Abstract

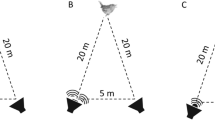

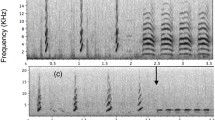

Many vertebrates use vocalizations to communicate about the presence of predators, and some encode information about predator type or behavior. A fast-approaching predator typically elicits a “flee alarm call,” prompting others to escape to safety. In a field experiment, we presented gliding models of a predatory bird to several species representing four families of passerine, including our model species, the zebra finch (Taeniopygia guttata). All families presented with the glider gave a distinct call on at least one occasion, apart from the zebra finch, for which no specific alarm call was recorded. Following on from this unexpected result, we conducted an experiment in which we exposed captive zebra finches to video of a looming raptor. Results of the captive study showed that birds responded to the looming raptor with escape behavior and responded to less threatening stimuli with orienting or startle behavior. Despite this anti-predator response, birds did not give any distinct alarm call, and the distance calls of both males and females did not differ in structure or rate of delivery after exposure to a stimulus. Zebra finches are one of the most studied birds in the world, are gregarious, and have a rich vocal repertoire, yet their alarm communication has not been investigated experimentally. Our results are consistent with the hypothesis that zebra finches lack a flee alarm call and appear not to signal about immediate danger through a change in calling rate.

Significance statement

Many animals emit alarm calls when faced with a threatening event in order to communicate with nearby group members. Threatening events can be simulated with models or by presenting a video of a looming stimulus on a screen. In separate studies, we presented gliding models and computer animations of a hawk to zebra finches, a bird species used in studies around the world, in order to test if they gave alarm calls to warn others of approaching danger. Although birds fled in response to the simulated predators, they did not emit a distinct alarm call. The birds also did not change their rate of calling or the acoustic structure of their distance calls. Surprisingly for a social and highly vocal species, the birds appear to lack alarm calls warning flockmates of immediate danger.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bach DR, Neuhoff JG, Perrig W, Seifritz E (2009) Looming sounds as warning signals: the function of motion cues. Int J Psychophysiol 74:28–33

Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S (2015) Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw 67:1–48

Bell MBV, Radford AN, Rose R, Wade HM, Ridley AR (2009) The value of constant surveillance in a risky environment. Proc R Soc Lond B 276:2997–3005

Blumstein DT, Armitage KB (1997) Alarm calling in yellow-bellied marmots: I. The meaning of situationally variable alarm calls. Anim Behav 53:143–171

Bradbury JW, Vehrencamp SL (2011) Principles of animal communication. Sinauer, Sunderland

Carlile PA, Peters RA, Evans CS (2006) Detection of a looming stimulus by the Jacky dragon: selective sensitivity to characteristics of an aerial predator. Anim Behav 72:553–562

Caro T (2005) Antipredator defenses in birds and mammals. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Charif RA, Waack AM, Strickman LM (2010) Raven Pro 1.4 user’s manual. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca

Curio E (1975) The functional organization of anti-predator behaviour in the pied flycatcher: a study of avian visual perception. Anim Behav 23:1–115

Dapper AL, Baugh AT, Ryan MJ (2011) The sounds of silence as an alarm cue in túngara frogs, Physalaemus pustulosus. Biotropica 73:380–385

Davies NB, Welbergen JA (2009) Social transmission of a host defense against cuckoo parasitism. Science 324:1318–1320

Fallow PM, Magrath RD (2010) Eavesdropping on other species: mutual interspecific understanding of urgency information in avian alarm calls. Anim Behav 79:411–417

Gill SA, Bierema AM-K (2013) On the meaning of alarm calls: a review of functional reference in avian alarm calling. Ethology 119:449–461

Giuliano C (2012) Do wild zebra finch (Taeniopygia guttata) respond to aerial alarm calls of sympatric heterospecifics? Honours thesis, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia

Goodale E, Kotagama SW (2005) Alarm calling in Sri Lankan mixed-species bird flocks. Auk 122:108–120

Goodale E, Kotagama SW (2008) Response to conspecific and heterospecific alarm calls in mixed-species bird flocks of a Sri Lankan rainforest. Behav Ecol 19:887–894

