Abstract

In the present study, we evaluated an alternative testing strategy to quantitatively predict the in vivo developmental toxicity of the synthetic hormone diethylstilbestrol (DES). To this end, a physiologically based kinetic (PBK) model was defined that was subsequently used to translate concentration–response data for the in vitro developmental toxicity of DES, obtained in the ES-D3 cell differentiation assay, into predicted in vivo dose–response data for developmental toxicity. The previous studies showed that the PBK model-facilitated reverse dosimetry approach is a useful approach to quantitatively predict the developmental toxicity of several developmental toxins. The results obtained in the present study show that the PBK model adequately predicted DES blood concentrations in rats. Further studies revealed that DES tested positive in the ES-D3 differentiation assay and that DES-induced inhibition of the ES-D3 cell differentiation could be counteracted by the estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) antagonist fulvestrant, indicating that the in vitro ES-D3 cell differentiation assay was able to mimic the role of ERα reported in the mode of action underlying the developmental toxicity of DES in vivo. In spite of this, combining these in vitro data with the PBK model did not adequately predict the in vivo developmental toxicity of DES in a quantitative way. It is concluded that although the EST qualifies DES as a developmental toxin and detects the role of ERα in this process, the ES-D3 cell differentiation assay of the EST apparently does not adequately capture the processes underlying DES-induced developmental toxicity in vivo.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The development of reliable non-animal based testing strategies is of main interests in current human safety testing of chemicals. Especially, the development of in vitro testing strategies in which adverse effects of chemicals on cells in culture can be detected is considered promising. However, data derived from in vitro models are as such inadequate for risk assessment, since risk assessment requires in vivo dose–response data from which points of departure (PODs) can be derived for defining safe exposure levels, whereas in vitro models provide information on concentration–response relationships. Therefore, to use in vitro data for risk assessment, in vitro concentration–response curves need to be translated to in vivo dose–response curves. This translation can be achieved through so-called physiologically based kinetic (PBK) modelling-facilitated reverse dosimetry approach. A PBK model is a set of mathematical equations that together describe the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) characteristics of a compound within an organism and can be used to relate external doses to internal (e.g., blood or tissue) concentrations. In the reverse dosimetry approach, the concentrations causing toxicity in the in vitro model are considered equal to the blood or tissue concentrations that would cause toxicity in the in vivo situation. As such, PBK models can be used to predict in vivo toxicity dose levels based on toxic effect concentrations obtained in in vitro assays to derive a point of departure (POD) for risk assessment, such as a benchmark dose (BMD) or a lower confidence limit of the BMD, the BMDL (Louisse et al. 2010, 2017; Strikwold et al. 2013).

Previously, we have shown that reverse dosimetry of in vitro developmental toxicity data obtained in the ES-D3 differentiation assay of the embryonic stem cell test (EST) can result in an adequate quantitative prediction of in vivo dose-dependent developmental toxicity for a wide range of compounds including glycol ethers, retinoic acid, a series of phenols, and tebuconazole (Li et al. 2017; Louisse et al. 2010, 2015; Strikwold et al. 2017).

To further explore the potential applicability of the reverse dosimetry approach, examples with more chemicals with diverse physico-chemical properties and modes of action are needed. The present study assesses whether the developmental toxicity of the xeno-estrogen diethylstilbestrol (DES) can be predicted using PBK modelling-based reverse dosimetry approach.

DES is a synthetic estrogen that was first produced for hormonal therapy in 1938 (IARC 2012). DES was prescribed to pregnant women to prevent potential miscarriages and premature delivery, by acting as an estrogen analogue (IARC 2012). However, DES use during pregnancy showed no preventive effect against miscarriages and it even caused adverse health effects in these women, such as breast cancer, and in their children and grandchildren, such as cell adenocarcinoma of the cervix and vagina in daughters and cancer of the testis in sons (Giusti et al. 1995; IARC 2012). Moreover, animal studies showed that DES caused developmental toxicity, including embryonic death and resorptions (Cornwall et al. 1984; Nagao and Yoshimura 2009; Wardell et al. 1982). Considering the underlying mode of action for adverse effects of DES, it has been reported that the estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) is needed to induce adverse developmental effects in neonates including induction of malformations and phenotypic changes in the neonatal reproductive tracts of female and male mice (Couse et al. 2001; Couse and Korach 2004; Prins et al. 2001). This was concluded from experiments in ERα knock-out mice, in which exposure to DES no longer induced alteration of the expression of Hoxa10, Hoxa11, and Wnt7 genes, or alteration in the weight of the seminal vesicle in the male and in the phenotype of the reproductive tract of the female, providing clear evidence for a role for ERα in mediating the adverse effects of neonatal DES exposure in the reproductive tract.

The aim of the present study was to assess whether the in vivo dose-dependent developmental toxicity caused by DES can be estimated using a combination of an in vitro assay for developmental toxicity and PBK modelling-based reverse dosimetry. In addition, it was investigated whether the role of ERα observed in vivo could also be demonstrated for the in vitro developmental toxicity of DES. To this end, in vitro concentration–response data for DES were quantified in the ES-D3 cell differentiation assay of the EST and a PBK model for DES in the rat was developed. In a next step, the PBK model was used to translate the in vitro EST data to predicted in vivo dose–response data for developmental toxicity of DES that were subsequently compared with the available literature data from in vivo studies reporting developmental toxicity of DES. Finally, DES was tested in the ES-D3 cell differentiation assay in the presence of the ERα antagonist fulvestrant, to investigate whether with respect to the reported role of ERα in DES-induced disturbance of development; the in vitro model mimics the in vivo situation.

Materials and methods

Materials

Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was purchased from Acros Organics (Geel, Belgium). DES, reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH), uridine 5′-diphosphoglucuronic acid (UDPGA), adenosine 3′-phosphate 5′-phosphosulfate (PAPS) lithium salt hydrate, acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl CoA) sodium salt, alamethicin, magnesium chloride, sodium phosphate, sodium chloride, and rat serum were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (Zwijndrecht, The Netherlands). Pooled male and female Sprague–Dawley rat liver S9 fractions were purchased from Tebu-bio (Heerhugowaard, the Netherlands). Rapid equilibrium dialysis (RED) devices were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Bleiswijk, The Netherlands). Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was purchased from Invitrogen (Breda, The Netherlands).

Cell line and culture conditions

The murine mouse embryonic stem (ES-D3) cell line was purchased from ATCC/LGC (Wesel, Germany). The cells were maintained in low osmo Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (low osmo DMEM, GE Healthcare life sciences, Logan, Utah, USA) in 75 cm2 polystyrene cell culture flasks (Corning, The Netherlands), supplemented with 15% heat-inactivated ES cell qualified fetal calf serum (ATCC/LGC, Wesel, Germany), 50 U/ml penicillin with 50 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen, Breda, The Netherlands), and 2 mM l-glutamine (Invitrogen), at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere. Cells were kept undifferentiated with 1000 U/ml murine leukemia inhibiting factor (LIF, Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) and sub-cultured every 2–3 days using non-enzymatic cell dissociation solution (Sigma-Aldrich) to detach the cells.

