Abstract

Background

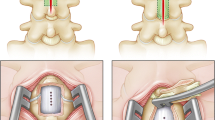

Cord retethering and other postoperative complications can occur after the surgical untethering of a first-time symptomatic tethered cord. It is unclear if using duraplasty vs. primary dural closure in the initial operation is associated with decreased incidence of either immediate postoperative complications or subsequent symptomatic retethering. It is also unclear if different etiologies are associated with different outcomes after each method of closure. We reviewed our pediatric experience in first-time surgical untethering of symptomatic tethered cord syndrome (TCS) to identify the incidence of postoperative complications and symptomatic retethering after duraplasty vs. primary closure.

Materials and methods

We retrospectively reviewed 110 consecutive pediatric (<18 years old) cases of first-time symptomatic spinal cord untethering at our institution over a 10-year period. Incidence of postoperative complications and symptomatic retethering were compared in cases with duraplasty vs. primary dural closure use.

Results

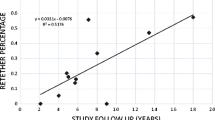

Mean age was 5.7 ± 4.8 years old. “Complex” etiologies included lipomyelomeningocele or prior lipomyelomeningocele repair in 22 (20%) patients, prior myelomeningocele repair in 35 (32%), and concurrent lumbosacral lipoma in 18 (16%). “Noncomplex etiologies” included fatty filum in 26 (24%) and split cord malformation in five (4%). Seventy-five (68%) cases underwent primary dural closure vs. 35 (32%) with duraplasty. Twenty-nine (26%) patients experienced symptomatic retethering at a median [interquartile range (IQR)] of 30.5 [20.75–41.75] months postoperatively. There was no difference in incidence of postoperative cerebrospinal fluid leak, surgical site infection, or median [IQR] length of stay in patients receiving primary dural closure [4 (5%), 7 (9%), and 5 (4–6) days, respectively] vs. duraplasty [3 (9%), 3 (9%), and 6 [5–8] days, respectively], p > 0.05. Complex etiologies were more likely to retether than noncomplex etiologies after primary closure (33.6% vs. 6.6%, p = 0.05) but not after duraplasty (13.7% vs. 5.4%, p = 0.33). Duraplasty graft type (polytetrafluoroethylene vs. bovine pericardium) was not associated with pseudomeningocele or retethering.

Conclusion

In our experience, the increased rate of symptomatic retethering observed with complex pediatric TCS (pTCS) etiologies after primary dural closures was not observed when duraplasty was instituted. Expansile duraplasty may be valuable specifically in the management of patient subgroups with complex pTCS etiologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Aliredjo RP, de Vries J, Menovsky T, Grotenhuis JA, Merx J (1999) The use of Gore-Tex membrane for adhesion prevention in tethered spinal cord surgery: technical case reports. Neurosurgery 44:674–677 discussion 677-678

Bui CJ, Tubbs RS, Oakes WJ (2007) Tethered cord syndrome in children: a review. Neurosurg Focus 23:1–9

Chapman PH (1982) Congenital intraspinal lipomas: anatomic considerations and surgical treatment. Child Brain 9:37–47

Cochrane DD (2007) Cord untethering for lipomyelomeningocele: expectation after surgery. Neurosurg Focus 23:1–7

Durham SR, Fjeld-Olenec K (2008) Comparison of posterior fossa decompression with and without duraplasty for the surgical treatment of Chiari malformation Type I in pediatric patients: a meta-analysis. J Neurosurg Pediatr 2:42–49

Filippi R, Schwarz M, Voth D, Reisch R, Grunert P, Perneczky A (2001) Bovine pericardium for duraplasty: clinical results in 32 patients. Neurosurg Rev 24:103–107

Garceau GJ (1953) The filum terminale syndrome (the cord-traction syndrome). J Bone Jt Surg 35-A:711–716

Haro H, Komori H, Okawa A, Kawabata S, Shinomiya K (2004) Long-term outcomes of surgical treatment for tethered cord syndrome. J Spinal Disord Tech 17:16–20

Hoffman HJ, Hendrick EB, Humphreys RP (1976) The tethered spinal cord: its protean manifestations, diagnosis and surgical correction. Child Brain 2:145–155

Inoue HK, Kobayashi S, Ohbayashi K, Kohga H, Nakamura M (1994) Treatment and prevention of tethered and retethered spinal cord using a Gore-Tex surgical membrane. J Neurosurg 80:689–693

Kang JK, Lee KS, Jeun SS, Lee IW, Kim MC (2003) Role of surgery for maintaining urological function and prevention of retethering in the treatment of lipomeningomyelocele: experience recorded in 75 lipomeningomyelocele patients. Childs Nerv Syst 19:23–29

Kaplan E, Meier P (1958) Non parametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Amer Stat Assoc 53:457–481

Lew SM, Kothbauer KF (2007) Tethered cord syndrome: an updated review. Pediatr Neurosurg 43:236–248

McCormick PC, Stein BM (1990) Intramedullary tumors in adults. Neurosurg Clin N Am 1:609–630

Munshi I, Frim D, Stine-Reyes R, Weir BK, Hekmatpanah J, Brown F (2000) Effects of posterior fossa decompression with and without duraplasty on Chiari malformation-associated hydromyelia. Neurosurgery 46:1384–1389 discussion 1389-1390

Muthukumar N, Subramaniam B, Gnanaseelan T, Rathinam R, Thiruthavadoss A (2000) Tethered cord syndrome in children with anorectal malformations. J Neurosurg 92:626–630

Pang D, Wilberger JE Jr (1982) Tethered cord syndrome in adults. J Neurosurg 57:32–47

Pierre-Kahn A, Zerah M, Renier D, Cinalli G, Sainte-Rose C, Lellouch-Tubiana A, Brunelle F, Le Merrer M, Giudicelli Y, Pichon J, Kleinknecht B, Nataf F (1997) Congenital lumbosacral lipomas. Childs Nerv Syst 13:298–334 discussion 335

Selden NR (2006) Occult tethered cord syndrome: the case for surgery. J Neurosurg 104:302–304

Tubbs RS, Oakes WJ (2006) A simple method to deter retethering in patients with spinal dysraphism. Childs Nerv Syst 22:715–716

Yamada S, Zinke DE, Sanders D (1981) Pathophysiology of “tethered cord syndrome”. J Neurosurg 54:494–503

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Samuels, R., McGirt, M.J., Attenello, F.J. et al. Incidence of symptomatic retethering after surgical management of pediatric tethered cord syndrome with or without duraplasty. Childs Nerv Syst 25, 1085–1089 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-009-0895-6

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-009-0895-6