Abstract

Objective

Chlamydia trachomatis infection is the most common bacterial sexual transmitted disease. Nearly 75% of all cases appear clinically unapparent and can cause, especially when getting chronically, infertility. Regarding pregnancy, a nationwide screening for C. trachomatis was established since April 1995. The aim of this study was to determine the percentage of tested patients throughout these 7 years to evaluate the execution of the German guidelines.

Materials and methods

Between 2001 and 2007, 12,865 patients were evaluated retrospectively concerning a Chlamydia trachomatis testing.

Results

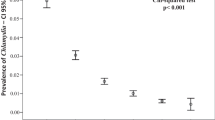

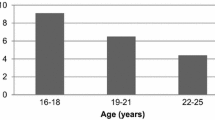

A test was performed for chlamydial infection in 10,088 patients (78.4%). 65 pregnant patients (0.5%) out of 1,008 tested patients were positive for Chlamydia trachomatis. The part of tested patients was rising significantly from 2001 to 2007. In 2001, 68.3% pregnant patients were tested. The number of screened patients increased continuously up to 85.2% in 2007 (p < 0.001). The percentage of positive tested patients ranged from 0.27% in 2003 to 0.74% in 2005 (mean 0.50%).

Conclusion

Since 1995, a screening for Chlamydia trachomatis has to be offered to every pregnant woman according to the German guidelines. The number of tested pregnant patients was rising from 68.3 to 85.2% within the evaluated 7 years, which would be a necessary and welcome trend. Interestingly, the mean prevalence of 0.5% of positive tested patients in this analysed urban population seems to be very low. An explanation might be the usage of the point-of-care (POC) tests and its low sensitivity. Testing by nucleic acid amplification might lead to a higher detection rate. Although the awareness concerning Chlamydia trachomatis testing during pregnancy seems to have been changed over the recent years, these data are still dissatisfactory.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Dixon RE, Hwang SJ, Hennig GW et al (2009) Chlamydia infection causes loss of pacemaker cells and inhibits oocyte transport in the mouse oviduct. Biol Reprod 80(4):665–673

Stephenson JM (1998) Screening for genital chlamydial infection. Br Med Bull 54:891–902

Barcelos MR, Vargas PR, Baroni C, Miranda AE (2008) Genital infections in women attending a Primary Unit of Health: prevalence and risk behaviors. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet 30:349–354

Chen MY, Fairley CK, De Guingand D et al (2009) Screening pregnant women for chlamydia: what are the predictors of infection? Sex Transm Infect 85:31–35

Lawton B, Rose S, Bromhead C, Brown S, MacDonald J, Shepherd J (2004) Rates of Chlamydia trachomatis testing and chlamydial infection in pregnant women. N Z Med J 117:U889

Allaire AD, Huddleston JF, Graves WL, Nathan L (1998) Initial and repeat screening for Chlamydia trachomatis during pregnancy. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 6:116–122

Andersen B, Ostergaard L, Thomsen RW, Schonheyder H (2007) Chlamydia trachomatis infection and risk of ectopic pregnancy. Sex Transm Dis 34:59 author reply 60

Bakken IJ, Skjeldestad FE, Lydersen S, Nordbo SA (2007) Births and ectopic pregnancies in a large cohort of women tested for Chlamydia trachomatis. Sex Transm Dis 34:739–743

Dutta R, Jha R, Salhan S, Mittal A (2008) Chlamydia trachomatis-specific heat shock proteins 60 antibodies can serve as prognostic marker in secondary infertile women. Infection 36:374–378

Egger M, Low N, Smith GD, Lindblom B, Herrmann B (1998) Screening for chlamydial infections and the risk of ectopic pregnancy in a county in Sweden: ecological analysis. BMJ 316:1776–1780

Baud D, Regan L, Greub G (2008) Emerging role of Chlamydia and Chlamydia-like organisms in adverse pregnancy outcomes. Curr Opin Infect Dis 21:70–76

Blas MM, Canchihuaman FA, Alva IE, Hawes SE (2007) Pregnancy outcomes in women infected with Chlamydia trachomatis: a population-based cohort study in Washington State. Sex Transm Infect 83:314–318

