Abstract

Background

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) blocking inhibitory immune pathways (e.g., programmed cell death protein-1/-ligand1 [PD-1/PD-L1]) have revolutionized cancer therapy for numerous malignancies. There have been an increasing number of cases of active tuberculosis (TB) reported in association with ICI use, and recent data suggest alterations in immune responses in TB by ICI. The aim of this study was to characterize the frequency of latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) and active TB in a large cohort of ICI-treated patients in a low TB incidence area.

Methods

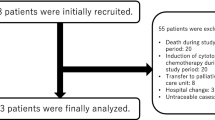

We conducted a retrospective review of all ICI-treated patients tested for TB between January, 1997 and August, 2018. Data extracted included patient demographics, TB risk factors, latent/active TB diagnosis and treatment, tumor type, ICI used, immunosuppressive medications, and mortality related to TB.

Results

We identified 1844 ICI-treated patients, including 30 abnormal TB test results. Two patients were diagnosed with active TB, both prior to starting ICI therapy. One patient was treated for TB prior to starting ICI and the other patient was successfully treated concurrently. Seven patients were diagnosed with LTBI and none developed active TB. Twenty patients had indeterminate interferon gamma release assays (IGRA).

Conclusion

Despite recent reports of TB in patients taking ICI, we found no patients developing TB during ICI therapy in our large retrospective cohort of ICI-treated cancer patients in a non-endemic TB area. The high rate of indeterminate IGRA results suggests the need for prospective research with better diagnostics to quantify the actual risk of TB in this patient population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- TB:

-

Active tuberculosis

- iAE:

-

Immune-related adverse event

- ICI:

-

Immune checkpoint inhibitor

- IGRA:

-

Interferon gamma release assay

- LTBI:

-

Latent tuberculosis infection

- Mtb:

-

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- PD-1:

-

Programmed cell death protein-1

- PD-L1:

-

Programmed death ligand 1

- TST:

-

Tuberculin skin test

References

Sharpe AH, Pauken KE (2018) The diverse functions of the PD1 inhibitory pathway. Nat Rev Immunol 18(3):153–167

Okazaki T, Honjo T (2006) The PD-1-PD-L pathway in immunological tolerance. Trends Immunol 27(4):195–201

Socinski MA et al (2018) Atezolizumab for first-line treatment of metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC. N Engl J Med 378(24):2288–2301

Forde PM et al (2018) Neoadjuvant PD-1 blockade in resectable lung cancer. N Engl J Med 378(21):1976–1986

Sanlorenzo M et al (2014) Melanoma immunotherapy. Cancer Biol Ther 15(6):665–674

Motzer RJ et al (2018) Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 378(14):1277–1290

Champiat S et al (2016) Management of immune checkpoint blockade dysimmune toxicities: a collaborative position paper. Ann Oncol 27(4):559–574

Genova C et al (2017) Releasing the brake: safety profile of immune check-point inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer. Expert Opin Drug Saf 16(5):573–585

Del Castillo M et al (2016) The spectrum of serious infections among patients receiving immune checkpoint blockade for the treatment of melanoma. Clin Infect Dis 63(11):1490–1493

Wykes MN, Lewin SR (2018) Immune checkpoint blockade in infectious diseases. Nat Rev Immunol 18(2):91–104

Liang SC et al (2006) PD-L1 and PD-L2 have distinct roles in regulating host immunity to cutaneous leishmaniasis. Eur J Immunol 36(1):58–64

He W et al (2018) Activated pulmonary tuberculosis in a patient with melanoma during PD-1 inhibition: a case report. Onco Targets Ther 11:7423–7427

Anastasopoulou A et al (2019) Reactivation of tuberculosis in cancer patients following administration of immune checkpoint inhibitors: current evidence and clinical practice recommendations. J Immunother Cancer 7(1):239

Chu YC et al (2017) Pericardial tamponade caused by a hypersensitivity response to tuberculosis reactivation after anti-PD-1 treatment in a patient with advanced pulmonary adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol 12(8):e111–e114

Fujita K, Terashima T, Mio T (2016) Anti-PD1 antibody treatment and the development of acute pulmonary tuberculosis. J Thorac Oncol 11(12):2238–2240

Lee JJ, Chan A, Tang T (2016) Tuberculosis reactivation in a patient receiving anti-programmed death-1 (PD-1) inhibitor for relapsed Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Acta Oncol 55(4):519–520

Picchi H et al (2018) Infectious complications associated with the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors in oncology: reactivation of tuberculosis after anti PD-1 treatment. Clin Microbiol Infect 24(3):216–218

Elkington PT et al (2018) Implications of tuberculosis reactivation after immune checkpoint inhibition. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 198:1451–1453

Barber DL et al (2019) Tuberculosis following PD-1 blockade for cancer immunotherapy. Sci Transl Med 11(475):2019

Jensen KH et al (2018) Development of pulmonary tuberculosis following treatment with anti-PD-1 for non-small cell lung cancer. Acta Oncol 57(8):1127–1128

