Abstract

Plant growth regulators play a key role in cell wall structure and chemistry of woody plants. Understanding of these regulatory signals is important in advanced research on wood quality improvement in trees. The present study is aimed to investigate the influence of exogenous application of 24-epibrassinolide (EBR) and brassinosteroid inhibitor, brassinazole (BRZ) on wood formation and spatial distribution of cell wall polymers in the xylem tissue of Leucaena leucocephala using light and immuno electron microscopy methods. Brassinazole caused a decrease in cambial activity, xylem differentiation, length and width of fibres, vessel element width and radial extent of xylem suggesting brassinosteroid inhibition has a concomitant impact on cell elongation, expansion and secondary wall deposition. Histochemical studies of 24-epibrassinolide treated plants showed an increase in syringyl lignin content in the xylem cell walls. Fluorescence microscopy and transmission electron microscopy studies revealed the inhomogenous pattern of lignin distribution in the cell corners and middle lamellae region of BRZ treated plants. Immunolocalization studies using LM10 and LM 11 antibodies have shown a drastic change in the micro-distribution pattern of less substituted and highly substituted xylans in the xylem fibres of plants treated with EBR and BRZ. In conclusion, present study demonstrates an important role of brassinosteroid in plant development through regulating xylogenesis and cell wall chemistry in higher plants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Xylogenesis represents one of the dynamic developmental processess by which xylem elements are produced from the vascular meristem [vascular cambium] through a complex coordination of cell division, differentiation, tissue patterning and growth across tissues and organs (Larson 1994; Du et al. 2020). The secondary xylem produced in trees is mainly responsible for providing mechanical support and conduction of water. The tissue composition, structure and chemistry of cell wall are considered to be the major determitants of functional properties of secondary xylem (wood) in higher plants. Understanding the complex mechanism of xylogenesis process is important from scientific, applied and biotechnological perspectives, because biomaterials, such as cellulose and lignin in xylem, represent the prominent part of the terrestrial biomass, and therefore, play an important role in carbon cycle (Boudet et al. 1995). On the other hand, the regulation of vascular development is one of the major unresolved issues of plant developmental biology (Dengler 2001).

Plant hormones have been identified as key regulators in longitudinal and radial growth by influencing cambial acitivity and tissue differentiation process in higher plants (Du et al. 2020). Among these, auxins, gibberellins and cytokinins are reported to play an active role in cell division, elongation and differentiation process (Sharma and Zheng 2019; Camargo et al. 2018; Butto et al. 2020). These hormones are known to maintain a distinct concentration gradients across vascular tissues (Immanen et al. 2016), thus regulating the different stages of secondary growth in plants (Du et al. 2020).

Brassinosteroids (BRs) are plant-specific steroid hormones demonstrated to have an important function in many aspects of plant growth and development (Divi and Krishna 2009; Nolan et al. 2020). These are reported to play a role in photomorphogenesis (Song et al. 2009), leaf angle inclination (Wada et al. 1984), seed germination (Steber and McCourt 2001), leaf senescence and abscission (Fedina et al. 2017), stomatal development (Tae-Wuk et al. 2012), root gravitropism (Retzer et al. 2019), regulation of cell elongation and division (Minami et al. 2019; Liu et al. 2019) and vascular differentiation (Tian et al. 2018). Yamamoto et al. (1997) demonstrated the role of BRs on secondary cell wall formation and cell death during tracheray element differentiation in Zinnia system.

The majority of studies on the regulatory effect of BRs on vascular growth is mainly derived from primary tissue based model systems such as Zinnia and Arabidopsis while the complex biology of secondary growth in woody plants is not yet fully explored (Du et al. 2020). There are a few studies to reveal the role of BRs in various developmental processes of xylogenesis in temperate tree species (Hyunjung et al. 2014; Noh et al. 2015; Gao et al. 2019). It is well known that phytohormonal regulation of xylem differentiation process has a concomitant effect on the structure and chemistry of secondary walls. However, there is little information available on the role of BRs in secondary wall structure and chemistry during secondary xylem formation in tropical species. Therefore, the present study is aimed to investigate the effect of exogenous application of 24-epibrassinolide (EBR) and its inhibition by brassinazole on developmental changes and cell wall chemistry during xylogenesis in L. leucocephala (Fabaceae). L. leucocephala is a tropical, ever green tree species with enormous value for wood which is a promising raw material for paper and pulp industry in India. Hence, the information on hormonal regulation of secondary cell wall structure and chemistry of L. leucocephala wood is necessary for exploring the industrial potential of this plant.

