Abstract

Background

The World Health Organisation Surgical Safety Checklist (SSC) is a mandated part of surgical practice. Adherence to the SSC has been shown to result in improved patient outcomes. The aim of this study was to determine the current adherence to the timeout section of the SSC and, in particular, the function of individual team members.

Methods

A prospective pre- and post-intervention observational audit was conducted on the timeout section. The intervention involved an in-hospital display of interim results and distribution to theatre staff. Data were collected on participants, duration and compliance with checklist items for 400 theatre cases. There were 200 cases before and after the intervention.

Results

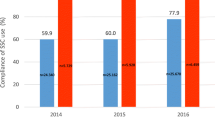

There were no cases in which the timeout section was completed correctly in its entirety. Post-intervention, there was a significant improvement in participation of theatre staff (excluding surgeons) as well as a significant improvement in items discussed and documented. Discussion of items such as anticipated critical events, pressure areas and the team introduction remained low. Some items on the checklist were discussed significantly more when a particular staff member participated.

Conclusion

Observed completion rates of the timeout section of the SSC were poor. Individual team members positively influenced checklist items more aligned to their role, highlighting the importance of timeout being performed by the entire theatre team. Improved performance was seen following audit and feedback.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Weiser TG, Regenbogen SE, Thompson KD et al (2008) An estimation of the global volume of surgery: a modelling strategy based on available data. Lancet 372:139–144

Organisation WH [Internet]. Safe surgery saves lives frequently asked questions 2014 (updated 2014 September). http://www.who.int/patientsafety/safesurgery/faq_introduction/en/. Accessed 9 Nov 2019

Gawande AA, Thomas EJ, Zinner MJ et al (1999) The incidence and nature of surgical adverse events in Colorado and Utah in 1992. Surgery 126:66–75

Kable AK, Gibberd RW, Spigelman AD (2002) Adverse events in surgical patients in Australia. Int J Qual Health Care 14:269–276

Fudickar A, Horle K, Wiltfang J et al (2012) The effect of the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist on complication rate and communication. Dtsch Arztebl Int 109:695–701

Haynes AB, Weiser TG, Berry WR et al (2009) A Surgical Safety Checklist to reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. N Engl J Med 360:491–499

Haugen AS, Sevdalis N, Softeland E (2019) Impact of the World Health Organization Surgical Safety Checklist on patient safety. Anesthesiology 131:420–425

Mazzocco K, Petitti DB, Fong KT et al (2009) Surgical team behaviors and patient outcomes. Am J Surg 197:678–685

Nugent E, Hseino H, Ryan K et al (2013) The Surgical Safety Checklist survey: a national perspective on patient safety. Ir J Med Sci 182:171–176

Helmio P, Blomgren K, Takala A et al (2011) Towards better patient safety: WHO Surgical Safety Checklist in otorhinolaryngology. Clin Otolaryngol 36:242–247

Russ SJ, Sevdalis N, Moorthy K et al (2015) A qualitative evaluation of the barriers and facilitators toward implementation of the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist across hospitals in England: lessons from the “Surgical Checklist Implementation Project”. Ann Surg 261:81–91

Haugen AS, Waehle HV, Almeland SK et al (2019) Causal analysis of World Health Organization’s Surgical Safety Checklist implementation quality and impact on care processes and patient outcomes: secondary analysis from a large stepped wedge cluster randomized controlled trial in Norway. Ann Surg 269:283–290

Weiser TG, Haynes AB, Dziekan G et al (2010) Effect of a 19-item Surgical Safety Checklist during urgent operations in a global patient population. Ann Surg 251:976–980

Giles K, Munn Z, Aromataris E et al (2017) Use of Surgical Safety Checklists in Australian operating theatres: an observational study. ANZ J Surg 87:971–975

de Jager E, Gunnarsson R, Ho Y-H (2018) Implementation of the World Health Organization Surgical Safety Checklist correlates with reduced surgical mortality and length of hospital admission in a high-income country. World J Surg 43:117–124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-018-4703-x

Gillespie BM, Marshall AP, Gardiner T et al (2016) Impact of workflow on the use of the Surgical Safety Checklist: a qualitative study. ANZ J Surg 86:864–867

Borchard A, Schwappach DL, Barbir A et al (2012) A systematic review of the effectiveness, compliance, and critical factors for implementation of safety checklists in surgery. Ann Surg 256:925–933

Clark SC. Cardiac Surgical Safety Checklist [Internet]. London: Society for Cardiothoracic Surgery in Great Britain & Ireland 2009 [updated 2009 December 12]. https://scts.org/cardiac-surgical-safety-checklist/. Accessed 9 Nov 2019

Ziman R, Espin S, Grant RE et al (2018) Looking beyond the checklist: an ethnography of interprofessional operating room safety cultures. J Interprof Care 32:575–583

Urbach DR, Govindarajan A, Saskin R et al (2014) Introduction of Surgical Safety Checklists in Ontario, Canada. N Engl J Med 370:1029–1038

Conley DM, Singer SJ, Edmondson L et al (2011) Effective Surgical Safety Checklist implementation. J Am Coll Surg 212:873–879

Gillespie BM, Harbeck EL, Lavin J et al (2018) Evaluation of a patient safety programme on Surgical Safety Checklist Compliance: a prospective longitudinal study. BMJ Open Qual 7:e000362

Helmio P, Takala A, Aaltonen LM et al (2012) WHO Surgical Safety Checklist in otorhinolaryngology-head and neck surgery: specialty-related aspects of check items. Acta Otolaryngol 132:1334–1341

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

This study was ethically approved by the local research governance committee.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Taplin, C., Romano, L., Tacey, M. et al. Everyone has Their Role to Play During the World Health Organisation Surgical Safety Checklist in Australia: A Prospective Observational Study. World J Surg 44, 1755–1761 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-020-05397-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-020-05397-2