Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the proportion of severely growth-restricted singleton births < 3rd percentile (proxy for severe fetal growth restriction; FGR) undelivered at 40 weeks (FGR_40), and compare maternal characteristics and outcomes of FGR_40 births and FGR births at 37–39 weeks’ (FGR_37–39) to those not born small-for-gestational-age at term (Not SGA_37+).

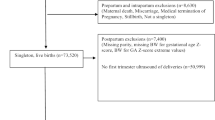

Methods

The annual rates of singleton FGR_40 births from 2006 to 2015 were calculated using data from linked Western Australian population health datasets. Using 2013–2015 data, maternal factors associated with FGR births were investigated using multinomial logistic regression to estimate odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) while relative risks (RR) of birth outcomes between each group were calculated using Poisson regression. Neonatal adverse outcomes were identified using a published composite indicator (diagnoses, procedures and other factors).

Results

The rate of singleton FGR_40 births decreased by 23.0% between 2006 and 2015. Factors strongly associated with FGR_40 and FGR_37–39 births compared to Not SGA_37+ births included the mother being primiparous (ORs 3.13: 95% CI 2.59–3.79; 1.69, 95% CI 1.47, 1.94, respectively) and ante-natal smoking (ORs 2.55, 95% CI 1.97, 3.32; 4.48, 95% CI 3.74, 5.36, respectively). FGR_40 and FGR_37–39 infants were more likely to have a neonatal adverse outcome (RRs 1.70, 95% CI 1.41, 2.06 and 2.46 95% CI 2.18, 2.46, respectively) compared to Not SGA 37+ infants.

Conclusions

Higher levels of poor perinatal outcomes among FGR births highlight the importance of appropriate management including fetal growth monitoring. Regular population-level monitoring of FGR_40 rates may lead to reduced numbers of poor outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

22 July 2020

Unfortunately, after publication, we found errors in the extraction of data on gestational diabetes and threatened miscarriage.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- LHT:

-

Linear hypothesis test

- MNS:

-

Midwives Notification System

- Not SGA 37+:

-

Birth at 37 or more weeks’ gestation without SGA

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- RCOG:

-

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

- RR:

-

Relative risk

- SGA:

-

Small-for-gestational-age

- FGR:

-

Fetal growth restriction (< 3rd percentile)

- FGR_37–39:

-

Severely growth-restricted birth delivered at 37–39 weeks’ gestation

- FGR_40:

-

Severely growth-restricted birth undelivered at 40 weeks’ gestation

References

Gardosi J, Madurasinghe V, Williams M, Malik A, Francis A (2013) Maternal and fetal risk factors for stillbirth: population based study. BMJ 346:f108. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f108

Chauhan SP, Rice MM, Grobman WA, Bailit J, Reddy UM, Wapner RJ, Varner MW, Thorp JM Jr, Leveno KJ, Caritis SN, Prasad M, Tita ATN, Saade G, Sorokin Y, Rouse DJ, Tolosa JE, Msce ftEKSNIoCH, Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units N (2017) Neonatal morbidity of small- and large-for-gestational-age neonates born at term in uncomplicated pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol 130(3):511–519. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000002199

Lindqvist PG, Molin J (2005) Does antenatal identification of small-for-gestational age fetuses significantly improve their outcome? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 25(3):258–264. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.1806

Unterscheider J, Daly S, Geary MP, Kennelly MM, McAuliffe FM, O'Donoghue K, Hunter A, Morrison JJ, Burke G, Dicker P, Tully EC, Malone FD (2013) Optimizing the definition of intrauterine growth restriction: the multicenter prospective PORTO Study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 208(4):290–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2013.02.007

Francis JH, Permezel M, Davey MA (2014) Perinatal mortality by birthweight centile. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 54(4):354–359. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajo.12205

Savchev S, Sanz-Cortes M, Cruz-Martinez R, Arranz A, Botet F, Gratacos E, Figueras F (2013) Neurodevelopmental outcome of full-term small-for-gestational-age infants with normal placental function. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 42(2):201–206. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.12391

Barker DJ (2006) Adult consequences of fetal growth restriction. Clin Obstet Gynecol 49(2):270–283

McCowan LM, Roberts CT, Dekker GA, Taylor RS, Chan EH, Kenny LC, Baker PN, Moss-Morris R, Chappell LC, North RA, Consortium S (2010) Risk factors for small-for-gestational-age infants by customised birthweight centiles: data from an international prospective cohort study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 117(13):1599–1607. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02737.x

