Abstract

Rationale

Observing responses bring sensory receptors into contact with environmental stimuli. In the observing-response procedure, periods in which an operant response (e.g. pressing a lever) is reinforced by drug deliveries alternate with periods in which this response is never reinforced (i.e. extinction). These alternating periods of drug availability versus extinction are not signaled. Observing responses (i.e. presses on a second lever) produce brief stimuli signaling whether drug is available or not for responses on the first lever. Little is known about how parameters of the drug reinforcer affect drug-stimulus observing.

Objectives

The effects of changes in the unit price (responses/reinforcer magnitude) of self-administered ethanol on rats' observing were examined. Also, the effects of an observing-response-produced ethanol stimulus on ethanol consumption were examined by comparing consumption during signaled and unsignaled periods of ethanol availability.

Methods

Rats self-administered oral ethanol in the observing-response procedure. The unit price of ethanol in the observing-response procedure was increased by increasing the response requirement for ethanol across conditions.

Results

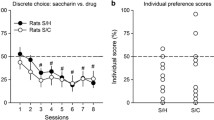

Observing and response rates on the ethanol lever increased and then decreased with increases in the unit price of ethanol. However, ethanol-lever responding and ethanol consumption during periods when ethanol was available were less sensitive to increases in price when the observing-response-produced ethanol stimulus was present.

Conclusions

Observing varies as an orderly function of unit price of a drug reinforcer, and drug stimuli produced by observing responses can make drug consumption less sensitive to increases in price. This procedure may provide an animal model of both attending to drug stimuli and the resultant effects of these stimuli on drug taking.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bickel WK, DeGrandpre RJ (1996) Modeling drug abuse policy in the behavioral economics laboratory. In: Green L, Kagel J (eds) Advances in behavioral economics (vol 3). Ablex, New York, pp 69–95

Bickel WK, DeGrandpre RJ, Higgins ST, Hughes JR (1990) Behavioral economics of drug self-administration: functional equivalence of response requirement and drug dose. Life Sci 47:1501–1510

Bickel WK, DeGrandpre RJ, Higgins ST (1993) Behavioral economics: a novel experimental approach to the study of drug dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend 33:173–192

Bienkowski P, Koros E, Kostowski W, Bogucka-Bonikowska A (2000) Reinstatementof ethanol seeking in rats: behavioral analysis. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 66:123–128

Carter BL, Tiffany ST (1999) Meta-analysis of cue-reactivity in addiction research. Addiction 94:327–340

Ciccocioppo R, Angeletti S, Weiss F (2001) Long-lasting resistance to extinction of response reinstatement induced by ethanol-related stimuli: role of genetic ethanol preference. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 25:1414–1419

DeGrandpre RJ, Bickel WK, Higgins ST, Hughes JR, Laying MP, Badger G (1993) Unit price as a useful metric in analyzing effects of reinforcer magnitude. J Exp Anal Behav 60:641–666

Dinsmoor JA (1983) Observing and conditioned reinforcement. Behav Brain Sci 6:693–728

Dinsmoor JA (1985) The role of observing and attention in establishing stimulus control. J Exp Anal Behav 43:365–381

Ehrman RN, Robbins SJ, Bromwell MA, Lankford ME, Monterosso JR, O'Brien CP (2002) Comparing attentional bias to smoking cues in current smokers, former smokers, and non-smokers using a dot-probe task. Drug Alcohol Depend 67:185–191

Estes WK (1948) Discriminative conditioning. II. Effects of a pavlovian conditioned stimulus upon a subsequently established operant response. J Exp Psychol 38: 173–177

Falk JL (1994) The discriminative stimulus and its reputation: Role in the instigation of drug abuse. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 2:43–52

Fantino E (1977) Conditioned reinforcement: choice and information. In: Honig WK, Staddon, JER (eds) Handbook of operant behavior. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J., pp 313–339

Field M, Duka T (2002) Cues paired with a low dose of alcohol acquire conditioned incentive properties in social drinkers. Psychopharmacology 159:325–334

Gaynor ST, Shull RL (2002) The generality of selective observing. J Exp Anal Behav 77:171–187

Hursh SR (1980) Economic concepts for the analysis of behavior. J Exp Anal Behav 34:219–238

Hursh SR (1984) Behavioral economics. J Exp Anal Behav 42:435–452

Hursh SR, Raslear TG, Shurtleef D, Bauman R, Simmons L (1988) A cost benefit analysis of demand for food. J Exp Anal Behav 50:419–440

Johnsen BH, Laberg JC, Cox WM, Vaksdal A, Hugdahl K (1994) Alcoholic subjects' attentional bias in the processing of alcohol-related words. Psychol Addict Behav 8:111–115

Katner SN, Magalong BS, Weiss FW (1999) Reinstatement of alcohol-seeking behavior by drug-associated discriminative stimuli after prolonged extinction in the rat. Neuropsychopharmacology 20:471–479

Kelleher RT, Riddle WC, Cook L (1962) Observing responses in pigeons. J Exp Anal Behav 5:3–13

Keppel G (1991) Design and analysis: a researcher's handbook 3rd edn. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.