Material and Methods

Plant Material and Treatment

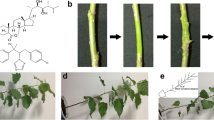

Seeds collected from L. leucocephala growing in the premises of Kerala Agriculture University, Padanekkad campus were selected for the present study. The stock solution (20 µM) of 24-epibrassinolide (EBR) and Brazinazole (BRZ) (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) were prepared by dissolving the powder initially in absolute ethanol and make up final volume with distilled water. For the experiments, EBR was further diluted to the concentrations of 0.2 µM, 1 µM, 2 µM, 3 µM and 4 µM. The dilution of BRZ used in experiment was 0.1 µM, 2 µM, 5 µM, 10 µM and 20 µM. Seeds were soaked in concentrated H2SO4 for 3–5 min for softening the hard seed coat, and then washed with running tap water for 3–4 min. Seeds were allowed to germinate on a filter paper irrigated with different concentrations of EBR. The seedlings measuring 2–3 cm long were transferred to small plastic containers filled with mixture of cocopit and soil. Hormone solutions were added to the soil everyday while distilled water was provided to the control seedlings. L. leucocephala seedlings (control) showed sufficient secondary growth within 30–50 days. After 50 days of treatment, plants were collected and subjected to histological, histochemical and ultrastructural studies.

Light Microscopy

For general histology, samples were fixed in formaldehyde—acetic acid—alcohol (FAA) and embedded in paraffin following routine procedures (Berlyn and Miksche 1976). Transverse sections of 15–20 μm thick taken with a rotary microtome were stained in 1% safranin followed by Astra Blue and finally mounted in DPX after passing through alcohol-xylene series. For histochemical analysis, hand cut transverse sections taken from freshly collected samples were used. For lignin localization, sections were treated with 5% (W/V) phloroglucinol in 10.1 M HCl/ethanol (25/75) (V/V) for 5 min (Vallet et al. 1996). Mäule reaction was used for localizing syringyl lignin units in the cell walls. Sections were left in 1% KMnO4 for 5 min, washed with distilled water, followed by treatment with 1NHCl for 1 min. After washing with distilled water sections were treated with ammonia for 1 min and mounted in 5% glycerol (Mehitsuka and Nakano 1979).

For measuring the length and width of xylem fibers and vessel elements, match stick size stem pieces collected after 50 days of hormonal treatment were macerated in Jeffery’s fluid (1:1 ratio of 10% HNO3 and 10% potassium dichromate). The separated elements were stained with Safranin O and mounted in 50% glycerol. For each parameter, 50 readings were taken from randomly selected elements using an ocular micrometer scale. Statistical analysis of anatomical parameters was performed by the analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s HSD post-hoc test at 0.05 confidence level using JMP 7 program (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

For fluorescence microscopy, fresh hand cut sections stained in 0.1% acriflavine were used to measure the lignin autoflorescence at green excitation (λexc = 510–560 nm). The images were recorded using a Leica DM Epifluorescence microscope with DFC 325 Digital Camera (Germany).

Transmission Electron Microscopy

Suitably trimmed (2 × 5 mm size) stem tissues were fixed in a mixture of 0.1% glutaraldehyde and 4% paraformaldehyde in 50 mM sodium cacodylate buffer for 4 h at room temperature. After washing in buffer, tissues were dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol and embedded in LR white resin (Pramod et al. 2019). For lignin localization, 70–80 nm thick transverse sections were cut with a diamond knife using an ultra-microtome (Ultracut E, Leica, Germany). Sections mounted on nickel grids were stained in 0.1% KMnO4 in citrate buffer for 45 min at room temperature (Donaldson 1992).

For immunogold labelling, 90 nm thick sections were collected on nickel grids. After exposing to buffer ‘A’ (composition: Tris-buffered saline containing 1% bovine serum albumin and 0.1% NaN3, pH 8.2) for 30 min at room temperature, the grids were incubated in LM10 or LM11 antibodies (Plantprobes, UK, 1:20 dilution in buffer A) for 2 days at 4 °C. After three washings with buffer A for 15 min each, the grids were incubated with goat anti-rat secondary antibody labelled with 10-nm colloidal gold particles (BB International, UK) for 2 h at room temperature. For control, sections were incubated only with secondary antibody. Finally, the grids were washed in six changes of buffer ‘A’ for 15 min each, followed by washing in distilled water. All the sections were examined under a transmission electron microscope (TEM, JEOL 1420) at an accelerating voltage of 120 kV.

