Abstract

Climate change is one of the primary environmental problems broadly discussed in the Paris Agreement. In the literature, authors mainly focused on the changes in climate change concern. However, it is more important to answer whether the changes in concerns and responsibilities affect climate-friendly behaviour. Therefore, this study’s objective was to analyse the changes in climate change concern, personal responsibility, and climate-friendly behaviour in EU-28 from 2015 (the launch of the Paris Agreement) to 2019 and evaluate how these changes contributed to separate actions. The changes in climate change concern and personal responsibility were statistically significant (F value). During the analysed period, the purchase of energy-efficient appliances increased the most. Meanwhile, the usage of environmentally friendly transport alternatives decreased. The determinants of changes in climate-friendly behaviour were identified using the multiple linear regression model. Results showed that changes in climate change concern significantly and positively affected waste management and choice of energy supplier which offers a greater share of energy from renewable sources and purchased of low-energy homes. Meanwhile, personal responsibility significantly and positively influenced switching energy suppliers but had a negative effect on home insulation. Furthermore, residents who performed high-cost behaviours (purchase of low-energy homes) also switched energy suppliers and insulated their homes. Therefore, the results indicated that the benefit and cost of behaviour (time, money) are very important aspects to promote climate-friendly behaviour. This study suggested that policymakers should raise public awareness about climate change and take all efforts to reduce the cost of high-cost behaviours and enable the possibilities to perform climate-friendly behaviour.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

To avoid a rise in global temperatures above the 2 °C threshold, 195 countries reached a historic agreement on climate change to set out a global action plan to combat climate change and the potentially catastrophic effects in 2015. Therefore, governments worldwide are making efforts to decarbonise their economies, on which other important aspects depend: health and public services, local and national economic changes, employment management, security and public order and the fight against poverty. The EU was the first country group committed to reducing greenhouse gas emission under the Paris Agreement. According to European Council meeting (10-11 December 2020) conclusions, the EU’s current and latest target is to reduce its CO2 emissions 55% by 2030, compared to 1990 levels. However, increasingly more authors (Bauer and Mendrad 2019) have emphasised that economic and political aspects and individual contributions are very important in the fight against climate change. People behaving in climate change-friendly mode could significantly mitigate emission levels (Barr et al. 2011). Society´s role in climate change was highlighted in the Paris Agreement (UN Framework Convention on Climate Change 2015). One of the best examples of the importance of society in controlling climate change is the 26th United Nations Climate Change conference (COP26), originally scheduled for November 2020. However, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, it was rescheduled to 2021. Although the conference was postponed for a year, it is planned to be exploited (to increase climate ambitions in NDCs), there is no “pause” in the household sector’s contribution to global warming. On the contrary, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the importance of households increases further due to the continuous activity of residents in their homes.

In the most recent decade, the research on climate change and changes in climate change concern, scepticism, and perception and the main determinants were very extensive (Whitmarsh 2011; Brulle et al. 2012; Scruggs and Benegal 2012; Pidgeon 2012; Franzen and Vogn 2013; Capstick et al. 2014; Whitmarsh and Capstick 2018; Visschers 2017; Lawson et al. 2019; Druckman and McGrath 2019 and others). However, how changes in concern contribute to climate-friendly behaviour was not analysed by previous researchers to the best of our knowledge. Furthermore, environmental concern alone is not enough, as many situational barriers and psychological obstacles prevent attitudes from translating into pro-environmental behaviour (Gifford 2011). The question has arisen whether concerns and responsibilities affect behaviour and climate change. Therefore, it is necessary to assess the impact of climate change concerns and the responsibility level, which is usually associated with behaviour. An increasing number of studies (Skogen et al. 2018; Austin et al. 2020; Bouman et al. 2020; Boto-Garcia and Bucciol 2020; Jakučionytė-Skodienė and Liobikienė 2021) reveal that the individual level of concern or responsibility is an important factor to promote climate-friendly behaviour. However, the changes in personal responsibility and its impact on climate-friendly behaviour were not analysed, to the best of our knowledge. This analysis reveals whether the changes in climate change concern and the level of personal responsibility are related and how they contribute to climate-friendly behaviour.

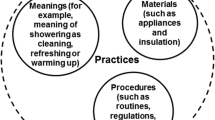

Climate-friendly behaviour encompasses different areas: energy conservation behaviour, willingness to use or to select (or willingness to pay more) renewable energy, usage of environmentally friendly transportation, and purchase of green products. In the literature, many authors (Tabi 2013; Motawa and Oladokun 2014; Štreimikienė 2015; Wei et al. 2016; Pothitou et al. 2016; Wakiyama and Kuramochi 2017; Paco and Lavrador 2017; James and Ambrose 2017; Baul et al. 2018) considered the climate-friendly behaviour encompassing all types of behaviour. However, due to the different benefits and costs, the concern and responsibility unequally influence climate change mitigation behaviour (Jakučionytė-Skodienė and Liobikienė 2021). Therefore, analysing the determinants of climate-friendly behaviour, it is very important to consider, particularly, the costs of behaviour (Van Borgstede et al. 2013; Moore and Boldero 2017; Jakučionytė-Skodienė and Liobikienė 2021; Liobikienė and Minelgaitė 2021). By encompassing actions with different costs (from purchasing a new home to reducing waste), we analysed whether the changes in climate change concern and responsibility equally determined these separate actions. Furthermore, exploring actions separately, we analysed whether the changes in one action influence the changes in other actions. Therefore, the objective of this paper is to analyse the changes in climate change concern, responsibility assumption and climate-friendly behaviour in all EU countries from 2015 (the launch of the Paris Agreement) to 2019 and to evaluate how these changes contribute to separate climate-friendly behaviours. Thus, this study initiates the development of studies related to climate change and climate-friendly behaviour considering the temporal aspect.

Literature Review

Changes in Climate Change Concern and Assumption of Personal Responsibility

Climate change concern defines attitudes towards the importance of climate change. In the literature, authors vastly analysed the changes in concern related to climate change and the primary determinants as extreme weather events, such as floods, drought (Spence et al. 2012; Ng et al. 2015), extreme heat (Bi et al. 2011), storms and sea-level rise (Austin et al. 2020); media coverage (information dissemination about climate change); accuracy of scientific information; elite cues; movement against climate change; economic policies (Grafton et al. 2012; Ohler and Billger 2014), and changes in economic activity and political situation (Lachapelle et al. 2012; Tranter 2013). Other studies on public perceptions regarding potential climate change have focused on socio-political factors such as political ideology (McCright et al. 2016) and socio-demographic variables (Alston and Kent 2008; McCright and Dunlap 2011; McCright et al. 2016). However, what changes in climate change concern was observed after the Paris Agreement when this problem was greatly spread worldwide, was not included by previous authors.

Furthermore, this study’s primary focus was how the climate change concern changed among EU countries, which are the leaders solving the climate change problem at the political level. Previous authors usually analysed the climate change concern in separate EU countries or groups of several countries (Dienes 2015; Nauges and Wheeler 2017; Frondel et al. 2017; Poortinga et al. 2019; Douenne and Fabre 2019; Boto-Garcia and Bucciol 2020; Bouman et al. 2020). Therefore, this study reveals whether the concern changed equally in all EU countries. Lo (2016) revealed that richer countries, particularly those with the ability to deal with climate change adoption, are less concerned in general. In this paper, we are not going to analyse the possible factors of these changes. We focused on how these changes contribute to the assumption of personal responsibility and climate-friendly behaviour.

