Abstract

Introduction

In recent years, there has been an increasing demand for patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) to assess the outcome following orthopedic surgery. But, we are lacking a standard set of PROMs to assess the outcome of hallux valgus surgery. The aim of this study was to analyze the chosen patient rated outcome scores used in studies reporting on hallux valgus surgery.

Materials and methods

The study was based on a previously published living systematic review. Included were prospective, comparative studies of different surgical procedures or the same procedure for different degrees of deformity. Four common databases were searched for the last decade. Study selection, data extraction, and risk of bias assessment were made by two independent reviewers. Data assessed were the individual PROMs used to assess the outcome of hallux valgus surgery.

Results

46 studies (30 RCTs and 16 non-randomized prospective studies) met the inclusion criteria. The most commonly used clinical outcome measures were the AOFAS (55%) and the VAS (30%). No differences were found between frequency of the individual scores per the level of evidence or the type of osteotomy.

Conclusion

Based on a systematic literature review, the AOFAS and VAS are the most frequently used outcome tools in studies assessing the outcome following hallux valgus surgery. Based on the literature available, the MOXFQ is a more valid alternative.

Level of evidence

Level I; systematic review of prospective comparative (level II) and randomized controlled trials (level I).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Assessing the outcome following orthopedic surgery remains a hot topic of debate. In general, the outcome is frequently assessed by imaging, range of motion (ROM), or patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). In recent years, there has been an increasing demand for PROMs, both from scientific committees and governments. This stays especially true for elective foot and ankle surgery, as it has to show its efficacy to both, the patient and the insurance provider.

In a previously published living systematic review, the authors assessed the outcome following hallux valgus surgery [1]. Despite a considerable number of eligible studies, all of which had a level of evidence of I or II, a meta-analysis could only be conducted for the HVA, IMA, and AOFAS. This dramatically highlights the grossly missing standardization of study protocols in foot and ankle surgery. In the initial study, the authors did not conduct a formal analysis of all the PROMs assessed in the different studies.

Therefore, the aim of the current study was to reanalyze the studies included in the living systematic review per the chosen patient rated outcome scores. The results were discussed to identify a possible standard set of outcome measures for hallux valgus outcome research.

Materials and methods

Study selection and data extraction

The study was based on a previously published living systematic review and is part of the current revision process of the German guidelines for hallux valgus surgery (033-018). The review was registered a priori (Prospero #CRD42021261490), conducted per the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA-P) guidelines [2] and the PICOS criteria [3]. Four common databases (Medline (PubMed), Scopus, Central and EMBASE) and the grey literature were searched from 01/01/2012 to 01/31/2023. Prospective studies comparing either two surgical procedures or one surgical procedure for different stages of hallux valgus deformity were included. The whole study selection-, data extraction- and assessment-process was conducted by two independent reviewers (SE, SFB). Disagreement at any stage was resolved by discussion with a third reviewer (HP).

Data assessment

The level of evidence was rated per the recommendations of Wright et al. [4] and risk of bias was assessed by the Risk of Bias 2 (RoB 2) tool [5] or the Newcastle–Ottawa scale [6], where appropriate. The primary outcome parameter assessed was the PROMs used in each individual study. PROMs included the visual analog scale for pain (VAS), clinician-based outcome scores, and any quality-of-life (QOL) score. These were analyzed descriptively per their frequency, the level of evidence [4], the type of osteotomy performed, and the quality of the journal (i.e. impact factor) in which the study was published.

Results

Study selection

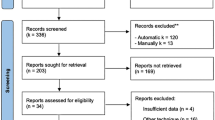

Figure 1 depicts the study selection process. 3022 studies were screened for title and abstract and 378 for full-text. Finally, 46 primary studies [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52] were enrolled for qualitative analysis consisting of 40 studies comparing different surgical procedures [7, 9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20, 22,23,24,25,26, 28, 30,31,32,33, 35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42, 44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52] and six studies comparing the same surgical procedure for different severities of HV deformity [8, 21, 27, 29, 34, 43]. 30 studies were RCTs (RoB2: 2 × high risk, 28 moderate risk) and 16 non-randomized comparative studies (Newcastle–Ottawa-Scale: 6 ± 1 points ≙ moderate risk).

