Abstract

Background

Anti-PD-(L)1 blocking agents can induce immune-related adverse events (irAEs), which can compromise treatment continuation. Since circulating leukocyte–platelet (PLT) complexes contribute to inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, we aimed to analyze the role of these complexes as predictors of irAEs in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients receiving anti-PD-(L)1.

Materials and methods

Twenty-six healthy donors (HD) and 87 consecutive advanced NSCLC patients treated with anti-PD-(L)1 were prospectively included. Percentages of circulating leukocyte–PLT complexes were analyzed by flow cytometry and compared between HD and NSCLC patients. The association of leukocyte–PLT complexes with the presence and severity of irAEs was analyzed.

Results

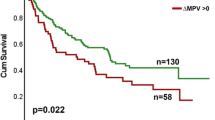

NSCLC patients had higher percentages of circulating leukocyte–PLT complexes. Higher percentages of monocytes with bound PLT (CD14 + PLT +) were observed in patients who received prior therapies while CD4 + T lymphocytes with bound PLT (CD4 + PLT +) correlated with platelets counts. The CD4 + PLT + high percentage group presented a higher rate of dermatological irAEs while the CD4 + PLT + low percentage group showed a higher rate of non-dermatological irAEs (p < 0.001). A lower frequency of grade ≥ 2 irAEs was observed in the CD4 + PLT + high percentage group (p < 0.05). Patients with CD4 + PLT + low and CD14 + PLT + high percentages presented a higher rate of grade ≥ 3 irAEs and predominantly developed non-dermatological irAEs (p < 0.01).

Conclusions

Our results suggest that circulating leukocyte–PLT complexes and the combination of CD4 + PLT + and CD14 + PLT + percentages can be used as a predictive biomarker of the development and severity of irAEs in advanced NSCLC patients receiving anti-PD-(L)1 agents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- ECOG:

-

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- FSC:

-

Forward scatter

- HD:

-

Healthy donors

- irAEs:

-

Immune-related adverse events

- IQR:

-

Interquartile ranges

- NSCLC:

-

Non-small cell lung cancer

- PD-1:

-

Programmed cell death-1 receptor

- PD-L1:

-

Programmed cell death ligand-1

- PLT:

-

Platelets

- PS:

-

Performance status

- SSC:

-

Side scatter

References

Naidoo J, Page DB, Wolchok JD (2014) Immune checkpoint blockade. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 28:585–600

Chen DS, Mellman I (2013) Oncology meets immunology: the cancer-immunity cycle. Immunity 39:1–10

Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P et al (2015) Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 373:123–135. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1504627

Rittmeyer A, Barlesi F, Waterkamp D et al (2017) Atezolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (OAK): a phase 3, open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 389:255–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32517-X

Paz-Ares L, Luft A, Vicente D et al (2018) Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy for squamous non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 379:2040–2051. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1810865

West H, McCleod M, Hussein M et al (2019) Atezolizumab in combination with carboplatin plus nab-paclitaxel chemotherapy compared with chemotherapy alone as first-line treatment for metastatic non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (IMpower130): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 20:924–937. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30167-6

Hellmann MD, Paz Ares L, Bernabe Caro R et al (2019) Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 381:2020–2031. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1910231

Postow MA, Sidlow R, Hellmann MD (2018) Immune-related adverse events associated with immune checkpoint blockade. N Engl J Med 378:158–168. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1703481

Weber JS, Hodi FS, Wolchok JD et al (2017) Safety profile of nivolumab monotherapy: a pooled analysis of patients with advanced melanoma. J Clin Oncol 35:785–792. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2015.66.1389

Haratani K, Hayashi H, Chiba Y et al (2018) Association of immune-related adverse events with nivolumab efficacy in non-small cell lung cancer. JAMA Oncol 4:374–378. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.2925

Toi Y, Sugawara S, Sugisaka J et al (2019) Profiling preexisting antibodies in patients treated with anti-PD-1 therapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. JAMA Oncol 5:376–383. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.5860

Curry JL, Tetzlaff MT, Nagarajan P et al (2017) Diverse types of dermatologic toxicities from immune checkpoint blockade therapy. J Cutan Pathol 44:158–176

Naidoo J, Wang X, Woo KM et al (2017) Pneumonitis in patients treated with anti-programmed death-1/programmed death ligand 1 therapy. J Clin Oncol 35:709–717. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.68.2005