Assumption of the responsibility reflects the extent to which individuals feel capable of and compelled to take useful action toward a desired result, and it prompts a willing, proactive engagement in an issue that can generate progress and future accomplishment (Fuller et al. 2006). Reviewing the studies concerning the assumption of responsibility, authors primarily focused on its determinants. Several studies (Schultz and Zelezny 2003; Boto-Garcia and Bucciol 2020) indicated that responsibility is positively related to openness and self-transcendence but negatively associated with conservation and self-enhancement. Other authors (Hersch and Viscusi 2006; Zsoka et al. 2013; Boto-Garcia and Bucciol 2020) emphasise that assumption of climate change responsibility is determined by gender, age, education, religiosity, and income. Bateman and O’Connor (2016) analysed how political orientation influenced responsibility for climate change mitigation and adaptation. However, the changes in the assumption of responsibility were not analysed to the best of our knowledge.

The changes in concern related to climate change and responsibility can differ. People can be very concerned, but they can believe that this problem can be solved by politics. Thus, citizens could also believe that they are not responsible and could not contribute to the mitigation of the climate change problem. Therefore, it is important to analyse whether the level of responsibility also changed after the Paris Agreement in the separate EU countries and how it is related to changes in climate change concern.

The Changes in Climate-friendly Behaviour and Impact of Climate Change Concern and Assumption of Responsibility

Human behaviour is particularly related to the solving of environmental problems, and drastic changes in unsustainable behaviour are crucial to mitigate climate change (Williamson et al. 2018). There is an increasing focus on pro-environmental behaviour and its relationship to CO2 emissions. Many authors (Štreimikienė 2015; Pothitou et al. 2016; Wei et al. 2016; Paco Lavrador 2017) showed that pro-environmental behaviour correlates with household energy savings and CO2 emissions. Therefore, people are asked to alter their behaviours with the intent of reducing the harmful impact on the environment (De Leeuw et al. 2015). Consumers could play a huge role via behaviour on climate change mitigation (Barr et al. 2011). Therefore, the issue of how to promote climate-friendly behaviour remains. In this study, we analysed whether changes in climate-friendly behaviour occurred between adoption of the Paris Agreement and 2019 and how changes in concern related to climate change and the assumption of responsibility contribute to these changes. Concern (sometimes expressed as worry) and personal responsibility lead individuals to undertake more specific actions to reduce climate change (Bateman and O’Connor 2016; Van der Linden et al. 2017). This is why these two factors are closely related and have a significant impact on behaviour.

Albrecht (2011) emphasises that worries and concerns about climate change can contribute to distress resulting from environmental change. Climate change is not only about climate change as a problem, but about the things and issues that it will harm or take away from us (Wang et al. 2018). Howell et al. (2016), Evans et al. (2014) and Carrico et al. (2015) indicated that citizens with different concerns related to climate change levels react differently to communications with adaptation and mitigation frames. Many authors (Zaval et al. 2014; Kaesehage et al. 2014; Van der Linden et al. 2017) indicated that individuals’ concerns are among the most important factors in mitigation behaviour. Wheeler et al. (2013) consider the potential endogeneity between climate change concern and water-saving behaviour on Australian irrigators’ adaptation planning. Analysing eleven OECD countries, Nauges and Wheeler (2017) found that climate change concerns positively and significantly influenced water and energy mitigation behaviour. However, other authors stated that most respondents have not worried about the climate change problems (Gifford et al. 2011; Weber and Stern 2011). Kuthe et al. (2019) found an insignificant relationship between concern and action related to climate change. Furthermore, citizens hold different perspectives, and views vary significantly. Despite the viewpoint and belief, inaction prevails even among those who take climate change seriously (Weber and Stern 2011). It could depend that pro-environmental behaviour involves considerable costs (time, inconvenience level, money) the lack of joyless existence. Alternatively, engaging in costly behaviour has repeatedly been associated with happiness benefits (Kasser and Zhao 2017). Therefore, Steg et al. (2014) stated that pro-environmental behaviours can be more time-consuming, expensive, and less pleasurable than other behaviour alternatives. Therefore, analysing the impact of climate change concerns, it is very important to consider the cost of behaviour.

Felt responsibility helps individuals understand that they need to do something, rather than believing that someone else will do it. Therefore, increasingly more authors (Rickard et al. 2014; Bouman et al. 2020; Boto-Garcia and Bucciol 2020; Jakučionytė-Skodienė and Liobikienė 2021) revealed that not only concerns but also taking personal responsibility for climate change are key determinants of pro-environmental behaviour and beliefs concerning personal responsibility may affect actual behaviour. Bateman and O’Connor (2016) considered that the polluter pays principle is central to responsibility. Brügger et al. (2015) argued that perceived responsibility is necessary for climate change in general and mitigation and adaptation. Previous research (Rezaei et al. 2019; Bouman et al. 2020) also has shown that pro-environmental intention can be predicted more accurately by integrating responsibility into the model. Kaiser and Scheuthle (2003) revealed a positive correlation between responsibility and pro-environmental behaviour among Swiss residents. Bouman et al. (2020) tested the relationships between the beliefs of 22 European countries’ residents’ personal responsibility to mitigate climate change and showed a statistically significant relationship between personal responsibility and energy-saving behaviours. However, Jakučionužytė-Skodienė and Liobikienė (2021) revealed that the impact of responsibility on climate-friendly behaviour depends on the cost of behaviour as well. The question remains how the changes in personal responsibility influence separate actions to solve the climate change problem.

Data and Methods

The analysis of concern related to climate change and personal responsibility changes in the EU has been performed based on the five Eurobarometer surveys (75.4; 80.2; 83.4; 87.1; 91.3 performed in June 2011; November-December 2013; May-June 2015; March 2017 and April 2019 respectively). Meanwhile, based on an analysis of changes in concerns and responsibilities over these five years, climate-friendly behaviour was examined only from the Paris Agreement (2015) until the last research period in 2019. During the surveys, respondents were questioned face-to-face in respondents’ homes and in the appropriate national language. The same questions were asked in all EU countries throughout the study period. Respondents from age 15 and over were chosen as the target group. A number of sampling points were evaluated in each country according to probability proportional to population size and population density. The detailed interviews’ confidence intervals and methods are provided in reports by the European Commission (EC 2011–2019). The surveys in all 28 EU (according to the 2019 list) countries were representative. In the study, these countries: Austria (AT), Belgium (BE), Bulgaria (BG), Cyprus (CY), Czech Republic (CZ), Denmark (DK), Estonia (EE), Spain (ES), Finland (FL), France (FR), Germany (GE), Greece (GR), Croatia (HR), Hungary (HU), Ireland (IE), Italy (IT), Latvia (LV), Lithuania (LT), Luxemburg (LU); Malta (MT), the Netherlands (NL), Poland (PL), Portugal (PT), Romania (RO), Slovakia (SK), Slovenia (SL), Sweden (SE), and United Kingdom (UK) were included.

