Abstract

Fumarates (fumaric acid esters, FAEs) are orally administered systemic agents used for the treatment of psoriasis and multiple sclerosis. In 1994, a proprietary combination of FAEs was licensed for psoriasis by the German Drug Administration for use within Germany. Since then, fumarates have been established as one of the most commonly used treatments for moderate-to-severe psoriasis in Germany and other countries. The licensed FAE formulation contains dimethyl fumarate (DMF), as well as calcium, zinc, and magnesium salts of monoethyl fumarate (MEF). While the clinical efficacy of this FAE mixture is well established, the combination of esters on which it is based, and its dosing regimen, was determined empirically. Since the mid-1990s, the modes of action and contribution of the different FAEs to their overall therapeutic effect in psoriasis, as well as their adverse event profile, have been investigated in more detail. In this article, the available clinical data for DMF are reviewed and compared with data for the other FAEs. The current evidence substantiates that DMF is the main active compound, via its metabolic transformation to monomethyl fumarate (MMF). A recent phase III randomized and placebo-controlled trial including more than 700 patients demonstrated therapeutic equivalence when comparing the licensed FAE combination with DMF alone, in terms of psoriasis clearance according to the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) and Physician’s Global Assessment (PGA). Thus, DMF as monotherapy for the treatment of psoriasis is as efficacious as in combination with MEF, making the addition of such fumarate derivatives unnecessary.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin disease with various subtypes, of which chronic plaque psoriasis is the most common [21]. While mild disease is predominantly treated with topical agents, therapy of moderate-to-severe disease requires systemic treatment.

The role of fumarates in the therapy of psoriasis

Current guidelines provide an overview of appropriate systemic therapy for moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis with conventional and biological agents. Conventional oral systemic agents include acitretin, ciclosporin, methotrexate, and fumaric acid esters (FAEs; fumarates) [33]. FAEs are ester derivatives of FA (Table 1). Major derivatives of interest for oral therapy are dimethyl fumarate (DMF) and monoethyl fumarate (MEF) and its salts.

Schweckendiek was the first to propose in 1959 that psoriasis was caused by a disturbance involving FA in the citric acid cycle [5, 39]. Subsequently, Kiehl and Ionescu [18] described a defective purine nucleotide synthesis pathway in patients with psoriasis. These authors noted a correlation between increased adenosine triphosphate (ATP) levels in blood cells after administration of FA and FAEs and clearance of skin lesions. Although FA deficiency is not known as a cause of disease in humans, a proprietary mixture of FAEs (Fumaderm®, Biogen Idec), with an empirically determined dosing schedule, became established as a first-line systemic therapy for moderate-to-severe psoriasis in Germany, with a reported efficacy comparable to other systemic agents, such as methotrexate [41].

This particular FAE combination was first registered in Germany in 1994, and the current formulation is an enteric-coated tablet, available in two dosages (Fumaderm® initial and Fumaderm®), which contain DMF 30 mg or 120 mg and three salts of MEF, MEF-Ca (67 mg or 87 mg), MEF-Zn (both 3 mg) and MEF-Mg (both 5 mg), respectively [8]. Psorinovo® is a pharmacy-compounded DMF-only formulation (enteric-coated tablets, GMP Apotheek Mierlo-Hout) that is used to treat psoriasis in the Netherlands [35], where the local psoriasis treatment guidelines recommend FAEs as an induction treatment on moderate-to-severe disease [42]. In addition to psoriasis, DMF is used as the first-line therapy for relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis [4, 22, 23, 25]. A delayed-release oral formulation of DMF, Tecfidera® (120 and 240 mg), has been approved for this indication in Europe [15] and the US [9].