Results

Effect of EBR and BRZ on Cambial Activity and Xylogenesis

The one month old seedling showed a thick cylinder of secondary xylem surrounded by relatively thin radial layers of secondary phloem (Fig. 1a). The phloem was encircled by patches of pericycle fibres followed by 2–3 layers of cortex, single layer of hypodermis and an outer layer of epidermis. The fusiform initials in the cambial zone showed active periclinal divisions towards both xylem and phloem (Fig. 1b). Secondary xylem was composed of fibres, solitary and radial multiple vessels, ray and apotracheal parenchyma (Fig. 1c).

a–i Transverse sections from the stem of control (a,b,c), EBR treated (d,e,f) and BRZ treated (g,h,i) seedlings of L. leucocephala a One month old seedling showing secondary growth as a thick cylindrical xylem ring b A wide cambial zone (CZ) of control plants with differentiating phloem (on upper side of CZ) and xylem elements (on lower side of CZ) c Xylem showing fibres, parenchyma and thick walled metaxylem tracheary elements (arrow) d Stem showing a thick cylinder of secondary xylem formed following EBR treatment e EBR treated stem showing active cambial zone with differentiating xylem f The secondary xylem of EBR treated stem showing thick walled fibres and vessel elements g BRZ treated stem showing a relatively thin secondary xylem ring and a wide cambial zone h A narrow cambial zone showing presence of fusiform and ray initials and less xylem differentiation i The continuous ring of vascular cambium and isolated lignified xylem groups in the BRZ treated plants. Note the inhibitory effect on the fibre secondary wall development and lignification. Scale bar = a,d, g = 50 µm; b,e,h = 20 µm; c,f,i = 25 µm

EBR induced enhancement of xylogenesis was evident from the increase in radial extent of xylem with increase in concentration of exogenously applied hormone (Fig. 1d, Table 2). The radial extent of xylem increased significantly between control and lower concentration (650 µm) of EBR while no significant variation between higher concentration like 1.5 ppm and 2 ppm (830 µm). Cambial zone cells actively divide and differentiate towards both xylem and phloem (Fig. 1e). Seedlings treated with 0.1 ppm EBR had xylem tissue with multiple vessels and thick walled fibers (Fig. 1f). Xylogenesis was enhanced following treatment with 0.5 ppm EBR. Fiber walls appeared more thicker in seedlings treated with 1 ppm EBR. Maximum radial extent of xylem was observed in plants treated with higher concentration (2 ppm) of EBR (Fg 1f).

Exogenous application of BRZ showed a pronounced affect on xylogensesis. Secondary xylem development was inhibited at 2 µM concentration (Fig. 1g), while at 5 µM treated plants showed a complete ring of 2–3 layered vascular cambium with no distinct lignified xylem elements (Fig. 1h). The xylem fibres near the cambial zone showed thin secondary walls indicating inhibition of secondary wall deposition by BRZ. Although, fully differentiated vessels were observed in the xylem, which is a diagnostic feature of secondary xylem, the fiber walls remain poorly lignified giving the appearance of incomplete ring of xylem. Similar pattern of xylem development was also observed in plants treated with 20 µM BRZ (Fig. 1i).

Effect of EBR and BRZ on Dimensional Changes in the Xylem Elements

Fiber length decreased in EBR treated plants in a dose dependent manner while fiber width did not show any significant variation (Table 1). The length and width of vessel elements increased significantly in EBR treated plants (Table 1). The maximum length and width of vessel elements was found in 2 ppm treated plants indicating elongation and expansion of vessel elements are related to higher concentration of EBR. Apparently, vessels appeared less in number in plants treated with EBR 0.1–1.5 ppm, however their frequency increased significantly in plants treated with 2 ppm EBR. Fiber wall thickness increased in EBR treated seedlings in a dose dependent manner. A significant increase in radial extent of xylem was observed in the plants treated with higher concentration of EBR indicating active xylogenesis.

The length of xylem fibres decreased significantly in BRZ treated plants in a dose dependent manner (Table 2). The length of vessel elements increased significantly from lower concentration to higher concentration of BRZ treated seedlings (Table 2). A significant difference in vessel element width was noted between treated (BRZ 50 µM and BRZ 1 µM) and control plants.

Effect of EBR and BRZ on Pattern and Distribution of Lignin

Epi-fluorescence microscopy revealed the autofluorescence of lignified walls of xylem elements and pericycle fibres in the cortex (Fig. 2a). The richness of guaiacyl lignin monomeric units in vessel walls was detected by the high intensity of fluorescence signals compared to that of fibres (Fig. 2b). The analysis of lignification pattern in control plants using Weisner reaction revealed more lignin concentration in vessel wall (Fig. 2c). The Mäule reaction showed the syringyl lignin rich fibre walls while guaiacyl units were predominent in vessel and parenchyma cell walls (Fig. 2d).