Overall, only eight different outcome measures were used in the studies. The individual PROMs per the studies’ level of evidence, in descending order, and per the surgical technique are outened in Table 1. The two most used clinical outcome measures were the AOFAS (55%) and the VAS (30%). The remaining six PROMs were used in less than 5% of the studies each. No correlation could be found between the frequency of the individual scores and the level of evidence or the type of osteotomy. Also, the usage of PROMs per the various journals and the corresponding impact factors of the publishing journals did not differ (Table 2).

Discussion

The AOFAS and VAS scores were the most frequently applied assessments to rate the outcome in hallux valgus surgery for the past eleven years. This result was independent of the studies’ level of evidence, the type of surgery performed, or the impact factor of the journal in which the study was published.

The current study is part of the revision process of the German Hallux Valgus guideline. The authors’ intention was to define a standard set of PROMs to evaluate the patient-rated outcome of hallux valgus surgery. This set of scores should be valid and allow a comparison to current literature. Our approach was to re-analyze the studies identified in a previously published living systematic review which included prospective studies, published after 2012, comparing either two surgical procedures or one surgical procedure for different stages of hallux valgus deformity. Consequently, the analyzed data set could have a selection bias. Still, only higher quality studies were included and one could assume, that these studies spend the most time on properly designing the methodology used. Although eight different scores were used, the by far most frequently assessed ones were the AOFAS and VAS. The VAS was scored on a ten-item Likert scale in all cases.

Throughout foot and ankle literature, the AOFAS Clinical Rating Systems [53] are the most commonly used outcome score. This stayed true for the current analysis on studies on hallux valgus surgery. Due to the fact that this study is a component of the revision of the German Hallux Valgus guidelines, one limitation of our study is that only studies published after 2012 were included. The large number of studies included, however, enables for further interpretation of the state of the art of PROMs used in hallux valgus surgery outcome studies.

Although the AOFAS remain the top dog, they have been criticized for several reasons. First, the AOFAS are not PROMs, as they combine a patient rated and clinician rated section. They are clinician-based outcome measures, which evaluate patients’ pain, function, and alignment based upon clinicians’ observations. They therefore do not eliminate a possible observer bias [54]. Subsequent studies demonstrated their limitations and the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society does not endorse the scales due to insufficient reliability and validity [55]. Guyton et al. [56] conducted a Monte Carlo computer modelling technique to assess limitations of the AOFAS scoring system. They simulated for each item the responses of different, idealized patient populations. The two major points of concern per the reliability of the AOFAS score were: the scoring items are used as absolute descriptors (e.g. “no limitation” or “no pain”) and are therefore susceptible for an interpretation bias by both, patients and clinicians; the limited number of response intervals leads to a pronounced floor- and/or ceiling effect [56, 57]. Furthermore, the AOFAS overemphasis the symptoms pain, equaling a maximum of 40 points, resulting in inferior outcome measures concerning other symptoms like stiffness or deformity [58]. Finally, the MCID is less for older patients compared to younger patients, and those patients with middle-range disability generally have less MCID values compared to those with minimal or severe disability [59]. Use of the AOFAS Clinical Rating Systems as the sole instrument is therefore discouraged [55].

Due to these limitations, the foot and ankle community, should strive to establish a new standard to assess patient rated outcomes, not only in hallux valgus surgery. There are more than 89 assessment tools available which measure overall foot and ankle function, overall health, or are designed for specific diagnoses and procedures.

General quality of life outcomes scores or pain scores are not enough to evaluate a hallux valgus population. Other measures have been developed and tested for a wide variety of pathologies in foot and ankle surgery (FFI, FAAM, AAOS, FHSQ and others). Furthermore, a disease-specific outcome measure is necessary to assess outcomes. MOXFQ, SEFAS and FAOS have been evaluated for hallux valgus surgery.

The FAOS [60] consisting of five subscales, with 42 items was derived from the Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome score (KOOS) [61]. It was validated on patients with general foot and ankle disorders first, then on patients with hallux valgus deformity [54]. It showed acceptable validity, reliability, responsiveness, and comparability to the SF-36 in four out of five subscales [54]. The sports and recreation subscale showed little responsiveness to hallux valgus surgery and ceiling effects were present for the activities of the daily living and sports scale. The symptoms subscale showed a low correlation to the SF-36 due to the foot-specific items assessed in the FAOS [54].

