Abstract

Background

Gait and cognition are closely associated. Older adults with gait deficits have an increased risk of developing cognitive deficits and cognitive deficits are associated with worsened gait. Both gait and cognitive impairments are risk factors for falls in older adults.

Objectives

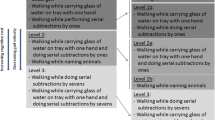

The aims of this article are (1) to highlight the association between gait and cognition, particularly executive function, (2) to present motor cognitive dual tasking test paradigms and (3) to provide an algorithm for standardized mobility tests that can quickly and easily be performed in a private practice or on a hospital ward.

Materials and methods

A Pubmed review of current literature on the topic as well as the personal experience and recommendations of the authors are presented. Assessments summarized: clock drawing test, stops walking when talking test, normal walking speed, timed up and go test, regular, as a dual task and imagined.

Results

It is recommended that at least two of the presented assessments should be performed at each clinical visit in all patients age 65 years or older. If one of the assessments presented provides abnormal results, patients should be referred to a gait specialist for an in-depth quantitative gait analysis.

Conclusion

Assessments of functional mobility, fall risk and cognition should be an integral part of every comprehensive geriatric assessment. Quantitative gait analysis allows not only the early detection of gait deficits and fall risk, but also of cognitive deficits. Early detection allows for timely implementation of targeted interventions to improve gait and/or cognition.

Zusammenfassung

Hintergrund

Gang und Kognition sind eng assoziiert. Ältere Erwachsene mit Gangdefiziten haben ein erhöhtes Risiko, kognitive Defizite zu entwickeln. Kognitive Defizite sind mit einer Gangverschlechterung assoziiert. Sowohl Gang- als auch kognitive Beeinträchtigungen sind Sturzrisikofaktoren bei älteren Menschen.

Ziele

1) Die Assoziation zwischen Gang und Kognition, insbesondere Exekutivfunktionen, zu beleuchten, 2) motorisch-kognitive Dual-task-Testparadigmen darzustellen und 3) einen Algorithmus für standardisierte Mobilitätsuntersuchungen zu präsentieren, die sich schnell und einfach in Praxis oder Klinik durchführen lassen.

Material und Methoden

Vorgestellt werden die Ergebnisse einer Sichtung der aktuellen Literatur in PubMed sowie persönliche Erfahrungen und Empfehlungen der Autoren. Zusammengefasste Assessment-Verfahren: Uhrentest, SWWT(„stops walking when talking“)-Test, normale Gehgeschwindigkeit, Timed-up-and-Go-Test (normal, als eine doppelte Aufgabe und imaginär).

Ergebnisse

Empfohlen wird, bei jedem klinischen Besuch mit allen Patienten, die 65 Jahre alt oder älter sind, mindestens 2 der erwähnten Untersuchungen durchzuführen. Falls sich bei mindestens einem Test Auffälligkeiten ergeben, sollten Patienten einem Spezialisten für eine gründliche quantitative Ganganalyse zugewiesen werden.

Diskussion

Untersuchungen zu funktioneller Mobilität, Sturzrisiko und Kognition sollten in jedes umfassende geriatrische Assessment integriert sein. Quantitative Ganganalysen erlauben nicht nur eine Früherkennung von Gangdefiziten und Sturzrisiko, sondern auch von kognitiven Defiziten. Eine Früherkennung ermöglicht den zeitgerechten Einsatz gezielter Interventionen, um Gang und/oder Kognition zu verbessern.

