Abstract

The most pronounced mode of climate variability during the last glacial period are the so-called Dansgaard–Oeschger events. There is no consensus of the underlying dynamical mechanism of these abrupt climate changes and they are elusive in most simulations of state-of-the-art coupled climate models. There has been significant debate over whether the climate system is exhibiting self-sustained oscillations with vastly varying periods across these events, or rather noise-induced jumps in between two quasi-stable regimes. In previous studies, statistical model comparison has been employed to the NGRIP ice core record from Greenland in order to compare different classes of stochastic dynamical systems, representing different dynamical paradigms. Such model comparison studies typically rely on accurately reproducing the observed records. We aim to avoid this due to the large amount of stochasticity and uncertainty both on long and short time scales in the record. Instead, we focus on the most important qualitative features of the data, as captured by summary statistics. These are computed from the distributions of waiting times in between events and residence times in warm and cold regimes, as well as the stationary density and the autocorrelation function. We perform Bayesian inference and model comparison experiments based solely on these summary statistics via Approximate Bayesian Computation. This yields an alternative approach to existing studies that helps to reconcile and synthesize insights from Bayesian model comparison and qualitative statistical analysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The last glacial period, lasting from roughly 120 to 12 kyr before present (1 kyr = 1 thousand years), has seen around 30 very abrupt changes in climate conditions of the Northern Hemisphere, known as Dansgaard–Oeschger (DO) events (Dansgaard et al. 1993). These events are the most pronounced climate variability on the sub-orbital timescales, i.e., below \(\approx\) 20 kyr. In Greenland, they are marked by rapid warmings from cold conditions (stadials) to approximately 10 K warmer conditions (interstadials) within a few decades (see Rasmussen et al. (2014) for a definition of stadials and interstadials from Greenland ice cores). This is usually followed by a more gradual cooling, which precedes a quick jump back to stadial conditions. The spacing and duration of individual events is highly variable and largely uncorrelated in time over the course of the last glacial period. Some interstadials show gradual cooling for thousands of years, while others jump back to stadial conditions within 100–200 years. DO events are the primary evidence that large-scale climate change can happen on centennial and even decadal timescales. It is thus imperative to understand the underlying mechanisms of past abrupt climate changes, in order to obtain a more complete understanding of the climate system and thereby improve predictions of future anthropogenic climate change.

While significant climate change concurrent with DO events is well documented in various climate proxies from marine and terrestrial archives all over the Northern Hemisphere, it is most clearly observed in proxy records from Greenland ice cores. An important proxy is \(\delta ^{18}\)O, which measures the ratio of the heavy oxygen isotope \(^{18}\)O to the light isotope \(^{16}\)O in the ice. This ratio is widely accepted as a proxy for temperature at the accumulation site. We consider the \(\delta ^{18}\)O record of the NGRIP ice core, which has been measured in 5 cm samples along the core. This results in an unevenly spaced time series with a resolution of 3 years at the end to 10 or more years at the beginning of the last glacial period. It is a matter of debate whether the highest frequencies in ice core records correspond to a true large-scale climate signal. Studies of ice coring sites with low accumulation rates have shown that the highest frequencies in the record can be dominated by post-depositional disturbances to the snow (Münch et al. 2016). To facilitate analysis and to filter out some of these high frequencies, we will use an evenly spaced time series of 20 year binned and averaged \(\delta ^{18}\)O measurements. Still, it is unclear to what degree adjacent samples of this time series represent true large-scale climate variability. In our attempt to analyze and model the data, we instead concentrate on characteristic statistical features, which do not concern the highest frequencies in the record.

Even after decades of research following their discovery, there is no consensus on the triggers of DO events, or on whether they are a manifestation of internal climate variability. In simulations of globally coupled climate models, DO-type events are largely elusive, although some recent studies report occurrences thereof, albeit through different mechanisms at play. Furthermore, only very few instances of truly unforced abrupt, large-scale climate changes have been seen in realistic climate models (Drijfhout et al. 2013; Kleppin et al. 2015). Development in this area is hampered by very high computational costs of investigating millennial-scale phenomena with high-resolution climate models. Similarly, the paleoclimate data community has not settled on a comprehensive explanation by examining evidence from different proxy variables at different locations. With this work, we want to advance the understanding of mechanisms that could be a likely cause of DO events. We attempt to investigate whether it is possible to establish evidence in favor of one physical mechanism above others from the NGRIP \(\delta ^{18}\)O time series alone. To this end, we compare a suite of simple, stochastic dynamical systems models to each other via Bayesian model comparison. The models represent different dynamical paradigms and arise as conceptual climate models with different underlying physical hypotheses.

The NGRIP data set is characterized by high amounts of irregularity that is displayed both on very short time scales (possibly non-climatic noise) and longer time scales, as manifested in the high temporal irregularity of the abrupt events. We thus choose to view the time series at hand as one realization of a stochastic process, produced by the complex and chaotic dynamics of the climate system. As a consequence, we want to avoid fitting the models point-wise to the data, but rather demand the models to display similar qualitative, statistical features, such that the observations could be a likely or possible realization of the model. In order to do that in a quantitative way, we construct a set of summary statistics replacing the actual time series. Performing Bayesian parameter inference and model comparison implies the evaluation of a likelihood function of a model given a set of parameters and data. Since the likelihood function of our models is completely intractable, especially in the presence of summary statistics, we have to adopt a likelihood-free method. One method permitting this is called Approximate Bayesian Computation (ABC, first developed in Pritchard et al. (1999), see Marin et al. (2012) for a review). This technique allows us to approximate Bayes factors and posterior parameter distribution. Compared to simply estimating maximum likelihood parameters, this is advantageous because we can assess the models’ sensitivity in parameter space and see how well constrained individual model parameters are by the data.

The paper is organized in the following way. In Sect. 2 we will present the models examined in this study, along with some physical considerations motivating the study of these. In Sect. 3, our method is presented, i.e., the construction of summary statistics as well as the parameter inference and model comparison approach. Our results are given in Sect. 4, where we first demonstrate the method with a study on synthetic data in Sect. 4.1 and then present the study on the NGRIP data set in Sect. 4.2. We discuss our results and conclude in Sect. 5.

