Abstract

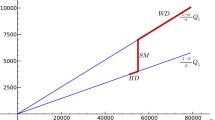

We use a comprehensive model of strategic household behavior in which the spouses’ expenditure on each public good is decomposed into autonomous spending and coordinated spending à la Lindahl. We obtain a continuum of semi-cooperative regimes parameterized by the relative weights put on autonomous spending, by each spouse and for each public good, nesting full cooperative and noncooperative regimes as limit cases. Testing is approached through revealed preference analysis, by looking for rationalizability of observed data sets, with the price of each public good lying between the maximum and the sum of the hypothesized marginal willingness to pay of the two spouses. Once rationalized, an observed data set always allows to identify the sharing rule, except when both spouses contribute in full autonomy to some public good (a situation of local income pooling).

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

d’Aspremont and Dos Santos Ferreira (2014).

Each individual is assumed to have a (personal) Bergson–Samuelson Social Welfare Function (SWF) through which she/he “cares” about the utility of each member in her/his household. This is in contrast with Samuelson (1956) consensus model where all members care and have the same SWF and with Becker (1974) where only one member (say the husband) cares. By varying the degree of intrahousehold caring for each individual member, Cherchye et al. (2015) also obtain a continuum of household consumption models between the fully cooperative model and the fully noncooperative model without caring.

Cherchye et al. (2015) have already shown that the sharing rule is identifiable for fully cooperative-rationalized data sets and not for noncooperative-rationalized data sets. Sharing rule identifiability also fails in models with caring, except when full cooperation is rationalized (Cherchye et al. 2015).

Suppose \(g_{k}^{B}=0\) and \(g_{k}^{A}>0\). Since \( Q_{k}^{A}=g_{k}^{A}+g_{k}^{B} \), \(\left( \left( Q_{k}^{A}-g_{k}^{A}\right) /Q_{k}^{A}\right) P_{k}=0\). This cannot be optimal as \(U^{B}\left( q^{B},Q^{B}\right) \) would increase if \(g_{k}^{B}\) (and \(Q_{k}^{B}\)) is increased (for free).

The initial marriage agreement could be viewed as the result of a preliminary stage where each spouse J chooses strategically the degrees of autonomy \(\theta _{k}^{J}\) for all k. This creates a moral hazard problem for the Lindahl mechanism since \(\theta \) identically zero may not be the equilibrium strategy of the first-stage game, although some other arrangement, with positive \(\theta \), may well be implementable. If there is incomplete information, efficiency may be even more difficult to reach (see Gori and Villanacci 2011).

As stated in d’Aspremont and Dos Santos Ferreira (2014, Proposition 2), the outcome of any \(\theta \)-equilibrium with separate spheres ( i.e., with \(g_{k}^{A}g_{k}^{B}=0\) for any public good k) coincides, even for \(\left( \theta ^{A},\theta ^{B}\right) \ne \left( 1,1\right) \), with the outcome of an equilibrium of the game with voluntary contributions to public goods.

One possible way of tackling this problem would be to use the exclusivity assumption suggested by Chiappori and Ekeland (2009), “whereby each member is the exclusive consumer of at least one good.”

Of course, rationalizability of any kind may also fail, as it can be easily shown using Example 1 in Cherchye et al. (2007).

For an application to the sharing rule recovery in the collective model along these lines, see Cherchye et al. (2011).

We have used Gusek software, which combines the SCIntilla based Text Editor (SciTE) plus the linear/integer programming solver GNU Linear Programming Kit (GLPK).

References

Becker, G.: A theory of social interactions. J. Polit. Econ. 82, 1063–1093 (1974)

Browning, M., Chiappori, P.-A.: Efficient intra-household allocations: a general characterisation and empirical tests. Econometrica 66, 1241–1278 (1998)

Browning, M., Chiappori, P.-A., Lechene, V.: Distributional effects in household models: separate spheres and income pooling. Econ. J. 120, 786–799 (2010)

Chen, Z., Woolley, F.: A Cournot-Nash model of family decision making. Econ. J. 111, 722–748 (2001)

Cherchye, L., Cosaertz, S., Demuynck, T., De Rock, B.: Noncooperative household consumption with caring, KU Leuven, Center for Economic Studies DPS15.29 (2015)

Cherchye, L., Demuynck, T., De Rock, B.: Revealed preference analysis of non-cooperative household consumption. Econ. J. 121, 1073–1096 (2011)

Cherchye, L., De Rock, B., Vermeulen, F.: The collective model of household consumption: a nonparametric characterization. Econometrica 75, 553–574 (2007)

Chiappori, P.-A.: Rational household labor supply. Econometrica 56, 63–90 (1988)

Chiappori, P.-A.: Collective labor supply and welfare. J. Polit. Econ. 100, 437–46 (1992)

Chiappori, P.-A., Ekeland, I.: The microeconomics of efficient group behavior: identification. Econometrica 77, 763–799 (2009)

d’Aspremont, C., Dos Santos Ferreira, R.: Household behavior and individual autonomy: an extended Lindahl mechanism. Econ. Theory 55, 643–664 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00199-013-0763-1

Donni, O.: Contribution 6.154.9. Household Behavior and Family Economics, in Mathematical models in Economics, vol. 1, The Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS) (2007)

Gori, M., Villanacci, A.: A bargaining model in general equilibrium. Econ. Theory 46, 327–375 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00199-009-0515-4

Hurwicz, L.: Outcome functions yielding Walrasian and Lindahl allocations at Nash equilibrium points. Rev. Econ. Stud. 46, 217–225 (1979)

Lechene, V., Preston, I.: Household Nash equilibrium with voluntarily contributed public goods. Econ Series WP 226, Oxford, (2005)

Lechene, V., Preston, I.: Noncooperative household demand. J. Econ. Theory 146, 504–527 (2011)

Lundberg, S., Pollak, R.A.: Separate spheres bargaining and the marriage market. J. Polit. Econ. 101, 988–1010 (1993)

Manser, M., Brown, M.: Marriage and household decision-making: a bargaining analysis. Intern. Econ. Rev. 21, 31–44 (1980)

McElroy, M.B., Horney, M.J.: Nash-bargained household decisions: toward a generalization of the theory of demand. Intern. Econ. Rev. 22, 333–349 (1981)

Samuelson, P.A.: Social indifference curves. Q. J. Econ. 70, 1–22 (1956)

Ulph, D.: A general non-cooperative Nash model of household consumption behavior. University of Bristol, Economics Discussion Paper 88/205, 1988. French translation: Un modèle non-coopératif de consommation des m énages. L’Actualité économique 82, 53–85 (2006)

Varian, H.: The nonparametric approach to demand analysis. Econometrica 50, 945–973 (1982)

Vermeulen, F.: Collective household models: principles and main results’. J. Econ. Surv. 16, 533–564 (2002)

Walker, M.: A simple incentive compatible scheme for attaining Lindahl allocations. Econometrica 49, 65–71 (1981)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

CORE is affiliated to ECORES.

This work was supported by the ANR FamPol project, grant ANR-14-FRAL-0007 of the French Agence Nationale de la Recherche.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

d’Aspremont, C., Dos Santos Ferreira, R. Enlarging the collective model of household behavior: A revealed preference analysis. Econ Theory 68, 1–19 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00199-018-1110-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00199-018-1110-3

Keywords

- Semi-cooperative household behavior

- Revealed preference analysis

- Rationalizability

- Sharing rule identification