The questions presented in Table 1 were used to assess climate change concern, personal responsibility assumption and climate-friendly behaviour. The concern level related to climate change was assessed using a scale from one (“not at all a serious problem”) to ten (“an extremely serious problem”). Personal responsibility and climate-friendly behaviour were measured using dichotomous values.

The mean score and standard deviation of the respondents' climate change concern, responsibility assumption and climate-friendly behaviour are presented at Appendix A. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to assess the effect of the analysed years on the average perception level. Significant differences between the analysed years and perception level were determined by the Student t test, and p < 0.05 was considered significant. The x2 criterion was used to evaluate the dependence of analysed years on responsibility level. The changes in personal responsibility level and climate-friendly behaviour were calculated by the difference between 2015 and 2019. The percentage difference was used to calculate the changes in concern of the same year. To assess the relationship between changes in climate change concern and responsibility, we used Spearman correlation analysis.

The determinants of changes in climate-friendly behaviour were identified using the multiple linear regression (MLR) model. According to Rath et al. (2020) MLR model is the most widely applied method when the dependent variable (target variable) is dependent on many independent variables. The MLR model assumes a linear relationship between the response variable Y and the predictor variables x1, x2, …, xn. This analysis shows which factor determined the changes in separate action the most. The normality was checked using probability plots of residuals and by applying Shapiro–Wilk test. The collinearity test was evaluated applying variance inflation factor statistics. The latter assumptions of regression analyses were satisfied. The distribution of residuals was random. The regression analysis coefficients beta (β) and p values were assessed to show what factors influenced changes in climate-friendly behaviour.

Results and Discussion

Changes in Climate Change Concern and Personal Responsibility

Climate change concern have been changed across the EU-28 in 2011–2019 (Fig. 1). One-way ANOVA showed that among the separate time the climate change concern differed statistically significant (F = 431.68; p < 0.001). However, since 2011 there has been a noticeable decrease in the average of climate change concern level until 2013. Meanwhile between 2013 and 2015 the level of climate change concern changed insignificantly. The climate change concern in the EU-28 have been particularly acute since 2015. The year of 2015 is particularly important considering climate change policy whereas in this year the Paris Agreement was launched. Therefore, in this study the period 2015–2019 was analysed. During this period the climate change concern grew statistically significancy and from 2015 to 2019 concern in EU countries increased from 7.24 to 7.86 respectively. These changes could depend on the extensive information dissemination about climate change particularly after Paris Agreement period, movements against climate change and extreme weather events.

The share of personal responsibility in the EU-28 also significantly differed in separate years (x2 = 1664.01, p < 0.001). Meanwhile, focusing on the 2011–2013 changes, the share of personal responsibility increased while the climate change concern decreased. However, in 2015 the share of personal responsibility was the least. It could be that people expected that the governments that committed to solving this problem could mitigate climate change. However, without personal responsibility, it is difficult to achieve enough reduction in greenhouse emissions. Furthermore, not all governments are climate-friendly, as the United States withdrew from Paris Agreement during Donald Trump’s presidency. Therefore, in 2015–2019 the share of responsibility in the EU increased by 1.7 times (Fig. 2). These results reveal that EU countries have not only become more aware of the seriousness of the problem of climate change during this period but are also more inclined to take responsibility for climate change.

Therefore, the changes in concern related to climate change and personal responsibility could occur if policymakers take major efforts to agree on internationally binding global climate targets and these examinations led to the Paris Agreement. It is generally accepted that individuals’ contributions to climate change targets are very important, and surveys (Steenjes et al. 2017) in the EU revealed people’s connectedness to the Paris Agreement and the perceived necessity of the agreement’s goals. Some authors (Joss et al. 2015; Flurin 2017) emphasise the importance of “Agenda 21”, which introduced new governance relationships between citizens. The level of ambition of “Agenda 21” policy implemented in the EU is successfully related to the rise in awareness on sustainability and to the growth of participation of local civil society (Jänicke 2017). Moreover, Steenjes et al. (2017) found that students are likely to be personally involved in the Paris Agreement. Consequently, the Paris Agreement initiated a greater amount of information on climate change and increased awareness of this serious ecological problem.

The growth of concern related to climate change and personal responsibility also could be related to the Greta Thunberg phenomenon. This is the largest youth movement in history, leading to school strikes and wider climate strikes across the world (Fridays for Future. 2020). After that, 7.6 million people and organisations took part in a Global Climate Strike in September 2019 (Global Climate Strike 2019). This established one of the largest social-environmental movements to date. These social movements may have further contributed to the development of information on climate change and climate change perception as a very serious problem, which has increased the personal responsibility for climate change.

The Correlation between Changes in Climate Change Concern and Personal Responsibility

Changes in concern related to climate change varied among EU-28 countries during 2015–2019 (Fig. 3). The largest changes were indicated in the United Kingdom, Estonia, and Denmark. While the smallest changes were in Austria, Italy, and Greece. In Bulgaria, the level of concern was rather the same in 2015 and 2019. In Romania, the level of climate change concern was reduced during this period. Therefore, the level of concern was reduced only in one country of EU-28. Furthermore, the change in climate change concern was significantly related to the initial level (in 2015) of concern. In countries where the level of concern was the least, climate change concern increased the most, and vice versa; in countries where the level of concern related to climate change was the highest, the changes were the smallest. These results reveal that all EU countries have become more aware of the climate change problem. Baiardi and Morana (2021) also indicated that climate change concern in Europe has increased over the last decade and significant effect are found for education, media coverage, social trust and relative power position of right-wing parties in government. Some authors (Nisbet and Myers 2007; Boykoff and Yulsman 2013) emphasises that public concern about climate change has risen recently due to growing scientific evidence and higher mass media coverage and political debate. Therefore, the current challenge for policymakers should be to further expand information on climate change in order to keep the growing trend of climate change concerns in the future.

In terms of share of personal responsibility, the biggest change was observed in the United Kingdom (Fig. 4). Therefore, in this country, concern and responsibility levels increased the most. This may be related to the increased flow of media information on climate change and its real consequences (particularly the frequency and scale of rising wildfires in the last decade in the UK). Some authors (Lachapelle et al. 2012; Tranter 2013) confirms that information on climate change plays a key role in enhancing personal responsibility. In Slovakia, France, and Romania, the share of personal responsibility increased the most as well. Interestingly, during this period in the latter country, the concern level decreased, but responsibility increased the most. This could be because the concern level was rather high in this country, but the responsibility level was one of the smallest. In 2015 only 8% of respondents stated that they assume personal responsibility to solve Romania’s climate change problem. The smallest changes in the share of personal responsibility were observed in Cyprus and Hungary. Meanwhile, in Bulgaria, the share of responsibility decreased during the analysed period. Therefore, in Bulgaria, the change in climate change concern was negligible and reduced responsibility where the share was also rather low. Furthermore, the relationship between changes in the share of personal responsibility and the initial level was insignificant. This result reveals that the changes in personal responsibility did not depend on the initial share of responsibility. In countries where the share of responsibility was low, it did not necessarily increase the most.