The safety profile of fumarates has been established through decades of clinical use. Adverse events (AEs) may affect up to two-thirds of patients [5, 38]. However, AEs are usually mild, and most commonly include gastrointestinal symptoms such as diarrhoea, stomach ache, cramps, increased frequency of stools, nausea, and vomiting [5, 26, 38]. Formulation research to address this problem has led to the delayed-release formulation of the currently licensed FAE combination [8]. Other common AEs include flush, leukocytopenia and lymphopenia [2, 17], and reversible peripheral eosinophilia. In fact, all FAE-containing products approved for treatment of psoriasis require periodic blood monitoring and, depending on the severity of lymphopenia, incorporate their own treatment discontinuation guidelines as part of their prescribing information, to prevent opportunistic infections [8]. A few cases of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), a rare, opportunistic viral infection of the central nervous system characterized by progressive inflammation and damage to the brain, have been reported with the use of FAEs in patients with long-standing and pronounced lymphopenia. In all cases, patients had not been appropriately monitored. PML is indeed a clinically relevant risk; however, the risk is believed to be minimal, should appropriate and periodic blood monitoring be carried out in FAE-treated patients [30].

In terms of their metabolism, FAEs are completely absorbed in the small intestine [28]. DMF has a half-life of approximately 12 min and is hydrolyzed to monomethyl fumarate (MMF; also known as methyl hydrogen fumarate, MHF) which has a half-life of 36 h [28]. MMF reaches peak plasma concentrations after 5–6 h, is metabolized via the citric acid cycle to fumaric acid, water and carbon dioxide, and is excreted mainly through the breath [28]. DMF is considered to act as a prodrug of MMF. DMF has been the primary orally administered fumarate of interest in most preclinical studies.

Much of the available data regarding the mode of action of FAEs in psoriasis have been obtained using the licensed FAE combination; however, the relative contributions of each FAE component to the therapeutic activity remained unclear. Despite its widespread acceptance in Germany, as an empirical mixture of different FAEs, this FAE combination remains unapproved for psoriasis elsewhere [26]. Current European S3 guidelines recommend FAEs for the short- and long-term treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis [33]. FAEs are also included in US guidelines, but with the caveat that they are not registered in that country [24]. The Cochrane Collaboration stated that while FAEs are superior to placebo for the treatment of psoriasis, there was still a need for more robust clinical trials and long-term safety data [5]. A recent phase III, double-blind, placebo-controlled study is a recent trial fulfilling such needs [32].

Altogether, an improved understanding of the relative contribution of each individual FAE compound toward their overall therapeutic effect in psoriasis is desirable. As a general principle, single-compound preparations (i.e. medicines with just one active pharmaceutical ingredient) are preferable over ‘combination products’ containing different active agents. The presence of compounds in a product that is not necessary for the therapeutic effect should be critically discussed, because of possible side effects.

The aim of this review is to evaluate the available clinical data regarding the effects of individual FAEs, in particular DMF and MEF, to describe the relative contribution of these compounds to the effectiveness of the approved FA mixture in the management of psoriasis.

Method

All relevant scientific publications relating to DMF and other FAEs were identified through a comprehensive search of the scientific literature. The databases searched were: PubMed/Medline and EMBASE (which includes the Cochrane library). Our search strategy included general chemical names for DMF and MEF and was not limited by any specific time period; thus, the entire database to January 23, 2018 was covered. To capture as many relevant hits as possible, the following search terms were used: (“dimethyl fumarate”) OR (“dimethylfumarate”) OR (“DMF”) OR (“ethyl fumarate”[NM]) OR (“monoethyl fumarate”) OR (“monoethylfumarate”) OR (“MEF”) OR (“monomethyl fumarate”) OR (“monomethylfumarate”) OR (“MMF”) OR (“Fumaric acid ester”) OR (“Fumaric acid ethyl ester”) OR (“Fumaric acid monoethyl ester”) OR (“fumaric acid monomethyl ester”). The search was narrowed down further by adding the term “psoriasis”. All retrieved citations were screened and the most relevant were selected for inclusion in this review. In addition, supplementary references were identified by searching through the bibliography cited within the retrieved publications.