2 Models

The models considered in this study can be viewed as a collection of minimal models, which permit the different dynamical regimes that have been reported in studies showing DO-type variability in detailed climate models, i.e., noise-induced transitions, excitability and self-sustained relaxation oscillations. This allows us to restrict our analysis to stochastic differential equations of two variables, where the variable x will be identified with the climate proxy. Several well-studied stochastic dynamical systems models are of the following form:

The individual models investigated by us differ in the choice of f(x, y) and specific parameters. They are commonly known as double well potential (DW), Van der Pol oscillator (VDP, VDP\(_Y\)) and FitzHugh-Nagumo model (FHN, FHN\(_Y\)), and are defined as follows:

The DW model corresponds to stochastic, overdamped motion of a particle in a double well potential. It has been proposed previously as model for glacial climate variability (Ditlevsen 1999; Timmermann and Lohmann 2000), and displays jumps in between cold and warm states at random times similar to a telegraph process. It can be derived from Stommel’s classic model of a bi-stable Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), which has been one of the most prevalent mechanisms invoked to explain DO events (Stommel 1961). Including stochastic wind stress forcing in the Stommel model in the limit of very fast ocean temperature equilibration yields stochastic motion in a double well potential, where the single remaining variable describes the salinity difference of polar and equatorial Atlantic, which is proportional to the AMOC circulation strength (Stommel and Young 1993; Cessi 1994).

Phase portrait and nullclines of the VDP and FHN models with \(a_1=4\) and \(a_3=1\). The nullclines of the x variables are given by \(y = (a_3x^3 - a_1x)/b\) and are drawn in black for \(b=1.5\) in all panels. The solid part of that curve is the slow manifold. Stable (unstable) spirals are marked by solid (open) circles, and saddle points by open diamonds. a Two y-nullclines of the VDP model given by \(x=c\), indicating a transition from oscillatory (\(c=-0.5\), limit cycle drawn in orange) to excitable dynamics (\(c=-1.3\)). bx-nullclines of the VDP model for two different values of b indicating a stretching of the slow manifold and thus a lengthening of the period in the oscillatory regime. c Three y-nullclines of the FHN model given by \(y=(x-c)/tan (x)\), indicating a transition from oscillatory (\(\beta =-0.1\)) to excitable (\(\beta =-0.4\)) and bi-stable (\(\beta =-1\)) dynamics

Similarly, relaxation oscillators, such as the VDP or FHN models, have been proposed for modeling Greenland ice cores (Kwasniok 2013; Roberts and Saha 2016; Mitsui and Crucifix 2017). At first glance, they seem good candidates for generating DO events, since during a relaxation oscillation cycle one can get a characteristic fast rise and slow decay of the fast variable in a certain parameter regime (\(c \ne 0\)). We illustrate the most important dynamical regimes in Fig. 1. In the VDP model, the oscillatory regime is given if |c| is small compared to the ratio \(a_1/a_3\). On the other hand, as depicted in Fig. 1a, if |c| is beyond a certain critical value, the deterministic system has one stable fixed point. Noise perturbations can kick the system out of this fixed point and excite a larger excursion in phase space until the fixed point is reached again. This is often referred to as the excitable regime. If we decrease b in the oscillatory regime, the period of oscillation grows, as the trajectory spends more time close to the stable parts of the nullcline of the x variable, which is also referred to as the slow manifold and is indicated in Fig. 1b. In the limit of \(b=0\) in Eq. 1, the variables decouple and we are left with a double well potential model for the variable x. Thus, both VDP and FHN models include a symmetric (\(a_0 = 0\)) DW model as a special case. The general form in Eq. 1 permits transitions between the very different models proposed in the literature by continuous changes of parameter values. Similarly, the oscillator models we consider are nested, as explained in the following.

The VDP model is a special case of the FHN model, obtained by setting \(\beta = 0\). Initially developed as simplified model for spiking neurons, the FHN model can display even richer dynamical behaviors including relaxation oscillations, excitability and bi-stability. The latter regime occurs for negative \(\beta\), where below a certain critical value two stable fixed points emerge. As b decreases, this critical value gets closer to zero. Including additive noise in this regime induces stochastic jumps in between the two states. We indicated a transition from oscillatory to excitable and bi-stable dynamics by changing \(\beta\) and otherwise fixed parameters in Fig. 1c. For more details on the dynamics of the VDP and FHN models, and the rich bifurcation structure that appears especially close to the boundaries of the dynamical regimes, we refer the reader to Rocsoreanu et al. (2000). Relaxation oscillator models, similar to the ones regarded in this study, can also be derived from Stommel’s model, e.g., by including an additional feedback from the ocean state to the atmosphere (Roberts and Saha 2016). In this case, the first variable describes the salinity difference of polar and equatorial Atlantic, and the second describes the ratio of the effect of atmospheric salinity forcing on ocean density to that of atmospheric temperature forcing. We include noise forcing in the oscillator models, which is crucial in order to obtain the highly irregular oscillatory behavior that is seen in the data.

We simulate all models with a Euler-Maruyama method, a time step of \(\varDelta t = 0.0005\) and time scaled to units of 1 kyr. The actual model output we consider is given as a binned average of 20 years, i.e. 40 time steps, mirroring the pre-processing of the NGRIP data at hand.

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Data

Our model comparison study starts by preprocessing the NGRIP data set, as explained in the following. We use the 20 year averaged \(\delta ^{18}\)O data on the GICC05modelext time scale, as published by Rasmussen et al. (2014). We remove a 25 kyr running mean, corresponding to a high pass eliminating variations due to orbital forcing on time scales longer than 20 kyr, which are not investigated in this study. Like this, we are able to assess the statistical properties of the sub-orbital timescale dynamics in the signal using summary statistics. Finally, we cut the time series starting at 110 kyr, i.e. during GS-25 (GS = Greenland interstadial), and ending at 23 kyr b2k (before AD 2000), i.e. just after GI-2.2 (GI = Greenland interstadial). We do this in order to exclude the high early glacial \(\delta ^{18}\)O values before GS-25 and the rising \(\delta ^{18}\)O values in GS-2.1 with very high noise level in order to be able to objectively define warming events, as described below. The resulting time series is shown in Fig. 2.

3.2 Summary statistics

As next prerequisite to perform parameter inference and model comparison one needs to specify a measure to quantify the goodness-of-fit of model output with respect to data. We do not compare model output time series and data pointwise, e.g., using a root mean squared error. Due to the high stochasticity displayed in the data, it is irrelevant and possibly overfitting to find a model which would be able to produce a time series which is pointwise close to the data. Practically, one can use one-step prediction errors, assuming these are uncorrelated Gaussian. This has been done with the NGRIP record using Kalman filtering (Kwasniok and Lohmann 2009; Kwasniok 2013; Mitsui and Crucifix 2017). However, due to the high noise level and uncertainty in the interpretation of high-frequencies in the ice core data, our strategy is to replace the time series with a set of summary statistics and assess goodness-of-fit by comparing summary statistics of model and data time series. The summary statistics are described in the following.