Monier I, Blondel B, Ego A, Kaminski M, Goffinet F, Zeitlin J (2016) Does the presence of risk factors for fetal growth restriction increase the probability of antenatal detection? A French National Study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 30(1):46–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppe.12251

Caradeux J, Martinez-Portilla RJ, Peguero A, Sotiriadis A, Figueras F (2019) Diagnostic performance of third-trimester ultrasound for the prediction of late-onset fetal growth restriction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 220(5):449–459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2018.09.043

McCowan LM, Harding JE, Stewart AW (2005) Customized birthweight centiles predict SGA pregnancies with perinatal morbidity. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 112(8):1026–1033. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00656.x

McCowan LM, Figueras F, Anderson NH (2018) Evidence-based national guidelines for the management of suspected fetal growth restriction: comparison, consensus, and controversy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 218(2S):S855–S868. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2017.12.004

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (2014) The Investigation and Management of the Small-for-Gestational-Age Fetus. Green-top Guideline No. 31, 2nd Edition. Green-top Guideline No. 31, 2nd edn. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

Francis A, Hugh O, Gardosi J (2018) Customized vs INTERGROWTH-21(st) standards for the assessment of birthweight and stillbirth risk at term. Am J Obstet Gynecol 218(2S):S692–S699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2017.12.013

Hunt R, Davey M, Anil S, Kenny S, Wills G, Simon D, Wallace E, on behalf of the, Perinatal Safety, and Quality Committee (2018) Victorian perinatal services performance indicators report 2016–17. Safer Care Victoria, Victorian Government, Melbourne

Davey M-A (2018) Management of severe fetal growth restriction (FGR): improved with enhanced reporting? Paper presented at the PSANZ 2018 Auckland

Hunt RW, Ryan-Atwood TE, Hudson R, Wallace E, Anil S, on behalf of the, Perinatal Safety, and Quality Committee (2019) Victorian perinatal services performance indicators report 2017–18. Safer Care Victoria, Victorian Government, Melbourne

Centre of Research Excellence Stillbirth (2019) Safer Baby Bundle Handbook and Resource Guide: Working together to reduce stillbirth, vol Version 1.9. Australia

Holman CDJ, Bass AJ, Rouse IL, Hobbs MST (1999) Population-based linkage of health records in Western Australia: development of a health services research linked database. Aust N Z J Public Health 23(5):453–459

Dobbins TA, Sullivan EA, Roberts CL, Simpson JM (2012) Australian national birthweight percentiles by sex and gestational age, 1998–2007. Med J Aust 197(5):291–294

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2016) Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS): Volume 5—Remoteness Structure. (Catalogue No 1270.0.55.005)

Australian Government Department of Health (2018) Clinical practice guidelines: pregnancy care. Australian Government Department of Health, Canberra

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2011) Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA) (Catalogue No 2033.0.55.001)

Hanley GE, Hutcheon JA, Kinniburgh BA, Lee L (2017) Interpregnancy interval and adverse pregnancy outcomes: an analysis of successive pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol 129(3):408–415. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000001891

Regan AK, Ball SJ, Warren JL, Malacova E, Padula A, Marston C, Nassar N, Stanley F, Leonard H, de Klerk N, Pereira G (2019) A population-based matched-sibling analysis estimating the associations between first interpregnancy interval and birth outcomes. Am J Epidemiol 188(1):9–16. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwy188

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2016) Standard Australian Classification of Countries (SACC). (Catalogue No 1269.0)

Lain SJ, Algert CS, Nassar N, Bowen JR, Roberts CL (2012) Incidence of severe adverse neonatal outcomes: use of a composite indicator in a population cohort. Matern Child Health J 16(3):600–608. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-011-0797-6

Armitage P (1955) Tests for linear trends in proportions and frequencies. Biometrics 11(3):375–386. https://doi.org/10.2307/3001775

Cochran WG (1954) Some methods for strengthening the common χ2 tests. Biometrics 10(4):417–451. https://doi.org/10.2307/3001616

Zou G (2004) A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol 159(7):702–706. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwh090

Diksha P, Permezel M, Pritchard N (2018) Why we miss fetal growth restriction: Identification of risk factors for severely growth-restricted fetuses remaining undelivered by 40 weeks gestation. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 58(6):674–680. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajo.12818

Downey F (2007) Validation Study of the Western Australian Midwives’ Notification System. 2005 Data, Perth

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2015) 4364.0.55.001 National Health Survey: First Results Australia 2014–15