a–k Epi-fluorescence and bright field images from stem transverse sections of control (a-d), EBR treated (e–h) and BRZ treated (i-k) plants showing pattern of lignin distribution. c, g and j = Weisner reaction; d, h and k = Mäule reaction. a Autoflurescence of lignified elements in secondary xylem ring and arcs of pericyclic fibres distributed in cortex. b Enlarged view from ‘a’ showing relatively more autofluorescence from vessel wall (V) c Weisner reaction showing intense staining in the vessel and fibre cell walls d Secondary xylem following Mäule reaction showing distribution of syringyl units in the fibre secondary walls e Intense autofluorescence from the lignified secondary xylem cylinder f Enlarged view from ‘e’ showing fluorescence from vessel (V) and fibre walls g Weisner reaction showing intense lignification in the cell walls of fibres and vessels. Arrows indicate more lignin distribution in the cell corners h Mäule reaction showing incorporation of syringyl lignins in the walls of vessels (arrowheads, V) and fibres (arrows) i Relatively weak autoflurescence from xylem cylinder and pericyclic fibres j Weisner reaction showing inhomogenous lignin distribution pattern in the xylem elements k Mäule reaction showing weak staining from the thin cell wall of xylem elements Scale bar = a,e,i = 100 µm; b,f,c,d,g,h,j,k = 25 µm

Fluorescence microscopy and histochemical methods revealed the influence of exogenous EBR on lignification pattern in L. leucocephala. The intensity of fluorescence was relatively less in the xylem cylinder of 0.1 ppm EBR treated plants compared to that of control ones (Fig. 2e). Similar pattern of fluorescence, staining pattern for Weisner and Mäule reaction from vessels and fibres confirmed the presence of more syringyl lignins in their cell walls (Fig. 2f, g, h). This unusual pattern of lignin monomer distribution was also noticed in fibres and vessel walls of seedlings treated with higher concentrations of EBR.

The inhibitory effect of BRZ on xylogenesis was also reflected in the cell wall lignification pattern. Fluorescence microscopy showed scattered groups of lignified xylem elements separated by non-lignified cells (Fig. 2i). Vessel wall showed high fluorescence intensity indicating the presence of highly condensed lignin units (Fig. 2i). Weak staining intensity for Weisner reaction was evident from the stem of seedlings treated with 2 µM BRZ (Fig. 2j). Mäule reaction also showed the presence of more guaiacyl units in the vessel wall (Fig. 2h). However, there was no change in the heterogenous nature of lignin monomeric units between the walls of fibres and vessel elements. Although lignin monomeric composition did not show variation compared to other treatments, the fluorescence intensity decreased drastically from the xylem cylinder of plants treated with 5 µM BRZ. Exogenous application of higher concentration of BRZ lead to more inhibitory effect on xylogenesis. The secondary wall thickness and lignin deposition reduced significantly resulting in weak fluorescence signals from the elements of scattered xylem groups.

Ultra-Structural Changes and Lignification Pattern

The TEM analysis of ultrathin sections contrasted with KMnO4 revealed the ultrastructural changes in the cell wall and distribution pattern of lignin in plants treated with EBR and BRZ. The control plants showed fibres with lignin rich, electron dense regions in the compound middle lamellae, cell corners, S1 and S3 wall layers of secondary wall (Fig. 3a). An increase in the thickness of secondary wall was evident in the EBR treated plants (Fig. 3b). The lignin distribution was more in the compound middle lamellae (CML) region however, a uniform electron density pattern was observed throughout the secondary wall (Fig. 3b). The xylem fibres in the plants treated with BRZ showed relatively thin secondary wall, electron translucent regions in the cell corners (Fig. 3c, f), CML (Fig. 4c) and S1 layer of the secondary wall (Fig. 3d, e). These changes suggest the secondary wall thickness and lignin distribution have been altered in response to of BRZ treatment.

a–f TEM images from transverse sections of xylem tissue of control (a), EBR (b) and BRZ (c–f) treated plants of L. leucocephala. (KMnO4 contrasting). a Lignin distribution in the compound middle lamellae of a fiber. Note the secondary wall with more lignin distributed in the S1 and S3 wall layers. b Thick secondary walls of adjacent of fibers showing less electron density. Note the electron dense compound middle lamellae region. c Relatively thin secondary walls and electron translucent cell corner region (arrow) of fibres. d The electron translucent areas between S1 and S2 regions of secondary wall indicating poor lignin distribution e & f Inhomogenous lignin distribution between S1 and S2 layers (e, at arrows) and cell corner middle lamellae region (f, at arrows) of fibres. Scale bar- 1 µm

a–e Immunolocalization of low substituted xylans (Ls ACG Xs) in the control (a), EBR (b) and BRZ (c–e) treated plants. a The fiber walls showing dense labelling for Ls ACG Xs throughout the secondary wall. Note the weak labelling in compound middle lamellae region. b Fiber showing a strong Ls ACG Xs labelling in secondary walls and CML regions (c–e). Intense Ls ACG Xs labelling at radial (c) and tangential (d) region of fiber secondary walls. Note the weak labelling in the cell corner and compound middle lamellae regions (e). Scale bar = 1 µm

Immunolocalization of Xylans

The LM10 labelling revealed the distribution pattern of low substituted xylans (Ls ACG Xs) in xylem fibres. The control plants showed strong labelling throughout the secondary wall while less gold density was evident in the CML regions (Fig. 4a). The EBR treated plants showed an increase in gold particle distribution especially in the CML region (Fig. 4b). The BRZ treated plant also showed strong Ls ACG Xs labelling from tangential and radial secondary wall regions (Fig. 4c-e) while weak labelling was noticed in the CML region (Fig. 4d, e).

