Abstract

Purpose: FAU (1-(2′-deoxy-2′-fluoro-β-D-arabinofuranosyl) uracil) can be phosphorylated by thymidine kinase, methylated by thymidylate synthase, followed by DNA incorporation and thus functions as a DNA synthesis inhibitor. This first-in-human study of [F-18]FAU was conducted in cancer patients to determine its suitability for imaging and also to understand its pharmacokinetics as a potential antineoplastic agent. Methods: Six patients with colorectal (n=3) or breast cancer (n=3) were imaged with [F-18]FAU. Serial blood and urine samples were analyzed using HPLC to determine the clearance and metabolites. Results: Imaging showed that [F-18]FAU was concentrated in breast tumors and a lymph node metastasis (tumor-to-normal-breast-tissue-ratio 3.7–4.7). FAU retention in breast tumors was significantly higher than in normal breast tissues at 60 min and retained in tumor over 2.5 h post-injection. FAU was not retained above background in colorectal tumors. Increased activity was seen in the kidney and urinary bladder due to excretion. Decreased activity was seen in the bone marrow with a mean SUV 0.6. Over 95% of activity in the blood and urine was present as intact [F-18]FAU at the end of the study. Conclusions: Increased [F-18]FAU retention was shown in the breast tumors but not in colorectal tumors. The increased retention of FAU in the breast compared to bone marrow indicates that FAU may be useful as an unlabeled antineoplastic agent. The low retention in the marrow indicates that unlabeled FAU might lead to little marrow toxicity; however, the images were not of high contrast to consider FAU for diagnostic clinical imaging.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Aboagye EO, Price PM, Jones T (2001) In vivo pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in drug development using positron-emission tomography. Drug Discov Today 6(6):293–302

Fischman AJ, Alpert NM, Babich JW, Rubin RH (1997) The role of positron emission tomography in pharmacokinetic analysis. Drug Metab Rev 29(4):923–956

Gupta N, Price PM, Aboagye EO (2002) PET for in vivo pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic measurements. Eur J Cancer 38(16):2094–2107

Saleem A, Harte RJ, Matthews JC et al (2001) Pharmacokinetic evaluation of N-[2-(dimethylamino)ethyl]acridine-4-carboxamide in patients by positron emission tomography. J Clin Oncol 19(5):1421–1429

Aboagye EO, Saleem A, Cunningham VJ, Osman S, Price PM (2001) Extraction of 5-fluorouracil by tumor and liver: a noninvasive positron emission tomography study of patients with gastrointestinal cancer. Cancer Res 61(13):4937–4941

Brady F, Luthra SK, Brown GD et al (2001) Radiolabelled tracers and anticancer drugs for assessment of therapeutic efficacy using PET. Curr Pharm Des 7(18):1863–1892

Kissel J, Brix G, Bellemann ME et al (1997) Pharmacokinetic analysis of 5-[18F]fluorouracil tissue concentrations measured with positron emission tomography in patients with liver metastases from colorectal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res 57(16):3415–3423

McGuire AH, Dehdashti F, Siegel BA et al (1991) Positron tomographic assessment of 16 alpha-[18F] fluoro-17 beta-estradiol uptake in metastatic breast carcinoma. J Nucl Med 32(8):1526–1531

Saleem A, Yap J, Osman S et al (2000) Modulation of fluorouracil tissue pharmacokinetics by eniluracil: in-vivo imaging of drug action. Lancet 355(9221):2125–2131

Collins JM, Klecker RW, Katki AG (1999) Suicide prodrugs activated by thymidylate synthase: rationale for treatment and noninvasive imaging of tumors with deoxyuridine analogues. Clin Cancer Res 5(8):1976–1981

Danenberg PV, Malli H, Swenson S (1999) Thymidylate synthase inhibitors. Semin Oncol 26(6):621–631

Backus HH, Van Groeningen CJ, Vos W et al (2002) Differential expression of cell cycle and apoptosis related proteins in colorectal mucosa, primary colon tumours, and liver metastases. J Clin Pathol 55(3):206–211

Derenzini M, Montanaro L, Chilla A et al (2002) Evaluation of thymidylate synthase protein expression by Western blotting and immunohistochemistry on human colon carcinoma xenografts in nude mice. J Histochem Cytochem 50(12):1633–1640

