Abstract

Introduction

Although population screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) has/had a significant impact on disease-specific mortality, coexisting systemic atherosclerosis represents the major impediment to improved longevity. We examined the feasibility and yield of full cardiovascular assessment concomitant with screening for AAA detection.

Methods

A total of 1032 asymptomatic men over the age of 50 years (328 were >60 years) underwent a detailed cardiac health questionnaire, sphygmomanometry, body mass index calculation, fasting lipid profiling, ultrasonographic (US) examination of their infrarenal aorta and carotid arteries, and treadmill exercise stress testing. Framingham and SCORE project estimations of the 10-year risk of ischemic heart disease (IHD) and fatal cardiovascular disease (CVD) of any cause were calculated for the men with an AAA and in those >60 years but with neither AAA nor known cardiac disease.

Results

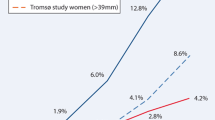

Overall, we detected an AAA >3 cm in 30 men (2.9%). Unaddressed obesity, smoking, hypertension, impaired glucose metabolism, and hypercholesterolemia were commonly identified in individuals both with and without an AAA, being notably frequent in those >60 years without an AAA. The 10-year risk of IHD and CHD in those >60 years was similar regardless of whether an AAA was present. Doppler screening for significant carotid stenosis had detection rates similar to those for aortic US scanning, being most useful in those >65 years of age. Exercise stress testing, however, was of only limited value when used nonselectively.

Conclusions

Modifiable atherosclerotic disease and cardiovascular risk can be readily detected in individuals presenting for AAA screening and are present to a significant degree at an earlier age. Consideration of selected, additional investigations is required to maximize the value of generalized screening programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

The Multicentre Aneurysm Screening Study Group. The Multicentre Aneurysm Screening Study (MASS) into the effect of abdominal aortic aneurysm screening on mortality in men: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2002;360:1531–1539

Muticentre Aneurysm Screening Study Group. Multicentre Aneurysm Screening Study (MASS): cost effectiveness analysis of screening for abdominal aortic aneurysms based on four year results from randomised control trial. BMJ 2002;325:1135

Newman AB, Arnold AM, Burke GL, et al. Cardiovascular disease and mortality in older adults with small abdominal aortic aneurysms detected by ultrasonography: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Intern Med 2001;134:182–190

Galland RB, Whiteley MS, Magee TR. The fate of patients undergoing surveillance of small abdominal aortic aneurysms. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 1998;16:104–109

The United Kingdom Small Aneurysm Trial Participants. Long-term outcomes of immediate repair compared with surveillance of small abdominal aortic aneurysms. N Engl J Med 2002;346:1445–1452

Lederle FA, Wilson SE, Johnson GR, et al. Immediate repair compared with surveillance of small abdominal aortic aneurysms. N Engl J Med 2002;346:1437–1444

Batt M, Staccini O, Pittaluga P, et al. Late survival after abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Eur J Endovasc Surg 1999;21:338–342

Norman PE, Jamrozik K, Lawrence-Brown MM, et al. Population based randomised controlled trial on impact of screening on mortality from abdominal aortic aneurysm. BMJ 2004;329:1259

Rodin MB, Daviglus ML, Wong GC, et al. Middle age cardiovascular risk factors and abdominal aortic aneurysm in older age. Hypertension 2003;42:61–68

Brown LC, Powell JT. Risk factors for aneurysm rupture in patients kept under ultrasound surveillance: UK Small Aneurysm Trial Participants. Ann Surg 1999;230:289–296

Vardulaki KA, Walker NM, Day NE, et al. Quantifying the risks of hypertension, age, sex and smoking in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm. Br J Surg 2000;87:195–200

Brady AR, Thompson SG, Fowkes FG, et al. UK Small Aneurysm Trial Participants: abdominal aortic aneurysm expansion: risk factors and time intervals for surveillance. Circulation 2004;110:16–21

Kertai MD, Boersma E, Westerhout CM, et al. Association between long-term statin use and mortality after successful abdominal aortic aneurysm surgery. Am J Med 2004;116:96–103

Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA 2003;289:2560–2572

Genuth S, Alberti KG, Bennett P, et al. Follow-up report on the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2003;26:3160–3167

Third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on detection, evaluation and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Circulation 2002;106:3143–3421

Wilmink A, Hubbard C, Day N, Quick C. The incidence of small abdominal aortic aneurysms and the change in normal infrarenal aortic diameter: implications for screening. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2001;21:165–170

Gibbons RJ. ACC/AHA Guidelines for exercise testing: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines (Committee on Exercise Testing). J Am Coll Cardiol 1997;30:260–315

Bruce RA. Exercise testing methods and interpretation. Adv Cardiol 1978;24:6–15

Kligfield P. Heart rate adjustment of ST segment depression for improved detection of coronary artery disease. Circulation 1989;79:245–255

Okin P. Heart rate adjustment of exercise-induced ST segment depression: improved risk stratification in the Framingham Offspring Study. Circulation 1991;83:866–874