The highly substituted xylans (hs ACG Xs) labelled with LM 11 monoclonal antibodies revealed a strong labelling from the secondary wall region of xylem fibres from control plants (Fig. 5a). The density of gold was more evident in the bending region of secondary wall suggesting relatively more hs ACG Xs distribution in this region (Fig. 5a). The EBR treated plants showed strong hs ACG Xs labelling from secondary wall (Fig. 5b, c), CML and cell corners (Fig. 5d). The LM11 labelling of BRZ treated plants showed a decrease in the hs ACG Xs labelling in the secondary wall especially inner wall layers. The strong labelling was mainly confined to the S1 layer of fiber wall (Fig. 5e). The bending region of secondary wall also showed a weak labelling (Fig. 5f) suggesting BRZ treatment negatively influences the hs ACG Xs distribution in the cell wall of xylem fibres.

a–e Immunolocalization of highly substituted xylans (hs ACG Xs) in the control (a) and plants treated with EBR (b–d) and BRZ (e, f). a Intense labelling for hs ACG Xs from secondary wall of fibers. Note relatively more density of gold particles at the bending region of secondary wall. b–e Fiber walls showing hs ACG Xs labelling from secondary wall (b) and cell corner middle lamellae regions (c, d). e–f Weak labelling of hs ACG Xs from secondary wall regions of fibers. Note the strong labelling mainly confined to the S1-S2 transition zone. The bending region of the secondary wall and cell corners also show weak hs ACG Xs labelling (f). Scale bar = 1 µm

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that the exogenous application of 24-epibrassinolide (EBR) have a predominant effect on xylogenesis and anatomical structure of xylem elements of L. leucocephala. The application of low concentration of EBR enhances cell division in cambial zone, whereas, its higher concentration results in rapid cell differentiation resulting in more xylem formation. Earlier studies also indicate the role of EBR in cell division and differentiation process in cultured tuber explants of Jerusalem artichoke (Clause and Zurek 1991), onion root tip cells (Howel et al. 2007), tobacco BY-2 cell suspension culture (Miyazawa et al. 2003) and Arabidopsis (Cheon et al. 2010). Elevated brassinosteroid levels resulted in enhancement of secondary growth and tension wood formation while inhibition of BR synthesis resulted in decreased secondary vascular tissue differentiation in poplar (Du et al. 2020). Hence, enhancement of cambial cell division in EBR treated stem of L. leucocephala is in agreement with earlier reports on stimulatory effects of BR on cell division. The increase in radial extent of xylem following treatment indicates that BR enhances secondary xylem differentiation in L. leucocephala. In Zinnia system, BRs regulate the expression of several genes associated with xylem formation (Fukuda 1997). BRs have been identified in cambial scrapings of Pinus sylvestris (Kim et al. 1990). The coordinated function of BR and BRs and XET (Xyloglucan endotransglycosylase) in xylem formation reported to be evident from higher levels of BRV1 expression in paratracheary parenchyma cells surrounding vessel elements in soyabean epicotyls (Oh et al. 1998). The BR deficient Arabidopsis mutant (cpd) exhibits unequal division of the cambium, producing more phloem fibers at the expanse of xylem cells (Szekeres et al. 1996). BRs may be involved in deciding which differentiated cells (phloem or xylem cells) are formed from cambial cells (Nagata et al. 2001). Brassinazole has reported to be the only specific brassinosteroid biosynthesis inhibitor (Asami and Yoshida 1999). In the present study, the exogenous application of BRZ resulting in reduction in radial extent of xylem suggests its inhibitory effect on xylogenesis. Earlier studies also indicate the inhibitory role of brassinazole in the development of secondary xylem in L. sativam (Nagata et al. 2001) and in Cress plants (Nagata et al. 2001). The restoration of BRZ induced morphological changes by the application of brassinolide in Arabidopsis suggested that brassinazole exhibits its effect by reducing the supply of brassinolide in the plant (Asami et al. 2000).

Brassinosteroids are believed to be one of the well-known promoters of cell expansion. The EBR induced xylem in L. leucocephala showed relatively elongated and wider vessel elements indicating enhancement of cell expansion. Promotion of cell expansion through BR-regulated expression of genes involved in cell wall modifications, cellulose biosynthesis, ion and water transport and cytoskeleton rearrangements have been demonstrated in genetic studies and microarray analysis (Clouse and Sasse 1998; Kim and Wang 2010) and many of the genes in this classification have also been shown to be direct target of the BZR1 and BES1 transcription factors (Guo et al. 2009; Xie et al. 2011; Yu et al. 2011). The inhibition of brassinosteroid biosynthesis by exogenous application of brassinazole also indicates the important role played by brassinosteroid in cell elongation during xylogenesis. BRZ treatment resulted in decrease in the fiber length and width. The reduced length of vessel elements also suggests that elongation of xylem elements is affected in BRZ treated plants. The contradictory results on cell dimension in the seedlings of L. leucocephala treated with EBR and BRZ demonstrates the important role of brassinosteroids in the elongation growth of cells during xylogenesis.