Cytotoxicity assay with ES-D3 cells

Cytotoxicity of DES was determined using the WST-1 assay. This assay measures the formation of the water-soluble formazan product from WST-1 by mitochondrial succinate-tetrazolium reductase enzymes in non-exposed cells (control) and cells exposed to the test compound. ES-D3 cells were exposed to DES (Sigma-Aldrich) for the duration of 3 and 5 days. Briefly, cells were seeded in 96-well plates (Greiner bio-one, Alphen aan den Rijn, The Netherlands) at a concentration of 1 × 104 cells/ml in 100 μl culture medium in the absence of LIF and incubated for 1 day to allow cell adherence. Then, the cells were exposed to DES or fulvestrant at concentrations up to 100 μM in triplicate (final solvent concentration 0.2% DMSO) and subsequently cultured for 3 or 5 days at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere. The solvent DMSO (0.2%) was used as a negative control and 5 µM 5-fluorouracil served as a positive control in all cytotoxicity assays. After exposure for 3 or 5 days, 20 μl WST-1 reagents (Roche, Woerden, The Netherlands) were added to each well and plates were incubated for an additional 3 h. Then, absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a SpectraMax M2 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, USA). Three independent experiments were performed. The cell viability was expressed as percentage of the solvent control, with the solvent control set at 100%. Cytotoxicity data were analysed for significant effects compared to the solvent control using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) in GraphPad Prism 5.04 software.

Differentiation assay with ES-D3 cells

Differentiation assay was performed to detect the effect of DES on the differentiation of ES-D3 cells into contracting cardiomyocytes. On day 1, droplets of 20 μl cell suspension (3.75 × 104 cells/ml) were placed as hanging drops, containing the test compound (DES) at concentrations ranging from 0.3 to 100 μM (final solvent concentration as 0.2% DMSO), on the inner side of the lid of a 96-well plate. Sterile lids of Eppendorf tubes were placed on the corner wells of the plates to prevent contact of the drops with the plate. The wells of the 96-well plate were filled with 200 μl phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, Invitrogen), and the plate was sealed with microspore tape (3 M, Neuss, Germany) to prevent evaporation of the hanging drops. Plates were incubated for 3 days at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere. In the drops, cells formed embryonic bodies (EBs), which were transferred to non-tissue culture-treated Petri dishes (diameter 6 cm, Greiner) containing 5 ml of medium with the test compound at the relevant test concentration. On day 5, the EBs were transferred to wells of a 24-well plate (one EB per well) containing 1 ml of medium with test compound. On day 10, the number of wells containing contracting cardiomyocytes was determined by visual inspection using a light microscope. A solvent control (0.2% DMSO in culture medium) was included in each experiment. Tests were accepted for further analysis if at least 21 of the 24 wells of the solvent control contained contracting cardiomyocytes. Three independent experiments were performed. The results were expressed as percentage of the solvent control, with the solvent control set at 100%.

To assess whether effects on ES-D3 cell differentiation were mediated via the ERα, also studies were performed in which the effects of DES on the differentiation of ES-D3 cells into contracting cardiomyocytes were assessed in the presence of the ERα antagonist fulvestrant. To that end, first, a concentration of fulvestrant was determined that did not affect ES-D3 cell differentiation by itself, which was then applied in the co-exposure studies. Final solvent concentrations in these studies were also 0.2% DMSO.

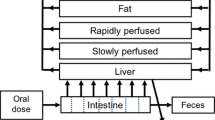

Development of a PBK model of DES in rats

The previously developed PBK model of E2 and BPA (Zhang et al. 2018) was used as the starting point to develop the PBK model that describes the kinetics of DES in rats. The schematic representation of the model is shown in Fig. 1. The PBK model includes individual compartments for blood, fat, intestine, liver, rapidly perfused tissue, and slowly perfused tissue. The physiological and anatomical parameter values were taken from the literature (Brown et al. 1997) and are presented in Table 1. To describe the intestinal transition of DES, the intestine compartment was divided into seven sub-compartments. The transition in the small intestine was assumed to be the same for all the sub-compartments. The apparent permeability coefficient (Papp value) was used to derive the absorption rate constant (ka) for uptake of the parent compound from the intestines into the liver. This input Papp value was estimated based on the quantitative structure–activity relationship (QSAR) approach of Hou et al. (Hou et al. 2004). The chemical-dependent input parameter of this approach was the polar surface area (PSA), which is 40.46 for DES. The in vitro Log Papp value can be estimated using the formula: Log (Papp, in vitro) = − 4.28–0.011 × PSA. This value was used to calculate the in vivo Papp value using the following equation: Log Papp, in vivo = 0.6836 × Log Papp, in vitro − 0.5579 (Sun et al. 2002). Then, the absorption rate constant (ka, L/h) was estimated using the in vivo Papp value (expressed in dm/h) times the respected intestine surface area (SA, in dm2) of each sub-compartment (Zhang et al. 2018).

The tissue/blood partition coefficients of DES were estimated based on the quantitative property–property relationship (QPPR) approach of DeJongh et al. (DeJongh et al. 1997). The input parameter of this approach was the octanol–water partition coefficient (Pow), the Log Pow of DES is 5.07 (Selassie et al. 1999). The estimated partition coefficients are presented in Table 1.

The assumption was made that the estrogenic effects of DES are caused by the parent compound, not by the metabolites (Korach et al. 1989), and the clearance was resulted from hepatic clearance only, not by the renal clearance. The hepatic metabolism of the parent compound was determined in rat liver S9 fractions (Zhang et al. 2018), as described below. The PBK model code was described in Supplementary material 1. The PBK model equations were coded and numerically integrated in Berkeley Madonna 8.0.1 (UC Berkeley, CA, USA), using the Rosenbrock’s algorithm for stiff systems.