Cheney K, Wray L (2008) Chlamydia and associated factors in an under 20s antenatal population. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 48:40–43

Karowicz-Biliniska A, Kus E, Kazimiera W et al (2007) Chlamydia trachomatis infection and bacterial analysis in pregnant women in II and III trimester of pregnancy. Ginekol Pol 78:787–791

Ghazal-Aswad S, Badrinath P, Osman N, Abdul-Khaliq S, Mc Ilvenny S, Sidky I (2004) Prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis infection among women in a Middle Eastern community. BMC Womens Health 4:3

Clad A, Krause W (2007) Urogenital chlamydial infections in women and men. Hautarzt 58:13–17

Adams EJ, Charlett A, Edmunds WJ, Hughes G (2004) Chlamydia trachomatis in the United Kingdom: a systematic review and analysis of prevalence studies. Sex Transm Infect 80:354–362

Kulemann B, Meyer T, Clad A Chlamydien (2009) Wie effizient ist das Schwangerenscreening? Frauenarzt 50(3):204–206

Scholes D, Stergachis A, Heidrich FE, Andrilla H, Holmes KK, Stamm WE (1996) Prevention of pelvic inflammatory disease by screening for cervical chlamydial infection. N Engl J Med 334:1362–1366

Wilson JS, Honey E, Templeton A, Paavonen J, Mardh PA, Stray-Pedersen B (2002) A systematic review of the prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis among European women. Hum Reprod Update 8:385–394

Yasodhara P, Ramalakshmi BA, Naidu AN, Raman L (2001) Prevalence of specific IGM due to toxoplasma, rubella, CMV and C. trachomatis infections during pregnancy. Indian J Med Microbiol 19:52–56

Kinoshita-Moleka R, Smith JS, Atibu J et al (2008) Low prevalence of HIV and other selected sexually transmitted infections in 2004 in pregnant women from Kinshasa, the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Epidemiol Infect 136:1290–1296

Chen XS, Yin YP, Chen LP et al (2006) Sexually transmitted infections among pregnant women attending an antenatal clinic in Fuzhou, China. Sex Transm Dis 33:296–301

Cornetta Mda C, Goncalves AK, Bertini AM (2006) Efficacy of cytology for the diagnosis of Chlamydia trachomatis in pregnant women. Braz J Infect Dis 10:337–340

Currie MJ, Bowden FJ (2007) The importance of chlamydial infections in obstetrics and gynaecology: an update. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 47:2–8

Lenton JA, Freedman E, Hoskin K et al (2007) Chlamydia trachomatis infection among antenatal women in remote far west New South Wales, Australia. Sex Health 4:139–140

Mikhova M, Ivanov S, Nikolov A et al (2007) Cervicovaginal infections during pregnancy as a risk factor for preterm delivery. Akush Ginekol 46:27–31

Patel A, Rashid S, Godfrey EM, Panchal H (2008) Prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae genital infections in a publicly funded pregnancy termination clinic: empiric vs. indicated treatment? Contraception 78:328–331

Renton A, Thomas BM, Gill S, Lowndes C, Taylor-Robinson D, Patterson K (2006) Chlamydia trachomatis in cervical and vaginal swabs and urine specimens from women undergoing termination of pregnancy. Int J STD AIDS 17:443–447

Romoren M, Sundby J, Velauthapillai M, Rahman M, Klouman E, Hjortdahl P (2007) Chlamydia and gonorrhoea in pregnant Batswana women: time to discard the syndromic approach? BMC Infect Dis 7:27

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2006) Sexual transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. MMWR Recomm Rep 55(RR-11):1–94

Mendling W (2006) Vaginose, Vaginitis, Zervizitis und Salpingitis. 2 Aufl. Springer, Heidelberg

Conflict of interest statement

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Weissenbacher, T.M., Kupka, M.S., Kainer, F. et al. Screening for Chlamydia trachomatis in pregnancy: a retrospective analysis in a German urban area. Arch Gynecol Obstet 283, 1343–1347 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-010-1537-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-010-1537-7