The increase in fiber wall thickness and lignification is evident in the EBR induced secondary xylem of L. leucocephala. On the other hand, BRZ treatment resulted in reverse effect on secondary wall thickness and lignification in secondary xylem elements. The inhibitory effect of BRZ was more apparent in the secondary wall development and lignifcation of xylem fibre in L. leucocephala. The histochemical analysis suggests that the exogenously applied EBR reduces condensed lignin units and increased the syringyl lignin units. Fluorescence microscopy has also revealed the weak fluorescence signals from secondary wall suggesting the change in lignin monomeric composition rather than a inhibitory effect of lignin biosynthesis by EBR treatment. Previous studies also demonstrate that BRs are involved in regulation of lignin and cellulose biosynthesis during xylogenesis in plants (Sun et al. 2014; Jin et al. 2017; Gao et al. 2019).

The effect of epibrassinolide (EBR) on biosynthesis of cell wall components have been reported in Arabidopsis (Schrick et al. 2004; Xie et al. 2011), Liriodendron tulifera (Jin et al. 2017) and poplar (Gao et al. 2019). In the present study, the major changes observed after EBR and BRZ treatment was variation in the distribution pattern of syringyl lignin, low substituted and highly substituted xylans. The distribution of xylan and syringyl lignin was more in the secondary wall of EBR treated fibres while they have been decreased in the BRZ treated plants. In Liriodendron, the EBR was reported to affect expression of lignin biosynthesis genes and alter the hemicellulose composition (Jin et al. 2014). In poplar, exogenous application of EBR resulted in an increase of xylan, galactan and arabinan content (Gao et al. 2019). We also found a similar change in the distribution pattern of xylan and lignin in L. leucocephala. Xylan forms the major hemicellulose component in the secondary wall of hard wood elements. The variation in syringyl lignin distribution appears to be in correspondence with xylan suggesting a possible cross interaction between xylan and syringyl lignin monomers in the secondary cell wall. Plausibly, EBR may influence the monolignol ratio in cell wall by changing the hemicellulose composition. Our results are in agreement with Gao et al (2019) who proposed EBR regulates the cell wall integrity by altering hemicellulose and pectic network.

Conclusion

The present study demonstrates that the exogenous application of 24-epibrassinolide has a predominant effect in enhancing the important stages of xylogenesis such as cambial cell division, cell elongation, secondary wall thickness and deposition of xylan and syringyl monolignol units. The reverse effect in these developmental stages following exogenous application of EBR inhibitor, brassinazole also suggests the importance of brassinosteroid in xylem development and cell wall chemistry in L. leucocephala. The effect on secondary wall thickness and xylan-lignin chemistry warrant the significance of detailed studies to unravel the regulatory mechanism of BR in developing woodiness in trees.

References

Asami T, Yoshida S (1999) Brassinosteroid biosynthesis inhibitors. Trends Plant Sci 4:348–353

Asami T, Min YK, Nagata N, Yamagishi K, Takatsuto S, Fujioka S, Murofushi N, Yamaguchi I, Yoshida S (2000) Chareacterization of Brassinazole, a trizole type brassinosteroid inhibitor. Plant Physiol 123:93–99

Berlyn GP, Miksche JP (1976) Botanical Microtechnique and Cytochemistry. The Iowa State University Press, Ames, Iowa, p 326

Boudet AM, Lapierre C, Grima PJ (1995) Biochemistry and molecular biology of lignifications. New Phytol 129:203–236

Butto V, Deslauriers RS, Rozenberg P, Shishov V, Morin H (2020) The role of plant hormones in tree ring formation. Trees 34:315–335

Camargo ELO, Ployet R, Cassan-Wang H, Mounet F, Grima-Pettenati J (2018) Digging in wood: New insights in the regulation of wood formation in tree species. Adv Botan Res 89:201–233

Cheon J, Park SY, Schulz B, Choe S (2010) Arabidopsis brassinosteroid biosynthetic mutant dwarf7-1 exhibits slower rates of cell division and shoot induction. BMC Plant Biol 10:270

Clause SD, Zurek D (1991) Molecular analysis of brassinolide action in plant growth and development. In: Cutler HG, Yokota T, Adamm G (eds) Brassinosteroids: Chemistry, Bioactivity, and Applications. ACS. Symp. Series 474. Amer Chem Soc., Washington, DC pp 122–140

