Abstract

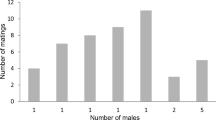

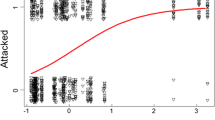

Theory suggests that males should adjust courtship in response to a variety of factors, including female quality, the risk of male-male competition, and often in spiders, the risk of sexual cannibalism. Male black widow spiders demonstrate a behavior during courtship whereby they tear down and bundle a female’s web in addition to providing other vibratory and contact sexual signals. This web reduction has been hypothesized to play a role in all three factors (sexual signaling, competition reduction, and cannibalism reduction), but rarely are these tested together. Here, we test these hypotheses by conducting mating trials using the western black widow (Latrodectus hesperus) and measuring both male and female quality and behavior. Our results indicate that amount of web reduction is best predicted by female aggression, and not aspects of either male or female quality (e.g., body mass), or by the potential for the web to attract other males (e.g., web mass). Yet, actual mating success was best predicted by the proportion of web reduced. Furthermore, there was no consistent among-individual variation in either reduction behavior or male success, indicating that all variation in both measures was due to plasticity and/or other unaccounted-for male or female traits. Collectively, we conclude that the primary function of web reduction behavior is to reduce female aggression and thus the risk of sexual cannibalism, and that any other functions such as signaling and reducing male-male competition have relatively lower importance.

Significance statement

Male widow spiders must account for female aggression, quality, and male-male competition when courting females. During courtship, males will reduce a female’s web by tearing it down and bundling the silk, which may aid in all three of these issues. Our results demonstrate that males reduce the webs of aggressive females more, and less so to potentially reduce competition from other males or in response to female quality. Ultimate mating success was dictated by how much a male reduced the web of a given female. Finally, males showed no among-individual variation in reduction behavior, indicating that the extensive variation in this behavior is due solely to plasticity in response to the female.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data and the associated R script will be uploaded to DRYAD upon acceptance of this manuscript.

Change history

25 January 2019

This article was originally inadvertently published in 2019, in Vol. 73, Issue 1, citation ID 1. It has now been reassigned and republished in 2019, in Vol. 73, Issue 2, citation ID 1.

References

Akaike H (1987) Factor analysis and AIC. Psychometrika 52:317–332

Anava A, Lubin Y (1993) Presence of gender cues in the web of a widow spider, Latrodectus revivensis, and a description of courtship behaviour. Bull Br Arachnol Soc 9:119–122

Andersson M, Simmons LW (2006) Sexual selection and mate choice. Trends Ecol Evol 21:296–302

Andrade MC (2003) Risky mate search and male self-sacrifice in redback spiders. Behav Ecol 14:531–538

Arnqvist G, Henriksson S (1997) Sexual cannibalism in the fishing spider and a model for the evolution of sexual cannibalism based on genetic constraints. Evol Ecol 11:255–273

Avigliano E, Scardamaglia RC, Gabelli FM, Pompilio L (2016) Males choose to keep their heads: preference for lower risk females in a praying mantid. Behav Process 129:80–85

Bartoń K (2013) MuMIn: multi-model inference. R package version 1.9. The Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN), Vienna, p 13

Baruffaldi L, Andrade MC (2015) Contact pheromones mediate male preference in black widow spiders: avoidance of hungry sexual cannibals? Anim Behav 102:25–32

Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S (2013) lme4: Linear mixed-effects models using Eigen and S4. R package version 1

Berning AW, Gadd RD, Sweeney K, MacDonald L, Eng RY, Hess ZL, Pruitt JN (2012) Sexual cannibalism is associated with female behavioural type, hunger state and increased hatching success. Anim Behav 84:715–721

Blackledge TA, Zevenbergen JM (2007) Condition-dependent spider web architecture in the western black widow. Anim Behav 73:855–864

Bonduriansky R (2001) The evolution of male mate choice in insects: a synthesis of ideas and evidence. Biol Rev 76:305–339