We choose summary statistics which contain as much information as possible about the qualitative aspects of the NGRIP data that we want our models to reproduce. First of all, the models should show DO-type events, i.e. switching in between higher and lower proxy values. To define events, we introduce one lower and one upper threshold at \(x=-1\) and \(x=1.5\), respectively. An up-switching event is defined by the first up-crossing of the upper threshold after up-crossing the lower threshold (Ditlevsen et al. 2007). In the same way, the first down-crossing of the lower threshold after down-crossing the upper threshold defines a down-switching event. The result of this procedure applied to the detrended NGRIP data can be seen in Fig. 2. Periods in between up- and down-switching events (and vice versa) are denoted as interstadials (stadials). The thresholds are defined such that when applied to the detrended NGRIP data, the original classification of DO events and Greenland stadials/interstadials is reasonably well preserved (Rasmussen et al. 2014). Our classification differs such that GI-5.1 is not detected and GI-16.2 and 16.1 are detected as one single interstadial. Additionally, three very short spikes, which are not classified DO events, are identified as warming events (in GS-8, GS-9 and GS 19.1). We furthermore detect some of the most pronounced climate changes typically classified as DO sub-events, yielding 35 warming events in total.

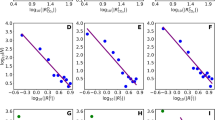

Statistical properties investigated in this study. a–c Complement of empirical cumulative distribution function \(1-\text {ECDF} = P(X>x)\) of stadial durations, interstadial durations and waiting times, respectively. The NGRIP data statistics are shown in red, the asymptotic statistics for a DW model with \(a_0=0.16\), \(a_1=2.86\), \(a_3=0.93\) and \(\sigma =4.17\) is shown in black, corresponding 95% simultaneous confidence bands are shown with blue shading and an example realization is shown in gray. The maximal vertical distances of data and model realization are illustrated with dashed lines and correspond to our summary statistics \(s_1\), \(s_2\) and \(s_3\). d Probability density function (PDF) of the time series, used to compute \(s_4\). e Autocorrelation function up to a lag of 2250 years, which underlies \(s_5\)

With events defined as above we construct three summary statistics in the following way: Since one notable characteristic of the data is a broad distribution of durations in between events, we compare models and data using empirical cumulative distribution functions (ECDFs) of these durations. Specifically, given a time series, ECDFs are constructed for durations of stadials, interstadials, and for the waiting times in between adjacent warming events. Two time series are then compared by computing the Kolmogorov–Smirnov distance of the respective ECDFs, which yields a scalar measure of goodness-of-fit for each of the statistical properties. These are denoted as \(s_1\), \(s_2\) and \(s_3\), for stadial durations, interstadial durations and waiting times in between warming events, respectively. We visualize this construction in Fig. 3a–c.

We introduce a fourth summary statistic in order to capture the bi-modal structure of the NGRIP time series, which is best observed from the stationary density shown in Fig. 3d. We compute the ECDF of the whole time series and make a pairwise comparison by computing the Kolmogorov–Smirnov distance, which we denote as \(s_4\).

Finally, to capture the persistence properties of the detrended climate record, we base another summary statistic on the autocorrelation function up to a lag of 2250 years, as shown in Fig. 3e for both NGRIP data and a DW model. Two time series are compared by computing the root mean squared deviation (RMSD) of their autocorrelation functions, which will be denoted as \(s_5\). This yields a total of 5 scalar quantities to assess the fit of model output to data, which we summarize in a vector \(\underline{s} = (s_1,s_2,s_3,s_4,s_5)^T\). For a good fit, we require all individual components to be sufficiently small, as will be discussed in more detail below.

An important qualitative feature of the NGRIP record so far missing from this description with summary statistics is the characteristic saw-tooth shape of the DO events. This behavior can also be captured with summary statistics, but with the models considered here it turns out to be hardly compatible with the other summary statistics introduced above. We discuss this statistical feature separately in Sect. 4.2.3. Statistical indicators, which go beyond the characteristic features of the record that we aim to describe, are not considered. As explained in the introduction, due to lack of confidence in the climatic signal of the highest frequencies in the record, we discard indicators concerning the ’fine-structure’ of the record, such as the distribution of increments. Furthermore, our analysis is restricted to stationary models, and thus statistical indicators measuring non-stationarity cannot be included. Higher-order statistics, such as third-order correlations or cumulants, could be considered in future studies. While it is possible that higher-order statistics carry important features of the data, this is still debated (Rypdal and Rypdal 2016) and beyond the scope of our study.

3.3 Inference and model comparison

The measures for goodness-of-fit as defined above enable us to perform parameter inference and model comparison in an approximate Bayesian approach. Specifically, we aim to approximate two entities. First, for a given model \(\mathcal {M}_i\), we want to sample from the posterior distribution of model parameters \(\theta _i\) given data D

where \(p(\theta _i|\mathcal {M}_i)\) is a prior distribution of the parameters. Second, we wish to compute the relative probabilities of different models given the data \(p(\mathcal {M}_i |D)\), which is evaluated using Bayes’ theorem:

Here, \(p(\mathcal {M}_i)\) is the prior probability of model \(\mathcal {M}_i\). Thus, the relative posterior probability of two models is

where \(\mathcal {B}_{1,2}\) is called the Bayes’ factor and \(p(D|\mathcal {M}_i)\) is referred to as the model evidence. The latter is an integral over parameter space of the product of likelihood and prior:

As a consequence of this integration, models with high-dimensional parameter spaces are disfavored over simpler, more parsimonious models that fit the data equally well. In models with many parameters, a large part of the parameter space results in a poor fit to the data, which yields a low model evidence, since Eq. 6 can be viewed as an average over the parameter space weighted by the prior. The highest model evidence is obtained for models where most of the parameter space yields a good fit to the data. We explore the magnitude of this penalty on models with superfluous parameters in our model comparison implementation in Sect. 4.1.2.

