Abstract

Background

Implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) are designed to deliver shocks in the event of ventricular arrhythmias. Some ICD recipients experience the sensation of ICD discharge in the absence of an actual discharge (phantom shock, PS).

Objectives

The aim of this study was to evaluate the incidence, predictors, and consequences of PS in ICD recipients.

Materials and methods

Consecutive ICD recipients were examined during a routine outpatient follow-up (FU) visit. Subjects completed a written survey; their level of depression and anxiety was assessed with the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS). Quality of life (QOL) was assessed using the Minnesota living with heart failure questionnaire.

Results

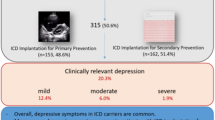

Of 434 patients invited to the study, 423 (97.5%) ICD recipients agreed to and completed the survey; 349 (83%) had a primary prevention indication and 339 (80%) ischemic cardiomyopathy. A total of 27 patients (6.4%) reported a PS during a mean FU of 64 ± 44 months (5.4% in the primary prevention group and 10.8% in the secondary prevention group; p = 0.11). PS were related to higher education (≥bachelor’s degree 41% versus 20%; p = 0.03), and more frequent in patients receiving adequate shocks during FU (34% versus 0.5%; p < 0.001). HADS score levels were higher following PS (15 ± 6 versus 8.8 ± 7.4; p < 0.001). The majority of patients reporting PS felt that the information provided to them prior to ICD placement was insufficient (22.2% versus 5.0%), that they needed psychological support after ICD implantation (26% versus 3%), and considered ICD deactivation in near end-of-life situations (59% versus 29%; p < 0.001 for all).

Conclusions

PS occur in 6.4% of all ICD recipients and are related to higher education and to patients that experienced adequate shocks during FU.

Zusammenfassung

Hintergrund

Implantierbare Kardioverter-Defibrillatoren (ICD) wurden entwickelt, um bei ventrikulären Arrhythmien Schocks abzugeben. Einige Patienten mit ICD empfinden subjektiv eine solche Schockabgabe, ohne dass diese tatsächlich stattgefunden hat (Phantomschock [PS]).

Fragestellung

Ziel der Untersuchung war es, die Inzidenz, Prädiktoren und Folgen von PS bei Patienten mit ICD zu analysieren.

Material und Methoden

Konsekutive ICD-Patienten der Device-Ambulanz wurden eingeschlossen und im Rahmen eines routinemäßigen Follow-up(FU)-Termins untersucht. Die Patienten füllten einen Fragebogen aus, ihr Depressions- und Angstlevel wurde mithilfe der Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) untersucht. Die Lebensqualität wurde mithilfe des Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire evaluiert.

Ergebnisse

Von den 434 eingeladenen Patienten waren 423 (97,5 %) zur Teilnahme bereit. Bei 349 (83 %) war Primärprophylaxe die ICD-Indikation, 339 (80 %) hatten eine ischämische Kardiomyopathie. 27 Patienten (6,4 %) berichteten einen PS während des mittleren FU von 64 ± 44 Monaten (5,4 % in der primärpräventiven und 10,8 % in der sekundärpräventiven Gruppe; p = 0,11). PS waren mit einem höheren Bildungsniveau assoziiert (≥ Bachelorabschluss 41 % vs. 20 %; p = 0,03) und traten häufiger bei Patienten mit adäquaten Schocks im Laufe des FU auf (34 % vs. 0,5 %; p < 0,001). HADS-Score-Werte waren signifikant höher nach PS (15 ± 6 vs. 8,8 ± 7,4; p < 0,001). Patienten mit PS waren häufiger mit den präoperativen Informationen unzufrieden (22,2 % vs. 5,0 %), benötigten häufiger psychologische Betreuung (26 % vs. 3 %) und zogen häufiger eine ICD-Deaktivierung am Lebensende in Betracht (59 % vs. 29 %; p < 0,001 für alle).