Derenzini M, Montanaro L, Trere D et al (2002) Thymidylate synthase protein expression and activity are related to the cell proliferation rate in human cancer cell lines. Mol Pathol 55(5):310–314

Kawasaki G, Yoshitomi I, Yanamoto S, Mizuno A (2002) Thymidylate synthase and dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase expression in oral squamous cell carcinoma: an immunohistochemical and clinicopathologic study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 94(6):717–723

Nomura T, Nakagawa M, Fujita Y, Hanada T, Mimata H, Nomura Y (2002) Clinical significance of thymidylate synthase expression in bladder cancer. Int J Urol 9(7):368–376

Yamaoka H, Tsukuda M, Mochimatsu I et al (1998) Thymidylate synthase expression in patients with hypopharyngeal carcinoma. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho 25(7):1007–1012

Sun H, Collins JM, Mangner TJ, Muzik O, Shields AF (2003) Imaging [(18)F]FAU [1-(2′-deoxy-2′-fluoro-beta-D-arabinofuranosyl) uracil] in dogs. Nucl Med Biol 30(1):25–30

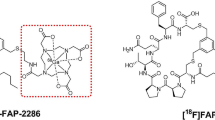

Mangner T, Klecker R, Anderson L, Shields A (2003) Synthesis of 2′-[18F]fluoro-2′-deoxy-ß-D-arabinofuranosyl nucleotides, [18F]FAU, [18F]FMAU, [18F]FBAU and [18F]FIAU, as potential pet agents for imaging cellular proliferation. Nucl Med Biol (30):215–224

Eiseman JL, Brown-Proctor C, Kinahan PE et al (2004) Distribution of 1-(2-deoxy-2-fluoro-beta-D-arabinofuranosyl) uracil in mice bearing colorectal cancer xenografts: rationale for therapeutic use and as a positron emission tomography probe for thymidylate synthase. Clin Cancer Res 10(19):6669–6676

Ebuchi M, Sakamoto S, Kudo H, Nagase J, Endo M (1995) Clinicopathological stages and pyrimidine nucleotide synthesis in human mammary carcinomas. Anticancer Res 15(4):1481–1484

Sakamoto S, Ebuchi M, Iwama T (1993) Relative activities of thymidylate synthetase and thymidine kinase in human mammary tumours. Anticancer Res 13(1):205–207

Wang H, Oliver P, Nan L et al (2002) Radiolabeled 2′-fluorodeoxyuracil-beta-D-arabinofuranoside (FAU) and 2′-fluoro-5-methyldeoxyuracil-beta-D-arabinofuranoside (FMAU) as tumor-imaging agents in mice. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 49(5):419–424

Copur MS, Chu E (2001) Thymidylate Synthase Pharmacogenetics in Colorectal Cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer 1(3):179–180

Copur S, Aiba K, Drake JC, Allegra CJ, Chu E (1995) Thymidylate synthase gene amplification in human colon cancer cell lines resistant to 5-fluorouracil. Biochem Pharmacol 49(10):1419–1426

Iqbal S, Lenz HJ (2001) Determinants of prognosis and response to therapy in colorectal cancer. Curr Oncol Rep 3(2):102–108

Salonga D, Danenberg KD, Johnson M et al (2000) Colorectal tumors responding to 5-fluorouracil have low gene expression levels of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase, thymidylate synthase, and thymidine phosphorylase. Clin Cancer Res 6(4):1322–1327

Wang W, Marsh S, Cassidy J, McLeod HL (2001) Pharmacogenomic dissection of resistance to thymidylate synthase inhibitors. Cancer Res 61(14):5505–5510

Yeh KH, Shun CT, Chen CL et al (1998) High expression of thymidylate synthase is associated with the drug resistance of gastric carcinoma to high dose 5-fluorouracil-based systemic chemotherapy. Cancer 82(9):1626–1631

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by funding from the National Cancer Institute grants CA 39566 and CA 82645.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, H., Collins, J.M., Mangner, T.J. et al. Imaging the pharmacokinetics of [F-18]FAU in patients with tumors: PET studies. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 57, 343–348 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00280-005-0037-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00280-005-0037-0