Results

Clinical studies of FAEs in psoriasis

The efficacy of the FAEs in psoriasis was initially determined empirically. Many of the early clinical studies were not placebo controlled and without a comparator arm [1, 7, 19, 27, 37]. Nieboer et al. were first to explore the differences between FAEs systematically [37]. In a series of five open/controlled studies in small numbers of patients, they verified MEF monotherapy as being not superior to placebo as assessed by a Psoriasis Severity Score (PSS). In contrast, DMF monotherapy was superior to placebo [37]. Results of these studies are summarized in Table 2. DMF 240 mg daily significantly improved PSS scores over 6 weeks in study III, and in the long-term continuation study V (4–9 months) it was shown that DMF monotherapy led to moderate or considerable improvement in 22 and 33% of patients, respectively (Table 2). In contrast, 240 mg daily of MEF-Na had no benefit vs. placebo in study II. While a higher Na-MEF dose (720 vs. 240 mg; study IV) was associated with greater improvements in skin scaling and itching, there was no relevant difference between the two arms in the number of patients with considerable (> 50%) improvement (n = 3 in both groups).

Gastrointestinal complaints led to discontinuation in 20–27% of patients receiving DMF treatment [37]. Mild and reversible liver and kidney function abnormalities were noted with MEF 720 mg/day and DMF 240 mg/day. Almost 60% of patients treated with DMF alone experienced lymphopenia (mean % lymphocyte counts in peripheral blood in these patients dropped from 21.9 to 11.5%). However, this resolved approximately 6 months after treatment discontinuation. Interestingly, there was a statistically significant correlation between a ≥ 50% PSS improvement and lymphopenia (p < 0.01) during DMF therapy [37].

In 1990, a subsequent double-blind study by the same group (comparing DMF and a DMF plus MEF salts mixture) showed > 50% PSS improvement in 55% of 22 DMF and 80% of 23 DMF plus MEF patients after 4 months’ treatment. At the same time, a higher rate of treatment discontinuations in the combination arm (47 vs. 17%) was observed [36]. There were no significant differences between DMF and the DMF/MEF combination regarding the total PSS or individual parameters (e.g. extent of lesions, induration, scaling, redness and itching). Although treatment effects were seen a few days earlier with the DMF/MEF combination (n = 15) than with DMF alone (n = 18), all final scores after 4 months were not statistically different between the groups [36]. Overall, the results from these trials suggested that DMF is the active moiety in this formulation, and that the addition of other compounds may increase the risk of AEs without additional therapeutic benefit. On the basis of the above-mentioned studies, the FAE combination was approved in Germany.

Further evidence for the efficacy of DMF monotherapy was provided by Mrowietz et al. [31] in a randomized, double-blind and placebo-controlled study that fulfilled conditions for inclusion in the Cochrane review of Atwan et al. [5]. Randomized patients received an oral formulation of DMF 120 mg encapsulated as enteric-coated granules (microtablets). Patients with moderate-to-severe disease received 240 mg titrated over the first 7 days (n = 105) or placebo (n = 70) three times a day for 16 weeks. The median Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) reduction achieved with DMF was significantly higher than with placebo (67.8 vs. 10.2%; p < 0.001), and there was a 47% improvement in the Skindex-29 quality-of-life score when compared with placebo in the active treatment group. The most common AEs with DMF were gastrointestinal complaints (58 vs. 23% with placebo) and flush (42 vs. 9%). Gastrointestinal complaints were generally of mild or moderate severity and not treatment limiting [5, 31].

The encapsulated microtablet formulation of DMF was also investigated in a phase II multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study in Poland [20]. This trial included a 24-week, open-label safety-extension phase, and involved patients with chronic plaque, exanthematic guttate, erythrodermic, palmoplantar or pustular psoriasis of at least 1 year duration and a baseline PASI of 16–24. In the double-blind phase, 144 patients were randomized to placebo or to DMF 120, 360 or 720 mg daily for 12 weeks. A dose-related improvement with DMF vs. placebo was noted by 2 weeks, and the DMF formulation was well tolerated, with gastrointestinal complaints reported infrequently. The open-label extension phase subsequently enrolled 108 patients [20].