The SEFAS consisting of 12 items, with 3 subscales was developed for assessing ankle replacement surgery but has been tested on a hallux valgus population with good psychometric properties [62]. It presented good validity, reliability, and responsiveness with a lack of MCID data.

The MOXFQ, consisting of 16 items with 3 domains, has been validated for foot and ankle disorders in general and specifically for a hallux valgus population. It has been extensively tested and was more sensitive than general health measures for quantifying hallux valgus surgery [63, 64].It has been compared to other outcome measures with good results. Comparison of the MOXFQ and the SEFAS demonstrated good psychometric properties with excellent test–retest reliability and internal consistency for both scores with superior responsiveness for the MOXFQ [65]. The MOXFQ showed higher responsiveness to detect changes over time or after surgery and has been translated and evaluated in more languages than SEFAS [65].

Recently the EFAS score has been validated in a population of hallux valgus patients with a short follow-up time of 6 months [66]. It has been tested with fair construct validity and reliability. However, responsiveness has not been evaluated at all. Further validation and comparative studies are necessary to rate the EFAS score in comparison to the above-mentioned PROMs.

Based on these considerations, it is even more surprising, that the vast majority of authors still relies on the AOFAS as their primary outcome score. Only three studies assessed the MOXFQ and no studies the SEFAS or EFAS score. The expert panel revising the German guidelines for hallux valgus surgery therefore recommends the use of the MOXFQ as the primary outcome score, due to its higher responsiveness and availability in more languages. There is a strong recommendation to also assess the VAS (10-item Likert scale). The use of the EFAS will be reconsidered in the next guideline revision. The AOFAS should only be assessed as a secondary outcome parameter to allow a higher comparability between the different studies.

Conclusion

Based on a systematic literature review, the AOFAS and VAS are the most frequently used outcome tools in studies assessing the outcome following hallux valgus surgery. Based on the literature available, the MOXFQ is a more valid alternative.

References

Ettinger S, Spindler FT, Savli M, committee DAFs, Baumbach SF (2023) Correction potential and outcome of various surgical procedures for hallux valgus surgery – a living systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg (under review). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-024-05521-0

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD et al (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed) 74(9):790–799. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rec.2021.07.010

da Costa Santos CM, de Mattos Pimenta CA, Nobre MR (2007) The PICO strategy for the research question construction and evidence search. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem 15(3):508–511. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0104-11692007000300023

Wright JG, Swiontkowski MF, Heckman JD (2003) Introducing levels of evidence to the journal. J Bone Joint Surg Am 85(1):1–3

Sterne JAC, Savovic J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I et al (2019) RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 366:l4898. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l4898

Wells GA, Wells G, Shea B, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J et al (eds) (2014) The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses

Avcu B, Akalin Y, Cevik N, Öztürk A, Sahin N, Öztas S et al (2017) Scarf osteotomy or Mau osteotomy for correction of moderate to severe hallux valgus deformity: a prospective, randomized study. Eur Res J 4(1):6–15. https://doi.org/10.18621/eurj.302186

Biz C, Fosser M, Dalmau-Pastor M, Corradin M, Roda MG, Aldegheri R et al (2016) Functional and radiographic outcomes of hallux valgus correction by mini-invasive surgery with Reverdin-Isham and Akin percutaneous osteotomies: a longitudinal prospective study with a 48-month follow-up. J Orthop Surg Res 11(1):157. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-016-0491-x

Boychenko AV, Solomin LN, Belokrylova MS, Tyulkin EO, Davidov DV, Krutko DM (2019) Hallux valgus correction with rotational scarf combined with adductor hallucis tendon transposition. J Foot Ankle Surg 58(1):34–37. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jfas.2018.07.012

Buciuto R (2014) Prospective randomized study of chevron osteotomy versus Mitchell’s osteotomy in hallux valgus. Foot Ankle Int 35(12):1268–1276. https://doi.org/10.1177/1071100714550647

Choi JY, Kim BH, Suh JS (2021) A prospective study to compare the operative outcomes of minimally invasive proximal and distal chevron metatarsal osteotomy for moderate-to-severe hallux valgus deformity. Int Orthop 45(11):2933–2943. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-021-05106-1

