Abstract

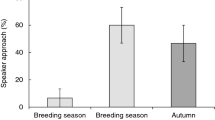

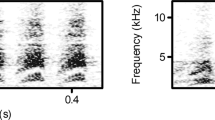

Black-capped chickadees Poecile atricapillus alter the number of D notes of their chick-a-dee call to reflect urgency and threat. Here, I tested whether heterospecific responses of an allopatric species to these mobbing calls occur. Heterospecific chickadee mobbing calls and songs from North America were broadcast to European great tits (Parus major) and compared with conspecific mobbing calls. During conspecific mobbing playbacks, all great tits approached the speaker, during the heterospecific “chick-a-dee” playbacks, 63.3% individuals approached the speaker, while during the song playback, only 31.3% of the great tits approached the speaker. Minimum distances of great tits were lower during conspecific mobbing calls compared to allopatric chick-a-dee calls and to allopatric chickadee song. Also, minimum distances were lower when comparing allopatric chick-a-dee calls and chickadee song. Great tits approached the speaker on average down to (mean ± SE) 20.0 ± 1.8 m during playbacks of 1–4 D elements, to 17.7 ± 2.0 m during playbacks of 5–7 D elements and down to 11.5 ± 2.0 m during playbacks of 8–11 D elements. The number of D notes was inversely related to minimum distance. Thus, the urgency message encoded in the D notes was perceived also by an allopatric but phylogenetically related European species, suggesting that the heterospecific response is possibly phylogenetically conserved.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Baker MC, Becker AM (2002) Mobbing calls of black-capped chickadees: effects of urgency on call production. Wilson Bull 114:510–516

Barrera JP, Chong L, Judy KN, Blumstein DT (2011) Reliability of public information: predators provide more information about risk than conspecifics. Anim Behav 81:779–787

Bartmess-LeVasseur J, Branch CL, Browning SA, Owens JL, Freeberg TM (2010) Predator stimuli and calling behavior of Carolina chickadees (Poecile carolinensis), tufted titmice (Baeolophus bicolor), and white-breasted nuthatches (Sitta carolinensis). Behav Ecol Sociobiol 64:1187–1198

Blumstein DT, Armitage KB (1997) Alarm calling in yellow-bellied marmots: I. The meaning of situationally variable alarm calls. Anim Behav 53:143–171

Caro T (2005) Anti-predator defence in mammals and birds. Chicago University Press, Chicago

Charrier I, Sturdy CB (2005) Call-based species recognition in black-capped chickadees. Behav Process 70:271–281

Courter JR, Ritchison G (2010) Alarm calls of tufted titmice convey information about predator size and threat. Behav Ecol 21:936–942

Curio E, Ernst U, Vieth W (1978) The adaptive significance of avian mobbing. II. Cultural transmission of enemy recognition in blackbirds: effectiveness and some constraints. Z Tierpsychol 48:184–202

Dabelsteen T (2005) Public, private or anonymous? Facilitating and countering eavesdropping. In: McGregor PK (ed) Animal Communication Networks. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 38–62

de Kort SR, ten Cate C (2001) Response to interspecific vocalizations is affected by the degree of phylogenetic relatedness in Streptopelia doves. Anim Behav 61:239–247

Fallow PM, Magrath RD (2010) Eavesdropping on other species: mutual interspecific understanding of urgency information in avian alarm calls. Anim Behav 79:411–417

Fallow PM, Gardner JL, Magrath RD (2011) Sound familiar? Acoustic similarity provokes responses to unfamiliar heterospecific alarm calls. Behav Ecol 22:401–410

Fichtel C (2004) Reciprocal recognition of sifaka (Propithecus verreauxi verreauxi) and redfronted lemur (Eulemur fulvus rufus) alarm calls. Anim Cogn 7:45–52

Fichtel C, Hammerschmidt K (2002) Responses of red-fronted lemurs to experimentally modified alarm calls: evidence for urgency-based changes in call structure. Ethology 108:763–777

Ficken MS, Ficken RW, Witkin SR (1978) Vocal repertoire of the black-capped chickadee. Auk 95:34–48

Ficken MS, Popp J (1996) A comparative analysis of passerine mobbing calls. Auk 113:370–380

Flasskamp A (1994) The adaptive significance of avian mobbing. V. An experimental test of the ‘move on’ hypothesis. Ethology 96:322–333

