:dyw032. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyw032

Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i4919

Goodman SN, Schneeweiss S, Baiocchi M (2017) Using design thinking to differentiate useful from misleading evidence in observational research. JAMA 317(7):705. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.19970

Labrecque JA, Swanson SA (2017) Target trial emulation: teaching epidemiology and beyond. Eur J Epidemiol 32(6):473–475. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-017-0293-4

Ring AM, Garland JS, Stafeil BR, Carr MH, Peckman GS, Pircon RA (2007) The effect of a prolonged time interval between antenatal corticosteroid administration and delivery on outcomes in preterm neonates: a cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 196(5):457.e1-457.e6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2006.12.018

Waters TP, Mercer B (2009) Impact of timing of antenatal corticosteroid exposure on neonatal outcomes. J Matern Neonatal Med 22(4):311–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767050802559095

Wilms FF, Vis JY, Pattinaja DAPM et al (2011) Relationship between the time interval from antenatal corticosteroid administration until preterm birth and the occurrence of respiratory morbidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol 205(1):49.e1-49.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2011.03.035

Kuk JY, An JJ, Cha HH et al (2013) Optimal time interval between a single course of antenatal corticosteroids and delivery for reduction of respiratory distress syndrome in preterm twins. Am J Obstet Gynecol 209(3):256.e1-256.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2013.06.020

Melamed N, Shah J, Soraisham A et al (2015) Association between antenatal corticosteroid administration-to-birth interval and outcomes of preterm neonates. Obstet Gynecol 125(6):1377–1384. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000000840

Kosinska-Kaczynska K, Szymusik I, Urban P, Zachara M, Wielgos M (2016) Relation between time interval from antenatal corticosteroids administration to delivery and neonatal outcome in twins. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 42(6):625–631. https://doi.org/10.1111/jog.12966

Yasuhi I, Myoga M, Suga S et al (2017) Influence of the interval between antenatal corticosteroid therapy and delivery on respiratory distress syndrome. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 43(3):486–491. https://doi.org/10.1111/jog.13242

Lau HCQ, Tung JSZ, Wong TTC, Tan PL, Tagore S (2017) Timing of antenatal steroids exposure and its effects on neonates. Arch Gynecol Obstet 296(6):1091–1096. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-017-4543-1

Frändberg J, Sandblom J, Bruschettini M, Maršál K, Kristensen K (2018) Antenatal corticosteroids: a retrospective cohort study on timing, indications and neonatal outcome. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 97(5):591–597. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.13301

Gates S, Brocklehurst P (2007) Decline in effectiveness of antenatal corticosteroids with time to birth: Real or artefact? Br Med J 335(7610):77–79. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39225.677708.80

Hernán MA, Hernández-Díaz S, Robins JM (2004) A Structural Approach to Selection Bias. Epidemiology 15:615–625

Hernán MA, Hernández-Díaz S, Robins JM. Randomized Trials Analyzed as Observational Studies. Ann Intern Med 2013;560–563.https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-159-8-201310150-00709.

Mansournia MA, Higgins JPT, Sterne JAC, Hernán MA (2017) Biases in randomized trials: a conversation between trialists and epidemiologists. Epidemiology 28:54–59

Hernán MA (2005) Invited commentary: hypothetical interventions to define causal effects—afterthought or prerequisite? Am J Epidemiol 162(7):618–620. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwi255

Hernán MA (2016) Does water kill? A call for less casual causal inferences. Ann Epidemiol 26(10):674–680. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2016.08.016

Robins JM (1986) A new approach to causal inference in mortality studies with a sustained exposure period—application to control of the healthy worker survivor effect. Math Model 7:1393–1512

Hernán MA, Robins JM (2020) Causal Inference: What If. Chapman & Hall/CRC, Boca Raton

Pearl J. Causality: Models, Reasoning, and Inference. Cambridge University Press; 2009.

Kemp MW, Saito M, Schmidt AF et al (2020) The duration of fetal antenatal steroid exposure determines the durability of preterm ovine lung maturation. Am J Obstet Gynecol 222(2):183.e1-183.e9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2019.08.046

Kleinrouweler CE, Cheong-See FM, Collins GS, Kwee A, Thangaratinam S, Khan KS, Mol BW, Pajkrt E, Moons KG, Schuit E (2016) Prognostic models in obstetrics: available, but far from applicable. Am J Obstet Gynecol 214(1):79-90.e36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2015.06.013

Murphy SA, Van der Laan MJ, Robins JM et al (2001) Marginal mean models for dynamic regimes. J Am Stat Assoc 96(456):1410–1423. https://doi.org/10.1198/016214501753382327

Hernán MA, Lanoy E, Costagliola D, Robins JM (2006) Comparison of dynamic treatment regimes via inverse probability weighting. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 98(3):237–242. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-7843.2006.pto_329.x

The HIV-CAUSAL Collaboration (2011) When to Initiate Combined Antiretroviral Therapy to Reduce Mortality and AIDS-Defining Illness in HIV-Infected Persons in Developed Countries. Ann Intern Med 154(8):509. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-154-8-201104190-00001

Murphy SA (2003) Optimal dynamic treatment regimes. J R Stat Soc 65:331–355

Robins JM. Optimal Structural Nested Models for Optimal Sequential Decisions. In: Heagerty DYL and P, editor. Proc Second Seattle Symp Biostat. New York, NY: Springer; 2004. p. 189–326.

Chakraborty B, Moodie EEM. Statistical methods for dynamic treatment regimes. reinforcement learning, causal inference, and personalized medicine. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2013. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-7428-9

Cain LE, Saag MS, Petersen M et al (2016) Using observational data to emulate a randomized trial of dynamic treatment-switching strategies: an application to antiretroviral therapy. Int J Epidemiol 45(6):2038–2049. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyv295

García-Albéniz X, Hsu J, Hernán MA (2017) The value of explicitly emulating a target trial when using real world evidence: an application to colorectal cancer screening. Eur J Epidemiol 32(6):495–500. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-017-0287-2

Dickerman BA, García-Albéniz X, Logan RW, Denaxas S, Hernán MA (2019) Avoidable flaws in observational analyses: an application to statins and cancer. Nat Med 25(10):1601–1606. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-019-0597-x

Robins JM (1989) The control of confounding by intermediate variables. Stat Med 8(6):679–701. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.4780080608

VanderWeele TJ, Mumford SL, Schisterman EF (2012) Conditioning on Intermediates in Perinatal Epidemiology. Epidemiology 23(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e31823aca5d

Acknowledgements

We thank Stijn Vansteelandt and Mats Stensrud for helpful comments.

Funding

Isabelle Dehaene was funded by a scholarship of FWO (1700520N). The funding body played no role in the creation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ID: project development, manuscript writing and editing, other: revision. JS: project development, manuscript writing and editing, other: visualisation, revision. OD: manuscript editing. COP: manuscript editing. KDC: other: supervision. KS: other: supervision. KR: manuscript editing, other: supervision. JD: supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Dehaene, I., Steen, J., Dukes, O. et al. On optimal timing of antenatal corticosteroids: time to reformulate the question. Arch Gynecol Obstet 308, 1085–1091 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-023-06941-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-023-06941-w