Abstract

Purpose

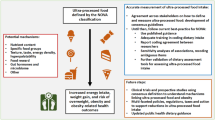

This study aims to describe micronutrient intake according to food processing degree and to investigate the association between the dietary share of ultra-processed foods and micronutrient inadequacies in a representative sample of Portuguese adult and elderly individuals.

Methods

Cross-sectional data from the National Food, Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey (2015/2016) were used. Food consumption data were collected through two 24-h food recalls, and food items were classified according to the NOVA system. Linear regression models were used to assess the association between the micronutrient density and the quintiles of ultra-processed food consumption—crude and adjusted. Negative Binomial regressions were performed to measure the prevalence ratio of micronutrient inadequacy according to ultra-processed food quintiles.

Results

For adults, all evaluated vitamins had significantly lower content in the fraction of ultra-processed foods compared to unprocessed or minimally processed foods, except vitamin B2. For the elderly, out of ten evaluated vitamins, seven presented significantly less content in ultra-processed foods compared to non-processed ones. The higher energy contribution of ultra-processed foods in adults was associated with a lower density of vitamins and minerals. This association was not observed in the elderly. For adults, compared with the first quintile of ultra-processed food consumption, the fifth quintile was positively associated with inadequate intakes of vitamin B6 (PR 1.51), vitamin C (PR 1.32), folate (PR 1.14), magnesium (PR 1.21), zinc (PR 1.33), and potassium (PR 1.19).

Conclusion

Our results corroborate the importance of public health actions that promote a reduction in the consumption of ultra-processed foods.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

WHO (World Health Organization) (2021) Fact sheets: malnutrition https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malnutrition (accessed April 2022)

Zhang P-Y, Xu X, Li X-C (2014) Cardiovascular diseases: oxidative damage and antioxidant protection. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 18:3091–3096

Draganidis D, Jamurtas AZ, Stampoulis T et al (2018) Disparate habitual physical activity and dietary intake profiles of elderly men with low and elevated systemic inflammation. Nutrients 10:e566

Louzada MLC, Martins APB, Canella DS et al (2015) Impact of ultra-processed foods on micronutrient content in the Brazilian diet. Rev Saúde Pública 49:45

Steele EM, Popkin BM, Swinburn B et al (2017) The share of ultra-processed foods and the overall nutritional quality of diets in the US: evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional study. Popul Health Metr 15:6

Moubarac JC, Batala M, Louzada ML et al (2017) Consumption of ultra-processed foods predicts diet quality in Canada. Appetite 108:512–520

Monteiro CA, Cannon G, Levy RB et al (2019) Ultra-processed foods: what they are and how to identify them. Public Health Nutr 22:936–941

Monteiro CA, Levy RB, Claro RM et al (2010) Increasing consumption of ultra-processed foods and likely impact on human health: evidence from Brazil. Pub Health Nutr 14:5–13

Baker P, Machado P, Santos T et al (2020) Ultra-processed foods and the nutrition transition: Global, regional and national trends, food systems transformations and political economy drivers. Obes Rev 21:e13126

Askari M, Heshmati J, Shahinfar H et al (2020) Ultra-processed food and the risk of overweight and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Int J Obes 44:2080–2091

Cordova R, Kliemann N, Huybrechts I et al (2021) Consumption of ultra-processed foods associated with weight gain and obesity in adults: A multi-national cohort study. Clin Nutr ESPEN 40:5079–5088

Rauber F, Chang K, Vamos EP et al (2021) Ultra-processed food consumption and risk of obesity: a prospective cohort study of UK Biobank. Eur J Nutr 60:2169–2180

Chen X, Zhang Z, Yang H et al (2020) Consumption of ultra-processed foods and health outcomes: a systematic review of epidemiological studies. Nutr J 19:86

Lane MM, Davis JÁ, Beattie S et al (2021) Ultraprocessed food and chronic noncommunicable diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 43 observational studies. Obes Rev 22:e13146

