Abstract

Purpose

To determine whether (poly)phenols from gastrointestinal-digested green pepper possess genoprotective properties in human colon cells and whether the application of a culinary treatment (griddling) on the vegetable influences the potential genoprotective activity.

Methods

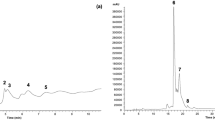

(Poly)phenols of raw and griddled green pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) submitted to in vitro-simulated gastrointestinal digestion were characterized by LC–MS/MS. Cytotoxicity (MTT, trypan blue and cell proliferation assays), DNA damage and DNA protection (standard alkaline and formamidopyrimidine DNA glycosylase (Fpg)-modified comet assay) of different concentrations of (poly)phenolic extracts were assessed in colon HT-29 cells.

Results

A total of 32 (poly)phenolic compounds were identified and quantified in digested raw and griddled green pepper. Twenty of them were flavonoids and 12 were phenolic acids. Griddled pepper doubled the (poly)phenol concentration compared to raw; luteolin 7-O-(2-apiosyl)-glucoside and quercitrin constituted the major (poly)phenols in both extracts. Raw and griddled pepper (poly)phenolic extracts impaired cell proliferation and induced low levels of Fpg-sensitive sites, in a dose-dependent manner, even at a non-cytotoxic concentration. None of the concentrations tested induced DNA strand breaks or alkaline labile sites. Nor did they show significant genoprotection against the DNA damage induced by H2O2 or KBrO3.

Conclusions

Green pepper (poly)phenols did not show genoprotection against oxidatively generated damage in HT-29 cells at simulated physiological concentrations, regardless of the application, or not, of a culinary treatment (griddling). Furthermore, high concentrations of (poly)phenolic extracts induced a slight pro-oxidant effect, even at a non-cytotoxic concentration.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Milic M, Frustaci A, Del Bufalo A et al (2015) DNA damage in non-communicable diseases: a clinical and epidemiological perspective. Mutat Res Mol Mech Mutagen 776:118–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2014.11.009

Cooke MS, Evans MD, Dizdaroglu M, Lunec J (2003) Oxidative DNA damage: mechanisms, mutation, and disease. FASEB J 17:1195–1214. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.02-0752rev

Del Rio D, Rodriguez-Mateos A, Spencer JPE et al (2013) Dietary (Poly)phenolics in human health: structures, bioavailability, and evidence of protective effects against chronic diseases. Antioxid Redox Signal 18:1818–1892. https://doi.org/10.1089/ars.2012.4581

Asnin L, Park SW (2015) Isolation and analysis of bioactive compounds in capsicum peppers. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 55:254–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2011.652316

Antonio AS, Wiedemann LSM, Veiga Junior VF (2018) The genus Capsicum: a phytochemical review of bioactive secondary metabolites. RSC Adv 8:25767–25784. https://doi.org/10.1039/C8RA02067A

Juániz I, Ludwig IA, Huarte E et al (2016) Influence of heat treatment on antioxidant capacity and (poly)phenolic compounds of selected vegetables. Food Chem 197:466–473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.10.139

Chen L, Kang Y-H (2013) Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities of red pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) stalk extracts: comparison of pericarp and placenta extracts. J Funct Foods 5:1724–1731. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2013.07.018

Park J-H, Jeon G-I, Kim J-M, Park E (2012) Antioxidant activity and antiproliferative action of methanol extracts of 4 different colored bell peppers (Capsicum annuum L.). Food Sci Biotechnol 21:543–550. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10068-012-0069-2

Materska M, Konopacka M, Rogoliński J, Ślosarek K (2015) Antioxidant activity and protective effects against oxidative damage of human cells induced by X-radiation of phenolic glycosides isolated from pepper fruits Capsicum annuum L. Food Chem 168:546–553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.07.023

Jeon G, Choi Y, Lee S-M et al (2012) Antioxidant and antiproliferative properties of hot pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) seeds. J Food Biochem 36:595–603. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-4514.2011.00571.x

Bacon K, Boyer R, Denbow C et al (2017) Antibacterial activity of jalapeño pepper (Capsicum annuum var. annuum) extract fractions against select foodborne pathogens. Food Sci Nutr 5:730–738. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.453

Kim J-S, Lee W-M, Rhee HC, Kim S (2016) Red paprika (Capsicum annuum L.) and its main carotenoids, capsanthin and β-carotene, prevent hydrogen peroxide-induced inhibition of gap-junction intercellular communication. Chem Biol Interact 254:146–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbi.2016.05.004

Fernández-Bedmar Z, Alonso-Moraga A (2016) In vivo and in vitro evaluation for nutraceutical purposes of capsaicin, capsanthin, lutein and four pepper varieties. Food Chem Toxicol 98:89–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2016.10.011

Juániz I, Ludwig IA, Bresciani L et al (2016) Catabolism of raw and cooked green pepper (Capsicum annuum) (poly)phenolic compounds after simulated gastrointestinal digestion and faecal fermentation. J Funct Foods 27:201–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2016.09.006

Hu M (2007) Commentary: Bioavailability of flavonoids and polyphenols: call to arms. Mol Pharm 4:803–806. https://doi.org/10.1021/mp7001363

Manach C, Scalbert A, Morand C et al (2004) Polyphenols: food sources and bioavailability. Am J Clin Nutr 79:727–747. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/79.5.727

Manach C, Williamson G, Morand C et al (2005) Bioavailability and bioefficacy of polyphenols in humans. I. Review of 97 bioavailability studies. Am J Clin Nutr 81:230S–242S. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/81.1.230S