The computation of both the posterior parameter distribution \(p(\theta _i |D, \mathcal {M}_i)\) and the model evidence \(p(D| \mathcal {M}_i)\) require the likelihood \(p(D|\theta _i, \mathcal {M}_i)\), which is intractable for our models and summary statistics. We thus adopt a likelihood-free method called Approximate Bayesian computation (ABC). In this method we assume the data D to be in a (high-dimensional) data space \(\mathcal {D}\) with a metric \(\rho (\cdot ,\cdot )\). We can thus write

where \(x \in \mathcal {D}\) and \(\delta (x)\) is the Dirac delta function on \(\mathcal {D}\) defined by \(\int f(x) \delta (x) dx = f(0)\). \(\pi _{\epsilon , D}(x)\) is a normalized kernel, defined as \(\pi _{\epsilon , D}(x) = I_{B_{\epsilon }(D)} (x) \, V_{\epsilon }^{-1}\), where \(I_{B_{\epsilon }(D)}\) is the indicator function for a ball of radius \(\epsilon\) centered at D and \(V_{\epsilon }\) is the volume of the ball. For small \(\epsilon\), \(\pi _{\epsilon , D}(x)\) is thus strongly peaked where x is similar to the data D according to the metric \(\rho\). These definitions yield the following expression for the marginal likelihood

and the Bayes factor of two models is given by

In ABC, this expression is approximated by choosing a finite tolerance \(\epsilon\) and by estimating the integrals via Monte Carlo integration in the following way. For a given model one repeatedly samples a parameter \(\theta\) from the prior \(p(\cdot | \mathcal {M}_i)\), simulates a model output \(x_j\) and accepts the parameter value \(\theta\) as a sample from the posterior distribution if \(I_{B_{\epsilon }(D)}(x_j) = 1\), i.e. \(\rho (x_j,D) \le \epsilon\). This yields a sampling estimate of the ABC approximation to the desired posterior parameter distribution. By performing the procedure for two competing models, we obtain a Monte Carlo estimate of the ABC approximation to the Bayes factor

where \(x_j\) is drawn from \(p(\cdot | \theta _{1,j}, \mathcal {M}_1)\) and \(\theta _{1,j}\) is drawn from \(p(\cdot | \mathcal {M}_1)\), and accordingly \(x_l \sim p(\cdot | \theta _{2,l}, \mathcal {M}_2)\) and \(\theta _{1,j} \sim p(\cdot | \mathcal {M}_2)\). J and L are the total numbers of Monte Carlo simulations used for the respective models. The terms in denominator and numerator are thus equal to the rate at which parameter samples drawn at random from the prior of the respective model are accepted, i.e., yield model output that is closer to the data than \(\epsilon\). The tolerance \(\epsilon\) is a trade-off, which should be chosen as small as possible for a good approximation, but large enough so that a sufficient number of parameter samples with \(I_{B_{\epsilon }(D)}(x_j) = 1\) can be generated in feasible computing time.

Instead of a scalar metric \(\rho\) and tolerance \(\epsilon\), we use the vector of summary statistics \(\underline{s}(x,D)\) introduced in the previous section, and a separate tolerance \(\epsilon _k\) for each component \(s_k\). The indicator function \(I_{B_{\epsilon }(D)}\) to accept parameter samples then operates on the set

Note that in the limit \(\epsilon \rightarrow 0\) the approximations of posterior distribution and Bayes factor only converge to the exact Bayesian results if the summary statistics that define the metric are sufficient, i.e., if they carry as much information about the parameter of a model as the full model output x does. Only in very few cases this can be guaranteed, and thus one has to hope that the approximation is still good, given that one chooses summary statistics that are highly informative about the model parameters. On the other hand, we can view the results as an approximation to exact Bayesian inference and model comparison based not on the actual data D but on the observed statistics of D, which mirrors our approach to the specific problem.

Sampling parameters from the prior distribution in order to obtain the posterior is typically inefficient, since most of the prior parameter space has very small posterior probability. Instead we use an approach known as ABC population Monte Carlo (ABC-PMC) (Beaumont et al. 2009), which uses sequential importance sampling to approximate the posterior distribution through a sequence of intermediary distributions using decreasing values for the tolerances \(\epsilon _k\). In this approach, we start at some relatively large tolerance and draw parameter samples from the prior distribution \(p(\theta )\) until a desired number of samples have satisfied \(s_k(x,D)<\epsilon _k\). This population of parameters is then perturbed by a Gaussian kernel and sampled from in the next iteration with slightly lower tolerance. This perturbed distribution is referred to as the proposal distribution \(f(\theta )\). From the second iteration on, the population of accepted parameter samples has to be weighted according to importance sampling in order to compensate that it was not drawn from the prior distribution but from the proposal distribution. The weights of a particle j in importance sampling is given by the likelihood ratio of prior and proposal distribution \(w_j = \frac{p(\theta _j)}{f(\theta _j)}\).

Furthermore, in ABC-PMC the Gaussian kernel used to perturb the previous population is adaptive at each iteration. Beaumont et al. (2009) use a diagonal multivariate Gaussian kernel where the diagonal entries of the covariance matrix are given by the two-fold variance of the population samples of the previous iteration, weighted by the importance weights introduced above. Instead, we use a multivariate Gaussian kernel with a covariance matrix given by the weighted covariance matrix of the previous population multiplied by 2. This allows us to sample more efficiently when there is co-variant structure in the parameter posterior, as shown later. We stop the iterative procedure when the tolerances are so low that it is computationally very expensive to get a reasonable amount of posterior samples. In this study, computations have been performed on a personal desktop computer and obtaining 500 posterior parameter samples at the lowest tolerance required up to 20 million model simulations. The algorithm used in this study to obtain parameter posteriors and Bayes factors is explained in the “Appendix”.

An important choice to be made in Bayesian inference and model comparison are the prior parameter distributions. While the posterior distributions are relatively robust to changes in the priors if the latter are sufficiently flat, Bayes factors can behave more sensitively. We aim to use uninformative priors, i.e. priors that are as objective as possible and reflect that we do not have any a priori knowledge about likely parameter values in our models, except for the signs of certain parameters. Since for the models used in this study we cannot derive priors that are strictly uninformative in terms of certain criteria, such as Jeffrey’s priors or Bernardo’s reference priors, we choose diffuse uniform priors due to their flatness.

It is worthwhile to note that because of the use of summary statistics there is no point to point model output and data comparison and thus we can use a length of model simulations different to the data length. Increasing model simulation length can sometimes increase performance, as will be discussed later.

4 Results

In order to demonstrate the method’s abilities, we first apply it to synthetic data from within our model ensemble in Sect. 4.1. Thereafter, we present the results of the method when applied to the NGRIP data set in Sect. 4.2.

4.1 Synthetic data study

As synthetic data, we choose a 87 kyr simulation output from the VDP model in a dynamical regime of noisy oscillations, which can be seen in Fig. 4. With this we demonstrate the following abilities of our method: (1) The correct model parameters are recovered from the posterior parameter distribution of the true model. (2) The true model is selected very strongly over a model which cannot operate in a comparable dynamical regime. (3) A model that can operate in the same dynamical regime as the true model but is of higher complexity is disfavored by the model selection procedure due to the higher number of parameters. (4) The results of model and parameter inference at sufficiently low tolerance are not critically dependent on data length and parameter prior distributions.