Breene RG, Sweet MH (1985) Evidence of insemination of multiple females by the male black widow spider, Latrodectus mactans (Araneae, Theridiidae). J Arachnol:331–335

Burnham K, Anderson D (2002) Model selection and multimodel inference: a practical information-theoretic approach. Springer

Byrne PG, Rice WR (2006) Evidence for adaptive male mate choice in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster. Proc R Soc B 273:917–922

DeWitt TJ, Sih A, Wilson DS (1998) Costs and limits of phenotypic plasticity. Trends Ecol Evol 13:77–81

Dingemanse NJ, Kazem AJ, Réale D, Wright J (2010) Behavioural reaction norms: animal personality meets individual plasticity. Trends Ecol Evol 25:81–89

DiRienzo N, Aonuma H (2017) Individual differences are consistent across changes in mating status and mediated by biogenic amines. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 71:118

DiRienzo N, Aonuma H (2018) Plasticity in extended phenotype increases offspring defence despite individual variation in web structure and behaviour. Anim Behav 138:9–17

DiRienzo N, Montiglio P-O (2016a) Linking consistent individual differences in web structure and behavior in black widow spiders. Behav Ecol 27:1424–1431

DiRienzo N, Montiglio PO (2016b) The contribution of developmental experience vs. condition to life history, trait variation and individual differences. J Anim Ecol 85:915–926

DiRienzo N, Bradley CT, Smith CA, Dornhaus A (2018) Data From: Bringing down the house: male widow spiders reduce the webs of aggressive females more. Behav Ecol Socibiol. https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.tp7637c

Edward DA, Chapman T (2011) The evolution and significance of male mate choice. Trends Ecol Evol 26:647–654

Elgar MA (1991) Sexual cannibalism, size dimorphism, and courtship behavior in orb-weaving spiders (Araneidae). Evolution 45:444–448

Emlen ST, Oring LW (1977) Ecology, sexual selection, and evolution of mating systems. Science 197:215–223

Gaskett AC, Herberstein ME, Downes BJ, Elgar MA (2004) Changes in male mate choice in a sexually cannibalistic orb-web spider (Araneae: Araneidae). Behaviour 141:1197–1210

Harari AR, Ziv M, Lubin Y (2009) Conflict or cooperation in the courtship display of the white widow spider. J Arachnol 37:254–260

Harrison XA (2014) Using observation-level random effects to model overdispersion in count data in ecology and evolution. PeerJ 2:e616

Head G (1995) Selection on fecundity and variation in the degree of sexual size dimorphism among spider species (class Araneae). Evolution 49:776–781

Herberstein ME, Wignall AE, Hebets E, Schneider JM (2014) Dangerous mating systems: signal complexity, signal content and neural capacity in spiders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 46:509–518

Johnson JC, Sih A (2005) Precopulatory sexual cannibalism in fishing spiders (Dolomedes triton): a role for behavioral syndromes. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 58:390–396

Johnson JC, Trubl P, Blackmore V, Miles L (2011) Male black widows court well-fed females more than starved females: silken cues indicate sexual cannibalism risk. Anim Behav 82:383–390

Kasumovic MM, Andrade MC (2004) Discrimination of airborne pheromones by mate-searching male western black widow spiders (Latrodectus hesperus): species-and population-specific responses. Can J Zool 82:1027–1034

Landolfa M, Barth F (1996) Vibrations in the orb web of the spider Nephila clavipes: cues for discrimination and orientation. J Comp Physiol A 179:493–508

Lubin YD (1986) Courtship and alternative mating tactics in a social spider. J Arachnol:239–257

MacLeod EC, Andrade MC (2014) Strong, convergent male mate choice along two preference axes in field populations of black widow spiders. Anim Behav 89:163–169

Møller AP, Alatalo RV (1999) Good-genes effects in sexual selection. Proc R Soc B 266:85–91

Montiglio P-O, DiRienzo N (2016) There’s no place like home: the contribution of direct and extended phenotypes on the expression of spider aggressiveness. Behav Ecol:arw094