Minekus M, Alminger M, Alvito P et al (2014) A standardised static in vitro digestion method suitable for food—an international consensus. Food Funct 5:1113–1124. https://doi.org/10.1039/C3FO60702J

Azqueta A, Collins AR (2013) The essential comet assay: a comprehensive guide to measuring DNA damage and repair. Arch Toxicol 87:949–968. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00204-013-1070-0

Dušinská M, Collins A (1996) Detection of oxidised purines and UV-induced photoproducts in DNA of single cells, by inclusion of lession-specific enzymes in the comet assay. ATLA 24:405–411

Azqueta A, Arbillaga L, Lopez de Cerain A, Collins A (2013) Enhancing the sensitivity of the comet assay as a genotoxicity test, by combining it with bacterial repair enzyme FPG. Mutagenesis 28:271–277. https://doi.org/10.1093/mutage/get002

Speit G, Schütz P, Bonzheim I et al (2004) Sensitivity of the FPG protein towards alkylation damage in the comet assay. Toxicol Lett 146:151–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxlet.2003.09.010

Smith CC, O’Donovan MR, Martin EA (2006) hOGG1 recognizes oxidative damage using the comet assay with greater specificity than FPG or ENDOIII. Mutagenesis 21:185–190. https://doi.org/10.1093/mutage/gel019

McDorman KS, Pachkowski BF, Nakamura J et al (2005) Oxidative DNA damage from potassium bromate exposure in Long-Evans rats is not enhanced by a mixture of drinking water disinfection by-products. Chem Biol Interact 152:107–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbi.2005.02.003

Morales-Soto A, Gómez-Caravaca AM, García-Salas P et al (2013) High-performance liquid chromatography coupled to diode array and electrospray time-of-flight mass spectrometry detectors for a comprehensive characterization of phenolic and other polar compounds in three pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) samples. Food Res Int 51:977–984. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2013.02.022

Chang EB, Leung PS (2014) Intestinal water and electrolyte transport. The gastrointestinal system. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 107–134

Mokhtar M, Soukup J, Donato P et al (2015) Determination of the polyphenolic content of a Capsicum annuum L. extract by liquid chromatography coupled to photodiode array and mass spectrometry detection and evaluation of its biological activity. J Sep Sci 38:171–178. https://doi.org/10.1002/jssc.201400993

Jeong WY, Jin JS, Cho YA et al (2011) Determination of polyphenols in three Capsicum annuum L. (bell pepper) varieties using high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry: Their contribution to overall antioxidant and anticancer activity. J Sep Sci 34:2967–2974. https://doi.org/10.1002/jssc.201100524

Azqueta A, Collins A (2016) Polyphenols and DNA damage: a mixed blessing. Nutrients 8:785. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu8120785

Babich H, Schuck AG, Weisburg JH, Zuckerbraun HL (2011) Research strategies in the study of the pro-oxidant nature of polyphenol nutraceuticals. J Toxicol 2011:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/467305

Brown EM, McDougall GJ, Stewart D et al (2012) Persistence of anticancer activity in berry extracts after simulated gastrointestinal digestion and colonic fermentation. PLoS ONE 7:e49740. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0049740

Gill CIR, Haldar S, Porter S et al (2004) The effect of cruciferous and leguminous sprouts on genotoxicity, in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 13:1199–1206

Ramos AA, Marques F, Fernandes-Ferreira M, Pereira-Wilson C (2013) Water extracts of tree Hypericum sps. protect DNA from oxidative and alkylating damage and enhance DNA repair in colon cells. Food Chem Toxicol 51:80–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2012.09.014

Sukprasansap M, Sridonpai P, Phiboonchaiyanan PP (2019) Eggplant fruits protect against DNA damage and mutations. Mutat Res Mol Mech Mutagen 813:39–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2018.12.004

Beserra AMSS, Vilegas W, Tangerina MMP et al (2018) Chemical characterisation and toxicity assessment in vitro and in vivo of the hydroethanolic extract of Terminalia argentea Mart. leaves. J Ethnopharmacol 227:56–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2018.08.025

Elbling L, Weiss R-M, Teufelhofer O et al (2005) Green tea extract and (–)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate, the major tea catechin, exert oxidant but lack antioxidant activities. FASEB J 19:807–809. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.04-2915fje

Pool-Zobel BL, Adlercreutz H, Glei M et al (2000) Isoflavonoids and lignans have different potentials to modulate oxidative genetic damage in human colon cells. Carcinogenesis 21:1247–1252. https://doi.org/10.1093/carcin/21.6.1247

Corona G, Coman MM, Guo Y et al (2017) Effect of simulated gastrointestinal digestion and fermentation on polyphenolic content and bioactivity of brown seaweed phlorotannin-rich extracts. Mol Nutr Food Res 61:1700223. https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.201700223

Aknowledgements

This research was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (AGL2014-52636-P, AGL2015-70640-R) and University of Navarra (PIUNA 2018-09). E. Huarte thanks the Association of Friends of the University of Navarra for the PhD grant received. A. Azqueta thanks the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (‘Ramón y Cajal’ programme, RYC-2013-14370) of the Spanish Government for personal support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Huarte, E., Cid, C., Azqueta, A. et al. DNA damage and DNA protection from digested raw and griddled green pepper (poly)phenols in human colorectal adenocarcinoma cells (HT-29). Eur J Nutr 60, 677–689 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-020-02269-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-020-02269-2