The model comparison parameters used in this synthetic data study are as follows. Each model simulation output was equally long as the data (87 kyr), and a total number of 500 particles were used at each step. The prior parameter distributions for all models were chosen to be uniform. We used 15 ABC-PMC iterations with descending tolerances as specified in Table 1, which were chosen empirically such that no single tolerance \(\epsilon _k\) limits the acceptance of parameter samples at a given iteration. The tolerances need to be adjusted individually, because the individual summary statistics \(s_k\) that make up the state space metric have different ranges. This procedure is certainly not unique, and thus some results might change if different choices in the metric are made, which is a well-known issue in ABC.

Violin plot illustrating the convergence of VDP marginal intermediate distributions for increasing iterations of the ABC-PMC algorithm. For each iteration, a Gaussian kernel estimate of the density is shown, together with the median. The true parameter values are indicated with a green dashed line. The bounds of the uniform distributions on the prior are indicated with the red lines

4.1.1 Parameter inference

We first discuss the results for parameter inference, starting with the true model. In the violin plot of Fig. 5, we show the kernel density estimates of the VDP intermediate marginal parameter distributions for each iteration and indicate the bounds of the uniform prior distributions (red). We observe a gradual decrease in dispersion of the distributions as well as a convergence of the medians close to the true values. Figure 6a shows in more detail the marginal posterior parameter distributions for the VDP model after the last iteration. We can see that there remains both an uncertainty in the parameter estimate as well as a small bias of the distribution mode for some parameters. The uncertainty is mostly due to the non-zero tolerance and short simulation length, while the bias is due to random sampling and shortness of the test data. We conducted experiments with various data and model simulation lengths: When using shorter data length, the summary statistics are always quite different from the mean model statistics. Thus we find a bias in the inferred parameters. Longer data yields statistics closer to the model mean and thus less biased inference. However, the posterior dispersion does not change. If we increase the model simulation length, we can reduce the posterior dispersion because the statistics of model output samples are sharper for a given parameter and thus less wrong parameter samples scatter into the posterior. The Bayes factors are not systematically influenced in either case.

We furthermore observe that some parameters are better constrained by our summary statistics than others and are thus easier to infer, such as can be seen for c in contrast to b. Additionally, while most parameters seem independent of each other, the parameters \(a_1\) and \(a_3\) show a linear dependency in the posterior, which can be seen in the right-most panel of Fig. 6a. This gives rise to most of the uncertainty seen in the marginal posteriors.

Gaussian kernel density estimates of the marginal posterior distribution of a VDP and b FHN model parameters as obtained after the last iteration of ABC-SMC on synthetic data. The gray dashed lines indicated the true parameter values, and the red lines indicate the uniform prior distributions. In the right-most panel of a we show the two-dimensional marginal distribution of parameters \(a_1\) and \(a_3\) for the VDP model

The parameter inference results for the FHN model are shown in Fig. 6b. We see that parameters, which the FHN model has in common with the VDP model, also converge to the true values. The additional parameter \(\beta\) stays quite uncertain but has most weight in a region close to 0, which would then correspond to the VDP model. We do not show marginal posterior parameter distributions for the DW model, since it is eliminated by our model selection procedure after iteration 6, as discussed in the following.

4.1.2 Model comparison

We now discuss model comparison results. In Fig. 7 we show Bayes factors for four different ABC experiments at all iterations. The data from the experiment discussed in the previous section are shown in circle markers. The Bayes factors of the DW model over the VDP model, shown in Fig. 7a, drop to zero already at large tolerances, which means that the ABC procedure can efficiently exclude the wrong model. In contrast, Fig. 7b shows that the Bayes factors of the FHN model over the VDP model settles after some fluctuations to \(B_{FHN,VDP}\approx 0.5\) as the tolerance approaches zero. This is because the two models are nested, i.e. the FHN model includes the VDP model but has an additional parameter. We can thus use this Bayes factor as an estimate of how much an additional parameter is penalized among models explaining the data equally well.

The squares in Fig. 7 show an ABC experiment where we doubled the prior range of the parameters b and \(a_1\) in the VDP model. It is seen that the model comparison results do not depend on the width of the priors, given they are wide enough to contain the full posterior distribution. In the third ABC experiment, marked with triangles, we used a synthetic data length of 1000 kyr. The last experiment is marked with diamonds and shows results for using a longer simulation length of 435 kyr. In both of these experiments the model comparison results do not change qualitatively.

4.2 NGRIP data study

The ABC-PMC runs with NGRIP data were performed with the sequence of tolerances given in Table 2. Because none of the models can perfectly reproduce the NGRIP statistics, we had to stop the sequential algorithm due to computational demand at slightly higher tolerances compared to the synthetic data study. As in the synthetic data study, we used uniform priors for all parameters. The ranges of these priors can be seen in the respective figures showing the posterior distributions (Figs. 8, 9 and 10) and were chosen wide enough to contain the full posterior distribution.

4.2.1 Parameter inference

The posterior distributions of the DW model (\(b=0\)) are shown in Fig. 8 and lie well constrained within the priors. There remains considerable dispersion in the marginals of \(a_1\) and \(a_3\), most of which comes from a linear dependency of the two, as can be seen in the bottom right panel of the figure. With \(a_0\) close to zero, the double well potential inferred from the data is approximately symmetric.

We now discuss the inferred dynamics of the oscillator models when only including noise in the x variable, i.e., \(\sigma _Y=0\). The posterior distributions are shown in Fig. 9. Because different regions in parameter space describe different dynamical regimes, we analyze the posterior samples as an ensemble. In the posterior samples of the VDP shown in Fig. 9a, we can see that the distribution of b is approaching 0. Thus the dynamics are effectively one-dimensional and approximate a symmetric double well potential, as discussed in Sect. 2. Still, 91% of the posterior samples are in a regime of noisy oscillations, because |c| is too small compared to the ratio \(a_1/a_3\). However, the oscillation periods expected from the deterministic system increase as b goes to zero and are much longer than the waiting times of the stochastic dynamics. The median ratio of deterministic period to stochastic waiting time is 38.4, with 10- and 90-percentiles at 8.2 and 165.1. Thus, the dynamics are such that much time can be spent on each branch of slow manifold, which is then escaped via noise. In effect, the model is noise dominated and the dynamics are closely similar to a double well potential.