Di Giorgio L, Sodano L, Touloupakis G, De Meo D, Marcellini L (2016) Reverdin-Isham osteotomy versus Endolog system for correction of moderate hallux valgus deformity: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Ter 167(6):e150–e154. https://doi.org/10.7417/CT.2016.1960

Dragosloveanu S, Popov VM, Cotor DC, Dragosloveanu C, Stoica CI (2022) Percutaneous chevron osteotomy: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Medicina (Kaunas) 58(3):359. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina58030359

Elshazly O, Abdel Rahman AF, Fahmy H, Sobhy MH, Abdelhadi W (2019) Scarf versus long chevron osteotomies for the treatment of hallux valgus: a prospective randomized controlled study. Foot Ankle Surg 25(4):469–477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fas.2018.02.017

Faber FW, Mulder PG, Verhaar JA (2004) Role of first ray hypermobility in the outcome of the Hohmann and the Lapidus procedure. A prospective, randomized trial involving one hundred and one feet. J Bone Joint Surg Am 86(3):486–495. https://doi.org/10.2106/00004623-200403000-00005

Faber FW, van Kampen PM, Bloembergen MW (2013) Long-term results of the Hohmann and Lapidus procedure for the correction of hallux valgus: a prospective, randomised trial with eight- to 11-year follow-up involving 101 feet. Bone Joint J 95-B(9):1222–1226. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.95B9.31560

Frigg A, Zaugg S, Maquieira G, Pellegrino A (2019) Stiffness and range of motion after minimally invasive chevron-akin and open scarf-akin procedures. Foot Ankle Int 40(5):515–525. https://doi.org/10.1177/1071100718818577

Giannini S, Cavallo M, Faldini C, Luciani D, Vannini F (2013) The SERI distal metatarsal osteotomy and Scarf osteotomy provide similar correction of hallux valgus. Clin Orthop Relat Res 471(7):2305–2311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-013-2912-z

Glazebrook M, Copithorne P, Boyd G, Daniels T, Lalonde KA, Francis P et al (2014) Proximal opening wedge osteotomy with wedge-plate fixation compared with proximal chevron osteotomy for the treatment of hallux valgus: a prospective, randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 96(19):1585–1592. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.M.00231

Gutteck N, Wohlrab D, Zeh A, Radetzki F, Delank KS, Lebek S (2013) Comparative study of Lapidus bunionectomy using different osteosynthesis methods. Foot Ankle Surg 19(4):218–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fas.2013.05.002

Hofstaetter SG, Schuh R, Trieb K, Trnka HJ (2012) Modified chevron osteotomy with lateral release and screw fixation for treatment of severe hallux deformity. Z Orthop Unfall 150(6):594–600. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0032-1327933

Jeuken RM, Schotanus MG, Kort NP, Deenik A, Jong B, Hendrickx RP (2016) Long-term follow-up of a randomized controlled trial comparing scarf to chevron osteotomy in hallux valgus correction. Foot Ankle Int 37(7):687–695. https://doi.org/10.1177/1071100716639574

Jowett CRJ, Bedi HS (2017) Preliminary results and learning curve of the minimally invasive chevron akin operation for hallux valgus. J Foot Ankle Surg 56(3):445–452. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jfas.2017.01.002

Kaufmann G, Dammerer D, Heyenbrock F, Braito M, Moertlbauer L, Liebensteiner M (2019) Minimally invasive versus open chevron osteotomy for hallux valgus correction: a randomized controlled trial. Int Orthop 43(2):343–350. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-018-4006-8

Kaufmann G, Mortlbauer L, Hofer-Picout P, Dammerer D, Ban M, Liebensteiner M (2020) Five-year follow-up of minimally invasive distal metatarsal chevron osteotomy in comparison with the open technique: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 102(10):873–879. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.19.00981

Kaufmann G, Weiskopf D, Liebensteiner M, Ulmer H, Braito M, Endstrasser F et al (2021) Midterm results following minimally invasive distal chevron osteotomy: comparison with the minimally invasive Reverdin-Isham osteotomy by means of meta-analysis. In Vivo 35(4):2187–2196. https://doi.org/10.21873/invivo.12490