Hilder L, Flenady V, Ellwood D, Donnolley N, Chambers GM (2018) Improving, but could do better: trends in gestation-specific stillbirth in Australia, 1994–2015. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppe.12508

Adams N, Tudehope D, Gibbons KS, Flenady V (2018) Perinatal mortality disparities between public care and private obstetrician-led care: a propensity score analysis. BJOG 125(2):149–158. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.14903

Australian Council on Healthcare Standards (2012) Australasian Clinical Indicator Report 2004–2011, 13th edn. ACHS, Sydney

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2016) National core maternity indicators—stage 3 and 4: results from 2010–2013. AIHW National Perinatal Epidemiology and Statistics Unit, Canberra

Ganzevoort W, Thilaganathan B, Baschat A, Gordijn SJ (2019) Point. Am J Obstet Gynecol 220(1):74–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2018.10.007

Gardosi J (2019) Counterpoint. Am J Obstet Gynecol 220(1):74–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2018.10.006

Mozooni M, Preen DB, Pennell CE (2018) Stillbirth in Western Australia, 2005–2013: the influence of maternal migration and ethnic origin. Med J Aust 209(9):394–400

Davies-Tuck ML, Davey MA, Wallace EM (2017) Maternal region of birth and stillbirth in Victoria, Australia 2000–2011: a retrospective cohort study of Victorian perinatal data. PLoS ONE 12(6):e0178727. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0178727

Drysdale H, Ranasinha S, Kendall A, Knight M, Wallace EM (2012) Ethnicity and the risk of late-pregnancy stillbirth. Med J Aust 197(5):278–281

Small R, Gagnon A, Gissler M, Zeitlin J, Bennis M, Glazier R, Haelterman E, Martens G, McDermott S, Urquia M, Vangen S (2008) Somali women and their pregnancy outcomes postmigration: data from six receiving countries. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 115(13):1630–1640. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01942.x

Khalil A, Rezende J, Akolekar R, Syngelaki A, Nicolaides KH (2013) Maternal racial origin and adverse pregnancy outcome: a cohort study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 41(3):278–285. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.12313

Balchin I, Whittaker JC, Patel RR, Lamont RF, Steer PJ (2007) Racial variation in the association between gestational age and perinatal mortality: prospective study. BMJ 334(7598):833. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39132.482025.80

Ekeus C, Cnattingius S, Essen B, Hjern A (2011) Stillbirth among foreign-born women in Sweden. Eur J Public Health 21(6):788–792. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckq200

von Katterfeld B, Li J, McNamara B, Langridge AT (2012) Perinatal complications and cesarean delivery among foreign-born and Australian-born women in Western Australia, 1998–2006. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 116(2):153–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.09.012

Selvaratnam R, Davey M, Wallace E, Oats J, Anil S, McDonald S (2018) Improve the detection and management of severe fetal growth restriction (FGR) in Victoria. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 58(Supplement 1):75–75

Delnord M, Zeitlin J (2019) Epidemiology of late preterm and early term births—an international perspective. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 24(1):3–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.siny.2018.09.001

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the Data Linkage Branch (Western Australian Government Department of Health), the custodians of the Midwives’ Notification System, Birth and Death Registries, Hospital Morbidity Data Collection and Western Australian Register of Developmental Anomalies for providing data for this project. In particular, we acknowledge Dr Rosi Katich, Senior Coding Consultant, WA Clinical Coding Authority (WA Department of Health) who advised us on the International Classification of Diseases-10-AM classification in relation to the neonatal adverse outcome index. We also acknowledge Dr Samantha Lain, Children’s Hospital at Westmead Clinical School, University of Sydney, who developed the neonatal adverse outcome index and provided advice about it.

Funding

This research was supported by funding from an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Project Grant (GNT1127265) which funded AAA, HDB, BMF and CCJS. Research at UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health is supported by the NIHR Great Ormond Street Hospital Biomedical Research Centre (PH).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HDB: project development, data management and analysis, manuscript writing; AAA, BMF, SWW, PH: critical revision of the manuscript; CCJS: project development, critical revision of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed were in accordance with the ethical standards of Western Australian Department of Health Human Ethics Research Committee and the Western Australian Aboriginal Health Ethics Committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Consent for the study was obtained from the data custodians. As the study was based on routinely collected anonymised population health data, individual consent from the participants was not obtained.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bailey, H.D., Adane, A.A., Farrant, B.M. et al. Profile of severely growth-restricted births undelivered at 40 weeks in Western Australia. Arch Gynecol Obstet 301, 1383–1396 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-020-05537-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-020-05537-y