Clouse SD, Sasse JM (1998) Brassinosteroids: Essential regulators of plant growth and development. Ann Rev Plant Phys Plant Mol Biol 49:427–451

Dengler NG (2001) Regulation of vascular development. J Plant Growth Regul 20:1–13

Divi U, Krishna P (2009) Brassinosteroid: a biotechnological target for enhancing crop yield and stress tolerance. New Biotechnol 26:131–136

Donaldson L (1992) Lignin distribution during late wood formation in Pinus radiata D.DON. IAWA Bull 13:381–387

Du J, Gerttula S, Li Z, Zhao S-T, Liu Y-L, Lu M-Z, Groover AT (2020) Brassinosteroid regulation of wood formation in poplar. New Phytol 225:1516–1530

Fedina E, Yarin A, Mukhitova F, Blufard A, Chechetkin I (2017) Brassinosteroid induced changes of lipid composition in leaves of Pisum sativum L. during senescence. Steroids 117:25–28

Fukuda H (1997) Tracheary element differentiation. Plant Cell 9:1147–1156

Gao J, Yu M, Zhu S, Zhou L, Liu S (2019) Effects of exogenous 24- epibrassinolide and brassinazole on negative gravitropism and tension wood formation in hybrid poplar (Populus deltoids 9 Populus nigra). Planta 249:1449–1463

Guo H, Li L, Yu X, Algreen A, Yin Y (2009) Three related receptor-like kinases are required for optimal cell elongation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:7648–7653

Howell WM, Keller GE, Kirkpatrick JD, Jenkins RL, Hunsinger RN, McLaughlin EW (2007) Effects of the plant steroidal hormone, 24-epibrassinolide, on the mitotic index and growth of onion (Allium cepa) root tips. Genet Mol Res 6:50–58

Hyunjung J, Jihye D, Soo-Jeong S, Joon Weon C, Young Im C, Wook K, Mi K (2014) Exogenously applied 24-epi brassinolide reduces lignification and alters cell wall carbohydrate biosynthesis in the secondary xylem of Liriodendron tulipifera. Phytochemistry 101:40–51

Immanen J, Nieminen K, Smolander O-P, Kojima M, Alonso Serra J, Koskinen P, Zhang J, Elo A, Mahonen AP, Street N, Bhalerao RP, Auvinen P, Sakakibara H, Helariutta Y (2016) Cytokinin and auxin display distinct but interconnected distribution and signaling profiles to stimulate cambial activity. Curr Biol 26:1990–1997

Jin H, Do J, Shin SJ, Choi JW, Choi YI, Kim W, Kwon M (2014) Exogenously applied 24-epi brassinolide reduces lignification and alters cell wall carbohydrate biosynthesis in the secondary xylem of Liriodendron tulipifera. Phytochemistry 101:40–51

Jin YL, Tang RJ, Wang HH, Jiang CM, Bao Y, Yang Y, Liang MX, Kong F, Li B, Zhang HX (2017) Overexpression of Populus trichocarpa CYP85A3 promotes growth and biomass production in transgenic trees. Plant Biotechnol J 15:1309–1321

Kim SK, Abe H, Little CHA, Pharis RP (1990) Identification of two brassinosteroids from the cambial region of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, after detection using a dwarf rice lamina inclination bioassay. Plant Physiol 94:1709–1713

Kim TW, Wang ZY (2010) Brassinosteroid Signal Transduction Factors. Annu Rev Plant Biol 61:681–704

Larson PR (1994) The Vascular cambium. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany

Liu Z-H, Chen Y, Wang N-N, Chen Y-H, Wei N, Lu R, Li Y, Li X-B (2019) A basic helix loop helix protein promotes fibre elongation of cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) by modulating brassinosteroid biosynthesis and signalling. New Phytol 225:2439–2452

Mehistsuka G, Nakano J (1979) Studies on the mechanism of lignin color reaction (XIII): Mäule color reaction (9). Mokuzai Gakkaishi 25:588–594

Minami A, Takahashi K, Inoue SI, Tada Y, Kinoshita T (2019) Brassinosteroid induces phosphorylation of the plasma membrane H+-ATPase during hypocotyl elongation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol 60:935–944

Miyazawa Y, Nakajima N, Abe T, Sakai A, Fujioka S, Kawano S, Kuroiwa T, Yoshida S (2003) Activation of cell proliferation by brassinolide application in tobacco BY-2 cells: effects of brassinolide on cell multiplication, cell-cycle-related gene expression, and organellar DNA contents. J Exp Bot 54:2669–2678

Nagata N, Asami T, Yoshida S (2001) Brassinozole, an inhibitor of brassinosteroid biosynthesis, inhibits development of secondary xylem in cress plants (Lepidiun sativum). Plant Cell Physiol 42:1006–1011