Determination of the model parameter value for hepatic clearance

The in vitro intrinsic clearance (CLint) was determined using a substrate depletion approach, and these data were scaled to in vivo to describe the hepatic clearance of the parent compound in the PBK model. The CLint of DES was determined in incubations with male or female Sprague–Dawley rat liver S9 fractions in the presence of relevant co-factors (NADPH, UDPGA, PAPS, and acetyl CoA) for phase I and II metabolism. Our previous study has shown that the CLint value obtained from incubations with S9 and all co-factors together in one mixture is similar to the sum of CLint values derived from incubations for individual reactions (with individual co-factors) (Zhang et al. 2018). Therefore, in the current study, we determined CLint of DES by incubating the substance with all co-factors together in one mixture, in the presence of liver S9 fraction from male or female Sprague–Dawley rats. Incubations with female rats were performed to obtain kinetic parameters for the PBK model when used to predict developmental toxicity. However, since the in vivo kinetic data on DES that were used for evaluation of the PBK model were obtained in male rats, also the kinetic parameters for clearance in male rats were determined. One requirement of the substrate depletion approach is that the initial concentration of the parent compound should be below the Michaelis–Menten constant (Km) for the respective conversions. In the current study, the test concentration of DES was 3 μM, which is 25.6-fold below the lowest Km value reported for the metabolism of DES by liver microsomes of rats (Roy et al. 1992). To determine the hepatic clearance, 3 μM DES (final concentration) was incubated with 0.5 mg/ml liver S9, 3 mM NADPH, 5 mM UDPGA, 0.2 mM PAPS, 0.5 mM acetyl CoA, 5 mM MgCl2, and 0.025 mg/ml alamethicin in 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). The total incubation volume was 200 μL. The incubation time points were 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8.5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, and 45 min. To terminate the reaction, 100 µL cold acetonitrile (ACN) were added to the mixture and the Eppendorf tubes were put on ice for 30 min. Subsequently, tubes were centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 10 min (CT 15RE, Hitachi Koki Co., Ltd) and the supernatant was collected for UPLC analysis. For each incubation time point, a corresponding control incubated in the absence of co-factors was included. For all incubations, three independent replicates were performed.

The ratio of remaining DES between incubation samples (Ccompound) and the corresponding control (incubation without co-factors, Ccontrol) was calculated for all the incubation time points. The elimination curve of the parent compound [ln(Ccompound/Ccontrol)] against incubation time was derived. The elimination rate constant (k, min−1), which is the absolute value of the slope of the linear part of the elimination curve, was used to calculate the in vitro clearance (CLint, in vitro) using the following equation: CLint, in vitro (µL/min/mg protein) = incubation volume (µL)/protein amount in the mixture (mg) × elimination rate constant (k, min−1) (Obach 1999; Sjogren et al. 2009). The in vitro CLint value of the parent compound was then scaled to the whole liver, assuming the S9 protein concentration in rat liver to be 87 g protein/kg liver (Chiu and Ginsberg 2011).

Ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) analysis

A UPLC H_Class system (Waters Acquity) equipped with a Waters BEH C18 (1.7 µm, 2.1 × 50 mm) column was used. The temperature was set at 40 °C for the column and 5 °C for the samples. The injection volume was 3.5 µL and the flow rate was 0.45 ml/min. The mobile phase consisted of nanopure water as solvent A and ACN as solvent B. The gradient started at 65% solvent A, changed to 50% solvent A in the next 2 min, decreased to 0% solvent A in 1 min, and was kept at these conditions for another 2 min. Then, the gradient was changed to the initial conditions in 2 min and kept at these conditions for 1 min. The total running time was 8 min. The quantification of DES in each incubation was achieved by integrating the peak area at 245 nm and comparison to the peak areas of a calibration curve made using the commercially available reference compound.

PBK model evaluation

To evaluate the performance of the PBK model developed, the predicted time-dependent blood concentrations of DES were compared to the time-dependent blood concentrations of DES in rats reported in the literature upon intravenous and oral exposure (Ako 2011; Thompson and Klaassen 1985).

A sensitivity analysis was performed to locate the influential parameters of the PBK model on the model prediction of the maximum blood concentration (Cmax) of DES. As described in a previous study (Evans and Andersen 2000), normalized sensitivity coefficients (SC) were calculated according to the following equation: SC = (C′−C)/(P′–P) × (P/C), with C and C′ representing the initial and modified values of the model output, and P and P′ the initial and modified parameter values. A 5% increase of parameter value was chosen to assess the effect of a change in parameter on the prediction of Cmax. Each parameter was individually analysed by changing one parameter value at a time and keeping the others the same. In addition, the total tissue fraction and blood flow fraction should be kept as 1. The sensitivity analysis was conducted for oral exposure to a single dose of 4 mg/kg bw DES, which was the dose applied in the in vivo kinetic study of Ako (2011).

Translation of in vitro concentration–response data into predicted in vivo dose–response data using PBK modelling-based reverse dosimetry

The PBK modelling-based reverse dosimetry approach was used to quantitatively predict the dose levels that are required to reach concentrations of DES in blood that were applied in the in vitro differentiation assay. It is assumed that the toxicity is induced by the fraction unbound (fub) of the parent compound. To take differences in the unbound fraction in the in vitro incubation medium and in vivo blood into account, the fub values of DES in vitro and in vivo were determined by rapid equilibrium dialysis (RED).

Determination of fraction unbound of DES in rat serum and in in vitro medium

Rapid equilibrium dialysis (RED) was performed to determine the fub of DES in the in vitro assay medium of the cell differentiation assay and in rat serum by following the protocol described by Waters et al. (Waters et al. 2008). The assay medium of the ES-D3 cell differentiation assay contained 15% FCS. 300 μL sample containing 5 μM of DES (final concentration) in the in vitro assay medium or in rat serum was added to the plasma chamber and 500 μL PBS was added to the buffer chamber. After a 5-h incubation at 37 °C at 250 rpm on an orbital shaker, the system reaches equilibrium (van Liempd et al. 2011). Then, 25 μL of post-dialysis samples were collected from the plasma chamber and the buffer chamber in different tubes. According to the manufactural protocol, 25 μL of buffer (PBS) were added to the samples from the plasma chamber and the same volume of assay medium or rat serum was added to the samples taken from the buffer chamber. This was done to equalize the samples with respect to the protein concentration for analysis. To precipitate the protein and release the compound, 300 μL cold ACN/nanopure water (90/10) was added to all the samples. The samples were put on ice for 30 min and subsequently centrifuged for 15 min at 15,000×g (CT 15RE, Hitachi Koki Co., Ltd). The supernatants were collected for UPLC analysis to quantify the concentration of DES in each chamber. The fraction unbound (fub) can be calculated based on the equation: fub = (concentration in buffer chamber/concentration in plasma chamber) (Waters et al. 2008). All the measurements were performed in triplicate in three independent studies.

PBK modelling-based reverse dosimetry

The in vivo dose-dependent developmental toxicity was assumed to depend on the maximum blood concentration (Cmax) of DES. The in vitro effect concentrations were corrected for differences in protein binding with the in vivo situation, using the results of the analysis of fub described above. For reverse dosimetry, the in vitro unbound concentration (Cub, in vitro) was set equal to the in vivo unbound (Cub, in vivo), which is reflected by the following equations: Cub, in vivo = Cub, in vitro, so Ctotal in vivo × fub in vivo = Ctotal in vitro × fub in vitro, where fub, in vivo and fub, in vitro are the fraction unbound in rat serum and in the in vitro assay medium determined from the RED assay. Then, the nominal blood concentration in rat can be described as: Ctotal in vivo = Cub, in vivo/fub, in vivo = Cub, in vitro/fub, in vivo = (Ctotal,in vitro × fub, in vitro)/fub, in vivo. Ctotal in vivo was subsequently used as Cmax to calculate the corresponding in vivo dose level using the PBK model. Performing this exercise for all the in vitro test concentrations, the in vitro concentration–response curve was translated into predicted in vivo dose–response curve.