Zusammenfassung

PS treten bei 6,4 % aller Patienten mit ICD auf und hängen mit einem höheren Bildungsniveau und der Erfahrung von adäquaten Schocks während des FU zusammen.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Al-Khatib SM, Stevenson WG, Ackerman MJ, Bryant WJ, Callans DJ, Curtis AB, Deal BJ, Dickfeld T, Field ME, Fonarow GC, Gillis AM, Granger CB, Hammill SC, Hlatky MA, Joglar JA, Kay GN, Matlock DD, Myerburg RJ, Page RL (2018) 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for Management of Patients with Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (writing committee to develop Guidelines for Management of Patients With Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death): developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. Heart Rhythm 15(10):e74–e189

Araya R, Lewis G, Rojas G, Fritsch R (2003) Education and income: which is more important for mental health? J Epidemiol Community Health 57(7):501–505

Behlouli H, Feldman DE, Ducharme A, Frenette M, Giannetti N, Grondin F, Michel C, Sheppard R, Pilote L (2009) Identifying relative cut-off scores with neural networks for interpretation of the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure questionnaire. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2009:6242–6246

Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D (2002) The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res 52:69–77

Brouwers C, van den Broek KC, Denollet J, Pedersen SS (2011) Gender disparities in psychological distress and quality of life among patients with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 34(7):798–803

Dunbar SB, Dougherty CM, Sears SF, Carroll DL, Goldstein NE, Mark DB, McDaniel G, Pressler SJ, Schron E, Wang P, Zeigler VL (2012) American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young. Educational and psychological interventions to improve outcomes for recipients of implantable cardioverter defibrillators and their families: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 126(17):2146–2172

Godemann F, Butter C, Lampe F, Linden M, Werner S, Behrens S (2004) Determinants of the quality of life (QoL) in patients with an implantable cardioverter/defibrillator (ICD). Qual Life Res 13:411–416

Goldstein NE, Lampert R, Bradley E, Lynn J, Krumholz HM (2004) Management of implantable cardioverter defibrillators in end-of-life care. Ann Intern Med 141(11):835–838

Goldstein NE, Mehta D, Siddiqui S, Teitelbaum E, Zeidman J, Singson M, Pe E, Bradley EH, Morrison RS (2008) “That’s like an act of suicide” patients’ attitudes toward deactivation of implantable defibrillators. J Gen Intern Med 23(Suppl 1):7–12

Gorkin L, Norvell NK, Rosen RC, Charles E, Schumaker SA, Mclntyre KM, Capone R, Kostis J, Niaura R, Woods P, for the SOLVD Investigators (1993) Assessment of quality of life as observed from the baseline data of the Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction (SOLVD) trial quality-of-life sub study. Am J Cardiol 71:1069–1073

Hamilton GA, Caroll DL (2004) The effects of quality of life in ICD recipients. J Clin Nurs 13:194–200

Kowey PR, Marinchak RA, Rials SJ (1992) Things that go bang in the night. N Engl J Med 327:1884

Kraaier K, Starrenburg AH, Verheggen RM, van der Palen J, Scholten MF (2013) Incidence and predictors of phantom shocks in implantable cardioverter defibrillator recipients. Neth Heart J 21(4):191–195

Kramer DB, Ottenberg AL, Gerhardson S, Mueller LA, Kaufman SR, Koenig BA, Mueller PS (2011) “Just Because We Can Doesn’t Mean We Should”: views of nurses on deactivation of pacemakers and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 32(3):243–252

Kuhl EA, Sears SF, Vazquez LD, Conti JB (2009) Patient-assisted computerized education for recipients of implantable cardioverter defibrillators: a randomized controlled trial of the PACER program. J Cardiovasc Nurs 24(3):225–231

Lampert R, Shusterman V, Burg M, McPherson C, Batsford W, Goldberg A, Soufer R (2009) Anger-induced T‑wave alternans predicts future ventricular arrhythmias in patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. J Am Coll Cardiol 53(9):774–778

Lemon J, Edelman S, Kirkness A (2004) Avoidance behaviors in patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillators. Heart Lung 33:176–182