Noh SA, Choi YI, Cho JS, Lee H (2015) The poplar basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor BEE3 - Like gene affects biomass production by enhancing proliferation of xylem cells in poplar. Biochem Biophys Res Comm 462:64–70

Nolan TM, Vukasinovic N, Liu D, Russinova E, Yin Y (2020) Brassinosteroids: Multidimensional regulators of plant growth, development and stress response. Plant Cell 32:295–318

Oh MH, Romanow WG, Smith RC, Zamski E, Sasse J, Clouse SD (1998) Soyabean BRU1encodes a functional xyloglucan endotransglycosylase that is highly expressed in inner epicotyls tissues during brassinosteroid-promoted elongation. Plant Cell Physiol 39:124–130

Pramod S, Rajput KS, Rao KS (2019) Immnolocalization of β (1–4) galactan, xyloglucan ad xylan in the reaction xylem of Leucaena leucocephala (Lam) de Wit. Plant Physiol Biochem 142:217–223

Retzer K, Akhmanova M, Konstantinova N, Malinska K, Leitner J, Petrasek J, Luschnig C (2019) Brassinosteroid signalling delimits root gravitropism via sorting of the Arabidopsis PIN2 auxin transporter. Nat Commun 10:5516

Schrick K, Fujioka S, Takatsuto S, Stierhof YD, Stransky H, Yoshida S, Jürgens G (2004) A link between sterol biosynthesis, the cell wall, and cellulose in Arabidopsis. Plant J 38:227–243

Sharma A, Zheng B (2019) Molecular responses during plant grafting and its regulation by auxins, cytokinins and gibberellins. Biomolecules 9:397

Song LI, Zhou XY, Li LI, Xue LJ, Yang XI, Xue HW (2009) Genome-wide analysis revealed the complex regulatory network of brassinosteroid effects in photomorphogenesis. Molecular Plant 2:755–772

Steber CM, Mccourt P (2001) A role for brassinosteroids in germination in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 125:763–769

Sun Y,Veerabomma S, Mohammed F, Noureddine, A, Eric H, Paxton P, Allen RD (2014) Brassinosteroid signaling affects secondary cell wall deposition in cotton fibers. Ind Crop Prod 1–9

Szekeres M, Németh K, Koncz-Kálmán Z, Mathur J, Kauschmann A, Altmann T, Rédei GP, Nagy F, Schell J, Koncz C (1996) Brassinosteroids rescue the deficiency of CYP90, a cytochrome P450, controlling cell elongation and de-etiolation in Arabidopsis. Cell 85:171–182

Tae-Wuk K, Marta M, Bergmann DC, Zhi-Yong W (2012) Brassinosteroid regulates stomatal development by GSK3-mediated inhibition of a MAPK pathway. Nature 482:419–422

Tian H, Bingsheng LV, Ding T, Bai M, Ding Z (2018) Auxin-BR interaction regulates plant growth and development. Front Plant Sc 8:2256

Vallet C, Chabbert B, Czaninski Y, Monties B (1996) Histochemistry of lignin deposition during sclerenchyma differentiation in alfalfa stems. Ann Bot 78:625–632

Wada K, Marumo S, Abe H, Morishita T, Nakamura K, Uchiyama M, Mori K (1984) A rice lamina inclination test-a micro-quantitative bioassay for brassinosteroids. Agric Biol Chem 48:719–726

Xie L, Yang C, Wang X (2011) Brassinosteroids can regulate cellulose biosynthesis by controlling the expression of CESA genes in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot 62:4495–4506

Yamamoto R, Demura T, Fukuda H (1997) Brassinosteroids induce entry into the final stage of tracheary element differentiation in cultured Zinnia cells. Plant Cell Physiol 38:980–983

Yu X, Li L, Zola J, Aluru M, Ye H, Foudree A, Guo H, Anderson S, Aluru S, Liu P, Rodermel S, Yin Y (2011) A brassinosteroid transcriptional network revealed by genome-wide identification of BESI target genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 65:634–646

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to Central University of Kerala for providing financial assistance under Department Research Assistance. The first author is thankful to University Grants Commission, New Delhi for financial assistance under DSKPDF scheme. Authors are grateful to Sophisticated Instrumentaion Facility, AIIMS, New Delhi for the TEM analysis of samples.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Pramod designed and conducted the TEM experiments, interpreted the results and prepared the manuscript. Anju and Rajesh conducted the lab experiments and involved in manuscript data preparation. Thulaseedharan and K S Rao supervised the work and critically evaluated the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Handling Editor: Pramod Kumar Nagar.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pramod, S., Anju, M., Rajesh, H. et al. Effect of Exogenously Applied 24-Epibrassinolide and Brassinazole on Xylogenesis and Microdistribution of Cell Wall Polymers in Leucaena leucocephala (Lam) De Wit. J Plant Growth Regul 41, 404–416 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00344-021-10313-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00344-021-10313-6