Kiyak G, Esemenli T (2019) Should we use intermetatarsal angle as primary determinant to define the limits of distal chevron osteotomy? J Foot Ankle Surg 58(5):880–885. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jfas.2018.12.031

Klemola T, Leppilahti J, Laine V, Pentikainen I, Ojala R, Ohtonen P et al (2017) Effect of first tarsometatarsal joint derotational arthrodesis on first ray dynamic stability compared to distal chevron osteotomy. Foot Ankle Int 38(8):847–854. https://doi.org/10.1177/1071100717706153

Lamo-Espinosa JM, Flórez B, Villas C, Pons-Villanueva J, Bondía JM, Aquerreta JD et al (2015) The relationship between the sesamoid complex and the first metatarsal after hallux valgus surgery without lateral soft-tissue release: a prospective study. J Foot Ankle Surg 54(6):1111–1115. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jfas.2015.07.022

Lechler P, Feldmann C, Köck FX, Schaumburger J, Grifka J, Handel M (2012) Clinical outcome after Chevron-Akin double osteotomy versus isolated Chevron procedure: a prospective matched group analysis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 132(1):9–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-011-1385-3

Lee KB, Cho NY, Park HW, Seon JK, Lee SH (2015) A comparison of proximal and distal Chevron osteotomy, both with lateral soft-tissue release, for moderate to severe hallux valgus in patients undergoing simultaneous bilateral correction: a prospective randomised controlled trial. Bone Joint J 97-B(2):202–207. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.97B2.34449

Lee M, Walsh J, Smith MM, Ling J, Wines A, Lam P (2017) Hallux valgus correction comparing percutaneous chevron/akin (PECA) and open scarf/akin osteotomies. Foot Ankle Int 38(8):838–846. https://doi.org/10.1177/1071100717704941

Ling SKK, Wu YM, Li C, Lui TH, Yung PS (2020) Randomised control trial on the optimal duration of non-weight-bearing walking after hallux valgus surgery. J Orthop Translat 23:61–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jot.2020.04.009

Loh B, Chen JY, Yew AK, Chong HC, Yeo MG, Tao P et al (2015) Prevalence of metatarsus adductus in symptomatic hallux valgus and its influence on functional outcome. Foot Ankle Int 36(11):1316–1321. https://doi.org/10.1177/1071100715595618

Mahadevan D, Lines S, Hepple S, Winson I, Harries W (2016) Extended plantar limb (modified) chevron osteotomy versus scarf osteotomy for hallux valgus correction: a randomised controlled trial. Foot Ankle Surg 22(2):109–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fas.2015.05.012

Matricali GA, Vermeersch G, Busschots E, Fieuws S, Deschamps K (2014) Prospective randomized comparative study on V-Y and pants-over-vest capsulorraphy in chevron and scarf osteotomy. Acta Orthop Belg 80(2):280–287

Milczarek M, Nowak K, Tomasik B, Milczarek J, Laganowski P, Domzalski M (2021) Additional akin proximal phalanx procedure has a limited effect on the outcome of scarf osteotomy for hallux valgus surgery. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. https://doi.org/10.7547/20-071

Mosca M, Russo A, Caravelli S, Massimi S, Vocale E, Grassi A et al (2021) Piezoelectric tools versus traditional oscillating saw for distal linear osteotomy in hallux valgus correction: triple-blinded, randomized controlled study. Foot Ankle Surg. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fas.2021.03.024

Palmanovich E, Ohana N, David S, Small I, Hetsroni I, Amar E et al (2021) Distal chevron osteotomy vs the simple, effective, rapid, inexpensive technique (SERI) for mild to moderate isolated hallux valgus: a randomized controlled study. Indian J Orthop 55(Suppl 1):110–118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43465-020-00209-0

Park HW, Lee KB, Chung JY, Kim MS (2013) Comparison of outcomes between proximal and distal chevron osteotomy, both with supplementary lateral soft-tissue release, for severe hallux valgus deformity: a prospective randomised controlled trial. Bone Joint J 95-B(4):510–516. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.95B4.30464