Evaluation of the quantitative prediction of dose-dependent developmental toxicity of DES

To evaluate the quantitative prediction of the developmental toxicity of DES using the developed PBK modelling-based reverse dosimetry approach, the predicted dose–response data derived from the in vitro differentiation assay were compared with the dose–response data derived from in vivo development toxicity studies (Cornwall et al. 1984; Wardell et al. 1982).

Furthermore, the benchmark dose (BMD) values derived from the predicted dose–response data were compared with the BMD values obtained from in vivo toxicity data. The BMD analysis was performed using the exponential model for dichotomous data of PROAST software from The National Institute for Public Health and the Environment of the Netherlands (RIVM) version 38.9 (Slob 2018). The benchmark response (BMR) was defined as a 10% change compared to the control. The lower (BMDL) and upper (BMDU) limits of the 95% confidence interval on the BMD10 can be derived from the software only when the data can be adequately modelled. The BMD analyses were performed on the predicted dose–response data obtained from the in vitro differentiation assay and the in vivo developmental toxicity data reported in the literature. In vitro EST data were analysed using the same BMD approach, fitting the concentration–response curve to determine the concentration associated with a BMR of 50%. A 50% change in the number of beating EBs was selected as the BMR to calculate the benchmark concentrations for the differentiation (BMC50).

Results

Cytotoxicity and inhibition of ES-D3 cell differentiation by DES

To study the in vitro developmental toxicity of DES, the effect of the compound on the differentiation of ES-D3 cells into contracting cardiomyocytes was evaluated. First, the WST-1 assay upon both 3-day and 5-day exposure was performed to evaluate the cytotoxic effects of DES on the ES-D3 cells (Fig. 2). The DES concentrations tested were non-cytotoxic up to 3 µM as determined in the 3-day and 5-day cytotoxicity assay. Starting from 10 µM, the cell viability started to decrease.

Concentration-dependent effects of DES on cell viability upon 3-day (open circle) and 5-day (filled square) exposure and on ES-D3 cell differentiation (open triangle). The figure presents data from three independent experiments. For the statistical analysis, ****p < 0.0001; ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05

Regarding the differentiation effect, DES induced a concentration-dependent inhibition of the differentiation of the ES-D3 cells into contracting cardiomyocytes (Fig. 3) at concentrations that were not yet cytotoxic, indicating that inhibitory effects on the differentiation of EBs are not due to cytotoxicity of DES.

a Concentration-dependent effects of fulvestrant on cell viability upon 3-day (open circle) and 5-day (open square) exposure and on inhibition of ES-D3 cell differentiation (open triangle). b Effect of fulvestrant on DES‐induced inhibition of ES-D3 cell differentiation. ES-D3 cells were exposed to DES in the absence (open circle) or presence (open triangle) of 150-nM fulvestrant (n = 3). For the statistical analysis, ****p < 0.0001; ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05

Effect of the ERα antagonist fulvestrant on DES-induced inhibition of ES‐D3 cell differentiation

Cytotoxicity and ES-D3 differentiation assays were performed to evaluate the toxicity and the inhibition of ES-D3 differentiation by the ERα antagonist fulvestrant. The results indicate that fulvestrant is not cytotoxic up to 100 µM (Fig. 3a). Fulvestrant also caused a concentration-dependent inhibition of ES-D3 cell differentiation into contracting cardiomyocytes (Fig. 3a). Based on these results, a concentration of 150 nM fulvestrant was selected to investigate the effect of the ERα antagonist on DES-induced inhibition of ES-D3 differentiation, because, at this concentration, fulvestrant did not interfere with the differentiation of the ES-D3 cells, while 150 nM is considerably higher than the IC50 for binding of fulvestrant to the ERα of 0.8–0.9 nM as reported in the literature (Wakeling et al. 1991; Weir et al. 2016). Figure 3b reveals that DES-induced inhibition of ES-D3 cell differentiation is counteracted by the ERα-antagonist fulvestrant at 150 nM.

Development of a PBK model for DES in rats

The developed PBK model code is presented in Supplementary material 1. The values for physiological and anatomical parameters were taken from literature (Brown et al. 1997), and are presented in Table 1.

The apparent permeability coefficient (Papp) value was estimated using the QSAR approach of Hou et al. (Hou et al. 2004). The calculated Papp, in vitro value is 18.8 × 10−6 cm/s for DES. This value was used to estimate the in vivo Papp value, which was used to describe the uptake of DES from the intestines to the liver from the seven sub-compartments of the intestines.

The hepatic clearance was considered the driving clearance process determining the body clearance of DES. The in vitro hepatic CLint value of DES was determined by incubating the parent compound with co-factors of phase I and phase II metabolism together with male or female rat liver S9 in one mixture. The depletion curves are presented in supplementary material 2 and the hepatic CLint values were listed in Table 1.

PBK model evaluation

To evaluate the model predictions, the predicted time-dependent blood concentrations of DES were compared with available in vivo kinetic data reported in the literature. Figure 4 presents the time-dependent blood concentration of DES obtained from the in vivo studies (symbols) and the predicted time-dependent blood concentration curves (lines) upon intravenous (IV) (Fig. 4a) or oral (Fig. 4b) administration. The difference of maximum blood concentration (Cmax) upon oral administration between the prediction and the in vivo kinetics data was 2.3-fold. This comparison reveals that the developed PBK model can predict the blood concentration of DES upon IV and oral exposure quite well.

a Blood concentration of DES in rats upon intravenous administration. Symbols represent the average blood concentrations from the in vivo study of Thompson and Klaassen (Thompson and Klaassen 1985). Lines represent PBK model-based predictions of blood concentrations. Dose levels are as follows: 0.005 mg/kg bw (reversed triangles, straight line); 0.05 mg/kg bw (circles, dashed line); 0.5 mg/kg bw (squares, dotted line). b Blood concentration of DES in rats upon oral administration. Symbols represent the average blood concentrations when rats were exposed to a dose of 4 mg/kg bw/day as reported in the in vivo study of Ako (2011). Lines represent PBK model-based predictions of blood concentrations

For further evaluation of the model, a sensitivity analysis was performed. This sensitivity analysis was performed for the prediction of the Cmax upon oral exposure to a single oral dose of 4 mg/kg bw DES, which was used in the in vivo kinetic data of Ako (Ako 2011). The normalized sensitivity coefficients (SC) with an absolute value higher than 0.1 are displayed in Fig. 5. The results indicate that, among all the influential parameters, the prediction of the Cmax of DES in the PBK model is most sensitive to the fraction of liver tissue (VLc), the fraction of blood flow to the liver (QLc), parameters of intestines, the estimated in vivo Papp value, and the hepatic clearance (CLintS9).