A recent study in 28 psoriasis patients treated with DMF (for a minimum of 6 weeks before inclusion in the study) and 32 healthy controls has also reported significantly reduced levels of the faecal S. cerevisiae abundance in psoriasis patients vs. controls (p < 0.001). Following 6–9 weeks of treatment with DMF, levels of S. cerevisiae were restored to levels similar to those of the healthy controls (p = 0.233). Moreover, gastrointestinal side effects as reported in DMF-treated patients were correlated with enhanced S. cerevisiae levels. As S. cerevisiae is known to have beneficial immunomodulatory properties, this may offer a previously uninvestigated means by which DMF elicits its anti-psoriatic effects, i.e. via restoration of an anti-inflammatory microbiome [14].

Clinical head-to-head comparisons of DMF and FAE combination

In 1992, Kolbach and Nieboer [19] examined the efficacy and safety of DMF monotherapy in comparison with the FAE combination over 4 months in a prospective, randomized study in 196 patients with nummular or plaque-type psoriasis (Table 3) [19]. This study had a notable influence on the direction of FAE development in psoriasis over the next two decades. The patients in the DMF group were treated with capsules filled with a semienteric-coated DMF granulate, and in the combination group a DMF/MEF mixture (Fumaderm®) was used. Topical treatment was permitted and consisted of bland cream/ointment or a mild corticosteroid. Patients were evaluated after 3–6, 6–12, 12–18 and 18–24 months. A simplified form of the PSS was used, with > 75% improvement classified as ‘sufficient’, less extensive improvement as ‘deterioration’, and exacerbation as ‘insufficient’.

This trial showed apparent superiority of the FAE mixture over DMF monotherapy. After 24 months, 55% of patients continued on the FAE mixture therapy, while only 16% remained on DMF (p < 0.05). Approximately, 50% of recipients of the FAE mixture showed ‘sufficient’ results over the entire study whereas in the DMF group the proportion of ‘sufficient’ responders declined from 32 to 18% over the 24-month study timeframe. Among responders, the first signs of improvement were generally seen after 3 weeks, with resolution of lesions in the following weeks. Decreased arthralgia severity was noted in 27% of patients treated with DMF and in 50% of patients treated with the FAE mixture. The most prominent reasons for discontinuation of therapy were an ‘insufficient’ result in the DMF group (36%) and AEs in the FAE mixture group (18%). As the authors concluded from their data that the FAE mixture was significantly more effective than DMF alone in the management of psoriasis, subsequent studies tended to focus on combination treatment with FAEs. However, this trial was subject to a number of notable shortcomings. Details of the randomization scheme used were not given, and patients in the FAE mixture group received the equivalent of twice as much DMF as those on DMF monotherapy (up to 480 mg of DMF daily vs. up to 240 mg; Table 3). In addition, a more prolonged dose titration regimen was used in the FAE mixture group (7 weeks involving two tablet strengths, in comparison to 4 weeks with a single strength of DMF), patient demographics were not reported, and dropout rates after 2 years were very high in both arms. Most importantly, the galenical formulation of the FAE mixture differed substantially from the capsules containing a semienteric-coated DMF granulate. As there was no pharmacologic profiling of both formulations, the treatment groups cannot be compared with each other.

More recently, a head-to-head comparator trial has shown a similar clinical response to the licensed FAE mixture (Fumaderm®) and DMF alone, when compared against placebo [32]. This was a phase III randomized and placebo-controlled trial in which patients were assigned to treatment with a new formulation of DMF (LAS41008), the FAE mixture or placebo in a 2:2:1 ratio for 16 weeks in four European countries (Table 3). Patients were followed up for up to 12 months after treatment discontinuation. Notably, uptitration of DMF dosage was the same for DMF and the FAE mixture in this study, and the maximum allowed daily dose was the same in both active therapy groups (720 mg of DMF).

Assessments were based on the European Medicines Agency’s clinical investigation guidance, and consisted of the PASI, Physician’s Global Assessment (PGA; six-point scale) and body surface area involvement (BSA). Primary efficacy endpoints were the proportion of patients achieving PASI 75 (≥ 75% improvement vs. baseline, considered clinically meaningful) and the proportion achieving PGA of 0 or 1 (‘clear’ or ‘almost clear’) at week 16. Other endpoints included BSA, PASI 50 and PASI 90, and primary efficacy endpoints reported at 3 and 8 weeks.