Figure 9b shows the posterior distributions of the FHN model. We observe that b again becomes close to zero, albeit not as strongly as in the VDP model. Additionally, \(\beta\) approaches its limit of \(-\pi /2\). The combination of these two parameter regimes typically yields two stable steady states, as explained in Sect. 2. Indeed, 95% of the posterior samples are in a bi-stable regime, whereas the remaining ones are in the excitable regime. The dynamics in the x variable in a bi-stable regime are again effectively very similar to double well potential dynamics. There is a large remaining dispersion in c, since the effect of c on the dynamics becomes negligible as \(\beta\) approaches \(-\pi /2\).

As we include noise in the y variables of the oscillator models, the inferred parameter regimes change as seen from the marginal distributions in Fig. 10. In the VDP\(_Y\) model, the parameter b no longer tends to zero. As a result, the dynamics are no longer quasi one-dimensional. Out of the posterior samples, 83% are in an oscillatory regime, the rest being excitable. Within the oscillatory samples, the median ratio of deterministic period to stochastic waiting time is 1.02 (10- and 90-percentile at 0.73 and 1.75). Due to the parameter \(a_1\) approaching very small values, the amplitude of the deterministic limit cycles is small compared to the amplitude of the noisy signal. Thus, the dynamics are again very noise-driven and apart from the mean period do not inherit any features of the deterministic system. For the FHN model, Fig. 10b shows that the parameters b and \(\beta\) no longer approach their boundaries of 0 and \(\pi /2\), respectively. As a result, the FHN\(_Y\) model posterior samples contain 79% mono-stable, 17% oscillatory and 4% bi-stable parameter regimes. Thus, the excitable regime is the most prevalent. It does not seem to matter, whether the single fixed point in the mono-stable samples is in the ’warm’ or ’cold’ state, as they are roughly equally distributed among the ensemble. Furthermore, as for the VDP model, the parameter \(a_1\) tends to very small values.

To get an idea of the maximum likelihood parameters of our models and to show representative time series, we estimate the parameter sample which lies in the highest density region of the posterior distribution. This is done via Gaussian kernel smoothing, where the kernel width is chosen manually. Although the method is typically robust over a wide range of kernel widths, the result still has to be taken with care because of the relative sparseness of the posterior samples in parameter space. This is especially true if parameter samples tend to accumulate at the edges of their valid domain, as is often the case in our study. The resulting parameter estimates are given in Table 3 and model realizations are shown together with the data in Fig. 11.

a NGRIP data set used as basis of our study. b–f Model realizations of all models considered in the study with highest posterior probability parameters from Table 3. b–f correspond to the DW, VDP, FHN, VDP\(_Y\) and FHN\(_Y\) models, respectively

4.2.2 Model comparison

As detailed in Sect. 3.3, the ratio of acceptance rates in ABC-PMC runs of two models at a given tolerance gives our approximation of the Bayes factor \(\mathcal {B}_{1,2}\). The results are summarized in the Table 4. As can be seen in the table’s first column, the DW model is slightly preferred over the oscillator models without noise in the y variable, while the converse is true as we add noise to both variables. Thus, the performance of the oscillators clearly improves by adding noise also to the y-variable, which is reflected by Bayes factors of 6.27 and 4.83 for the VDP\(_Y\) over VDP and FHN\(_Y\) over FHN models, respectively. Comparing the two oscillator models with and without noise in the y variable, we observe that in both cases the FHN model is very slightly preferred with Bayes factors of 1.24 and 1.61, respectively. As a result, the model that is most supported by the data in terms of the summary statistics chosen by us is the FHN\(_Y\) model with additive noise in both variables.

4.2.3 Time reversal asymmetry

We now address the characteristic saw-tooth shape of the DO events, which is not accounted for by the summary statistics used in the model comparison experiments of this study so far. On average, the NGRIP record rises much faster to high values during warming periods as it falls to low values during cooling periods. This feature is often referred to as time-reversal asymmetry and can be measured in a time series x(t) by the skewed difference statistic

where \(\langle \cdot \rangle\) denotes the expectation value over the time series and \(\tau\) corresponds to a characteristic time scale [see e.g. Theiler et al. (1992)]. A similar indicator has been used before to analyze the results of the model comparison study by Kwasniok (2013). In contrast to the DW model, both VDP and FHN models can in principle show such time reversal asymmetry, in a regime of relaxation oscillations. Due to similarity in shape of the DO events and relaxation oscillations, the latter are often invoked as plausible dynamical mechanism.

Time-reversal asymmetry statistic \(M(\tau )\) for the NGRIP data (red) and model averages over the posterior samples from ABC-PMC runs with following summary statistics: 1. \(s_{1,2,3,4,5,6}\) (blue). 2. \(s_{1,2,3,4,5}\) (orange dashed). 3. \(s_6\) and standard deviation (green). For the former two runs, 95% simultaneous confidence bands are shown. Two example realizations of the first run are shown in gray

In order to test whether the oscillator models can show asymmetry behavior similar to the NGRIP time series, we include the RMSD of \(M(\tau )\) up to a lag of \(\tau =2500\) years for model output and data as an additional summary statistic \(s_6\). The RMSD of the data curve \(M(\tau )\) to a straight line, i.e., a model with no asymmetry, is 0.92, which serves as a baseline for our asymmetry summary statistic \(s_6\) and respective tolerance \(\epsilon _6\). We restrict our analysis to the FHN\(_Y\) model since it has the richest dynamics.

In Fig. 12 we compare \(M(\tau )\) of data, and FHN\(_Y\) posterior samples of different ABC runs. For illustrative purposes, we conducted a ABC-PMC run that only used \(s_6\) and the standard deviation as summary statistics. The average model statistics for posterior samples obtained from this run are shown as a green line in the figure and demonstrate that the FHN\(_Y\) model has a dynamical regime with asymmetry of the desired magnitude. Next, we performed a ABC-PMC run with all six summaries \(s_{1,2,3,4,5,6}\). We gradually decreased the tolerance of \(s_6\) from \(\epsilon _6=0.8\) to \(\epsilon _6=0.575\), while lowering the other tolerances to the rather moderate values of \(\epsilon _{1,2,3}=0.225\) and \(\epsilon _{4,5}=0.15\). At this point it becomes computationally very expensive to continue with lower tolerances, mirroring the fact that the FHN\(_Y\) model cannot both display time reversal asymmetry and the statistical behavior discussed earlier in this work. The summaries \(s_{1,2,3,4,5}\) force the oscillator model into a regime, where it can only show asymmetry throughout a whole realization by chance, which is very rare. From the figure we can see that on average, the posterior samples of the run that included \(s_6\) show no asymmetry. The same holds for the posterior samples inferred from the ABC-PMC run without \(s_6\). The posterior samples with \(s_6\) are also only marginally more likely to show significant asymmetry compared to the ones without \(s_6\), as can be seen from the confidence bands.