Miranda RC, Rauber F, Levy RB (2021) Impact of ultra-processed food consumption on metabolic health. Curr Opin Lipidol 32:24–37

Pagliai G, Dinu M, Madarena MP et al (2021) Consumption of ultra-processed foods and health status: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Nutr 125:3088

Steele EM, Baraldi LG, Louzada MLC et al (2016) Ultra-processed foods and added sugars in the US diet: evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 6:e009892

Cornwell B, Villamor E, Mora-Plazas M et al (2018) Processed and ultra-processed foods are associated with lower-quality nutrient profiles in children from Colombia. Public Health Nutr 21:142–147

Louzada MLC, Ricardo CZ, Steele EM et al (2018) The share of ultra-processed foods determines the overall nutritional quality of diets in Brazil. Public Health Nutr 21:94–102

Rauber F, Louzada MLC, Steele EM et al (2018) Ultra-processed food consumption and chronic non-communicable diseases-related dietary nutrient profile in the UK (2008–2014). Nutrients 10:587

Koiwai K, Takemi Y, Hayashi F et al (2019) Consumption of ultra-processed foods decreases the quality of the overall diet of middle-aged Japanese adults. Public Health Nutr 22:2999–3008

Marrón-Ponce JA, Flores M, Cediel G et al (2019) Associations between consumption of ultra-processed foods and intake of nutrients related to chronic non-communicable diseases in Mexico. J Acad Nutr Diet 119:1852–1865

Vandevijvere S, Ridder K, Fiolet T et al (2019) Consumption of ultra-processed food products and diet quality among children, adolescents and adults in Belgium. Eur J Nutr 58:3267–3278

Machado PP, Steele EM, Levy RB et al (2019) Ultra-processed foods and recommended intake levels of nutrientes linked to non-communicable diseases in Australia: evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 9:e029544

Andrade GC, Julia C, Deschamps V et al (2021) Consumption of ultra-processed food and its association with sociodemographic characteristics and diet quality in a representative Sample of French Adults. Nutrients 13:682

Chen YC, Huang YC, Lo YTC et al (2018) Secular trend towards ultra-processed food consumption and expenditure compromises dietary quality among Taiwanese adolescents. Food Nutr Res 62:1565

Miranda RC, Rauber F, Moraes MM et al (2020) Consumption of ultra-processed foods and non-communicable disease-related nutrient profile in Portuguese adults and elderly (2015–2016): the UPPER Project. Br J Nutr 125:1177–1187

Lopes C, Torres D, Oliveira A et al (2017) National food, nutrition and physical activity survey of the Portuguese general population. EFSA Support Publ 14:1341E

Lopes C, Torres D, Oliveira A et al (2018) National food, nutrition, and physical activity survey of the Portuguese general population (2015–2016): protocol for design and development. JMIR Res Protoc 7:e42

National Institute of Health Doutor Ricardo Jorge (2006) Food composition table. National Institute of Health Dr Ricardo Jorge, Lisbon

Roe MA, Bell S, Oseredczuk M et al (2013) Updated food composition database for nutrient intake. EFSA Support Publ 10:355E

Reinivuo H (2009) Harmonisation of recipe calculation procedures in European food composition databases. J Food Compost Anal 22:410–413

Monteiro CA, Cannon G, Moubarac JC et al (2018) The UN Decade of Nutrition, the NOVA food classification and the trouble with ultra-processing. Pub Health Nutr 21:5–17

Magalhães V, Severo M, Correia D et al (2021) Associated factors to the consumption of ultra-processed foods and its relation with dietary sources in Portugal. J Nutr Sci 10:e89

Harttig U, Haubrock J, Knüppel S et al (2011) The MSM program: web-based statistics package for estimating usual dietary intake using the Multiple Source Method. Eur J Clin Nutr 65:S87–S91

European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) (2017) Dietary reference values for nutrients summary report. Tech Rep. https://doi.org/10.2903/sp.efsa.2017.e15121