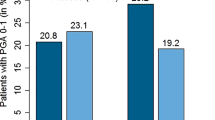

In total, 839 patients were screened and 704 were randomized from 57 study sites (Table 3). Rates of treatment discontinuation were similar in the two active treatment arms (37.1% for DMF and 38.5% for the FAE mixture). The most common reasons for withdrawal were AEs with active treatment (23 and 24%, respectively) and lack of efficacy with placebo (15%). Significantly more patients achieved PASI 75 at week 16 with either DMF or the FAE mixture than with placebo, and DMF alone was non-inferior to the FAE mixture (37.5 vs. 40.3%; p < 0.001; Table 3; Fig. 1). Similar observations were reported for the secondary endpoints of PASI 50 and PASI 90 (Fig. 1). DMF was also non-inferior to the FAE mixture in terms of PGA 0–1 scores. Similar findings were reported for the secondary 3- and 8-week time points. BSA decreased from week 3 onwards in the DMF group, with significance vs. placebo being reported at week 8 and maintained at week 16 (Table 3). Rebound, defined as a worsening of PASI relative to baseline (PASI ≥ 125%) 2 months after the end of treatment, was very infrequent with both active treatments (1.1% with DMF vs. 2.2% with the FAE mixture and 9.3% with placebo). Mean rates of oral dose intake during the trial were very similar for DMF and the FAEs.

(Adapted from Mrowietz et al. [32])

Percentages of patients achieving ≥ 75% improvement in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI 75; primary endpoint) at week 16 in the head-to-head DMF/FAE mixture comparator study [32]. Results are also shown for the secondary endpoints of 50% improvement (PASI 50) and 90% improvement (PASI 90). *p < 0.001 vs. placebo; **p < 0.0001 vs. placebo; †p < 0.001 for noninferiority vs. Fumaderm.

Treatment-emergent AEs were reported in 84% of patients in both active treatment groups, compared with 59.9% of patients receiving placebo (Table 3). Most events (approximately two-thirds in the DMF and the FAE mixture groups and half of those in the placebo group) were of mild severity. Gastrointestinal complaints were most frequent (Table 3) and included diarrhoea, abdominal pain, nausea and flatulence. Flushing was also reported in 18.3 and 16.3% of patients in the DMF and the FAE mixture groups, respectively. Similar incidences of lymphopenia were seen with both active treatments (Table 3).

Overall, the results from this study support a comparable clinical efficacy of DMF monotherapy to the empirical combination of ingredients in the approved FAE combination, when equivalent dosages of DMF are administered. These findings strongly support the assumption that DMF is the major active ingredient in FAE combination products.

Clinical head-to-head comparisons of the FAE combination vs. biologics

There have also been some clinical trials comparing the efficacy of the FAE combination vs. biological agents used to treat psoriasis. A randomized, 24-week open-label trial investigated the efficacy of secukinumab compared with the licensed oral FAE mixture (Fumaderm®) in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis. Significantly more patients achieved PASI 75 in the secukinumab cohort, compared with the FAE cohort (p < 0.001). More patients also achieved a DLQI response of 0–1 with secukinumab, compared with FAEs (p < 0.001) [40]. Another randomized, open-label trial comparing the efficacy and safety of ixekizumab vs. FAEs and methotrexate in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis has recently been completed, but the results are not yet available [13].

Conclusions

FAEs are well established in the management of psoriasis, although clinical trial evidence is limited until today. Nevertheless, FAE therapy has a long history of use and a favourable efficacy/safety profile in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. FAEs are used frequently in Germany and are available and used off-label in a number of other countries [6, 11, 12, 16, 33]. The significance of FAEs in the management of psoriasis is acknowledged by the Cochrane Collaboration [5] and by European and US official guidelines [3, 33, 34].

