Abstract

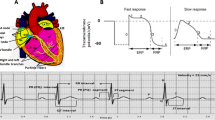

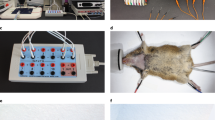

The most frequently used animal species in experimental cardiac electrophysiology are mice, rabbits, and dogs. Murine and human electrocardiograms (ECGs) show salient differences, including the occurrence of a pronounced J-wave and a less distinctive T-wave in the murine ECG. Mouse models can resemble human cardiac arrhythmias, although mice differ from human in cardiac electrophysiology. Thus, arrhythmia mechanisms in mice may differ from those in humans and should be transferred to the human situation with caution. Further relevant cardiovascular animal models are rabbits, dogs, and minipigs, as they show similarities of cardiac ion channel distribution with the human heart and are suitable to study ventricular repolarization or pro- and antiarrhythmic drug effects. ECG recordings in large animals like goats and horses are feasible. Both goats and horses are a suitable animal model to study atrial fibrillation (AF) mechanisms. Horses frequently show spontaneous AF due to their high vagal tone and large atria. The zebrafish has become an important animal model. Models in “exotic” animals such as kangaroos may be suitable for particular studies.

Zusammenfassung

Die wichtigsten elektrophysiologischen Tiermodelle sind das Maus-, Kaninchenund Hundeherz. Das Maus- und Mensch-EKG zeigen bedeutende Unterschiede wie eine ausgeprägte J Welle und eine allenfalls gering ausgebildete T Welle im Maus-EKG. Mäuse können trotz Unterschieden in der Elektrophysiologie zwischen Maus und Mensch humane Arrhythmien nachahmen. Daher können sich Arrhythmiemechanismen der Maus von denen im Menschen unterscheiden und sollten daher mit Behutsamkeit auf den Menschen übertragen werden. Kaninchen, Hunde und Schweine sind weitere relevante Tiermodelle und zeigen Ähnlichkeiten mit dem menschlichen Herzen in der Ionenkanalverteilung und sind daher ein geeignetes Model zur Untersuchung der ventrikulären Repolarisation und von pro- und antiarrhythmischen Medikamenteneffekten. EKGs können zudem auch in Ziegen und Pferden aufgezeichnet werden. Ziegen und Pferde sind geeignete Modelle zur Untersuchung von Vorhofflimmermechanismen. Bei Pferden tritt aufgrund des hohen Vagotonus und der großen Vorhofe häufig spontan Vorhofflimmern auf. Der Zebrafisch hat sich zu einem wichtigen Tiermodell entwickelt. „Exotische“ Tiere wie Kängurus sind für bestimmte Fragestellungen geeignete Modelle.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Kaese S, Verheule S (2012) Cardiac electrophysiology in mice: A matter of size. Front Physiol 3:345

Verheule S, Sato T, Everett TT 4th, Engle SK, Otten D, Rubart-von der Lohe M, Nakajima HO, Nakajima H, Field LJ, Olgin JE (2004) Increased vulnerability to atrial fibrillation in transgenic mice with selective atrial fibrosis caused by overexpression of TGF-beta1. Circ Res 94:1458–1465

Vaidya D, Morley GE, Samie FH, Jalife J (1999) Reentry and fibrillation in the mouse heart. A challenge to the critical mass hypothesis. Circ Res 85:174–181

Gralinski MR (2003) The dog’s role in the preclinical assessment of qt interval prolongation. Toxicol Pathol 31:11–16

Stubhan M, Markert M, Mayer K, Trautmann T, Klumpp A, Henke J, Guth B (2008) Evaluation of cardiovascular and ECG parameters in the normal, freely moving Göttingen Minipig. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods 57:202–211

Eckardt L, Breithardt G, Haverkamp W (2002) Electrophysiologic characterization of the antipsychotic drug sertindole in a rabbit heart model of torsade de pointes: low torsadogenic potential despite QT prolongation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 300:64–71

Ahmed JA, Sanyal S (2008) Electrocardiographic studies in Garol sheep and black Bengal goats. Res J Cardiol 1:1–8

Kant V, Srivastava AK, Verma PK, Raina R, Pankaj NK (2010) Alterations in electrocardiographic parameters after subacute exposure of fluoride and ameliorative action of aluminium sulphate in goats. Biol Trace Elem Res 134:188–194

Verheyen T, Decloedt A, De Clercq D, Deprez P, Sys SU, van Loon G (2010) Electrocardiography in horses—part 1: how to make a good recording. Vlaams Diergeneeskundig Tijdschrift 79:331–336

Verheyen T, Decloedt A, De Clercq D, Deprez P, Sys SU, van Loon G (2010) Electrocardiography in horses—part 2: how to read the equine ECG. Vlaams Diergeneeskundig Tijdschrift 79:337–344

Verheule S, Tuyls E, Gharaviri A, Hulsmans S, van Hunnik A, Kuiper M, Serroyen J, Zeemering S, Kuijpers NH, Schotten U (2013) Loss of continuity in the thin epicardial layer because of endomysial fibrosis increases the complexity of atrial fibrillatory conduction. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 6:202–211

Milan DJ, Jones IL, Ellinor PT, MacRae CA (2006) In vivo recording of adult zebrafish electrocardiogram and assessment of drug-induced QT prolongation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291:H269–273