Dratva J, Gómez RF, Schindler C et al (2009) Is age at menopause increasing across Europe? Results on age at menopause and determinants from two population-based studies. Menopause 16:385–394

StataCorp, (2019) Stata statistical software: release 16. StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX

WHO (World Health Organization) (2003) Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases: report of a joint WHO/FAO expert consultation. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland

WHO (World Health Organization) (2013) WHO issues new guidance on dietary salt and potassium. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland

McLean RM, Farmer VL, Nettleton A et al (2018) Twenty-four–hour diet recall and Diet records compared with 24 hour urinary excretion to predict an individual’s sodium consumption: a systematic review. J Clin Hypertens 20:1360–1376

WHO (World Health Organization) (2012) WHO library cataloguing-in-publication data guideline: potassium intake for adults and children. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland

WHO (World Health Organization) (2012) WHO library cataloguing-in-publication data guideline: sodium intake for adults and children. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland

Moreira P, Sousa AS, Guerra RS et al (2018) Sodium and potassium urinary excretion and their ratio in the elderly: results from the Nutrition UP 65 study. Food Nutr Res 62:1288

Gonçalves C, Abreu S (2020) Sodium and potassium intake and cardiovascular disease in older people: a systematic review. Nutrients 12(11):3447

World Health Organization and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2006) Guidelines on food fortification with micronutrients.

Blanco-Rojo R, Vaquero P (2019) Iron bioavailability from food fortification to precision nutrition. A review. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol 51:126–138

Ohanenye IC, Emenike CU, Mensi A et al (2021) Food fortification technologies: Influence on iron, zinc and vitamin A bioavailability and potential implications on micronutrient deficiency in sub-Saharan Africa. Sci Afr 11:e00667

Zhou H, Zheng B, Zhang Z et al (2021) Fortification of plant-based milk with calcium may reduce Vitamin D bioaccessibility: an in vitro digestion study. J Agric Food Chem 69:4223–4233

Das JK, Salam RA, Mahmood SB et al (2019) Food fortification with multiple micronutrients: impact on health outcomes in general population (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011400.pub2

Popkin BM, Barquera S, Corvalan C et al (2021) Towards unified and impactful policies to reduce ultra-processed food consumption and promote healthier eating. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 9:462–470

Cherubini A, Vigna GB, Zuliani G et al (2005) Papel dos antioxidantes na aterosclerose: atualização epidemiológica e clínica. Curr Pharm Des 11:2017–2032

Kaliora AC, Dedoussis GV, Schmidt H (2006) Dietary antioxidants in preventing atherogenesis. Atherosclerosis 187:1–17

Acknowledgements

The acknowledgments of this study are directed to all individuals, healthcare workers, and researchers who participated in the IAN-AF.

Funding

This article is a result of the project ‘Consumption of ultra-processed foods, nutrient profile and obesity in Portugal (UPPER)’, supported by Competitiveness and Internationalization Operational Programme (POCI), under the PORTUGAL 2020 Partnership Agreement, through the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) and through national funds by the FCT– Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia. This work was also supported by the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) (grant numbers 2018/07391-9, 2019/05972-7, and 2020/15788-6).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Conceptualization: LA, RCDM, FR, RBL, and SR. Methodology: LA, RCDM, FR, MMDM, CA, CS, CL, SR, and RBL. Formal analysis and investigation: LA and RCDM. Writing—original draft preparation: LA. Writing—review and editing: LA, RCDM, FR, MMDM, CA, CS, CL, SR, and RBL. Funding acquisition: CL, SR, and RBL. Supervision: RBL and SR.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Antoniazzi, L., de Miranda, R.C., Rauber, F. et al. Ultra-processed food consumption deteriorates the profile of micronutrients consumed by Portuguese adults and elderly: the UPPER project. Eur J Nutr 62, 1131–1141 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-022-03057-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-022-03057-w