Accumulating pharmacological and clinical evidence has emphasized that DMF is the main active ingredient in FAE formulations (notably Fumaderm®). Most of its activity appears to be mediated via metabolic conversion to MMF. DMF in fact is a prodrug that, upon oral administration, is rapidly hydrolysed to MMF, the principal active molecule that elicits most of the anti-psoriatic effects [29].

Clinical trials have demonstrated that single DMF therapy is efficacious in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. A recent large-scale phase III randomized and placebo-controlled study has confirmed DMF as the clinically relevant ingredient of the FAE mixture [32]. The efficacy and safety of DMF when used as monotherapy is clinically equivalent to approved FAE mixtures. Therefore, the addition of MEF or other compounds is dispensable.

References

Altmeyer P, Hartwig R, Matthes U (1996) Efficacy and safety profile of fumaric acid esters in oral long-term therapy of severe psoriasis vulgaris. An investigation of 83 patients. Hautarzt 47:190–196

Altmeyer PJ, Matthes U, Pawlak F, Hoffmann K, Frosch PJ, Ruppert P et al (1994) Antipsoriatic effect of fumaric acid derivatives: results of a multicenter double-blind study in 100 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 30:977–981

American Academy of Dermatology Work Group, Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, Feldman SR, Gelfand JM et al (2011) Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Section 6. Guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: case-based presentations and evidence-based conclusions. J Am Acad Dermatol 65:137–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2010.11.055

Arnold DL, Gold R, Kappos L, Bar-Or A, Giovannoni G, Selmaj K et al (2014) Effects of delayed-release dimethyl fumarate on MRI measures in the Phase 3 DEFINE study. J Neurol 261:1794–1802. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-014-7412-x

Atwan A, Ingram JR, Abbott R, Kelson MJ, Pickles T, Bauer A et al (2016) Oral fumaric acid esters for psoriasis: abridged Cochrane systematic review including GRADE assessments. Br J Dermatol 175:873–881. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.14676

Balasubramaniam P, Stevenson O, Berth-Jones J (2004) Fumaric acid esters in severe psoriasis, including experience of use in combination with other systemic modalities. Br J Dermatol 150:741–746. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0007-0963.2004.05739.x

Bayard W, Hunziker T, Krebs A (1987) Fumaric acid derivates in oral long-term treatment of psoriasis. Hautarzt 38:279–285

Biogen Inc (2016) Fachinformation. Fumaderm® initial; Fumaderm®. Biogen. https://www.wuensche.synology.me/Wordpress/wp-content/uploads/Fumarderm.pdf Accessed July 2017

Biogen Inc (2017) TECFIDERA® (dimethyl fumarate) delayed-release capsules, for oral use. Biogen Inc. https://www.tecfidera.com/content/dam/commercial/multiple-sclerosis/tecfidera/pat/en_us/pdf/full-prescribing-info.pdf. Accessed July 2017

Brennan MS, Matos MF, Li B, Hronowski X, Gao B, Juhasz P et al (2015) Dimethyl fumarate and monoethyl fumarate exhibit differential effects on KEAP1, NRF2 activation, and glutathione depletion in vitro. PloS ONE 10:e0120254. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0120254

Burden-Teh E, Lam M, Cohen S (2013) Fumaric acid esters to treat psoriasis: experience in a UK teaching hospital. J Am Acad Dermatol 68(4 Suppl 1):AB52

Carboni I, De Felice C, De Simoni I, Soda R, Chimenti S (2004) Fumaric acid esters in the treatment of psoriasis: an Italian experience. J Dermatolog Treat 15:23–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/09541440042000269

ClinicalTrials.gov (2015) A study of ixekizumab (LY2439821) in participants with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis naive to systemic treatment. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02634801

Eppinga H, Thio HB, Schreurs MWJ, Blakaj B, Tahitu RI, Konstantinov SR et al (2017) Depletion of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in psoriasis patients, restored by Dimethylfumarate therapy (DMF). PloS ONE 12:e0176955. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0176955

European Medicines Agency (2017) Tecfidera: dimethyl fumarate. http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/human/medicines/002601/human_med_001657.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058001d124 Accessed July 2017