Sugishita Y, Iida K, O’Rourke MF, Kelly R, Avolio A, Butcher D, Reddacliff G (1990) Echocardiographic and electrocardiographic study of the normal kangaroo heart. Aust N Z J Med 20:160–165

Meijler FL, Wittkampf FH, Brennen KR, Baker V, Wassenaar C, Bakken EE (1992) Electrocardiogram of the humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae), with specific reference to atrioventricular transmission and ventricular excitation. J Am Coll Cardiol 20:475–479

Gehrmann J, Berul CI (2000) Cardiac electrophysiology in genetically engineered mice. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 11:354–368

Gehrmann J, Hammer PE, Maguire CT, Wakimoto H, Triedman JK, Berul CI (2000) Phenotypic screening for heart rate variability in the mouse. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 279:H733–740

Kass DA, Hare JM, Georgakopoulos D (1998) Murine cardiac function: a cautionary tail. Circ Res 82:519–522

Sabir IN, Killeen MJ, Grace AA, Huang CL (2008) Ventricular arrhythmogenesis: insights from murine models. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 98:208–218

Liu G, Iden JB, Kovithavongs K, Gulamhusein R, Duff HJ, Kavanagh KM (2004) In vivo temporal and spatial distribution of depolarization and repolarization and the illusive murine T wave. J Physiol 555:267–279

Verheule S, van Batenburg CA, Coenjaerts FE, Kirchhoff S, Willecke K, Jongsma HJ (1999) Cardiac conduction abnormalities in mice lacking the gap junction protein connexin40. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 10:1380–1389

Mitchell GF, Jeron A, Koren G (1998) Measurement of heart rate and Q-T interval in the conscious mouse. Am J Physiol 274:H747–751

Gintant GA (1995) Regional differences in IK density in canine left ventricle: role of IK,s in electrical heterogeneity. Am J Physiol 268:H604–613

Milberg P, Eckardt L, Bruns HJ, Biertz J, Ramtin S, Reinsch N, Fleischer D, Kirchhof P, Fabritz L, Breithardt G, Haverkamp W (2002) Divergent proarrhythmic potential of macrolide antibiotics despite similar QT prolongation: fast phase 3 repolarization prevents early afterdepolarizations and torsade de pointes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 303:218–225

Frommeyer G, Milberg P, Witte P, Stypmann J, Koopmann M, Lucke M, Osada N, Breithardt G, Fehr M, Eckardt L (2011) A new mechanism preventing proarrhythmia in chronic heart failure: rapid phase-III repolarization explains the low proarrhythmic potential of amiodarone in contrast to sotalol in a model of pacing-induced heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 13:1060–1069

Frommeyer G, Rajamani S, Grundmann F, Stypmann J, Osada N, Breithardt G, Belardinelli L, Eckardt L, Milberg P (2012) New insights into the beneficial electrophysiologic profile of ranolazine in heart failure: prevention of ventricular fibrillation with increased postrepolarization refractoriness and without drug-induced proarrhythmia. J Card Fail 18:939–949

Eckardt L, Haverkamp W, Mertens H, Johna R, Clague JR, Borggrefe M, Breithardt G (1998) Drug-related torsades de pointes in the isolated rabbit heart: comparison of clofilium, d,l-sotalol, and erythromycin. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 32:425–434

Frommeyer G, Schmidt M, Clauss C, Kaese S, Stypmann J, Pott C, Eckardt L, Milberg P (2012) Further insights into the underlying electrophysiological mechanisms for reduction of atrial fibrillation by ranolazine in an experimental model of chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 14:1322–1331

Eckardt L, Meissner A, Kirchhof P, Weber T, Borggrefe M, Breithardt G, Van Aken H, Haverkamp W (2001) In vivo recording of monophasic action potentials in awake dogs—new applications for experimental electrophysiology. Basic Res Cardioll 96:169–174

Moise NS (1999) Inherited arrhythmias in the dog: potential experimental models of cardiac disease. Cardiovasc Res 44:37–46

Bode G, Clausing P, Gervais F, Loegsted J, Luft J, Nogues V, Sims J (2010) The utility of the minipig as an animal model in regulatory toxicology. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods 62:196–220

Schrickel JW, Bielik H, Yang A, Schimpf R, Shlevkov N, Burkhardt D, Meyer R, Grohe C, Fink K, Tiemann K, Luderitz B, Lewalter T (2002) Induction of atrial fibrillation in mice by rapid transesophageal atrial pacing. Basic Res Cardiol 97:452–460

Shan Z, Van Der Voort PH, Blaauw Y, Duytschaever M, Allessie MA (2004) Fractionation of electrograms and linking of activation during pharmacologic cardioversion of persistent atrial fibrillation in the goat. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 15:572–580

Milberg P, Frommeyer G, Kleideiter A, Fischer A, Osada N, Breithardt G, Fehr M, Eckardt L (2011) Antiarrhythmic effects of free polyunsaturated fatty acids in an experimental model of LQT2 and LQT3 due to suppression of early afterdepolarizations and reduction of spatial and temporal dispersion of repolarization. Heart Rhythm 8:1492–1500

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that there are no actual or potential conflicts of interest in relation to this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kaese, S., Frommeyer, G., Verheule, S. et al. The ECG in cardiovascular-relevant animal models of electrophysiology. Herzschr Elektrophys 24, 84–91 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00399-013-0260-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00399-013-0260-z