Analysing the relationship between changes in the share of personal responsibility and climate change concern, the correlation coefficient was significant and positive (Fig. 5).

Consequently, the growing concern about climate change in the EU has also led to a growing personal responsibility assumption for climate change. These findings are confirmed by Bouman et al. (2020), who have shown in their study that growing worry and responsibility for climate change are leading to more environmentally friendly behaviour in many EU countries. This aspect is very positive, whereas the promotion of awareness could also increase the personal responsibility assumption and thus could increase the chance of implementing climate-friendly behaviour. It is very important that people become not only very concerned about climate change but also understand that they need to personally contribute to the mitigation of climate change.

Changes in Climate-friendly Behaviour and Its Factors

Changes in separate climate-friendly behaviours varied among EU-28 countries during the period of 2015–2019. Climate-friendly behaviours attributed to the lowest cost were waste reduction and recycling which increased by 1.8% from 2015 to 2019 in the EU (Fig. 6). Importantly, these climate-friendly behaviours were the most chosen in the EU. The results could be related to the development of information and infrastructure for waste management in almost all EU countries, and recycling does not involve additional costs for the residents (Jakučionytė-Skodienė and Liobikienė 2021; Minelgaitė and Liobikienė 2019). Furthermore, to achieve the Paris Agreement goals on waste management, EU countries have adopted new EU policies and strategies (Saheb et al., 2018). Many studies have shown the positive impact of the deposit-refund system on reducing the inappropriate dumping of waste in the EU (Linderhof et al. 2019; Abejon et al. 2020). A particularly positive change in recycling was observed in Croatia (16.7%) and the Baltic states: Latvia (12.9%), Lithuania (9.7%), and Estonia (8.7%) (Appendix B). Meanwhile, there have been significant negative changes in Ireland, Austria, and Bulgaria (−12.9; −8.7; −6.7%).

The purchasing of a new energy-efficient household appliance increased by 7% from 2015 to 2019 in the EU-28, and it was the largest positive change of all climate-friendly behaviours (Fig. 6). This may be because residents have become more responsible for their daily choices, which further increases their performance. Moreover, according to International Energy Agency (IEA 2019), since 2015, improvements in global energy intensity have been weakening each year. Consequently, the Paris Agreement had a significant impact not only on politicians but also on manufacturers of new devices. Industry is committed to producing energy-efficient goods. Greater diffusion of the climate change problem has also led to higher demand for more energy-efficient devices. In Netherlands and Portugal, this behaviour increased the most (by 17.6%; 14.7% respectively), while the smallest change in this behaviour was found in Sweden and Finland (by 0.2%; 0.5% respectively) (Appendix B). However, the smallest change is not related to the higher purchase of energy-efficient appliances in 2015–2019. Despite the largest change, the highest purchases were also found in the Netherlands as opposed to the latter countries over the entire period. However, not all climate-friendly behaviours increased during the study period. The choice of environmentally friendly alternatives to using private cars decreased by 1.2% in the EU-28. This result may be because choosing an alternative to a personal car is inconvenient and requires more effort (Jakučionytė-Skodienė and Liobikienė 2021). Moreover, this type of behaviour could be attributed to high-cost behaviour in the same way as purchasing new cars (Van Borgstede et al. 2013). Although this action has declined in many EU countries (Austria, Latvia, Estonia, Luxembourg, and others). In the United Kingdom, Malta, and Germany, this behaviour significantly increased (8.6%; 8.6%; 7.7%, respectively).

Most countries in the EU insulated their homes better to reduce energy consumption. The change in this behaviour increased by 1.4% during the study period (Fig. 6). The largest positive change in insulating homes was seen in Cyprus and Greece (by 10.4%; 7.1%, respectively), while the smallest increases in this behaviour were in Poland and Finland (0.2%; 0.4%, respectively) (Appendix B). It can depend on the fact that climate change has led to a colder than usual winter period in the countries closer to the equator and warmer winters in the Nordic countries, such as Poland and Finland. Moreover, lower energy consumption for heating leads to lower costs, which is also very important for many consumers (Romanach et al. 2017). These factors increase the real ability to take personal responsibility for climate change and invest in home insulating.

The choice of energy suppliers offering more energy from renewable sources increased by as much as 2% during this period in the EU-28 (Fig. 6). Particularly, the largest positive change in this behaviour was seen in Germany and Denmark (by 8.5%; 6.3% respectively), and it could be related to the large number of offers of a greener energy supplier or, in general, the possibility to choose another supplier (Appendix B), while a negative change was observed in Luxembourg, Austria, Cyprus, Ireland, Czech Republic, Estonia, Lithuania, Poland, and Croatia. The reduction of this behaviour could be related to the fact that in 2015 they had already chosen similar suppliers, and in 2019, they simply did not get better conditions or just choosing another energy supplier is too expensive financially. Furthermore, in some EU countries, it is not yet possible to choose an energy supplier. Jakučionytė-Skodienė et al. (2021) indicated that individuals in Lithuania have scarce possibilities to choose an electricity supplier, and an option to choose green energy could not be implemented (except the private houses). The role of policy is particularly important in implementing this climate-friendly behaviour, and the choice of energy supplier should be ensured in all EU-28 countries.

As well as the choice of environmentally friendly alternatives to using a private car, the purchases of a new car with lower fuel consumption have also decreased 1.2% in the EU-28 during this period (Fig. 6). Therefore, the choice of environmentally friendly alternatives to using a private car and the purchases of a new car with lower fuel consumption are potentially related, and they are both classified as high-cost behaviours due to benefit and cost aspects (time, money). However, the largest positive change (7.8%) in the purchase of new cars was found in Latvia, but the country’s transportation alternatives decreased during the study period (Appendix B). However, Malta and the United Kingdom in the EU are leading the way in choosing an alternative to the car, although the change in the purchase of a new car with lower fuel consumption is negative (−11.7%; −4%, respectively). Such differences suggest that, despite the growing concern about climate change and personal responsibility assumption in EU-28, in many cases, these two types of behaviour in countries are not chosen together because of different benefits and costs, and sometimes, the price of a new car or fuel is offset by the search for new alternatives to travel, or by countries. Therefore, policymakers should not only ensure the development of information about climate change and ways to mitigate it but also decrease the costs of high-cost behaviours and increase the availability of their implementation.

Climate-friendly behaviour which could be attributed to the highest cost as purchasing a low-energy home, was the least performed in the EU-28 during 2015–2019 (Fig. 6). Although low-energy homes are beneficial not only for the environment but also financially (lower energy consumption). Furthermore, these behaviours are very expensive, and only a small percentage of individuals can afford to perform these behaviours (Romanach et al. 2017; Jakučionytė-Skodienė and Liobikienė 2021). In many European countries (Romania, Slovakia, Estonia, Hungary, Belgium, and others), this action’s performance decreased (Appendix B). Only a few countries (Denmark, France) had a greater positive change in this behaviour (by 3.6%; 2.5%, respectively). However, to achieve the Paris Agreement goals, the European Commission is urging the member states to implement nearly zero energy strategies is in accordance with requirements of the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive so that all new buildings are net zero carbon by 2030 (UK pogramme 2019). Therefore, in the near future, the speed of construction of these houses could increase, and one of the primary policy tasks should be to improve access to these homes for the residents (financing, cost).