5 Discussion and conclusion

This study presents Bayesian model comparison experiments of stochastic dynamical systems given the NGRIP \(\delta ^{18}\)O record of the last glacial period, and aims to further the knowledge on which dynamical mechanism underlies DO events. The highly stochastic nature of these climate changes, as well as of the underlying data set prompted us to base this model comparison solely on statistical properties of the time series, captured by summary statistics. This approach is different from previous model comparison studies concerned with Greenland ice core data and stochastic dynamical systems (Kwasniok 2013; Krumscheid et al. 2015; Mitsui and Crucifix 2017; Boers et al. 2017). Even though these studies also aim to compare different models in terms of their statistical properties, such as stationary densities and mean waiting times, they first estimate maximum-likelihood parameters from the 1-step prediction error with various techniques and subsequently use the Bayesian Information Criterion for model selection. Afterwards, they qualitatively compare the statistical properties of the best fit models. However, it is unclear how the statistical properties of the models emerge in the fitting procedure. As a consequence, there might arise a mismatch in between the models or parameter regimes preferred by the model comparison procedure and by qualitative analysis of the statistical properties, as reported by Boers et al. (2017). This motivates us to base the entire parameter inference and model comparison on summary statistics. Additionally, our approach is different in that we are able to show full parameter posterior distributions, which allows the assessment of parameter sensitivity and uncertainty. This becomes especially important in models with physically motivated parameters.

As prerequisite result, using synthetic data, we demonstrated in Sect. 4.1 how parameter inference and model comparison can be successfully done with a set of summary statistics and the ensemble of models considered. For this purpose, we adopted a version of ABC to our needs, and showed that given a model realization from within the model ensemble, the true model and its parameters can be inferred in a robust way. Furthermore, we estimated the penalty on the Bayes factor arising if one model of our ensemble has a superfluous parameter. In the case of two models being both correct, we yield \(\mathcal {B}\approx 2\) in favor of the model without the superfluous parameter, which we consider to be only a small penalty.

We subsequently applied the model comparison framework to the NGRIP data set, mainly aiming to establish evidence in favor or against the DW model over one or both of the oscillator models. We found that the results depend on whether one includes noise only in the observed x variable of the oscillators, or in both. There is evidence that the DW model is better supported by the data than the oscillator models without noise in the y variable. Our estimate of the Bayes factor in favor of the DW model over the VDP and FHN models is 3.87 and 2.41, respectively. By looking at the posterior parameter distributions, we can see that the oscillator models in fact operate in regimes where they approximate dynamics similar to the DW model. Specifically, the VDP oscillator dynamics can be characterized by deterministic oscillations with very long residences in either of the two branches of the slow manifold, which are however abandoned prematurely by a stochastic jump to the other branch. The FHN model, on the other hand, operates in a bi-stable regime, where transitions are noise-induced. As a consequence, we believe that in the case of \(\sigma _Y=0\) there is a large contribution to the Bayes factors by a penalty on the additional parameters of the oscillator models. Even though the Bayes factors are not very high, we can thus conclude that the double well potential paradigm is clearly favored over oscillator models with additive noise only in the x variable.

As we add noise to the y variable of the oscillator models, we saw clear improvement over the case with \(\sigma _Y=0\), as inferred from Bayes factors of 6.27 and 4.83 for the VDP and FHN model, respectively. We inferred from the posterior parameter distributions that the oscillator models now operate in dynamical regimes different from the case \(\sigma _Y=0\). While the VDP model still is in an oscillatory regime, albeit with different properties, the FHN model now prefers an excitable regime with one fixed point either in a ’warm’ or ’cold’ state. From the Bayes factors of 1.62 and 2.01 we now find slight evidence in favor of the VDP\(_Y\) and FHN\(_Y\) models over the DW model. As a consequence, our results agree in principle with previous model comparison studies that also compare a DW potential model with a VDP oscillator including additive noise in both variables (Kwasniok 2013; Mitsui and Crucifix 2017). However, while these studies find quantitatively overwhelming evidence in favor of the oscillator, we only find very mild evidence. To complement our quantitative analysis via Bayes factors, one can qualitatively observe the models’ statistical properties underlying our summary statistics. We show this in the Electronic supplementary material for both best fit parameter estimates and posterior parameter ensemble averages. We conclude that none of the models can fit all statistics at the same time in a robust way. Furthermore, the different models don’t fit the individual statistics equally well. Although there might be a slight overall advantage for the FHN\(_Y\) model, our analysis does not suggest that either one of the DW, VDP\(_Y\) and FHN\(_Y\) models is much worse than the others in describing the statistical properties of the record.

Finally, we considered an additional summary statistic in our Bayesian model comparison experiment, which measures the time reversal asymmetry of a time series and captures the characteristic saw-tooth shape of the DO events. We used this additional statistic in a ABC-PMC run on the FHN model, which can show time reversal asymmetry in a regime of relaxation oscillations. We observe that it is not possible to yield time reversal asymmetry comparable to the data in the model when also obeying constraints posed by the other statistical properties \(s_{1,2,3,4,5}\), in particular the temporal irregularity of events captured by the long-tailed distributions of waiting times. This is consistent with the results of the study by Kwasniok (2013), where it is observed that the best-fit VDP model inferred from the NGRIP data also does not show time-reversal asymmetry. We thus conclude that the time-asymmetry of the record cannot be explained by chance. It is a real feature of the data, which is not captured by the simple class of models investigated here. More complex models are necessary, such as models including time delays, which were shown to yield time-reversal asymmetry to a certain degree when inferred from the NGRIP data (Boers et al. 2017).

Our study does not address external forcing directly, since we use summary statistics based on stationary properties only. This can however readily be done by including summary statistics of time-varying properties in the data, such as the summary statistics used in Lohmann and Ditlevsen (2018). Even though there is evidence for a contribution of external modulation to the statistical properties in the record (Mitsui and Crucifix 2017; Lohmann and Ditlevsen 2018), we still find it useful to analyze a class of models that can approximate the observed statistics without a forced modulation of parameters. We believe that the observed statistical properties are largely due to stationary variability and not external modulation.

In conclusion, this study investigates the ability of a class of models to explain the statistical properties of the glacial climate. This class of models incorporates different dynamical paradigms, which can be interpolated by continuous changes of parameters. We conducted model comparison experiments using only key statistical properties of the data. Although we find that relaxation oscillator models with noise in both variables have a slight advantage over stochastic motion in a double well potential, the Bayes factors are not very conclusive. None of the models can accurately fit all data statistics and all models have to rely heavily on chance for a realization to fit closely. This means that the dynamics of simple stochastic dynamical systems inferred from the glacial climate record must be noise-dominated and the deterministic backbone is less well-defined. As a result, different deterministic regimes from the spectrum in between double well potential and relaxation oscillations can be equally consistent with the data.

