Abstract

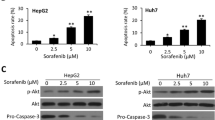

Sorafenib (Nexavar®) is currently the only FDA-approved small molecule targeted therapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. The use of structural analogues and derivatives of sorafenib has enabled the elucidation of critical targets and mechanism(s) of cell death for human cancer lines. We previously performed a structure–activity relationship study on a series of sorafenib analogues designed to investigate the inhibition overlap between the major targets of sorafenib Raf-1 kinase and VEGFR-2, and an enzyme shown to be a potent off-target of sorafenib, soluble epoxide hydrolase. In the current work, we present the biological data on our lead sorafenib analogue, t-CUPM, demonstrating that this analogue retains cytotoxicity similar to sorafenib in various human cancer cell lines and strongly inhibits growth in the NCI-60 cell line panel. Co-treatment with the pan-caspase inhibitor, Z-VAD-FMK, failed to rescue the cell viability responses of both sorafenib and t-CUPM, and immunofluorescence microscopy shows similar mitochondrial depolarization and apoptosis-inducing factor release for both compounds. These data suggest that both compounds induce a similar mechanism of caspase-independent apoptosis in hepatoma cells. In addition, t-CUPM displays anti-proliferative effects comparable to sorafenib as seen by a halt in G0/G1 in cell cycle progression. The structural difference between sorafenib and t-CUPM significantly reduces inhibitory spectrum of kinases by this analogue, and pharmacokinetic characterization demonstrates a 20-fold better oral bioavailability of t-CUPM than sorafenib in mice. Thus, t-CUPM may have the potential to reduce the adverse events observed from the multikinase inhibitory properties and the large dosing regimens of sorafenib.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- HCC:

-

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- t-CUPM:

-

trans-4-{4-[3-(4-Chloro-3-trifluoromethyl-phenyl)-ureido]-cyclohexyloxy-pyridine-2-carboxylic acid methylamide

References

Sherman M (2010) Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncology 78(Suppl 1):7–10

Jemal A et al (2009) Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin 59(4):225–249

Zhang T et al (2010) Sorafenib improves the survival of patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Anticancer Drugs 21(3):326–332

Furuse J (2008) Sorafenib for the treatment of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Biologics 2(4):779–788

Lowinger TB et al (2002) Design and discovery of small molecules targeting raf-1 kinase. Curr Pharm Des 8(25):2269–2278

Liu H et al (2010) Enhanced selectivity profile of pyrazole-urea based DFG-out p38alpha inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 20(16):4885–4891

Wilhelm SM et al (2004) BAY 43-9006 exhibits broad spectrum oral antitumor activity and targets the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway and receptor tyrosine kinases involved in tumor progression and angiogenesis. Cancer Res 64(19):7099–7109

Wilhelm S et al (2006) Discovery and development of sorafenib: a multikinase inhibitor for treating cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov 5(10):835–844

Wood LS (2009) Management of vascular endothelial growth factor and multikinase inhibitor side effects. Clin J Oncol Nurs 13(Suppl):13–18

Strumberg D et al (2002) Results of phase I pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies of the Raf kinase inhibitor BAY 43-9006 in patients with solid tumors. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 40(12):580–581

Liu JY et al (2009) Sorafenib has soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibitory activity, which contributes to its effect profile in vivo. Mol Cancer Ther 8(8):2193–2203

Schmelzer KR et al (2005) Soluble epoxide hydrolase is a therapeutic target for acute inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102(28):9772–9777

Chiamvimonvat N et al (2007) The soluble epoxide hydrolase as a pharmaceutical target for hypertension. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 50(3):225–237

Inceoglu B et al (2008) Soluble epoxide hydrolase and epoxyeicosatrienoic acids modulate two distinct analgesic pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105(48):18901–18906

van Erp NP, Gelderblom H, Guchelaar HJ (2009) Clinical pharmacokinetics of tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Cancer Treat Rev 35(8):692–706

Webler AC et al (2008) Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids are part of the VEGF-activated signaling cascade leading to angiogenesis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 295(5):C1292–C1301

Zhang G et al (2013) Epoxy metabolites of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) inhibit angiogenesis, tumor growth, and metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110(16):6530–6535

Hwang SH et al (2013) Synthesis and biological evaluation of sorafenib- and regorafenib-like sEH Inhibitors. BMCL 23(13):3732–3737

Hwang SH et al (2007) Orally bioavailable potent soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibitors. J Med Chem 50(16):3825–3840