Heelan K, Markham T (2012) Fumaric acid esters as a suitable first-line treatment for severe psoriasis: an Irish experience. Clin Exp Dermatol 37:793–795. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2230.2012.04351.x

Hoxtermann S, Nuchel C, Altmeyer P (1998) Fumaric acid esters suppress peripheral CD4- and CD8-positive lymphocytes in psoriasis. Dermatology 196:223–230

Kiehl R, Ionescu G (1992) A defective purine nucleotide synthesis pathway in psoriatic patients. Acta Derm Venereol 72:253–255

Kolbach DN, Nieboer C (1992) Fumaric acid therapy in psoriasis: results and side effects of 2 years of treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol 27:769–771

Langner A, Spellman M (2005) Results of a phase 2 dose-ranging and safety extension study of a novel oral fumarate, BG-12, in patients with severe psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 52:P193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2004.10.783

Lebwohl M (2003) Psoriasis. Lancet 361:1197–1204. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12954-6

Linker RA, Gold R (2013) Dimethyl fumarate for treatment of multiple sclerosis: mechanism of action, effectiveness, and side effects. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 13:394. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-013-0394-8

Linker RA, Lee DH, Stangel M, Gold R (2008) Fumarates for the treatment of multiple sclerosis: potential mechanisms of action and clinical studies. Expert Rev Neurother 8:1683–1690

Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, Feldman SR, Gelfand JM, Gordon KB et al (2009) Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Section 3. Guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol 60:643–659. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2008.12.032

Miller DH, Fox RJ, Phillips JT, Hutchinson M, Havrdova E, Kita M et al (2015) Effects of delayed-release dimethyl fumarate on MRI measures in the phase 3 CONFIRM study. Neurology 84:1145–1152. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000001360

Mrowietz U, Asadullah K (2005) Dimethylfumarate for psoriasis: more than a dietary curiosity. Trends Mol Med 11:43–48

Mrowietz U, Christophers E, Altmeyer P (1998) Treatment of psoriasis with fumaric acid esters: results of a prospective multicentre study. German Multicentre Study. Br J Dermatol 138:456–460

Mrowietz U, Christophers E, Altmeyer P (1999) Treatment of severe psoriasis with fumaric acid esters: scientific background and guidelines for therapeutic use. Br J Dermatol 141:424–429

Mrowietz U, Morrison PJ, Suhrkamp I, Kumanova M, Clement B (2018) The pharmacokinetics of fumaric acid esters reveal their in vivo effects. Trends Pharmacol Sci 39:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tips.2017.11.002

Mrowietz U, Reich K (2013) Case reports of PML in patients treated for psoriasis. N Engl J Med 369:1080–1081. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc1307680#SA1

Mrowietz U, Reich K, Spellman MC (2006) Efficacy, safety, and quality of life effects of a novel oral formulation of dimethyl fumarate in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: results of a phase 3 study. J Am Acad Dermatol 54(Suppl 3):AB198–AB203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2005.11.831

Mrowietz U, Szepietowski JC, Loewe R, van de Kerkhof P, Lamarca R, Ocker WG et al (2017) Efficacy and safety of LAS41008 (dimethyl fumarate) in adults with moderate-to-severe chronic plaque psoriasis: a randomized, double-blind, Fumaderm(R)—and placebo-controlled trial (BRIDGE). Br J Dermatol 176:615–623. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.14947

Nast A, Gisondi P, Ormerod AD, Saiag P, Smith C, Spuls PI et al (2015) European S3-Guidelines on the systemic treatment of psoriasis vulgaris–Update 2015–Short version–EDF in cooperation with EADV and IPC. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 29:2277–2294. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.13354

National Clinical Guideline Centre (UK) (2012) Psoriasis: assessment and management. Clinical Guidance. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg153/resources/psoriasis-assessment-and-management-pdf-35109629621701. Accessed July 2017

Netherlands pharmacovigilance centre (2015) Dimethyl fumarate and progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy (PML). http://databankws.lareb.nl/Downloads/KWB_2015_1_Dimethylfum.pdf. Accessed Jan 2018