Goodale E, Beauchamp G, Magrath RD, Nieh JC, Ruxton GD (2010) Interspecific information transfer influences animal community structure. Trends Ecol Evol 25:354–361

Griesser M, Ekman J (2004) Nepotistic alarm calling in the Siberian jay, Perisoreus infaustus. Anim Behav 67:933–939

Griffin AS, Savani RS, Hausmanis K, Lefebvre L (2005) Mixed-species aggregations in birds: zenaida doves, Zenaida aurita, respond to the alarm calls of carib grackles, Quiscalus lugubris. Anim Behav 70:507–515

Griffith SC, Buchanan KL (2010) The zebra finch: the ultimate Australian supermodel. Emu 110:v–xii

Haff TM, Horn AG, Leonard ML, Magrath RD (2014) Conspicuous calling near cryptic nests: a review of hypotheses and a field study on white-browed scrubwrens. J Avian Biol 45:1–14

Higgins PJ, Peter JM (2002) Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic birds. Volume 6: pardalotes to shrike-thrushes. Oxford University Press, Melbourne

Higgins PJ, Peter JM, Steele WK (2001) Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic birds. Volume 5: tyrant-flycatchers to chats. Oxford University Press, Melbourne

Higgins PJ, Peter JM, Cowling SJ (2006) Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic birds. Volume 7: boatbill to starlings. Oxford University Press, Melbourne

Hollén LI, Radford AN (2009) The development of alarm call behaviour in mammals and birds. Anim Behav 78:791–800

Hollén LI, Bell MBV, Radford AN (2008) Cooperative sentinel calling? Foragers gain increased biomass intake. Curr Biol 18:576–579

Judge SJ, Rind FC (1997) The locust DCMD, a movement-detecting nurone tightly tuned to collision trajectories. J Exp Biol 200:2209–2216

Jurisevic MA, Sanderson KJ (1994a) Alarm vocalisations in Australian birds: convergent characteristics and phylogenetic differences. Emu 94:69–77

Jurisevic MA, Sanderson KJ (1994b) The vocal repertoires of six honeyeater (Meliphagidae) species from Adelaide, South Australia. Emu 94:141–148

Klump GM, Shalter MD (1984) Acoustic behaviour of birds and mammals in the predator context. Z Tierpsychol 66:189–226

Klump GM, Kretzschmar E, Curio E (1986) The hearing of an avian predator and its avian prey. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 18:317–323

Leavesley AJ, Magrath RD (2005) Communicating about danger: urgency alarm calling in a bird. Anim Behav 70:365–373

Lima SL (1995) Collective detection of predatory attack by social foragers: fraught with ambiguity? Anim Behav 50:1097–1108

Magrath RD, Pitcher BJ, Gardner JL (2007) A mutual understanding? Interspecific responses by birds to each other’s aerial alarm calls. Behav Ecol 18:944–951

Magrath RD, Haff TM, Fallow PM, Radford AN (2015) Eavesdropping on heterospecific alarm calls: from mechanisms to consequences. Biol Rev 90:560–586

Mainwaring MC, Griffith SC (2013) Looking after your partner: sentinel behaviour in a socially monogamous bird. PeerJ 1:e83

Manser MB (1999) Response of foraging group members to sentinel calls in suricates, Suricata suricatta. Proc R Soc Lond B 266:1013–1019

Manser MB (2001) The acoustic structure of suricates’ alarm calls varies with predator type and the level of urgency. Proc R Soc Lond B 268:2315–2324

Marchant S, Higgins PJ (1993) Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic birds. Volume 2: raptors to lapwings. Oxford University Press, Melbourne

Marler P (1955) Characteristics of some animal calls. Nature 176:6–8

Martínez AE, Zenil RT (2012) Foraging guild influences dependence on heterospecific alarm calls in Amazonian bird flocks. Behav Ecol 23:544–550

Maynard Smith J (1965) The evolution of alarm calls. Am Nat 99:59–63

McCowan LSC, Mariette MM, Griffith SC (2015) The size and composition of social groups in the wild zebra finch. Emu 115:191–198