Increases in climate change concern and personal responsibility are necessary. However, the increase in climate-friendly behaviour is more important. Analysing the determinants of these behaviour changes, regression analyses showed that climate-friendly behaviour could be attributed to the lowest cost as changes in reducing waste and recycling depended on buying new energy-efficient appliances (Table 2). While both are considered low-cost behaviours, the reasons residents chose them are different. The changes in the purchase of energy-efficient appliances did not depend on climate change concerns and personal responsibility assumption changes. Therefore, it can be concluded that the increase in this action is related to the increasing supply of energy-efficient appliances. Meanwhile, changes in waste reduction and recycling depended on changes in concern about climate change. Schill et al. (2020) have also shown that waste management at the household level depends on environmental concerns. Although waste management depends on climate change concerns, personal responsibility for climate change did not lead to this behaviour. Furthermore, the changes in waste reduction behaviour significantly but negatively depended on changes in the high-cost behaviour such as purchasing low-energy homes. Thus, the more people bought low-energy homes, the less they cared about managing their waste. This may be because waste management is classified as a low-cost behaviour and residents who do not have much money but are concerned about climate change were more willing to take actions related to waste reduction than buying low-energy homes. Therefore, the climate-friendly actions may not only increase each other but due to different performance options, efforts, and costs, the reduction can be observed.

Our study did not identify factors that significantly determine the changes in the choice of pro-environmental alternatives to using private cars (Table 2). This may have been influenced by the decline in this behaviour in the EU-28 in 2015–2019 and regularly use these alternatives requires more effort than cost, increasing the possible causes. Furthermore, the infrastructure of public transport is important as well.

The changes in better home insulation decreased energy consumption significantly but negatively depended on changes in personal responsibility for climate change assumption (Table 2). Therefore, the more individuals were responsible for the climate change problem, the less they were willing to insulate a home better. Despite the increase in EU-28 personal responsibility assumption, these results may have been because many EU residents live in apartment buildings where there is no possibility of insulating their private accommodation or, conversely, the entire apartment building has already been renovated during the study period. However, changes in better home insulation did not depend on changes in climate change concern, but changes in the highest-cost behaviours (buying greener cars and low-energy homes) significantly and positively affected changes in this behaviour. Achtnicht and Madlener (2014) also found that private homeowners who were financially able, for whom it was profitable and favourable, were more likely to undertake building energy retrofit activities in Germany. These results confirm the importance of benefit and cost behaviour (money). Policymakers should not only raise public awareness about climate change but also decrease the cost of high-cost behaviours. Then, these behaviours could increase the performance of low-cost behaviours and by countries. Moreover, better home insulation in apartment buildings is particularly dependent on national policies and governments. The development of apartment building renovation (modernisation) programmes in EU countries should be inseparable from climate change policy’s primary goals.

Regression analysis showed that changes in switching to an energy supplier which offers renewable sources significantly and positively depended on changes in personal responsibility for climate change and significantly but negatively on changes in climate change concern (Table 2). Therefore, the more citizens were concerned about climate change, the less they were willing to switch energy suppliers. Despite the exemplary concern, individuals do not always behave in environmentally friendly mode due to inconvenience and extra efforts (Jakučionytė-Skodienė et al. 2021). Ek and Soderholm’s (2008) study conducted in Sweden showed that the impact of electricity costs and knowledge is crucial for the latter decision, while people who perceive relatively high costs are less likely to switch to a green electricity supplier. Furthermore, the lack of choice of energy supplier also could influence that despite that people are very concerned about climate change they do not switch energy supplier. However, the growing personal responsibility for climate change has led to an increasing choice of renewable energy suppliers, which indicated that climate change concerns and personal responsibility assumptions are not necessarily related and may have different effects on climate-friendly behaviour. Furthermore, the availability to choose an electricity provider is also very important (Jakučionytė-Skodienė et al. 2020) because not all EU-28 countries have it. Changes in switching to an energy supplier that offers a greater share of renewable sources significantly and positively depended on buying a low-energy home. These results may have been because residents who bought a low-energy home had the necessary opportunity to choose a greener energy supplier, or even more, to produce renewable energy in their new homes for themselves (such as solar panels).

One of the highest-cost behaviours related to changes in buying low-fuel cars depended on another high-cost behavioural change—buying low-energy homes (Table 2). Consequently, residents who had the opportunity to buy a new car could afford to buy a low-energy home as well. Moreover, this behaviour did not depend on any low-cost behaviours, which confirms the importance of finance in the performance of climate-friendly behaviours. Changes in concern and personal responsibility did not significantly affect changes in buying low-fuel cars. As a result, residents had the opportunity to purchase a new car, but it could not be assumed that they bought it due to lower pollution. Social status is a more important aspect than environment.

Regression analyses showed that the climate-friendly behaviour could be attributed to the highest cost, as changes in the purchase of a new home significantly depended on changes in climate change concern (Table 2). The results are similar to the study conducted by Kesternich et al. (2019), which finds that homeowners’ willingness to pay for energy efficiency is determined by environmental concerns. The changes in personal responsibility insignificantly influenced this behaviour change. Therefore, the increase in personal responsibility did not contribute to the growth in the purchase of new low-energy homes. Furthermore, the growth of home insulation and the selection of green energy suppliers were significantly related to the increase in low carbon home purchases. Meanwhile, the change in waste reduction behaviour negatively was related to the changes in the high-cost behaviours, such as the purchase of a new home. It could relate to the fact that the changes in these behaviours depended on different reasons. The changes in usage of environmentally friendly transport, purchase of environmentally friendly cars, and energy efficiency appliances negatively but insignificantly influenced the purchase of a new home. These results showed that the purchase of a new home is very specific, and it is difficult to increase this behaviour. The affordability, income, and price level could be some of the primary reasons for high-cost behaviour.

Limitations and Future Directions

In this paper, we analysed not individual but the common EU-28 level climate change concern, personal responsibility assumption, and actions related to climate-friendly behaviour in 2011–2019. This research shows the general trends of EU-28 residents’ awareness about climate change and their real actions contributing to climate change mitigation. However, in future research, climate change concern, personal responsibility, and pro-environmental behaviour should be identified at the individual level, and this would further understand what determines society’s attitude about climate change problem and their contribution to climate change mitigation.

Furthermore, assessing the determinants of climate-friendly behaviour, we did not include economic aspects (country’s level of development or individual household income). It would be important to pay attention to this in future research because each action of climate-friendly behaviour has different costs and benefits.

Conclusions and Policy Implication

Climate change remains one of the most serious environmental problems. In the Paris Agreement, where almost all world countries committed to mitigating this problem, the importance of society’s role in mitigating climate change was highlighted. Moreover, residents’ behaviour is a vital component in climate policies, and it is necessary to know how and to what extent climate-friendly behavioural changes will be mobilised by climate policymaking. Therefore, for successful climate change policy implementation, it is necessary to assess how changes concern and responsibility affected climate-friendly behaviour.