Nieboer C, de Hoop D, Langendijk PN, van Loenen AC, Gubbels J (1990) Fumaric acid therapy in psoriasis: a double-blind comparison between fumaric acid compound therapy and monotherapy with dimethylfumaric acid ester. Dermatologica 181:33–37

Nieboer C, de Hoop D, van Loenen AC, Langendijk PN, van Dijk E (1989) Systemic therapy with fumaric acid derivates: new possibilities in the treatment of psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 20:601–608

Pathirana D, Ormerod AD, Saiag P, Smith C, Spuls PI, Nast A et al. (2009) European S3-guidelines on the systemic treatment of psoriasis vulgaris. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 23(Suppl 2):1–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03389.x

Schweckendiek W (1959) Treatment of psoriasis vulgaris. Medizinische Monatsschrift 13:103–104

Sticherling M, Mrowietz U, Augustin M, Thaci D, Melzer N, Hentschke C et al (2017) Secukinumab is superior to fumaric acid esters in treating patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis who are naive to systemic treatments: results from the randomized controlled PRIME trial. Br J Dermatol 177:1024–1032. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.15707

Walker F, Adamczyk A, Kellerer C, Belge K, Bruck J, Berner T et al (2014) Fumaderm(R) in daily practice for psoriasis: dosing, efficacy and quality of life. Br J Dermatol 171:1197–1205. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.13098

Zweegers J, De Jong EM, Nijsten T, de Bes J, te Booij M, Borgonjen RJ et al (2014) Summary of the Dutch S3-Guidelines on the treatment of psoriasis 2011. Dermatol Online J 20(3):1

Related articles recently published in Archives of Dermatological Research (selected by the journal’s editorial staff)

Augustin M, Eissing L, Langenbruch A, Enk A, Luger T, Maassen D, Mrowietz U, Reich K, Reusch M, Stromer K, Thaci D, von Kiedrowski R, Radtke MA (2016) The German National Program on Psoriasis Health Care 2005–2015: results and experiences. Arch Dermatol Res 308:389–400

Florek AG, Wang CJ, Armstrong AW (2018) Treatment preferences and treatment satisfaction among psoriasis patients: a systematic review. Arch Dermatol Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-018-1808-x

Ottas A, Fishman D, Okas TL, Kingo K, Soomets U (2017) The metabolic analysis of psoriasis identifies the associated metabolites while providing computational models for the monitoring of the disease. Arch Dermatol Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-017-1760-1

Poor AK, Brodszky V, Pentek M, Gulacsi L, Ruzsa G, Hidvegi B, Hollo P, Karpati S, Sardy M, Rencz F (2018) Is the DLQI appropriate for medical decision-making in psoriasis patients? Arch Dermatol Res 310:47–55

Sinclair R, Turner GA, Jones DA, Luo S (2016) Clinical studies in dermatology require a post-treatment observation phase to define the impact of the intervention on the natural history of the complaint. Arch Dermatol Res 308:379–387

Funding

Medical writing assistance was provided by Sandra Cuscó PhD of Bioscript Group, Macclesfield, UK and funded by Almirall S.A.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

LL has no conflicts of interest to declare. KA is a stock holder and former employee of Bayer AG and has received financial support and/or served as consultant, advisory board member, or speaker for AbbVie, Antabio, Almirall, EmertiPharma, Galderma, Leo, Loreal, Eli Lilly, and Novartis. IPC and AA are employees of Almirall S.A. UM has been an advisor and/or received speakers honoraria and/or received grants and/or participated in clinical trials of the following companies: AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Biogen, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Celgene, Dr. Reddy’s, Eli Lilly, Foamix, Formycon, Forward Pharma, Janssen, Leo Pharma, Medac, MSD, Novartis, VBL and Xenoport.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Landeck, L., Asadullah, K., Amasuno, A. et al. Dimethyl fumarate (DMF) vs. monoethyl fumarate (MEF) salts for the treatment of plaque psoriasis: a review of clinical data. Arch Dermatol Res 310, 475–483 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-018-1825-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-018-1825-9