Abu-Sbeih H, Ali FS, Luo W et al (2018) Importance of endoscopic and histological evaluation in the management of immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis. J Immunother Cancer. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40425-018-0411-1

Corsello SM, Barnabei A, Marchetti P et al (2013) Endocrine side effects induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 98:1361–1375. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2012-4075

Callahan MK, Yang A, Tandon S et al (2011) Evaluation of serum IL-17 levels during ipilimumab therapy: correlation with colitis. J Clin Oncol 29:2505–2505. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2011.29.15_suppl.2505

Stucci S, Palmirotta R, Passarelli A et al (2017) Immune-related adverse events during anticancer immunotherapy: pathogenesis and management. Oncol Lett 14:5671–5680

Kaehler KC, Piel S, Livingstone E et al (2010) Update on immunologic therapy with antiCTLA-4 antibodies in melanoma: Identification of clinical and biological response patterns, immune-related adverse events, and their management. Semin Oncol 37:485–498. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.seminoncol.2010.09.003

Dinkla S, van Cranenbroek B, van der Heijden WA et al (2016) Platelet microparticles inhibit IL-17 production by regulatory T cells through P-selectin. Blood 127:1976–1986. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2015-04-640300

McNicol A, Israels S (2008) Beyond hemostasis: the role of platelets in inflammation, malignancy and infection. Cardiovasc Hematol Disord Targets 8:99–117. https://doi.org/10.2174/187152908784533739

Zamora C, Canto E, Nieto JC et al (2013) Functional consequences of platelet binding to T lymphocytes in inflammation. J Leukoc Biol 94:521–529. https://doi.org/10.1189/jlb.0213074

Zamora C, Canto E, Nieto JC et al (2017) Binding of platelets to lymphocytes: a potential anti-inflammatory therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. J Immunol 198:3099–3108. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1601708

Li N, Ji Q, Hjemdahl P (2006) Platelet-lymphocyte conjugation differs between lymphocyte subpopulations. J Thromb Haemost 4:874–881. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01817.x

Zamora C, Canto E, Nieto JC et al (2018) Inverse association between circulating monocyte-platelet complexes and inflammation in ulcerative colitis patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis 24:818–828. https://doi.org/10.1093/ibd/izx106

Liu CY, Battaglia M, Lee SH et al (2005) Platelet factor 4 differentially modulates CD4 + CD25 + (Regulatory) versus CD4 + CD25 − (Nonregulatory) T cells. J Immunol 174:2680–2686. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2680

Rachidi S, Metelli A, Riesenberg B et al (2017) Platelets subvert T cell immunity against cancer via GARP-TGF axis. Sci Immunol. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciimmunol.aai7911

Elalamy I, Chakroun T, Gerotziafas GT et al (2008) Circulating platelet-leukocyte aggregates: a marker of microvascular injury in diabetic patients. Thromb Res 121:843–848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2007.07.016

Marques P, Collado A, Martinez-Hervás S et al (2019) Systemic inflammation in metabolic syndrome: increased platelet and leukocyte activation, and key role of CX3CL1/CX3CR1 and CCL2/CCR2 axes in arterial platelet-proinflammatory monocyte adhesion. J Clin Med 8:708. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8050708

Suzuki J, Hamada E, Shodai T et al (2013) Cytokine secretion from human monocytes potentiated by P-selectin-mediated cell adhesion. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 160:152–160. https://doi.org/10.1159/000339857

Weyrich AS, Elstad MR, McEver RP et al (1996) Activated platelets signal chemokine synthesis by human monocytes. J Clin Invest 97:1525–1534. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI118575

(2009) National Cancer Institute. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events. https://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/CTCAE_4.03/Archive/CTCAE_4.0_2009-05-29_QuickReference_8.5x11.pdf

Li N (2016) Platelets in cancer metastasis: to help the “villain” to do evil. Int J Cancer 138:2078–2087

Miyashita T, Tajima H, Makino I et al (2015) Metastasis-promoting role of extravasated platelet activation in tumor. J Surg Res 193:289–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2014.07.037

Labelle M, Begum S, Hynes RO (2011) Direct signaling between platelets and cancer cells induces an epithelial-mesenchymal-like transition and promotes metastasis. Cancer Cell 20:576–590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2011.09.009

Placke T, Kopp HG, Salih HR (2011) Modulation of natural killer cell anti-tumor reactivity by platelets. J Innate Immun 3:374–382