McMillan GA, Gray JR (2012) A looming-sensitive pathway responds to changes in the trajectory of object motion. J Neurophysiol 108:1052–1068

Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D, R Development Core Team (2013) nlme: Linear and nonlinear mixed effects models. R package version 3.1–111, http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nlme

Pizzey G, Knight F (2012) The field guide to the birds of Australia. HarperCollins Publishers, Sydney

R Core Team (2013) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, https://www.R-project.org/

Schiff W (1965) Perception of impending collision: a study of visually directed avoidant behavior. Psychol Monogr 79:1–26

Schiff W, Caviness JA, Gibson JJ (1962) Persistent fear responses in rhesus monkeys to the optical stimulus of “looming”. Science 136:982–983

Sherman PW (1977) Nepotism and the evolution of alarm calls. Science 197:1246–1253

Sloan JL, Hare JF (2008) The more the scarier: adult Richardson’s ground squirrels (Spermophilus richardsonii) assess response urgency via the number of alarm signallers. Ethology 114:436–443

Sridhar H, Beauchamp G, Shanker K (2009) Why do birds participate in mixed-species foraging flocks? A large-scale synthesis. Anim Behav 78:337–347

Srinivasan U, Raza RH, Quader S (2010) The nuclear question: rethinking species importance in multi-species animal groups. J Anim Ecol 79:948–954

Sullivan K (1985) Selective alarm calling by downy woodpeckers in mixed-species flocks. Auk 102:184–187

Tchernichovski O, Nottebohm F, Ho CE, Pesaran B, Mitra PP (2000) A procedure for an automated measurement of song similarity. Anim Behav 59:1167–1176

Templeton CN, Greene E, Davis K (2005) Allometry of alarm calls: black-capped chickadees encode information about predator size. Science 308:1934–1937

Wang Y, Frost BJ (1992) Time to collision is signalled by neurons in the nucleus rotundus of pigeons. Nature 356:236–238

Wheatcroft D (2015) Repetition rate of calls used in multiple contexts communicates presence of predators to nestlings and adult birds. Anim Behav 103:35–44

Wilson DR, Evans CS (2008) Mating success increases alarm-calling effort in male fowl, Gallus gallus. Anim Behav 76:2029–2035

Woo KL, Rieucau G (2011) From dummies to animations: a review of computer-animated stimuli used in animal behavior studies. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 65:1671–1685

Zann RA (1996) The zebra finch: a synthesis of field and laboratory studies. Oxford University Press, New York

Zuberbühler K (2000) Referential labelling in Diana monkeys. Anim Behav 59:917–927

Zuberbühler K (2009) Survivor signals: the biology and psychology of animal alarm calling. Adv Stud Behav 40:277–322

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Juan Hernandez and Jon Salisbury for help with constructing the gliders, and Tom Chandler and Chandara Ung at Monash University for creating the animations. Assistance in the field was provided by Melissa Van De Wetering, Bridie Clarke, Heather Maginn, José Ramos, Jordan de Jong, Travis Dutka, Jemima Connell, Kristian Bones Enger, Shannan Courtenay, Lauren Grimes, Tom Handley, and Kathryn Lyons. Thanks to Nicola Khan for helping with husbandry of the finches and Angela Simms for assisting with video analysis. Thanks to our anonymous reviewers for providing valuable feedback on the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This research was supported by funding from La Trobe University. Field work was supported by a Holsworth Wildlife Research Endowment awarded to NEB.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed. All procedures performed in studies involving animals were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution or practice at which the studies were conducted. This article does not contain any studies with human participants by any of the authors. All experimental procedures were approved by La Trobe University’s Animal Ethics Committee (AEC protocol no. 12-39) and conducted under Victorian Government DELWP permit nos. 10007632 and 10007491 and NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service permit no. SL101447.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the La Trobe University FigShare repository and have the following DOI: 10.4225/22/592e4f968fe8d

Additional information

Communicated by P. A. Bednekoff

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Butler, N.E., Magrath, R.D. & Peters, R.A. Lack of alarm calls in a gregarious bird: models and videos of predators prompt alarm responses but no alarm calls by zebra finches. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 71, 113 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-017-2343-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-017-2343-z