Nakagawa S, Schielzeth H (2010) Repeatability for Gaussian and non-Gaussian data: a practical guide for biologists. Biol Rev 85:935–956

Nakagawa S, Schielzeth H (2013) A general and simple method for obtaining R2 from generalized linear mixed-effects models. Methods Ecol Evol 4:133–142

Persons MH, Uetz GW (2005) Sexual cannibalism and mate choice decisions in wolf spiders: influence of male size and secondary sexual characters. Anim Behav 69:83–94

R Core Team (2015) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. In. Available from CRAN sites

Réale D, Reader SM, Sol D, McDougall PT, Dingemanse NJ (2007) Integrating animal temperament within ecology and evolution. Biol Rev 82:291–318

Richards SA (2005) Testing ecological theory using the information-theoretic approach: examples and cautionary results. Ecology 86:2805–2814

Ross K, Smith RL (1979) Aspects of the courtship behavior of the black widow spider, Latrodectus hesperus (Araneae: Theridiidae), with evidence for the existence of a contact sex pheromone. J Arachnol:69–77

Rovner JS (1968) Territoriality in the sheet-web spider Linyphia triangularis (Clerck)(Araneae, Linyphiidae). Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie 25:232–242

Rubenstein DI (1987) Alternative reproductive tactics in the spider Meta segmentata. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 20:229–237

Schielzeth H, Nakagawa S (2011) rptR: repeatability for Gaussian and non-Gaussian data. R package version 0.6 404:r36

Scott C, Vibert S, Gries G (2012) Evidence that web reduction by western black widow males functions in sexual communication. Can Entomol 144:672–678

Scott C, Kirk D, McCann S, Gries G (2015) Web reduction by courting male black widows renders pheromone-emitting females’ webs less attractive to rival males. Anim Behav 107:71–78

Scott C, Gerak C, McCann S, Gries G (2017) The role of silk in courtship and chemical communication of the false widow spider, Steatoda grossa (Araneae: Theridiidae). Ethology:1–7

Sih A, Bell A, Johnson JC (2004) Behavioral syndromes: an ecological and evolutionary overview. Trends Ecol Evol 19:372–378

Van Helsdingen P (1965) Sexual behaviour of Lepthyphantes leprosus (Ohlert)(Araneida, Linyphiidae), with notes on the function of the genital organs. Zoologische Mededelingen 41:15–42

Vibert S, Scott C, Gries G (2014) A meal or a male: the ‘whispers’ of black widow males do not trigger a predatory response in females. Front Zool 11(1):4

Wagenmakers E-J, Farrell S (2004) AIC model selection using Akaike weights. Psychon Bull Rev 11:192–196

Watanabe T (2000) Web tuning of an orb-web spider, Octonoba sybotides, regulates prey-catching behaviour. Proc R Soc B 267:565–569

Watson PJ (1986) Transmission of a female sex pheromone thwarted by males in the spider Linyphia litigiosa (Linyphiidae). Science 233:219–221

Wise DH (1979) Effects of an experimental increase in prey abundance upon the reproductive rates of two orb-weaving spider species (Araneae: Araneidae). Oecologia 41:289–300

Zahavi A (1975) Mate selection—a selection for a handicap. J Theor Biol 53:205–214

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Cameron Jones for comments on an early version of this manuscript.

Funding

Funding was provided by a University of Arizona Postdoctoral Excellence in Research and Teaching Fellowship (NIH # 5K12GM000708-17) awarded to ND and by the NSF (grant no. IOS-1455983 to AD).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ND and AD designed the study. ND conducted the experiment and data processing in conjunction with CB and CS. ND conducted the statistical analysis, and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the final editing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Widow spiders are not subject to any ethical protocals in the United States.

Additional information

Communicated by J. Pruitt

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

DiRienzo, N., Bradley, C.T., Smith, C.A. et al. Bringing down the house: male widow spiders reduce the webs of aggressive females more. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 73, 1 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-018-2618-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-018-2618-z