Togna GI, Togna AR, Franconi M, Caprino L (2000) Cisplatin triggers platelet activation. Thromb Res 99:503–509. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0049-3848(00)00294-2

Starossom SC, Veremeyko T, Yung AWY et al (2015) Platelets play differential role during the initiation and progression of autoimmune neuroinflammation. Circ Res 117:779–792. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306847

Li N (2008) Platelet-lymphocyte cross-talk. J Leukoc Biol 83:1069–1078. https://doi.org/10.1189/jlb.0907615

van Gils JM, Zwaginga JJ, Hordijk PL (2009) Molecular and functional interactions among monocytes, platelets, and endothelial cells and their relevance for cardiovascular diseases. J Leukoc Biol 85:195–204. https://doi.org/10.1189/jlb.0708400

Rong M, Wang C, Wu Z et al (2014) Platelets induce a proinflammatory phenotype in monocytes via the CD147 pathway in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 16:478. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-014-0478-0

Yago T, Tsukuda M, Minami M (1999) P-selectin binding promotes the adhesion of monocytes to VCAM-1 under flow conditions. J Immunol 163:367–373

Van Wely CA, Blanchard AD, Britten CJ (1998) Differential expression of α3 fucosyltransferases in Th1 and Th2 cells correlates with their ability to bind P-selectin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 247:307–311. https://doi.org/10.1006/bbrc.1998.8786

Shafqat H, Gourdin T, Sion A (2018) Immune-related adverse events are linked with improved progression-free survival in patients receiving anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy. Semin Oncol 45:156–163

Knutson KL, Disis ML (2005) Tumor antigen-specific T helper cells in cancer immunity and immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother 54:721–728

Lim SY, Lee JH, Gide TN et al (2019) Circulating cytokines predict immune-related toxicity in melanoma patients receiving anti-PD-1–based immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res 25:1557–1563. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-2795

Acknowledgements

SV was supported by “Fondo Investigaciones Sanitarias” and a participant in the Program for Stabilization of Investigators the “Direcció i d’Estrategia i Coordinació del Departament Salut de la Generalitat de Catalunya.”

Funding

This work was supported by the Bristol Myers Squibb.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors were involved in revising intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be published. CZ, LPS, LAL and MAO performed cellular staining and flow cytometry analysis and ELISAs. CZ and LPS and MAO analysed results of flow cytometry and ELISAS; MR, GAP, IS, ABJ, JSL, OG, JGD, ABM, and MMT collected samples and clinical data; CZ and SVA performed statistical analysis. CZ, MR, MMT, and SVA wrote the manuscript. MMT and SVA design the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have not conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and approved by the Researchs Ethics Board of Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona (IIBSP-PDL-2017-82).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

262_2020_2793_MOESM2_ESM.tif

Supplementary file2 Supplementary Fig.1 Association of percentage of circulating CD4+PLT+ and CD14+PLT+ with the presence of irAEs. Percentage of CD4+PLT+ and CD14+PLT+ complexes in (A-B) non-irAEs vs irAEs groups, (C-D) grade of irAEs (0-≥3) and (E-F) number of irAEs per patient. The statistical analysis was performed using the t-test. *p<0.05 (TIF 484 kb)

262_2020_2793_MOESM3_ESM.tif

Supplementary file3 Supplementary Fig. 2 The association of platelet blood levels, the percentage and levels of activated platelets, the ratio of PLT/CD4+ and PLT/CD14+ and plasmatic levels of IFNɣ, IL-17 and IL-10 with irAE manifestation. The dot plots show (A) Platelet blood levels (PLT/µL), (B) the percentage of activated platelets, (C) the levels of activated platelets (PLT CD62P+/µL), (D) the ratio of PLT/CD4+, (E) the ratio of PLT/CD14+, pg/mL of (F) IFNɣ, (G) IL-17 and (H) IL-10 according to non-irAE and irAE groups. An unpaired t-test was used for the analysis of PLT/µL, % PLT CD62P+ and PLT CD62P+/µL, and the Mann-Whitney test for the analysis of the PLT/CD4+, PLT/CD14+, IFNɣ, IL-17 and IL-10 ratios (TIF 604 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zamora, C., Riudavets, M., Anguera, G. et al. Circulating leukocyte–platelet complexes as a predictive biomarker for the development of immune-related adverse events in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients receiving anti-PD-(L)1 blocking agents. Cancer Immunol Immunother 70, 1691–1704 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00262-020-02793-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00262-020-02793-4