Normalized sensitivity coefficients of the PBK model parameters for the predicted Cmax of DES in blood after oral administration of 4 mg/kg bw which was tested in the in vivo kinetic study (Ako 2011). All model parameters with a normalized sensitivity coefficient with an absolute value higher than 0.1 are shown. VLc Fraction of liver tissue, VRc fraction of rapidly perfused tissue, QLc fraction of blood flow to liver, QRc fraction of blood flow to rapidly perfused tissue, QSc fraction of blood flow to slowly perfused tissue, Papp, Caco-2 estimated in vivo Papp value, Vin intestine volume for intestinal sub-compartment, SAin intestinal surface area for intestinal sub-compartment, kin transfer rate within intestinal sub-compartments, PR rapidly perfused tissue/blood partition coefficient, PS slowly perfused tissue/blood partition coefficient, CLint experimental hepatic clearance of DES

Translation of the in vitro concentration–response data into quantitatively predicted in vivo dose–response data

The fub of DES in ES-D3 culture medium was 0.90 ± 0.09 and it was 0.65 ± 0.06 in rat serum. These values were used to correct for the differences in fraction unbound between in vivo and in vitro.

The in vitro concentration–response curves from the ES-D3 differentiation assay were translated into in vivo dose–response curves using PBK modelling-based reverse dosimetry approach. Data from two in vivo developmental toxicity studies of DES reported in the literature were used to evaluate the predictions and are presented in Table 3.1 and 3.2 in the Supplementary material 3. The predicted dose–response curve (Fig. 6, straight line) was compared with the in vivo dose–response curves derived from in vivo developmental toxicity studies reported in literature (Fig. 6, dashed lines). It can be concluded that the prediction based on in vitro ES-D3 differentiation assay data underestimates the in vivo developmental toxicity of DES by 3–4 orders of magnitude.

Predicted (straight line) and reported dose–response data for developmental toxicity of DES in rats reported in literature (squares and triangles with dashed lines) (Cornwall et al. 1984; Wardell et al. 1982), respectively. Predicted dose–response data were obtained using PBK modelling-facilitated reverse dosimetry approach based on data obtained from the ES-D3 cell differentiation assay

Evaluation of the prediction of dose-dependent developmental toxicity of DES

In the next step, a BMD analysis using the PROAST software was performed on the predicted dose–response data and on the in vivo toxicity data, resulting in the BMD values presented in Fig. 7. The BMR was defined as a 10% change compared to control, and the BMD10, BMDL10, and BMDU10 values were obtained. The BMD range between BMDL10 and BMDU10 is represented as a box and the BMD10 value is shown as the vertical line in the box (Fig. 7). The predicted BMD10 value of DES is 372–700-fold higher than the BMD10 values derived from the in vivo studies, while the BMDL10 is 202–442 and BMDU10 707–1107-fold higher than the BMDL10 and BMDU10 values derived from the in vivo studies. These results indicate that the developed PBK modelling-based reverse dosimetry approach of the in vitro ES-D3 differentiation assay underpredicts the developmental toxicity of DES in rats by up to about 3–4 orders of magnitude. The detailed results of the BMD analyses can be found in the Supplementary material 3 in Table 3.3, 3.4, and 3.6.

Comparison of the BMD10 values (including BMDL10 and BMDU10 values) derived from the predicted dose–response curve and from in vivo dose–response data for developmental toxicity of DES in rats. Predicted dose–response data were obtained by PBK modelling-based reverse dosimetry approach based on in vitro data from the ES-D3 cell differentiation assay and in vivo data were obtained from developmental toxicity assay studies reported in the literature (Cornwall et al. 1984; Wardell et al. 1982). BMD analysis was performed using the BMR as a 10% response change as compared to the control using PROAST. The results are presented as a box representing the range between the BMDL10 and BMDU10 values, giving the BMD10 values as a vertical line in the box

Comparison of different compounds inducing inhibition of embryonic stem cell differentiation and developmental toxicity in experimental animals

To obtain further insight in possible reasons underlying the inability to quantitatively predict the in vivo developmental toxicity of DES based on data from the EST and PBK modelling-based reverse dosimetry approach, the BMC50 values obtained in the EST for different classes of developmental toxins were compared with their in vivo BMD10 values (Fig. 8). Such data were available for retinoids (ATRA: all-trans-retinoic acid, 13-cis-RA, and acitretin), antifungal compounds (tebuconazole, propiconazole, prothioconazole, ketoconazole, and fenarimol), phenols (p-methylketophenol and p-fluorophenol), and glycol ethers (EGME: ethylene glycol monomethyl ether, EGEE: ethylene glycol monoethyl ether, EGBE: ethylene glycol monobutyl ether, and EGPE: ethylene glycol monophenyl ether (de Jong et al. 2009; Li et al. 2017; Louisse et al. 2010; Strikwold et al. 2017). Figure 8 also includes the data for DES, showing that DES is out of line with the other developmental toxins. Based on the data shown in Fig. 8a, the BMC50 in the EST for the developmental toxins, excluding DES, correlated (R2 = 0.62) with the BMD10 derived from the in vivo developmental toxicity data for these compounds. Plotting DES in this figure illustrates that the EST underestimates the developmental toxicity of DES, providing a BMC50 that is about 104-fold higher than what would be predicted based on the obtained correlation. Taking into account the kinetics of these compounds, Fig. 7b presents the correlation between the in vivo BMD10 and predicted BMD10 for p-methylketophenol, p-heptyloxyphenol, p-flurophenol, EGPE, EGBE, EGEE, EGME, ATRA, and DES. When taking kinetics into account, the correlation improves (R2 = 0.69, excluding DES). With this new correlation DES is still three orders of magnitude out of line. Based on the fact that the developed PBK model predicted the kinetics of DES quite well (Fig. 4), and the fact that DES is three orders of magnitude off line as compared to other model compounds when taking kinetics into account (Fig. 8b), it is concluded that the inability to predict the in vivo developmental toxicity by the PBK modelling-based reverse dosimetry of the in vitro data from the ES-D3 cell differentiation assay is likely to be due to the inability of this assay to accurately detect the developmental toxicity of DES in vivo in a quantitative way.