This study’s objective was to analyse the changes in climate change concern, personal responsibility, and climate-friendly behaviour in EU-28 from 2015 (the launch of the Paris Agreement) to 2019 and evaluate how these changes contributed to separate behaviours. Referring to Eurobarometer surveys, climate change concern and personal responsibility grew statistically significantly. The changes in concern and personal responsibility were statistically significant (F value). These results reveal that EU countries have not only become more aware of the seriousness of the problem of climate change during this period but are also more inclined to take responsibility for climate change. This may be related to the launch of the Paris Agreement, which increased the development of information on climate change, encouraged social movements for the quality of the environment, and increased the role of climate change policy.

Changes in separate climate-friendly behaviours differed among EU-28 countries during the period of 2015–2019. Climate-friendly behaviour which could be attributed to the lowest cost as waste reduction and recycling, was the most chosen, while the highest-cost behaviour (buying low-energy homes) was a rare action in the EU. During the analysed period, the purchase of energy-efficient appliances increased the most. Meanwhile, the choice of alternatives to private cars decreased. This study suggested that affordability, efforts, income, and price level could be some of the primary reasons for climate-friendly behaviour, and policymakers should take all efforts to reduce the cost of high-cost actions and enhance the possibilities to perform climate-friendly behaviour.

Analysing the changes in climate change concern, we found that in countries where the level of concern was the least (United Kingdom, Estonia, Denmark), concern about climate change increased the most, and vice versa; in countries where the level of concern was the highest (Austria, Italy, Greece), the changes were the smallest. In terms of the share of personal responsibility, the biggest change was also observed in the United Kingdom, and the smallest changes in the share of personal responsibility were observed in Cyprus and Hungary. Also, our study showed an insignificant relationship between changes in the share of personal responsibility and initial level and a positive and significant relationship between changes in climate change concern and changes in the share of personal responsibility. This aspect is very positive, whereas the promotion of awareness also could enhance the level of responsibility assumption. Therefore, one of the primary tasks of policymakers is that people become not only very concerned about climate change but also understand that they personally contribute to the mitigation of climate change. Understandably information about population impact on climate change and opportunities to reduce it at the individual level is crucial for policymakers.

Considering climate-friendly actions, different factors influenced these behaviours. Regression analysis showed that changes in concern related to climate change significantly and positively affected waste management, choice of energy supplier, which offers green energy and low-energy homes. Meanwhile, personal responsibility significantly and positively affected switching energy suppliers but had a negative effect on home insulation. The results showed that only changes in energy supplier choice were influenced by changes in concern and personal responsibility, while individual effects were different for other climate-friendly actions. Our study revealed that people may be very concerned about climate change but do not take responsibility for certain behaviour due to a lack of opportunities for real actions, as in the case of buying low-energy homes. Therefore, policymakers should provide sufficient conditions (easier access to loans with lower interest rates) to engage in high-cost behaviour. Furthermore, residents who performed high-cost behaviour (purchase of low-energy homes) also switched energy suppliers and insulated their homes. The results indicated that the benefit and cost of behaviour (time, money) are very important aspects to promote climate-friendly behaviour. To increase residents’ positive contribution to climate change mitigation, it is imperative to reduce prices and increase behavioural benefits simultaneously. This should be a fairly important goal of climate change policy.

References

Abejon R, Bala A, Vazqualez-Rowe I (2020) When plastic packaging should be preferred: life cycle analysis of packages for fruit and vegetable distribution in the Spanish peninsular market. Resour Conserv Recycling 155:104666

Achtnicht M, Madlener R (2014) Factors influencing German house owners‘ preferences on energy retrofits. Energy Policy 68:254–263

Albrecht G (2011) Chronic environmental change: emerging ‘psychoterratic syndromes. In: Weissbecker, I, (ed.) Climate Change and Human Well-Being: Global Challenges and Opportunities. Springer, New York, NY: 43–56.

Alston M, Kent J (2008) The Big Dry: the link between rural masculinities and poor health outcomes for farming men. J Sociol 44(2):133–147

Austin KE, Rich LJ, Kiem SA, Handley T, Perkins D, Kelly JB (2020) Concerns about climate change among rural residents in Australia. J Rural Stud 75:98–109

Baiardi D, Morana C (2021) Climate change awareness: empirical evidence for the European Union. Energy Econ 96:105163

Bateman T, O’Connor K (2016) Felt responsibility and climate engagement: distinguishing adaptation from mitigation. Glob Environ Change 41:206–215

Bauer A, Mendrad K (2019) Standing up for the Paris Agreement: do global climate targets influence individuals’ greenhouse gas emissions? Environ Sci Policy 99:72–79

Baul TK, Datta D, Alam A (2018) A comparative study on household level energy consumption and related emissions from renewable (biomass) and non-renewable energy sources in Bangladesh. Energy Policy 114:598–608

Barr S, Shaw G, Coles T (2011) Times for (Un)sustainability? Challenges and opportunities for developing behaviour change policy. A case-study of consumers at home and away. Glob Environ Change 21(4):1234–1244

Bi P, Williams S, Loughnan M (2011) The effects of extreme heat on human mortality and morbidity in Australia: implications for public health. Asia Pac J Public Health 23(2):27–36

Boto-Garcia D, Bucciol A (2020) Climate change: personal responsibility and energy saving. Ecol Econ 169:106530

Bouman T, Verschoor M, Albers JC, Bohm G (2020) When worry about climate change leads to climate action: how values, worry and personal responsibility relate to various climate actions. Glob Environ Change 62:102061

Boykoff M, Yulsman T (2013) Political economy, media, and climate change: Sinews of modern life. Wiley Interdiscip Rev: Clim Change 4:359–371

Brulle RJ, Jenkins JC, Carmichael J (2012) Shifting public opinion on climate change: an empirical assessment of factors influencing concern over climate change in the U.S., 2002-2010. Clim Change 114(2):169–188

Brügger A, Dessai S, Devine-Wright P, Morton AT (2015) Psychological responses to the proximity of climate change. Nat Clim Change 5(12):1031–1037

Capstick S, Whitmarsh L, Poortinga W, Pidgeon N, Upham P (2014) International trends in public perceptions of climate change over the past quarter century. WIREs Clim Change 6(1):35–61

Carrico RA, Truelove BH, Vandenbergh PM, Dana D (2015) Does learning about climate change adaptation change support for mitigation? J Environ Psychol 41:19–29

De Leeuw A, Valois P, Ajzen I, Schmidt P (2015) Using theory of planned behavior to identify key beliefs underlying pro-environmental behaviour in high-school students: Implecations for educational interventions. J Environ Psychol 42:128–135

Dienes C (2015) Actions and intentions to pay for climate change mitigation: environmental concern and the role of economic factors. Ecol Econ 109:122–129

Douenne T, Fabre A (2019) French attitudes on climate change, carbon taxation and other climate policies. Ecol Econ 169:106496

Druckman JN, McGrath MC (2019) The evidence for motivated reasoning climate change preference formation. Nat Clim Change 9:111–119

Ek K, Soderholm P (2008) Households‘ switching behavior between electricity suppliers in Sweden. Uti Policy 16(4):254–261

European Council meeting, 2020. Conclusions – 10 and 11 December 2020. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/47296/1011-12-20-euco-conclusions-en.pdf

Evans L, Milfont LT, Lawrence J (2014) Considering local adaptation increases willingness to mitigate. Glob Environ Change 25:69–75

Fuller BJ, Marler EL, Hester K (2006) Promoting felt responsibility for constructive change and proactive behavior: exploring aspects of an elaborated model of work design. J Organ Behav 27(8):1089–1120

Flurin C (2017) Eco-districts: development and evaluation. A European Case Study. Procedia Environ Sci 37:34–45

Franzen A, Vogn D (2013) Two decades of measuring environmental attitudes: a comparative analysis of 33 countries. Glob Environ Change 23(5):1001–1008

Fridays for Future (2020) Fridays for future. Online: https://fridaysforfuture.org/ (Accessed 14 Feb 2021).