Gerson C. Exercise-induced U-wave inversion as a marker of stenosis of the left anterior descending coronary artery. Circulation 1979;60:1014–1020

Wilson PW, D’Agostino RB. Levy D, et al. Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation 1998;97:1837–1847

Conroy RM, Pyorala K, Fitzgerald AP, et al. Estimation of ten-year risk of fatal cardiovascular disease in Europe: the SCORE project. Eur Heart J 2003;24:987–1003

American Heart Association. 2000 Heart and Stroke Statistical Update. Dallas, TX, American Heart Association 1999

Perry IJ, Collins A, Colwell N, et al. Established cardiovascular disease and CVD risk factors in a primary care population of middle-aged Irish men and women. Ir Med J 2002;95:298–310

Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel II.00I). JAMA 2001;285:2486–2497

Grundy SM, Pasternak R, Greenland P, et al. Assessment of cardiovascular risk by use of multiple-risk-factor assessment equations: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology. Circulation 1999;100:1481–1492

Collins R, Peto R, MacMahon S, et al. Blood pressure, stroke, and coronary heart disease. Part 2. Short-term reductions in blood pressure: overview of randomised drug trials in their epidemiological context. Lancet 1990;335:827–838

Kannel WB, McGee DL. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease: the Framingham Study. JAMA 1979;241:2035–2038

Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 1993;329:977–986

World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2003: Shaping the Future. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2003

Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Lancet 1994;344:1383–1389

The Long-Term Intervention with Pravastatin in Ischemic Disease (LIPID) Study Group. Prevention of cardiovascular events and death with pravastatin in patients with coronary heart disease and a broad range of initial cholesterol levels. N Engl J Med 1998;339:1349–1357

Grundy SM, Balady GJ, Criqui MH, et al. Primary prevention of coronary heart disease: guidance from Framingham: a statement for healthcare professionals from the AHA Task Force on Risk Reduction. Circulation 1998;97:1876–1887

Jackson R, Lawes CM, Bennett DA, et al. Treatment with drugs to lower blood pressure and blood cholesterol based on an individual’s absolute cardiovascular risk. Lancet 2005;365:434–441

Topol EJ, Lauer MS. The rudimentary phase of personalised medicine: coronary risk scores. Lancet 2003;362:1776–1777

Eidelmann RS, Hebert PR. Weisman SM, et al. An update on aspirin in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:2006–2010

Joint British recommendations on prevention of coronary heart disease in clinical practice: British Cardiac Society, British Hyperlipidemia Association, British Hypertension Society, British Diabetic Association. Heart 1998;80(suppl 2):S1–S29

Preventing coronary heart disease in high risk patients. In National Service Framework for Coronary Heart Disease. London, Department of Health, 2000;1–32

Haq IU, Ramsay LE, Yeo WW, et al. Is the Framingham risk function valid for northern European populations? A comparison of methods for estimating absolute coronary risk in high risk men. Heart 1999;81:40–46

Spin JM, Prakash M, Froelicher VF, et al. The prognostic value of exercise testing in elderly men. Am J Med 2002;112:453–459

Aktas MK, Ozduran V, Pothier CE, et al. Global risk scores and exercise testing for predicting all-cause mortality in a preventive medicine program. JAMA 2004;292:1462–1468

Froelicher VF, Fearon WF, Ferguson CM, et al. Lessons learned from studies of the standard exercise ECG test. Chest 1999;116:1442–1451

Pilote L, Pashkow F, Thomas JD, et al. Clinical yield and cost of exercise treadmill testing to screen for coronary artery disease in asymptomatic adults. Am J Cardiol 1998;81:219–224

Kurvers HA, Van der Graf Y, Blankensteijn JD, et al. Screening for asymptomatic internal carotid artery stenosis and aneurysm of the abdominal aorta: comparing the yield between patients with manifest atherosclerosis and patients with risk factors for atherosclerosis only. J Vasc Surg 2003;37:1226–1233

Halliday A, Mansfield A, Marro J, et al. MRC Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial (ACST) Collaborative Group. Prevention of disabling and fatal strokes by successful carotid endarterectomy in patients without recent neurological symptoms: randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2004;363:1491–1502

Lloyd GM, Newton JD, Norwood MG, et al. Patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm: are we missing the opportunity for cardiovascular risk reduction? J Vasc Surg 2004;40:691–697

Earnshaw JJ, Shaw E, Whyman MR, et al. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysms in men. BMJ 2004;328:1122–1124

Acknowledgments

The Blackrock Clinic is a privately run hospital affiliated with physicians in St. Vincent’s University Hospital. Dr. Frances Sheehan is a shareholder in its Department of Preventative Medicine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Waterhouse, D., Cahill, R., Sheehan, F. et al. Concomitant Detection of Systemic Atherosclerotic Disease while Screening for Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. World J. Surg. 30, 1350–1359 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-005-0604-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-005-0604-x