Forsman JT, Mönkkönen M (2001) Responses by breeding birds to heterospecific song and mobbing call playbacks under varying predation risk. Anim Behav 62:1067–1073

Frankenberg E (1981) The adaptive significance of avian mobbing. IV. “Alerting others” and “perception advertisement” in blackbirds facing an owl. Z Tierpsychol 55:97–118

Goodale E, Beauchamp G, Magrath RD, Nieh JC, Ruxton GD (2010) Interspecific information transfer influences animal community structure. Trends Ecol Evol 25:354–361

Hauser MD (1988) How infant vervet monkeys learn to recognize starling alarm calls. Behaviour 105:187–201

Hauser MD, Wrangham RW (1990) Recognition of predator and competitor calls in nonhuman primates and birds: a preliminary report. Ethology 86:116–130

Hinde RA (1952) The behaviour of the great tit (Parus major) and some other related species. Behaviour Suppl 2:1–201

Hölzinger J (1997) Die Vögel Baden-Württembergs. Singvögel 2. Ulmer. Stuttgart.

Hurd CR (1996) Interspecific attraction to the mobbing calls of black-capped chickadees (Parus atricapillus). Behav Ecol Sociobiol 38:287–292

Johnson FR, McNaughton EJ, Shelley CD, Blumstein DT (2003) Mechanisms of heterospecific recognition in avian mobbing calls. Aust J Zool 51:577–585

Kitchen DM, Bergman TJ, Cheney DL, Nicholson JR, Seyfarth RM (2010) Comparing responses of four ungulate species to playbacks of baboon alarm calls. Anim Cogn 13:861–870

Krama T, Krams I, Igaune K (2008) Effects of cover on loud trill-call and soft seet-call use in the crested tit, Parus cristatus. Ethology 114:656–661

Krams I (2000) Long-call use in dominance-structured crested tit Parus cristatus winter groups. J Avian Biol 31:15–19

Krams I, Krama T (2002) Interspecific reciprocity explains mobbing behaviour of the breeding chaffinches, Fringilla coelebs. Proc Biol Sci 269:2345–2350

Langham GM, Contreras TA, Sieving KE (2006) Why pishing works: titmouse (Paridae) scolds elicit a generalized response in bird communities. Ecoscience 13:485–496

Lea AJ, Barrera JP, Tom LM, Blumstein DT (2008) Heterospecific eavesdropping in a non-social bird. Behav Ecol 19:1041–1046

Magrath RD, Pitcher BJ, Gardner JL (2007) A mutual understanding? Interspecific responses by birds to each other’s aerial alarm calls. Behav Ecol 18:944–951

Magrath RD, Pitcher BJ, Gardner JL (2009a) Recognition of other species’ aerial alarm calls: speaking the same language or learning another? Proc Biol Sci 276:769–774

Magrath RD, Pitcher BJ, Gardner JL (2009b) An avian eavesdropping network: alarm signal reliability and heterospecific response. Behav Ecol 20:745–752

Mahurin EJ, Freeberg TM (2009) Chick-a-dee call variation in Carolina chickadees and recruiting flockmates to food. Behav Ecol 20:111–116

Manser MB (2001) The acoustic structure of suricates’ alarm calls varies with predator type and the level of response urgency. Proc Biol Sci 268:2485–2491

Manser MB, Bell MB, Fletcher LB (2001) The information that receivers extract from alarm calls in suricates. Proc Biol Sci 268:2315–2324

Matessi G, Matos RJ, Dabelsteen T (2008) Communication in social networks of territorial animals: networking at different levels in birds and other systems. In d’Ettorre P, Hughes DP Sociobiology of communication—an interdisciplinary perspective. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 33–53

McGregor PK (2005) Animal Communication Networks. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Müller CA, Manser MB (2008) The information banded mongooses extract from heterospecific alarms. Anim Behav 75:897–904

Nocera JJ, Taylor PD, Ratcliffe LM (2009) Inspection of mob-calls as sources of predator information: response of migrant and resident birds in the Neotropics. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 62:1769–1777

Nuechterlein GL (1981) ‘Information parasitism’ in mixed colonies of Western Grebes and Forster’s Terns. Anim Behav 29:985–989

Oda R, Matasaka N (1996) Interspecific responses of ringtailed lemurs to playback of antipredator alarm calls given by Verreaux’s sifakas. Ethology 102:441–452