Frondel M, Sommer S, Simora M (2017) Risk perception of climate change: empirical evidence of Germany. Ecol Econ 137:173–183

Gifford R (2011) The dragons of inaction: psychological barriers that limit climate change mitigation and adaptation. Am Psychologist 66(4):290–302

Global Climate Strike. 2019. Global climate strike, Sep. 20–27. Accessed 14 Dec 2021.

Grafton QR, Libecap CG, O’Brien JR, Landry C (2012) Comparative assessment of water markets: insights from the Murray–Darling Basin of Australia and the Western USA. Water Policy 14(2):175–193

Hersch J, Viscusi KW (2006) The generational divide in support for environmental policies: European Evidence. Clim Change 77(1-2):121–136

Howell AR, Capstick S, Whitmars L (2016) hImpacts of adaptation and responsibility framings on attitudes towards climate change mitigation. Clim Change 136:445–461

IEA 2019. Global Energy Review 2019: The latest trends in energy and emissions in 2019. Flagship report – April 2020. https://www.iea.org/reports/global-energy-review-2019.

James M, Ambrose M (2017) Retrofit or behaviour change? Which has the greater impact on energy consumption in low income households? Procedia Eng 180:1558–1567

Jakučionytė-Skodienė M, Liobikienė G (2021) Climate change concern, personal responsibility and actions related to climate change mitigation in EU countries: cross-cultural analysis. J Clean Prod 281:125189

Jakučionytė-Skodienė M, Dagiliūtė R, Liobikienė G (2020) Do general pro-environmental behaviour, attitude, and knowledge contribute to energy savings and climate change mitigation in the residential sector? Energy 193:116784.

Jänicke M (2017) The multi-level system of global climate governance – the model and its current state: the multi-level system of global climate governance. Environ Policy Gov 27(2):108–121

Joss S, Cowley R, de Jong M, Muller B, Park BS, Rees WE, Roseland M, Rydin Y (2015) Tomorrow’s city today: prospects for standardising sustainable urban development. London: University of Westminster. ISBN: 978-0-9570527-5-8, p. 52

Kaesehage K, Leyshon M, Caseldine C (2014) Communicating climate change - learning from business: Challenging values, changing economic thinking, innovating the low carbon economy. Fennia 192(2):81–99

Kaiser FG, Scheuthle H (2003) Two challenges to a moral extension of the theory of planned behavior: moral norms and just world beliefs in conservationism. Personal Individ Differences 35(5):1033–1048

Kasser J, Zhao YY (2017) The myths and the reality of problem‐solving. INCOSE 27(1):1114–1124

Kesternich M, Romer D, Flues F (2019) The power of active choice: Field experimental evidence on repeated contribution decisions to a carbon offsetting program. Eur Economic Rev 114:76–91

Kuthe A, Körfgen A, Stötter J, Keller L (2019) Strenghtening their climate change literacy: A case study addressing the weaknesses in young people‘s climate change awareness. Applied Environmental Education and Communication An International Journal 19(2):1–14

Lachapelle E, Boric PC, Rabe B (2012) Public attitudes toward climate science and climate policy in federal systems: Canada and the United States Compared. Rev Policy Res 29(3):334–357

Lawson DF, Stevenson K, Peterson MN, Carrier SJ (2019) Children can foster climate change concern among their parents. Nat Clim Change 9(6):1–5

Linderhof V, Oosterhuis F, Bartelings H, Van Beukering PJH (2019) Effectivenes of deposit-refund systems for household waste in the Netherlands: applying a partial equilibrium model. J Environ Manag 232:842–850

Liobikienė G, Minelgaitė A (2021) Energy and resource-savings behaviours in European Union countries: The Campbell paradigm and goal framing theory approaches. Sci Total Environ 750:141745

Lo AY (2016) National income and environmental concern: observations from 35 countries. Public Underst Sci 25(7):873–890

McCright MA, Dunlap ER (2011) The politicization of climate change and polarization in the American Public’s Views Of Global Warming, 2001-2010. Sociological Q 52(2):155–194

McCright MA, Marquart-Pyatt TS, Shwom LR, Brechin RS, Allen S (2016) Ideology, capitalism, and climate: Explaining public views about climate change in the United States. Energy Res Soc Sci 21:180–189

Minelgaitė A, Liobikienė G (2019) Waste problem in European Union and its influence on waste management behaviour. Sci Total Environ 667:86–93

Motawa I, Oladokun M (2014) A model for the complexity of household energy consumption. Energy Build 87:313–323

Moore HE, Boldero J (2017) Designing interventions that last: a classification of environmental behaviors in relation to the activities, costs, and effort involved for adoption and maintenance. Front Psychol 8:18–74

Nauges C, Wheeler S (2017) The complex relationship between households’ climate change concerns and their water and energy mitigation behaviour. Ecol Econ 141:87–94

Nisbet MC, Myers T (2007) The polls – trends twenty years of public opinion about global warming. Public Opin Q 71:444–470

Ng S, Wood HS, Ziegler DA (2015) Ancient floods, modern hazards: the Ping River, paleofloods and the ‘lost city’ of Wiang Kum Kam. Nat Hazards 75:2247–2263

Ohler MA, Billger MS (2014) Does environmental concern change the tragedy of the commons? Factors affecting energy saving behaviors and electricity usage. Ecol Econ 107:1–12

Paco A, Lavrador T (2017) Environmental knowledge and attitudes and behaviours towards energy consumption. J Environ Manag 197:384–392

Pidgeon N (2012) Climate change risk perception and communication: adressing a critical moment? Risk Anal 32(6):951–956

Pothitou M, Hanna FR, Chalvatzis JK (2016) Environmental knowledge, pro-environmental behaviour and energy savings in households: an empirical study. Appl Energy 184:1217–1229

Poortinga W, Steg L, Bohm G, Whitmarsh L (2019) Climate change perceptions and their individual-level determinants: a cross-European analysis. Glob Environ Change 55:25–35

Rath S, Tripathy A, Tripathy AR (2020) Prediction of new active cases of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic using multiple linear regression model. Diabetes Metab Syndrome: Clin Res Rev 14(5):1467–1474

Rezaei R, Safa L, Damalas CA, Ganjkhanloo MM (2019) Drivers of farmers’ intention to use integrated pestmanagement: integrating theory of planned behavior and norm activation model. J Environ Manag 236:328–339

Rickard NL, Yang JZ, Seo M, Harrison MT (2014) The “I” in climate: The role of individual responsibility in systematic processing of climate change information. Glob Environ Change 26:39–52

Romanach LM, Leviston Z, Jeanneret T, Gardner J (2017) Low-carbon homes, thermal comfort and household practices: uplifting the energy-efficiency discourse. Energy Procedia 121:238–245

Saheb Y, Heinz O, Sandor S (2018) Energy transition of Europe’s building stock. Implications for EU 2030. Sustainable Development Goals. Annales des Mines - Responsabilité et environnement 2018/2 (N° 90), p. 62–67

Schill M, Godefroit-Winkel D, Hogg MK (2020) Young children‘s consumer agency: The case of French children and recycling. J Bus Res 110:292–305.