Similar content being viewed by others

Literature

Alexander BH, Rivara FP, Wolf ME (1992) The cost and frequency of hospitalization for fall-related injuries in older adults. Am J Public Health 82(7):1020–1023

Barry E et al (2014) Is the Timed Up and Go test a useful predictor of risk of falls in community dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr 14:14

Beauchet O et al (2010) Imagined Timed Up & Go test: a new tool to assess higher-level gait and balance disorders in older adults? J Neurol Sci 294(1–2):102–106

Beauchet O et al (2014) Motor imagery of gait: a new way to detect mild cognitive impairment? J Neuroeng Rehabil 11:66

Bridenbaugh SA, Kressig RW (2011) Laboratory review: the role of gait analysis in seniors’ mobility and fall prevention. Gerontology 57(3):256–264

Bridenbaugh SA, Kressig RW (2014) Quantitative gait disturbances in older adults with cognitive impairments. Curr Pharm Des 20(19):3165–3172

Bridenbaugh SA et al (2013) Association between dual task-related decrease in walking speed and real versus imagined Timed Up and Go test performance. Aging Clin Exp Res 25(3):283–289

Buracchio T et al (2010) The trajectory of gait speed preceding mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol 67(8):980–986

Ferri CP et al (2005) Global prevalence of dementia: a Delphi consensus study. Lancet 366(9503):2112–2117

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR (1975) “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12(3):189–198

Ganz DA et al (2007) Will my patient fall? JAMA 297(1):77–86

Hausdorff JM, Rios DA, Edelberg HK (2001) Gait variability and fall risk in community-living older adults: a 1-year prospective study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 82(8):1050–1056

Hornbrook MC et al (1994) Preventing falls among community-dwelling older persons: results from a randomized trial. Gerontologist 34(1):16–23

Lundin-Olsson L, Nyberg L, Gustafson Y (1997) “Stops walking when talking” as a predictor of falls in elderly people. Lancet 349(9052):617

Maki BE (1997) Gait changes in older adults: predictors of falls or indicators of fear. J Am Geriatr Soc 45(3):313–320

Monsch AU, Kressig RW (2010) Specific care program for the older adults: memory clinics. Eur Geriatr Med 1:128–131

Montero-Odasso M et al (2009) Can cognitive enhancers reduce the risk of falls in older people with mild cognitive impairment? A protocol for a randomised controlled double blind trial. BMC Neurol 9:42

Montero-Odasso M et al (2012) Gait and cognition: a complementary approach to understanding brain function and the risk of falling. J Am Geriatr Soc 60(11):2127–2136

Morris JC et al (1987) Senile dementia of the Alzheimer’s type: an important risk factor for serious falls. J Gerontol 42(4):412–417

Muhaidat J et al (2014) Validity of simple gait-related dual-task tests in predicting falls in community-dwelling older adults. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 95(1):58–64

Podsiadlo D, Richardson S (1991) The timed “Up & Go”: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 39(2):142–148

Prevention CfDCa (2009) Falls among older adults: fact sheets. http://www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/falls/adultfalls.html

Rubenstein LZ, Josephson KR (2002) The epidemiology of falls and syncope. Clin Geriatr Med 18(2):141–158

Shulman KI (2000) Clock-drawing: is it the ideal cognitive screening test? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 15(6):548–561

Sterling DA, O’Connor JA, Bonadies J (2001) Geriatric falls: injury severity is high and disproportionate to mechanism. J Trauma 50(1):116–119

Studenski S et al (2011) Gait speed and survival in older adults. JAMA 305(1):50–58

Theill N et al (2011) Simultaneously measuring gait and cognitive performance in cognitively healthy and cognitively impaired older adults: the Basel motor-cognition dual-task paradigm. J Am Geriatr Soc 59(6):1012–1018

Tinetti ME, Speechley M, Ginter SF (1988) Risk factors for falls among elderly persons living in the community. N Engl J Med 319(26):1701–1707

Verghese J et al (2007) Quantitative gait dysfunction and risk of cognitive decline and dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 78(9):929–935

Verghese J et al (2014) Motoric cognitive risk syndrome: multicountry prevalence and dementia risk. Neurology 83(8):718–726

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

S.A. Bridenbaugh and R.W. Kressig have no conflicts of interest to declare.

This article is a literature review and does not include studies on humans or animals.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bridenbaugh, S., Kressig, R. Motor cognitive dual tasking. Z Gerontol Geriat 48, 15–21 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00391-014-0845-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00391-014-0845-0