Lewis G, Bebbington P, Brugha T, Farrell M, Gill B, Jenkins R, Meltzer H (2003) Socio-economic status, standard of living, and neurotic disorder. Int Rev Psychiatry 15(1–2:91–96

McManus S, Meltzer H, Brugha T, Bebbington P, Jenkins R (eds) (2007) Adult Psychiatric Morbidity in England 2007. Results of Household Survey. http://www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/PUB02931/adul-psyc-morb-res-hou-sur-eng-2007-rep.pdf. Accessed 09.2018

National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. (2011) Common Mental Health Disorders The NICE Guideline on Identification and Pathways to Care. National Clinical Guideline Number 123. http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/13476/54604/54604.pdf. Accessed 09.2018

Ohlow MA, Lauer B, Brunelli M, Daralammouri Y, Geller JC (2013) The use of a quadripolar left ventricular lead increases successful implantation rates in patients with phrenic nerve stimulation and/or high pacing thresholds undergoing cardiac resynchronization therapy with conventional bipolar leads. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J 13:58–65

Pedersen SS, Knudsen C, Dilling K, Sandgaard NCF, Johansen JB (2017) Living with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator: patients’ preferences and needs for information provision and care options. Europace 19(6):983–990

Prudente LA, Reigle J, Bourguignon C, Haines DE, DiMarco JP (2006) Psychological indices and phantom shocks in patients with ICD. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 15:185–190

Raphael CE, Koa-Wing M, Stain N, Wright I, Francis DP, Kanagaratnam P (2011) Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator recipient attitudes towards device deactivation: how much do patients want to know? Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 34(12):1628–1633

Rector TS, Tschumperlin LK, Kubo SH, Bank AJ, Francis GS, McDonald KM, Keeler CA, Silver MA (1995) Use of the Living with Heart Failure questionnaire to ascertain patients’ perspective on improvement in quality of life versus risk of drug-induced death. J Card Fail 1:201–206

Sears SF Jr, Todaro JF, Lewis TS, Sotile W, Conti JB (1999) Examining the psychosocial impact of implantable cardioverter defibrillators: a literature review. Clin Cardiol 22:481–489

Sheldon R, Connolly S, Krahn A, Roberts R, Gent M, Gardner M (2000) Identification of patients most likely to benefit from implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy: the Canadian Implantable Defibrillator Study. Circulation 101:1660–1664

Steele LS, Dewa CS, Lin E, Lee KL (2007) Education level, income level and mental health services use in Canada: associations and policy implications. Health Policy 3(1):96–106

Thomas SA, Friedmann E, Kelley FJ (2001) Living with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator: a review of the current literature related to psychosocial factors. AACN Clin Issues 12:156–163

Vazquez LD, Kuhl EA, Shea JB, Kirkness A, Lemon J, Whalley D, Conti JB, Sears SF (2008) Age-specific differences in women with implantable cardioverter defibrillators: an international multi-center study. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 31(12):1528–1534

Yen CF, Chen CC, Lee T, Tang TC, Ko CH, Yen JY (2005) Insight and correlates among outpatients with depressive disorders. Compr Psychiatry 46:384–389

Yu Y, Williams DR (1999) Socioeconomic status and mental health. In: Aneshensel CS, Phelan JC (eds) Handbook of the sociology of mental health. Kluiver Academic/Plenum Publishers, New York

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP (1983) The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 67:361–370

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the valuable work of the CIED nursing team: Christine Feser and Anne Hasch.

Funding

The authors declare that there are no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose. There was no relationship with the industry.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

S. Varghese, J. C. Geller and M.-A. Ohlow declare that they have no competing interests.

For this article no studies with human participants or animals were performed by any of the authors. All studies performed were in accordance with the ethical standards indicated in each case.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Varghese, S., Geller, J.C. & Ohlow, MA. Phantom shocks in implantable cardioverter-defibrillator recipients: impact of education level, anxiety, and depression. Herzschr Elektrophys 30, 306–312 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00399-019-00645-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00399-019-00645-y