Comparison between in vivo BMD10 values for developmental toxicity for a BMC50 values in the ES-D3 cell differentiation assay and b predicted BMD10 values for DES and other developmental toxins for which ES-D3 cell differentiation assay data are available, including retinoids (ATRA: all-trans-retinoic acid, 13-cis-RA and Acitretin) (Louisse et al. 2011), antifungal compounds (tebuconazole, propiconazole, prothioconazole, ketoconazole, and fenarimol) (Li et al. 2015), phenols (p-methylketophenol and p-fluorophenol) (Strikwold et al. 2017), and glycol ethers (EGEE: ethylene glycol monoethyl ether, EGME: ethylene glycol monomethyl ether, EGBE: ethylene glycol monobutyl ether, and EGPE: ethylene glycol monophenyl ether) (de Jong et al. 2009). Compounds with the black triangle symbols are the compounds that previously gave good predictions with the PBK modelling-facilitated reverse dosimetry (Li et al. 2017; Louisse et al. 2010, 2015; Strikwold et al. 2017). The white triangle present the results of DES from the present study, while the white diamond presents the value that would have been in line with the other compounds. Correlations presented are calculated excluding the value for DES

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to develop an in vitro and in silico-based PBK model for DES and assess whether the in vivo developmental toxicity of DES can be quantitatively predicted by PBK modelling-facilitated reverse dosimetry of in vitro toxicity data obtained in the ES-D3 cell differentiation assay. Furthermore, it was investigated whether the ES-D3 differentiation assay for developmental toxicity reflects the role of ERα in the mode of action underlying DES-induced adverse effects on development. To this end, the effect of DES in the ES-D3 cell differentiation assay in the presence or absence of the ERα antagonist fulvestrant was characterised, a PBK model for DES was developed and evaluated, and results obtained for the developmental toxicity of DES in vitro were translated to in vivo dose–response curves using PBK modelling-facilitated reverse dosimetry.

The previous studies demonstrated that PBK modelling-facilitated reverse dosimetry of data obtained in the ES-D3 cell differentiation assay of the EST could adequately predict developmental toxicity for glycol ethers, retinoic acid, a series of phenols, and tebuconazole (Li et al. 2017; Louisse et al. 2010, 2015, Strikwold et al. 2017). The results of the present study reveal that the approach cannot quantitatively predict the reported in vivo developmental toxicity of DES, since predicted dose–response curves appeared to occur at dose levels that were about three-to-four orders of magnitude higher than what is actually observed in vivo (Cornwall et al. 1984; Wardell et al. 1982). Comparison of the results for DES to those previously obtained for other developmental toxins reveals that DES deviates from the other toxins, in that the in vitro ES-D3 cell differentiation assay seems to be relatively less sensitive than what would be expected based on its in vivo developmental toxicity (Fig. 8a). In addition, when kinetics are taken into account, the predicted data for DES are three orders of magnitude out of line with what was observed for other developmental toxins (Fig. 8b). This deviation for DES might be due to the fact that the ES-D3 cell differentiation assay does not capture the full sensitivity of the developing organism underlying the developmental toxicity of DES in vivo. For DES, the ES-D3 differentiation assay appeared to capture some aspects of its developmental toxicity, since DES inhibited ES-D3 cell differentiation at non-cytotoxic concentrations, and there was a role for ERα in the underlying mode of action. The latter was shown by the fact that the ERα antagonist fulvestrant counteracted the in vitro developmental toxicity of DES in the ES-D3 cell differentiation assay. In spite of this, the ES-D3 cell differentiation assay did not provide a basis for an adequate PBK model-facilitated reverse dosimetry-based prediction of the in vivo developmental toxicity in a quantitative way. This may due to the fact that the ES-D3 cell differentiation assay captures only early stages of development, while the major adverse effects induced by DES may occur apparent only later during development, and/or that developmental stages affected by DES are not involved in the processes reflected in the ES-D3 cell differentiation of the EST. The inadequacy of the PBK model-facilitated reverse dosimetry approach to correctly predict the in vivo developmental toxicity of DES is likely due to the inability of the ES-D3 cell differentiation assay to display full sensitivity for DES-induced developmental toxicity. The PBK model adequately predicted reported in vivo DES blood concentrations upon dosing 0.0005, 0.005, and 0.05 mg/kg bw DES intravenously (Thompson and Klaassen 1985) and 4 mg/kg bw upon oral dosing (Ako 2011). The fact that DES deviates from the comparison of the EST BMC50 to the in vivo BMD10 for developmental toxicity (Fig. 8a) also when taking kinetics into account (Fig. 8b) corroborates this conclusion.

As concluded above, this is most likely due to the inability of the ES-D3 cell differentiation assay to fully reflect the in vivo developmental toxicity of DES. A possible explanation for this might be that, the ES-D3 cell differentiation assay lacks the complex biological system and the metabolic capacity of intact organisms (Spielmann et al. 2006). In addition, it is suitable only for the early developmental stages (Pera and Trounson 2004).

The results of the present study show that the ES-D3 differentiation assay was able to represent the role of ERα in the developmental toxicity of DES. Activation and disruption of the ERα pathway might contribute to disruption of embryonic development (Bondesson et al. 2015; Greco et al. 1993), and it has been reported that ERα is essential for DES-induced effects, including phenotypic changes in the reproductive tract (malformed reproductive tract) and alterations of the expression of genes that are involved in regulation of the embryonic development as measured in neonates that have been exposed prenatally and neonatally (Block et al. 2000; Couse et al. 2001; Couse and Korach 2004; Ma et al. 1998; Miller et al. 1998). However, other mechanisms may be involved, as well. Literature indicates that epigenetic changes could be one of the main modes of action of DES-induced adverse effects, which can be passed on to the next generations. It has been reported that the sons and daughters of women who were exposed in utero to DES also showed increased numbers of birth defects, showing transgenerational effects that may be epigenetically regulated (Titus-Ernstoff et al. 2010). Furthermore, the role of epigenetics in developmental toxicity of DES follows for example from the fact that it has been reported that female mice exposed to DES in utero had aberrant methylation in the promotor and intron of the hoxa10 gene, a gene of which an adequate expression is critical during embryonic development (Bromer et al. 2009). Possibly, adverse developmental effects which are mediated via epigenetic changes cannot be adequately captured by the ES-D3 cell differentiation assay. Moreover, there are other potential mechanisms of action proposed for teratogenic chemicals (Wani et al. 2017); for example, formation of reactive oxygen species (Parman et al. 1999), which may be captured by the ES-D3 cell differentiation assay, and inhibition of angiogenesis (D’Amato et al. 1994), which is not captured by the ES-D3 cell differentiation assay. Yamashita et al. 2013 reported that DES induces downregulation of the angiogenesis factors VEGFA (vascular endothelial growth factor) and ANGPT1 (angiopoitin 1) in neonates that have been exposed in utero (Yamashita et al. 2013). This may be another important mechanism underlying DES-induced developmental toxicity, which is not captured by the ES-D3 cell differentiation assay.