Park YB, Lee KB, Kim SK, Seon JK, Lee JY (2013) Comparison of distal soft-tissue procedures combined with a distal chevron osteotomy for moderate to severe hallux valgus: first web-space versus transarticular approach. J Bone Joint Surg Am 95(21):e158. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.L.01017

Patel S, Garg P, Fazal MA, Shahid MS, Park DH, Ray PS (2019) A comparison of two designs of postoperative shoe on function, satisfaction, and back pain after hallux valgus surgery. Foot Ankle Spec 12(3):228–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/1938640018782608

Pentikainen I, Ojala R, Ohtonen P, Piippo J, Leppilahti J (2014) Preoperative radiological factors correlated to long-term recurrence of hallux valgus following distal chevron osteotomy. Foot Ankle Int 35(12):1262–1267. https://doi.org/10.1177/1071100714548703

Pentikainen I, Piippo J, Ohtonen P, Junila J, Leppilahti J (2015) Role of fixation and postoperative regimens in the long-term outcomes of distal chevron osteotomy: a randomized controlled two-by-two factorial trial of 100 patients. J Foot Ankle Surg 54(3):356–360. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jfas.2014.08.001

Puchner SE, Trnka HJ, Willegger M, Staats K, Holinka J, Windhager R et al (2018) Comparison of plantar pressure distribution and functional outcome after scarf and austin osteotomy. Orthop Surg 10(3):255–263. https://doi.org/10.1111/os.12400

Radwan YA, Mansour AM (2012) Percutaneous distal metatarsal osteotomy versus distal chevron osteotomy for correction of mild-to-moderate hallux valgus deformity. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 132(11):1539–1546. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-012-1585-5

Sahin N, Cansabuncu G, Cevik N, Turker O, Ozkaya G, Ozkan Y (2018) A randomized comparison of the proximal crescentic osteotomy and rotational scarf osteotomy in the treatment of hallux valgus. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc 52(4):261–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aott.2018.02.008

Saxena A, St Louis M (2013) Medial locking plate versus screw fixation for fixation of the Ludloff osteotomy. J Foot Ankle Surg 52(2):153–157. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jfas.2012.11.005

Torrent J, Baduell A, Vega J, Malagelada F, Luna R, Rabat E (2021) Open vs minimally invasive scarf osteotomy for hallux valgus correction: a randomized controlled trial. Foot Ankle Int 42(8):982–993. https://doi.org/10.1177/10711007211003565

Uygur E, Ozkan NK, Akan K, Cift H (2016) A comparison of Chevron and Lindgren-Turan osteotomy techniques in hallux valgus surgery: a prospective randomized controlled study. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc 50(3):255–261. https://doi.org/10.3944/AOTT.2016.14.0272

Wester JU, Hamborg-Petersen E, Herold N, Hansen PB, Froekjaer J (2016) Open wedge metatarsal osteotomy versus crescentic osteotomy to correct severe hallux valgus deformity—a prospective comparative study. Foot Ankle Surg 22(1):26–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fas.2015.04.006

Windhagen H, Radtke K, Weizbauer A, Diekmann J, Noll Y, Kreimeyer U et al (2013) Biodegradable magnesium-based screw clinically equivalent to titanium screw in hallux valgus surgery: short term results of the first prospective, randomized, controlled clinical pilot study. BioMed Cent. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-925X-12-62

Kitaoka HB, Alexander IJ, Adelaar RS, Nunley JA, Myerson MS, Sanders M (1994) Clinical rating systems for the ankle-hindfoot, midfoot, hallux, and lesser toes. Foot Ankle Int 15(7):349–353. https://doi.org/10.1177/107110079401500701

Chen L, Lyman S, Do H, Karlsson J, Adam SP, Young E et al (2012) Validation of foot and ankle outcome score for hallux valgus. Foot Ankle Int 33(12):1145–1155. https://doi.org/10.3113/FAI.2012.1145

Pinsker E, Daniels TR (2011) AOFAS position statement regarding the future of the AOFAS clinical rating systems. Foot Ankle Int 32(9):841–842. https://doi.org/10.3113/FAI.2011.0841

Guyton GP (2001) Theoretical limitations of the AOFAS scoring systems: an analysis using Monte Carlo modeling. Foot Ankle Int 22(10):779–787. https://doi.org/10.1177/107110070102201003