Krank MD (1989) Environmental signals for ethanol enhance free-choice ethanol consumption. Behav Neurosci 103:365–372

Lieberman DA (1972) Secondary reinforcement and information as determinants of observing behavior in monkeys (Macaca mulatta). Learn Motiv 3:341–358

Lubman DI, Peters LA, Mogg K, Bradley BP, Deakin JFW (2000) Attentional bias for drug cues in opiate dependence. Psychol Med 30:169–175

Ludwig AM, Wikler A, Stark LH (1974) The first drink: psychobiological aspects of craving. Arch Gen Psychiatry 30:539–547

Med-Associates (1999) Med-PC for Windows. Med-Associates, St Albans, Vt., USA

Morse WH, Skinner BF (1958) Some factors involved in the stimulus control of operant behavior. J Exp Anal Behav 1:103–107

National Research Council (1996) Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. National Academy Press,Washington D.C.

Nevin JA, Tota ME, Torquato RD, Shull RL (1990) Alternative reinforcement increases resistance to change: Pavlovian or operant contingencies? J Exp Anal Behav 53:359–379

Panlilio LV, Weiss SJ, Schindler CW (2000) Effects of compounding drug-related stimuli: escalation of heroin self-administration. J Exp Anal Behav 73:211–224

Rachlin H, Green L, Kagel J, Battalio R (1976) Economic demand theory and psychological studies of choice. In: Bower GH (ed) The psychology of learning and motivation (vol 10). Academic Press, New York, pp 129–154

Ranaldi R, Roberts DCS (1996) Initiation, maintenance and extinction of cocaine self-administration with and without conditioned reward. Psychopharmacology 128:89–96

Rescorla RA, Solomon RL (1967) Two-process learning theory: relationships between Pavlovian conditioning and instrumental learning. Psychol Rev 74:151–182

Robinson TE, Berridge KC (1993) The neural basis of drug craving: An incentive-sensitization theory of addiction. Brain Res Rev 18:247–291

Ryan F (2002) Detected, selected, and sometimes neglected: Cognitive processing of cues in addiction. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 10:67–76

Samson HH (1986) Initiation of ethanol reinforcement using a sucrose-substitution procedure in food- and water-sated rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 10:436–442

Samuelson PA, Nordhaus WD (1985) Economics. McGraw-Hill, New York

Shahan TA (2002a) The observing-response procedure: a novel method to study drug-associated conditioned reinforcement. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 10:3–9

Shahan TA (2002b) Observing behavior: Effects of rate and magnitude of primary reinforcement. J Exp Anal Behav 78:161–178

Spear DJ, Katz JL (1991) Cocaine and food as reinforcers: effects of reinforcement magnitude and response requirement under second-order fixed-ratio and progressive ratio schedules. J Exp Anal Behav 56:261–275

Stewart J, de Wit H, Eikelboom R (1984) Role of unconditioned and conditioned drug effects in the self-administration of opiates and stimulants. Psychol Rev 91:251–268

Townshend JM, Duka T (2001) Attentional bias associated with alcohol cues: differences between heavy and occasional social drinkers. Psychopharmacology 157:67–74

Weiss SJ (1978) Discriminated response and incentive processes in operant conditioning: a two-factor model of stimulus control. J Exp Anal Behav 30:361–381

Wikler A (1948) Recent progress in research on the neurophysiological basis of morphine addiction. Am J Psychiatry 105:329–338

Williams BA (1988) Reinforcement, choice, and response strength. In: Atkinson RC, Herrnstein, RJ (eds) Stevens' handbook of experimental psychology (vol 1): perception and motivation (2nd edn). Wiley, Oxford, pp 167–244

Woods JH, Winger GD (2002) Observing responses maintained by stimuli associated with cocaine or remifentanil reinforcement in rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology 163:345–351

Wyckoff LB (1952) The role of observing responses in discrimination learning. Psychol Rev 59:431–442

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by USPHS grant AA12891. The author thanks Amy Odum for her comments on a previous version of the paper, Gary Badger for providing statistical consultation, and Jessica Doucette, Jessica Milo, and David Savastano, for their help conducting this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shahan, T.A. Stimuli produced by observing responses make rats' ethanol self-administration more resistant to price increases. Psychopharmacology 167, 180–186 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-003-1390-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-003-1390-5