The fact that other than only ERα-mediated pathways contribute to DES-induced developmental toxicity is supported also by the fact that the endogenous estrogen 17β-estradiol (E2), also able to activate ERα, is not reported to be a developmental toxin in vivo and did not induce developmental toxicity in the ES-D3 cell differentiation assay (only effects were observed at cytotoxic concentrations; data presented in the Supplementary materials 4 Fig. 4.1. Further studies will be necessary to define the mode(s) of action underlying the developmental toxicity of DES and to what extent these modes of action are detected in the ES-D3 differentiation assay of the EST. With this knowledge, in vitro endpoints and readout parameters may be selected that cover these modes of action, to include these endpoints in a test battery for in vitro developmental toxicity testing, to also cover chemicals with a mode of action similar to that of DES.

Altogether, it is concluded that although it was shown that the EST assay detects the in vitro developmental toxicity of DES and an adequate PBK model for description of DES kinetics was developed, combining these in vitro and in silico approaches could not predict the in vivo developmental toxicity of DES in a quantitative way. The inability of the EST to fully reflect DES-mediated developmental toxicity hampers adequate translation from the in vitro to the in vivo situation, probably due to the fact that the ES-D3 cell differentiation assay does not reflect the full mode of action underlying DES-induced developmental toxicity.

References

Ako RA (2011) Pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics (PK/PD) of oral diethylstilbestrol (DES) in recurrent prostate cancer patients and of oral dissolving film (ODF)-DES in Rats. University of Houston, Houston

Block K, Kardana A, Igarashi P, Taylor HS (2000) In utero diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposure alters Hox gene expression in the developing mullerian system. FASEB J 14(9):1101–1108

Bondesson M, Hao R, Lin CY, Williams C, Gustafsson JA (2015) Estrogen receptor signaling during vertebrate development. Biochim Biophys Acta 1849(2):142–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.06.005

Bromer JG, Wu J, Zhou Y, Taylor HS (2009) Hypermethylation of homeobox A10 by in utero diethylstilbestrol exposure: an epigenetic mechanism for altered developmental programming. Endocrinology 150(7):3376–3382. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2009-0071

Brown RP, Delp MD, Lindstedt SL, Rhomberg LR, Beliles RP (1997) Physiological parameter values for physiologically based pharmacokinetic models. Toxicol Ind Health 13(4):407–484. https://doi.org/10.1177/074823379701300401

Chiu WA, Ginsberg GL (2011) Development and evaluation of a harmonized physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) model for perchloroethylene toxicokinetics in mice, rats, and humans. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 253(3):203–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.taap.2011.03.020

Cornwall GA, Carter MW, Bradshaw WS (1984) The relationship between prenatal lethality or fetal weight and intrauterine position in rats exposed to diethylstilbestrol, zeranol, 3,4,3′,4′-tetrachlorobiphenyl, or cadmium. Teratology 30(3):341–349. https://doi.org/10.1002/tera.1420300306

Couse JF, Korach KS (2004) Estrogen receptor-alpha mediates the detrimental effects of neonatal diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposure in the murine reproductive tract. Toxicology 205(1–2):55–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tox.2004.06.046

Couse JF, Dixon D, Yates M et al (2001) Estrogen receptor-alpha knockout mice exhibit resistance to the developmental effects of neonatal diethylstilbestrol exposure on the female reproductive tract. Dev Biol 238(2):224–238. https://doi.org/10.1006/dbio.2001.0413

D’Amato RJ, Loughnan MS, Flynn E, Folkman J (1994) Thalidomide is an inhibitor of angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91(9):4082–4085

de Jong E, Louisse J, Verwei M et al (2009) Relative developmental toxicity of glycol ether alkoxy acid metabolites in the embryonic stem cell test as compared with the in vivo potency of their parent compounds. Toxicol Sci 110(1):117–124. https://doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kfp083

DeJongh J, Verhaar HJ, Hermens JL (1997) A quantitative property-property relationship (QPPR) approach to estimate in vitro tissue-blood partition coefficients of organic chemicals in rats and humans. Arch Toxicol 72(1):17–25

Evans MV, Andersen ME (2000) Sensitivity analysis of a physiological model for 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD): assessing the impact of specific model parameters on sequestration in liver and fat in the rat. Toxicol Sci 54(1):71–80

Giusti RM, Iwamoto K, Hatch EE (1995) Diethylstilbestrol revisited: a review of the long-term health effects. Ann Intern Med 122(10):778–788

Greco TL, Duello TM, Gorski J (1993) Estrogen receptors, estradiol, and diethylstilbestrol in early development: the mouse as a model for the study of estrogen receptors and estrogen sensitivity in embryonic development of male and female reproductive tracts. Endocr Rev 14(1):59–71. https://doi.org/10.1210/edrv-14-1-59

Hou TJ, Zhang W, Xia K, Qiao XB, Xu XJ (2004) ADME evaluation in drug discovery. 5. Correlation of Caco-2 permeation with simple molecular properties. J Chem Inf Comput Sci 44(5):1585–1600. https://doi.org/10.1021/ci049884m

IARC (2012) A review of human carcinogens. Part A: Pharmaceuticals. IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, 100:1–403. PMID: 23189749

Korach KS, Chae K, Levy LA, Duax WL, Sarver PJ (1989) Diethylstilbestrol metabolites and analogs. Stereochemical probes for the estrogen receptor binding site. J Biol Chem 264(10):5642–5647

Li H, Rietjens IM, Louisse J et al (2015) Use of the ES-D3 cell differentiation assay, combined with the BeWo transport model, to predict relative in vivo developmental toxicity of antifungal compounds. Toxicol in vitro 29(2):320–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tiv.2014.11.012

Li H, Zhang M, Vervoort J, Rietjens IM, van Ravenzwaay B, Louisse J (2017) Use of physiologically based kinetic modeling-facilitated reverse dosimetry of in vitro toxicity data for prediction of in vivo developmental toxicity of tebuconazole in rats. Toxicol Lett 266:85–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxlet.2016.11.017

Louisse J, de Jong E, van de Sandt JJ et al (2010) The use of in vitro toxicity data and physiologically based kinetic modeling to predict dose-response curves for in vivo developmental toxicity of glycol ethers in rat and man. Toxicol Sci 118(2):470–484. https://doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kfq270

Louisse J, Gonen S, Rietjens IM, Verwei M (2011) Relative developmental toxicity potencies of retinoids in the embryonic stem cell test compared with their relative potencies in in vivo and two other in vitro assays for developmental toxicity. Toxicol Lett 203(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxlet.2011.02.012

Louisse J, Bosgra S, Blaauboer BJ, Rietjens IM, Verwei M (2015) Prediction of in vivo developmental toxicity of all-trans-retinoic acid based on in vitro toxicity data and in silico physiologically based kinetic modeling. Arch Toxicol 89(7):1135–1148. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00204-014-1289-4

Louisse J, Beekmann K, Rietjens IM (2017) Use of physiologically based kinetic modeling-based reverse dosimetry to predict in vivo toxicity from in vitro data. Chem Res Toxicol 30(1):114–125. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrestox.6b00302