Van Lieshout EM, De Boer AS, Meuffels DE, Den Hoed PT, Van der Vlies CH, Tuinebreijer WE et al (2017) American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS) Ankle-Hindfoot Score: a study protocol for the translation and validation of the Dutch language version. BMJ Open 7(2):e012884. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012884

SooHoo NF, Shuler M, Fleming LL, American Orthopaedic F, Ankle S (2003) Evaluation of the validity of the AOFAS clinical rating systems by correlation to the SF-36. Foot Ankle Int 24(1):50–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/107110070302400108

Sutherland JM, Albanese CM, Wing K, Zhang YJ, Younger A, Veljkovic A et al (2021) Effect of patient demographics on minimally important difference of ankle osteoarthritis scale among end-stage ankle arthritis patients. Foot Ankle Int 42(5):624–632. https://doi.org/10.1177/1071100720977842

Roos EM, Brandsson S, Karlsson J (2001) Validation of the foot and ankle outcome score for ankle ligament reconstruction. Foot Ankle Int 22(10):788–794. https://doi.org/10.1177/107110070102201004

Roos EM, Roos HP, Lohmander LS, Ekdahl C, Beynnon BD (1998) Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS)—development of a self-administered outcome measure. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 28(2):88–96. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.1998.28.2.88

Coster MC, Bremander A, Rosengren BE, Magnusson H, Carlsson A, Karlsson MK (2014) Validity, reliability, and responsiveness of the Self-reported Foot and Ankle Score (SEFAS) in forefoot, hindfoot, and ankle disorders. Acta Orthop 85(2):187–194. https://doi.org/10.3109/17453674.2014.889979

Dawson J, Boller I, Doll H, Lavis G, Sharp R, Cooke P et al (2011) The MOXFQ patient-reported questionnaire: assessment of data quality, reliability and validity in relation to foot and ankle surgery. Foot (Edinb) 21(2):92–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foot.2011.02.002

Dawson J, Coffey J, Doll H, Lavis G, Cooke P, Herron M et al (2006) A patient-based questionnaire to assess outcomes of foot surgery: validation in the context of surgery for hallux valgus. Qual Life Res 15(7):1211–1222. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-006-0061-5

Arbab D, Kuhlmann K, Schnurr C, Luring C, Konig D, Bouillon B (2019) Comparison of the Manchester-Oxford Foot Questionnaire (MOXFQ) and the Self-Reported Foot and Ankle Outcome Score (SEFAS) in patients with foot or ankle surgery. Foot Ankle Surg 25(3):361–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fas.2018.01.003

Tan CC, Sayampanathan AA, Kwan YH, Yeo W, Yeo NEM (2023) Validity and reliability of the European Foot and Ankle Society (EFAS) score in patients with hallux valgus in Singapore. J Foot Ankle Surg 62(2):295–299. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jfas.2022.08.003

Acknowledgements

D.A.F. scientific committee: Prof. Dr. Christina Stukenborg-Colsman, MD (christina.stukenborg@diakovere.de); Prof. Dr. Sabine Ochman, MD (sabine.ochman@ukmuenster.de); Prof. Dr. Stefan Rammelt, MD (Stefan.rammelt@uniklinikum-dresden.de); Prof. Dr. Hans Polzer, MD (hans.polzer@med.uni-muenchen.de); Prof. Dr. Natalia Gutteck, MD (natalia.gutteck@uk-halle.de); PD Dr. Norbert Harrasser, MD (norbert.harrasser@atos.de); PD Dr. med. Christian Plaaß, MD (Christian.plaas@diakovere.de)

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

The study idea was consented in the whole study group during the course of a living systematic review for the German guidelines for hallux valgus treatment. SFT, ES and BSF were responsible for the study design and conception. BSF and SFT were responsible for the manuscript preparation. SFT and BSF conducted the review and data extraction. AD was responsible for data interpretation. The whole study group participated in the data interpretation, paper conception and proof reading.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at http://www.icmje.org/disclosure-of-interest/ and declare: all authors had no financial support for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Spindler, F.T., Ettinger, S., Arbab, D. et al. Patient-reported outcome measures in studies on hallux valgus surgery: what should be assessed. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-024-05523-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-024-05523-y