Inoue H et al (2011) Sorafenib attenuates p21 in kidney cancer cells and augments cell death in combination with DNA-damaging chemotherapy. Cancer Biol Ther 12(9):827–836

Rose TE et al (2010) 1-Aryl-3-(1-acylpiperidin-4-yl)urea inhibitors of human and murine soluble epoxide hydrolase: structure–activity relationships, pharmacokinetics, and reduction of inflammatory pain. J Med Chem 53(19):7067–7075

Jester BW et al (2010) A coiled-coil enabled split-luciferase three-hybrid system: applied toward profiling inhibitors of protein kinases. J Am Chem Soc 132(33):11727–11735

Sulkes A (2010) Novel multitargeted anticancer oral therapies: sunitinib and sorafenib as a paradigm. Isr Med Assoc J 12(10):628–632

Worns MA et al (2010) Sunitinib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma after progression under sorafenib treatment. Oncology 79(1–2):85–92

Holbeck SL, Collins JM, Doroshow JH (2010) Analysis of Food and Drug Administration-approved anticancer agents in the NCI60 panel of human tumor cell lines. Mol Cancer Ther 9(5):1451–1460

Harimoto N et al (2010) The significance of fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 expression in differentiation of hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncology 78(5–6):361–368

Chen G et al (2010) EphA1 receptor silencing by small interfering RNA has antiangiogenic and antitumor efficacy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Rep 23(2):563–570

Tannapfel A et al (2003) Mutations of the BRAF gene in cholangiocarcinoma but not in hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut 52(5):706–712

Liu L et al (2006) Sorafenib blocks the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway, inhibits tumor angiogenesis, and induces tumor cell apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma model PLC/PRF/5. Cancer Res 66(24):11851–11858

Tai WT et al (2011) Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 is a major kinase-independent target of sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 55(5):1041–1048

Huang R et al (2010) The multikinase inhibitor sorafenib induces caspase-dependent apoptosis in PC-3 prostate cancer cells. Asian J Androl 12(4):527–534

Fecteau JF et al (2011) Sorafenib-induced apoptosis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells is associated with downregulation of RAF and Mcl-1. Mol Med 18(1):19–28

Panka DJ et al (2006) The Raf inhibitor BAY 43-9006 (sorafenib) induces caspase-independent apoptosis in melanoma cells. Cancer Res 66(3):1611–1619

Katz SI et al (2009) Sorafenib inhibits ERK1/2 and MCL-1(L) phosphorylation levels resulting in caspase-independent cell death in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Cancer Biol Ther 8(24):2406–2416

Joza N et al (2001) Essential role of the mitochondrial apoptosis-inducing factor in programmed cell death. Nature 410(6828):549–554

Norberg E, Orrenius S, Zhivotovsky B (2010) Mitochondrial regulation of cell death: processing of apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF). Biochem Biophys Res Commun 396(1):95–100

Jain L et al (2010) Hypertension and hand-foot skin reactions related to VEGFR2 genotype and improved clinical outcome following bevacizumab and sorafenib. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 29:95

Liu Y-O et al (2011) Preparation of sorafenib selfmicroemulsifying drug delivery system and its relative bioavailability in rats. J Chin Pharm Sci 20:164–170

Wang XQ et al (2011) Bioavailability and pharmacokinetics of sorafenib suspension, nanoparticles and nanomatrix for oral administration to rat. Int J Pharm 419(1–2):339–346

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Michael Praddy of the MCB Imaging Facility for help with collecting and analyzing our immunohistochemical data on the Olympus FV100 laser point scanning microscope. Special thanks to Carol Oxford and the UCD Flow Cytometry Shared Resource facility for help with collecting and analyzing cell cycle data. This work was supported in part by NIEHS Grant ES02710, NIEHS Superfund Grant P42 ES04699, and NIHLB Grant HL059699 (all to B.D.H.). This work was also supported by NIH Grants 5UO1CA86402 (Early Detection Research Network), 1R01CA135401-01A1, and 1R01DK082690-01A1 (all to R.H.W.), and the Medical Service of the US Department of Veterans’ Affairs (R.H.W.). A.T.W. was support by Award No. T32CA108459 from the National Institutes of Health. B.D.H. is a George and Judy Marcus senior fellow of the American Asthma Foundation.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wecksler, A.T., Hwang, S.H., Liu, JY. et al. Biological evaluation of a novel sorafenib analogue, t-CUPM. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 75, 161–171 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00280-014-2626-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00280-014-2626-2