Ma L, Benson GV, Lim H, Dey SK, Maas RL (1998) Abdominal B (AbdB) Hoxa genes: regulation in adult uterus by estrogen and progesterone and repression in mullerian duct by the synthetic estrogen diethylstilbestrol (DES). Dev Biol 197(2):141–154. https://doi.org/10.1006/dbio.1998.8907

Miller C, Degenhardt K, Sassoon DA (1998) Fetal exposure to DES results in de-regulation of Wnt7a during uterine morphogenesis. Nat Genet 20(3):228–230. https://doi.org/10.1038/3027

Nagao T, Yoshimura S (2009) Early embryonic losses in mice induced by diethylstilbestrol. Congenit Anom 49(4):269–273. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-4520.2009.00247.x

Obach RS (1999) Prediction of human clearance of twenty-nine drugs from hepatic microsomal intrinsic clearance data: an examination of in vitro half-life approach and nonspecific binding to microsomes. Drug Metab Dispos Biol Fate Chem 27(11):1350–1359

Parman T, Wiley MJ, Wells PG (1999) Free radical-mediated oxidative DNA damage in the mechanism of thalidomide teratogenicity. Nat Med 5(5):582–585. https://doi.org/10.1038/8466

Pera MF, Trounson AO (2004) Human embryonic stem cells: prospects for development. Development 131(22):5515–5525. https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.01451

Prins GS, Birch L, Couse JF, Choi I, Katzenellenbogen B, Korach KS (2001) Estrogen imprinting of the developing prostate gland is mediated through stromal estrogen receptor alpha: studies with alphaERKO and betaERKO mice. Can Res 61(16):6089–6097

Roy D, Bernhardt A, Strobel HW, Liehr JG (1992) Catalysis of the oxidation of steroid and stilbene estrogens to estrogen quinone metabolites by the beta-naphthoflavone-inducible cytochrome P450 IA family. Arch Biochem Biophys 296(2):450–456

Selassie CD, Shusterman AJ, Kapur S, Verma RP, Zhang LT, Hansch C (1999) On the toxicity of phenols to fast growing cells. A QSAR model for a radical-based toxicity. J Chem Soc Perk T 2(12):2729–2733. https://doi.org/10.1039/a905764a

Sjogren E, Lennernas H, Andersson TB, Grasjo J, Bredberg U (2009) The multiple depletion curves method provides accurate estimates of intrinsic clearance (CLint), maximum velocity of the metabolic reaction (Vmax), and Michaelis constant (Km): accuracy and robustness evaluated through experimental data and Monte Carlo simulations. Drug Metab Dispos 37(1):47–58. https://doi.org/10.1124/dmd.108.021477

Slob W (2018) PROAST: software for dose–response modeling and benchmark dose analysis. RIVM. http://www.rivm.nl/en/Library/Scientific/Models/PROAST

Spielmann H, Seiler A, Bremer S, et al (2006) The practical application of three validated in vitro embryotoxicity tests. The report and recommendations of an ECVAM/ZEBET workshop (ECVAM workshop 57). Alternatives to laboratory animals: ATLA 34(5):527–538

Strikwold M, Spenkelink B, Woutersen RA, Rietjens IM, Punt A (2013) Combining in vitro embryotoxicity data with physiologically based kinetic (PBK) modelling to define in vivo dose-response curves for developmental toxicity of phenol in rat and human. Arch Toxicol 87(9):1709–1723. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00204-013-1107-4

Strikwold M, Spenkelink B, de Haan LHJ, Woutersen RA, Punt A, Rietjens I (2017) Integrating in vitro data and physiologically based kinetic (PBK) modelling to assess the in vivo potential developmental toxicity of a series of phenols. Arch Toxicol 91(5):2119–2133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00204-016-1881-x

Sun D, Lennernas H, Welage LS et al (2002) Comparison of human duodenum and Caco-2 gene expression profiles for 12,000 gene sequences tags and correlation with permeability of 26 drugs. Pharm Res 19(10):1400–1416

Thompson TN, Klaassen CD (1985) Hepatic presystemic elimination of diethylstilbestrol by rats and effect of pretreatment with inducers of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase. J Toxicol Environ Health 16(3–4):615–629. https://doi.org/10.1080/15287398509530768

Titus-Ernstoff L, Troisi R, Hatch EE et al (2010) Birth defects in the sons and daughters of women who were exposed in utero to diethylstilbestrol (DES). Int J Androl 33(2):377–384. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2605.2009.01010.x

van Liempd S, Morrison D, Sysmans L, Nelis P, Mortishire-Smith R (2011) Development and validation of a higher-throughput equilibrium dialysis assay for plasma protein binding. J Lab Autom 16(1):56–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jala.2010.06.002

Wakeling AE, Dukes M, Bowler J (1991) A potent specific pure antiestrogen with clinical potential. Can Res 51(15):3867–3873

Wani TH, Chakrabarty A, Shibata N, Yamazaki H, Guengerich FP, Chowdhury G (2017) The dihydroxy metabolite of the teratogen thalidomide causes oxidative DNA damage. Chem Res Toxicol 30(8):1622–1628. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrestox.7b00127

Wardell RE, Seegmiller RE, Bradshaw WS (1982) Induction of prenatal toxicity in the rat by diethylstilbestrol, zeranol, 3,4,3′,4′,-tetrachlorobiphenyl, cadmium, and lead. Teratology 26(3):229–237. https://doi.org/10.1002/tera.1420260303

Waters NJ, Jones R, Williams G, Sohal B (2008) Validation of a rapid equilibrium dialysis approach for the measurement of plasma protein binding. J Pharm Sci 97(10):4586–4595. https://doi.org/10.1002/jps.21317

Weir HM, Bradbury RH, Lawson M et al (2016) AZD9496: an oral estrogen receptor inhibitor that blocks the growth of ER-positive and ESR1-mutant breast tumors in preclinical models. Can Res 76(11):3307–3318. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2357

Yamashita S, Kudo A, Kawakami H, Okada Y (2013) Mechanisms of angiogenic suppression in uteri exposed to diethylstilbestrol neonatally in the mouse. Biol Reprod 88(5):116. https://doi.org/10.1095/biolreprod.112.106443

Zhang M, van Ravenzwaay B, Fabian E, Rietjens I, Louisse J (2018) Towards a generic physiologically based kinetic model to predict in vivo uterotrophic responses in rats by reverse dosimetry of in vitro estrogenicity data. Arch Toxicol 92(3):1075–1088. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00204-017-2140-5

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Wageningen University and BASF SE.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Adam, A.H.B., Zhang, M., de Haan, L.H.J. et al. The in vivo developmental toxicity of diethylstilbestrol (DES) in rat evaluated by an alternative testing strategy. Arch Toxicol 93, 2021–2033 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00204-019-02487-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00204-019-02487-6