References

Beaumont MA, Cornuet JM, Marin JM, Robert CP (2009) Adaptive approximate Bayesian computation. Biometrika 96(4):983–990

Boers N, Chekroun MD, Liu H, Kondrashov D, Rousseau DD, Svensson A, Bigler M, Ghil M (2017) Inverse stochastic-dynamic models for high-resolution Greenland ice core records. Earth Syst Dyn 8:1171–1190

Cessi P (1994) A simple box model of stochastically forced thermohaline flow. Phys Oceanogr 24:1911

Dansgaard W et al (1993) Evidence for general instability of past climate from a 250-kyr ice-core record. Nature 364:218

Ditlevsen PD (1999) Observation of \(\alpha\)-stable noise induced millenial climate changes from an ice-core record. Geophys Res Lett 26(10):1441–1444

Ditlevsen PD, Andersen KK, Svensson A (2007) The DO-climate events are probably noise induced: statistical investigation of the claimed 1470 years cycle. Clim Past 3:129–134

Drijfhout S, Gleeson E, Dijkstra HA, Livina V (2013) Spontaneous abrupt climate change due to an atmospheric blocking-sea-ice-ocean feedback in an unforced climate model simulation. PNAS 110(49):19713–19718

Kleppin H, Jochum M, Otto-Bliesner B, Shields CA, Yeager S (2015) Stochastic atmospheric forcing as a cause of greenland climate transitions. J Clim 28:7741–7763

Krumscheid S, Pradas M, Pavliotis GA, Kalliadasis S (2015) Data-driven coarse graining in action: modeling and prediction of complex systems. Phys Rev E 92:042139

Kwasniok F (2013) Analysis and modelling of glacial climate transitions using simple dynamical systems. Philos Trans R Soc A 371:20110472

Kwasniok F, Lohmann G (2009) Deriving dynamical models from paleoclimatic records: application to glacial millennial-scale climate variability. Phys Rev E 80:066104

Lohmann J, Ditlevsen PD (2018) Random and externally controlled occurrences of Dansgaard–Oeschger events. Clim Past 14(5):609–617

Marin JM, Pudlo P, Robert CP, Ryder RJ (2012) Approximate Bayesian computational methods. Stat Comput 22:1167–1180

Mitsui T, Crucifix M (2017) Influence of external forcings on abrupt millennialscale climate changes: a statistical modelling study. Clim Dyn 48:2729

Münch T, Kipfstuhl S, Freitag J, Mayer H, Laepple T (2016) Regional climate signal vs. local noise: a two-dimensional view of water isotopes in Antarctic firn at Kohnen Station, Dronning Maud Land. Clim Past1 12:1565–1581

Pritchard JK, Seielstad MT, Perez-Lezaun A, Feldman MW (1999) Population growth of human Y chromosomes: a study of Y chromosome microsatellites. Mol Biol Evol 16(12):1791–8

Rasmussen SO (2014) A stratigraphic framework for abrupt climatic changes during the Last Glacial period based on three synchronized Greenland ice-core records: refining and extending the INTIMATE event stratigraphy. Q Sci Rev 106:14–28

Roberts A, Saha R (2016) Relaxation oscillations in an idealized ocean circulation model. Clim Dyn 48(7):2123–2134

Rocsoreanu C, Georgescu A, Giurgiteanu N (2000) Mathematical modelling: theory and applications, vol 10. Springer, Berlin

Rypdal M, Rypdal K (2016) Late Quaternary temperature variability described as abrupt transitions on a 1/f noise background. Earth Syst Dyn 7:281–293

Stommel H (1961) Thermohahe convection with two stable regimes of flow. Tellus 13:2

Stommel HM, Young WR (1993) The average T-S relation of a stochastically forced box model. Phys Oceanogr 23:151–158

Theiler J, Eubank S, Longtin A, Galdrikian B, Farmer JD (1992) Testing for nonlinearity in time series: the method of surrogate data. Phys D 58:77–94

Timmermann A, Lohmann G (2000) Noise-induced transitions in a simplified model of the thermohaline circulation. Phys Oceanogr 30:1891–1900

Acknowledgements

This project has received funding from the European Unions Horizon 2020 research and innovation Programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie Grant agreement No 643073.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix: ABC-PMC algorithm

Appendix: ABC-PMC algorithm

In this appendix we present our adaption of the ABC-PMC algorithm first presented in Beaumont et al. (2009). It is an iterative procedure over subsequent populations t of N parameter samples \(\theta _t^{j}\), called particles in the following. Each population is weighted by importance sampling weights \(w_t^j\), which are the likelihood ratios of the prior parameter distribution \(p(\theta _t^{j})\) and the proposal distribution. The proposal distribution is a perturbation of the previous population by a Gaussian kernel \(K_t(\cdot |\theta )\), whose kernel width adapts after every population t. As discussed in Sec. 3, \(\underline{s}(D',D)\) is a vector of summary statistics, and \(\underline{\epsilon }_t\) is a vector of tolerances, whose entries decrease for increasing population t.

-

1.

Set population indicator \(t=0\)

-

2.

Set particle indicator \(j=1\)

-

3.

If \(t=0\) sample \(\theta ^{**}\) from \(p(\cdot )\).

If \(t>0\) sample \(\theta ^{*}\) from previous population with weights \(\{ w_{t-1}^j \}\) and perturb particle to obtain \(\theta ^{**} \sim K_t(\cdot |\theta ^*)\), where \(K_t\) is a Gaussian kernel with covariance \(\Sigma _{t-1}\).

If \(p(\theta ^{**})=0\) return to 3.

Simulate data \(D '\) from \(p(\cdot |\theta ^{**})\).

If \(\underline{s}(D',D)>\underline{\epsilon }_t\) return to 3.

-

4.

Set \(\theta _t^{j} = \theta ^{**}\) and calculate the particle weight \(w_t^j = \frac{p(\theta _t^{j})}{\sum _{i=1}^N w_{t-1}^i K_t(\theta _{t-1}^i)|\theta _t^{j}))}\)

If \(j<N\), set \(j=j+1\) and go to 3.

-

5.

Normalize weights and set \(\Sigma _t\) to twice the covariance of \(\{ \theta _t^j \}\)

If \(t<T\) set \(t=t+1\) and go to 2.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Lohmann, J., Ditlevsen, P.D. A consistent statistical model selection for abrupt glacial climate changes. Clim Dyn 52, 6411–6426 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-018-4519-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-018-4519-2