Schultz WP, Zelezny CL (2003) Reframing environmental messages to be congruent with American Values. Hum Ecol Rev 10(2):126–136

Scruggs L, Benegal S (2012) Declining public concern about climate change: can we blame the great recession? Glob Environ Change 22(2):505–515

Spence A, Poortinga W, Pidgeon N (2012) The psychological distance of climate change. Risk Anal 32(6):957–972

Skogen K, Helland H, Kaltenborn B (2018) Concern about climate change, biodiversity loss, habitat degradation and landscape change: embedded in different packages of environmental concern? J Nat Conserv 44:12–20

Steg L, Bolderdijk JW, Keizer K, Perlaviciute G (2014) An Integrated framework for encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: the role of values, situational factors and goals. J Environ Psychol 38:104–115

Steenjes K, Arnold A, Corner A, Mays C (2017) European Perceptions of Climate Change (EPCC): topline findings of a survey conducted in four European countries in 2016. Project: EPCC-European Perceptions of Climate Change and Energy Preferences: http://orca.cf.ac.uk/98660/7/EPCC.pdf

Štreimikienė D (2015) Assessment of reasonably achievable GHG emission reduction target in Lithuanian households. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 52:460–467

Tabi A (2013) Does pro-environmental behaviour affect carbon emissions? Energy Policy 63:972–981

Tranter B (2013) The great divide: political candidate and voter polarisation over global warming in Australia. Aust J Politics Hist 59(3):397–413

UK Programme (2019) Global Alliance for Buildings and Construction, International Energy Agency and the United Nations Environment Programme: 2019 global status report for buildings and construction: towards a zero-emission, efficient and resilient buildings and construction sector. http://inx.lv/Ei4A

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (2015) Paris Climate Change Conference – November 2015. https://unfccc.int/files/essential_background/convention/application/pdf/english_paris_agreement.pdf

Van Borgstede C, Johnsson F, Andersson M (2013) Public attitudes to climate change and carbon mitigation – Implications for energy associated behaviours. Energy Policy 57:182–193

Van der Linden S, Leiserowitz A, Rosenhthal S, Maibach E (2017) Inoculating the Public against Misinformation about Climate Change. Science 358(6367):1141–1142

Visschers VHM (2017) Public perception of uncertainties within climate change science. Risk Anal 38(1):43–55

Wakiyama T, Kuramochi T (2017) Scenario analysis of energy saving and CO2 emissions reduction potentials to ratchet up Japanese mitigation target in 2030 in the residential sector. Energy Policy 103:1–15

Wang B, Wang Q, Wei MY, Li PZ (2018) Role of renewable energy in China’s energy security and climate change mitigation: an index decomposition analysis. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 90:187–194

Weber EU, Stern PC (2011) Public understanding of climate change in the United States. Am Psychologist 66(4):315–328

Wei J, Chen H, Long R (2016) Is ecological personality always consistent with low-carbon behavioral intention of urban residents? Energy Policy 98:343–352

Wheeler S, Zuo A, Bjornlund H (2013) Farmers’ climate change beliefs and adaptation strategies for a water scarce future in Australia. Glob Environ Change 23:537–547

Whitmarsh L (2011) Scepticism and uncertainty about climate change: dimensions, determinants and change over time. Glob Environ Change 21:690–700

Whitmarsh L, Capstick S (2018) Perceptions of climate change. In: Clayton S, Manning C (Eds), Psychology and climate change: Human perceptions, impacts, and responses: p. 13–33. Netherlands, Amsterdam: Elsevier Academic Press

Williamson K, Satre-Meloy A, Velasco K, Green K (2018) Climate Change Needs Behavior Change: Making the Case For Behavioral Solutions to Reduce Global Warming. Arlington, VA: Rare

Zaval L, Keenan E, Johnson JE (2014) How warm days increase belief in global warming. Nat Clim Change 4(2):143–147

Zsoka A, Szerenyi Z, Szechy A, Kocsis T (2013) Greening due to environmental education? Environmental knowledge, attitudes, consumer behavior and everyday pro-environmental activities of Hungarian high school and university students. J Clean Prod 48:126–138

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A. Mean Score and Standard Deviation of the Respondents' Climate Change Concern, Responsibility Assumption and Climate-friendly Behaviours

Climate change concern | Responsibility | You try to reduce your waste and you regularly separate it for recycling | When buying a new household appliance, you choose it mainly because it was more energy efficient than other models | You regularly use environmentally friendly alternatives to using your private car such as walking, biking, taking public transport or car-sharing | You have insulated your home better to reduce your energy consumption | You have switched to an energy supplier which offers a greater share of energy from renewable sources than your previous one | You have bought a new car and its low-fuel consumption was an important factor in your choice | You have bought a low-energy home | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

2011 | 7.39 | 2.164 | 0.20 | 0.379 | 0.64 | 0.481 | 0.31 | 0.463 | 0.27 | 0.442 | 0.19 | 0.390 | 0.06 | 0.246 | 0.10 | 0.295 | 0.03 | 0.162 |

2013 | 7.22 | 2.161 | 0.23 | 0.424 | 0.64 | 0.479 | 0.33 | 0.472 | 0.27 | 0.443 | 0.22 | 0.416 | 0.07 | 0.253 | 0.10 | 0.306 | 0.03 | 0.174 |

2015 | 7.24 | 2.119 | 0.21 | 0.405 | 0.72 | 0.451 | 0.43 | 0.495 | 0.36 | 0.480 | 0.25 | 0.433 | 0.08 | 0.276 | 0.13 | 0.340 | 0.05 | 0.207 |

2017 | 7.66 | 2.150 | 0.24 | 0.429 | 0.69 | 0.461 | 0.39 | 0.488 | 0.26 | 0.439 | 0.21 | 0.404 | 0.07 | 0.260 | 0.10 | 0.300 | 0.03 | 0.172 |

2019 | 7.86 | 2.070 | 0.35 | 0.478 | 0.73 | 0.442 | 0.50 | 0.500 | 0.35 | 0.478 | 0.26 | 0.440 | 0.10 | 0.304 | 0.12 | 0.327 | 0.05 | 0.210 |

Appendix B. Climate-friendly Behaviour in Each EU Country in the Period of 2015–2019

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jakučionytė-Skodienė, M., Liobikienė, G. The Changes in Climate Change Concern, Responsibility Assumption and Impact on Climate-friendly Behaviour in EU from the Paris Agreement Until 2019. Environmental Management 69, 1–16 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-021-01574-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-021-01574-8