Ostreiher R (2003) Is mobbing altruistic or selfish behaviour? Anim Behav 66:145–149

Pavey CR, Smyth AK (1998) Effects of avian mobbing on roost use and diet of powerful owls, Ninox strenua. Anim Behav 55:313–318

Pettifor RA (1990) The effects of avian mobbing on a potential predator, the European kestrel, Falco tinnunculus. Anim Behav 39:821–827

Rainey HJ, Zuberbühler K, Slater PJB (2004a) Hornbills can distinguish between primate alarm calls. Proc Biol Sci 271:755–759

Rainey HJ, Zuberbühler K, Slater PJB (2004b) The responses of black-casqued hornbills to predator vocalisations and primate alarm calls. Behaviour 141:1263–1277

Ramakrishnan U, Coss RG (2000) Recognition of heterospecific alarm vocalizations by bonnet macaques (Macaca radiata). J Comp Psych 114:3–12

Randler C (2006) Red squirrels (Sciurus vulgaris) respond to alarm calls of Eurasian jays (Garrulus glandarius). Ethology 112:411–416

Randler C, Förschler MI (2011) Heterospecifics do not respond to subtle differences in chaffinch mobbing calls—message is encoded in number of elements. Anim Behav 82:725–730

Ratcliffe L, Weisman RG (1985) Frequency shift in the fee bee song of the black-capped chickadee. Condor 87:555–556

Roux AL, Cherry MI, Manser MB (2009) The vocal repertoire in a solitary foraging carnivore, Cynictis penicillata, may reflect facultative sociality. Naturwissenschaften 96:575–584

Russ JM, Jones G, Mackie IJ, Racey PA (2004) Interspecific responses to distress calls in bats (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae): a function for convergence in call design? Anim Behav 67:1005–1014

Schulze A (2003) Die Vogelstimmen Europas, Nordafrikas und Vorderasiens. Germering, Edition Ample

Seyfarth RM, Cheney DL (1990) The assessment by vervet monkeys of their own and another species’ alarm calls. Anim Behav 40:754–764

Shriner WM (1999) Antipredator responses to a previously neutral sound by free-living adult golden-mantled ground squirrels, Spermophilus lateralis (Sciuridae). Ethology 105:747–757

Sieving KE, Hetrick SA, Avery ML (2010) The versatility of graded acoustic measures in classification of predation threats by the tufted titmouse Baeolophus bicolor: exploring a mixed framework for threat communication. Oikos 119:264–276

Soard CM, Ritchison G (2009) ‘Chick-a-dee’ calls of Carolina chickadees convey information about degree of threat posed by avian predators. Anim Behav 78:1447–1453

Sullivan K (1984) Information exploitation by downy woodpeckers in mixed-species flocks. Behaviour 91:294–311

Templeton CN, Greene E (2007) Nuthatches eavesdrop on variations in heterospecific chickadee mobbing alarm calls. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:5479–5482

Templeton CN, Greene E, Davis K (2005) Allometry of alarm calls: black-capped chickadees encode information about predator size. Science 308:1934–1937

Theis KR, Greene KM, Benson-Amram SR, Holekamp KE (2007) Sources of variation in the long-distance vocalizations of spotted hyenas. Behaviour 144:557–584

Turcotte Y, Desrochers A (2002) Playback of mobbing calls of black-capped chickadees help estimate the abundance of forest birds in winter. J Field Ornithol 73:303–307

Vitousek MN, Adelman JS, Gregory NC, St Clair JJH (2007) Heterospecific alarm call recognition in a non-vocal reptile. Biol Lett 3:632–634

Wilson DR, Mennill DJ (2011) Duty cycle, not signal structure, explains conspecific and heterospecific responses to the calls of black-capped Chickadees (Poecile atricapillus). Behav Ecol 22:784–790

Zuberbühler K (2000) Interspecies semantic communication in two forest primates. Proc Biol Sci 267:713–718

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Indrikis Krams and an anonymous reviewer for their helpful comments that improved the manuscript.

Ethical standards

The experiments comply with the current laws of Germany.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by H. Brumm

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Randler, C. A possible phylogenetically conserved urgency response of great tits (Parus major) towards allopatric mobbing calls. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 66, 675–681 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-011-1315-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-011-1315-y