Takata S et al (2019) Paradoxical response in a patient with non-small cell lung cancer who received nivolumab followed by anti-Mycobacterium tuberculosis agents. J Infect Chemother 25(1):54–58

Tsai CC et al (2019) Re-activation of pulmonary tuberculosis during anti-programmed death-1 (PD-1) treatment. QJM 112(1):41–42

van Eeden R et al (2019) Tuberculosis infection in a patient treated with nivolumab for non-small cell lung cancer: case report and literature review. Front Oncol 9:659

Song JS, Jeffery CC (2020) Laryngeal tuberculosis in a patient on avelumab for metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Immunother 43(7):222–223

Kato Y et al (2020) Reactivation of TB during administration of durvalumab after chemoradiotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer: a case report. Immunotherapy 12(6):373–378

Inthasot V et al (2020) Severe pulmonary infections complicating nivolumab treatment for lung cancer: a report of two cases. Acta Clin Belg 75(4):308–310

Anand K et al (2020) Mycobacterial infections due to PD-1 and PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitors. ESMO Open 5(4):e000866

Tezera LB et al (2020) Anti-PD-1 immunotherapy leads to tuberculosis reactivation via dysregulation of TNF-alpha. Elife 9:52668

Kauffman KD et al (2020) PD-1 blockade exacerbates Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in rhesus macaques. bioRxiv 18:91

Reungwetwattana T, Adjei AA (2016) Anti-PD-1 antibody treatment and the development of acute pulmonary tuberculosis. J Thorac Oncol 11(12):2048–2050

Health MDo. Tuberculosis, 2018. 2019. https://www.health.state.mn.us/diseases/reportable/dcn/sum18/tb.html

University M. The Online TST/IGRA Interpretor Version 3.0. http://www.tstin3d.com/en/calc.html

Santin M, Munoz L, Rigau D (2012) Interferon-gamma release assays for the diagnosis of tuberculosis and tuberculosis infection in HIV-infected adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 7(3):e32482

Shahidi N et al (2012) Performance of interferon-gamma release assays in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 18(11):2034–2042

Green AM, Difazio R, Flynn JL (2013) IFN-gamma from CD4 T cells is essential for host survival and enhances CD8 T cell function during Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J Immunol 190(1):270–277

Suarez-Mendez R et al (2004) Adjuvant interferon gamma in patients with drug—resistant pulmonary tuberculosis: a pilot study. BMC Infect Dis 4:44

Dawson R et al (2009) Immunomodulation with recombinant interferon-gamma1b in pulmonary tuberculosis. PLoS ONE 4(9):e6984

Nikitina IY et al (2012) Mtb-specific CD27low CD4 T cells as markers of lung tissue destruction during pulmonary tuberculosis in humans. PLoS ONE 7(8):e43733

Lazar-Molnar E et al (2010) Programmed death-1 (PD-1)-deficient mice are extraordinarily sensitive to tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107(30):13402–13407

Barber DL et al (2011) CD4 T cells promote rather than control tuberculosis in the absence of PD-1-mediated inhibition. J Immunol 186(3):1598–1607

Sakai S et al (2016) CD4 T Cell-Derived IFN-gamma Plays a Minimal Role in Control of Pulmonary Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection and Must Be Actively Repressed by PD-1 to Prevent Lethal Disease. PLoS Pathog 12(5):e1005667

Tousif S et al (2011) T cells from Programmed Death-1 deficient mice respond poorly to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. PLoS ONE 6(5):e19864

Casadevall A, Pirofski LA (2003) The damage-response framework of microbial pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol 1(1):17–24

Lin PL et al (2016) PET CT identifies reactivation risk in cynomolgus macaques with latent M. tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog 12(7):e1005739

Im Y et al (2020) Development of tuberculosis in cancer patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors. Respir Med 161:105853

Fujita K et al (2020) Incidence of active tuberculosis in lung cancer patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors. Open Forum Infect Dis 7(5):ofaa126

Langan EA et al (2020) Immune checkpoint inhibitors and tuberculosis: an old disease in a new context. Lancet Oncol 21(1):e55–e65

Acknowledgements

Heidi Finnes, PharmD, RPh and Lisa Kottschade, APRN, CNP assisted in identifying patients treated with ICI at Mayo Clinic.

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

GRS has no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose. TP participated in Advisory Boards for AstraZeneca and Novocure, outside the scope of the submitted work. All fees were paid to Mayo Clinic. PE participated in a short-term advisory scientific board for DiaSorin Molecular, which was outside the scope of the submitted work. Honorarium was paid to Mayo Clinic. PE has also filed two patent applications related to immunodiagnostic laboratory methodologies for latent tuberculosis infection for intellectual property protection purposes. To date, there has been no income or royalties associated with those filed patent applications. Otherwise, PE does not have other conflicts of interest COI to disclose. This paper’s contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or Mayo Clinic. No other financial or material support for this work was provided to the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stroh, G., Peikert, T. & Escalante, P. Active and latent tuberculosis infections in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors in a non-endemic tuberculosis area. Cancer Immunol Immunother 70, 3105–3111 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00262-021-02905-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00262-021-02905-8