Abstract

Summary

Among 4238 cancer and 16,418 cancer-free individuals with incident major non-traumatic fractures (hip, clinical vertebral, forearm, humerus), post-fracture osteoporosis care was equally poor for both groups, whether assessed from bone mineral density (BMD) testing, initiation of osteoporosis therapy or either intervention (BMD testing and/or osteoporosis therapy).

Introduction

Most individuals sustaining a fracture do not undergo evaluation and/or treatment for osteoporosis. Cancer survivors are at increased risk for osteoporosis and fracture. Whether cancer survivors experience a similar post-fracture “care gap” is unclear. Using population-based databases, we assessed whether cancer patients are evaluated and/or treated for osteoporosis after a major fracture.

Methods

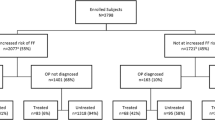

From the Manitoba Cancer Registry, we identified cancer cases (first cancer diagnosis between 1987 and 2013) and cancer-free controls with incident major non-traumatic fractures (from provincial physician billing claims and hospitalization databases). The outcomes were performance of BMD testing (from the BMD Registry), initiation of osteoporosis therapy (from drug dispensation database) or either intervention (BMD testing and/or osteoporosis therapy) in the 12 months post-fracture.

Results

There were 4238 cancer and 16,418 cancer-free individuals who sustained a fracture after the index date (cancer diagnosis) and were followed for at least 1 year post-fracture. Subsequent BMD testing was performed in 11.0% of cancer cases versus 11.5% non-cancer controls (P = 0.43), osteoporosis treatment in 22.9% cancer cases versus 21.8% non-cancer controls (P = 0.15), and either testing or treatment in 28.9% cancer cases versus 28.4% non-cancer controls (P = 0.53). Predictors of BMD testing and/or initiation of therapy were similar for non-cancer and cancer patients. Post-fracture interventions were consistently used more frequently among women, older patients (age 50 years or older), those who sustained fractures in a later calendar period, and (for treatment) after vertebral fracture. Cancer-specific variables (cancer type, years from cancer diagnosis to fracture, specialty of care provider) showed only weak and inconsistent effects.

Conclusions

A large care gap exists among cancer patients who sustain a fracture, similar to the general population, whereby the evaluation or treatment for osteoporosis is seldom conducted. Care maps may need to be developed for cancer populations to improve post-fracture care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

No additional data available.

References

Compston JE, McClung MR, Leslie WD (2019) Osteoporosis. Lancet. 393(10169):364–376

Levis S, Theodore G (2012) Summary of AHRQ's comparative effectiveness review of treatment to prevent fractures in men and women with low bone density or osteoporosis: update of the 2007 report. J Manag Care Pharm 18(4 Suppl B):S1–S15 discussion S3

Murad MH, Drake MT, Mullan RJ, Mauck KF, Stuart LM, Lane MA et al (2012) Clinical review. Comparative effectiveness of drug treatments to prevent fragility fractures: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97(6):1871–1880

Saito T, Sterbenz JM, Malay S, Zhong L, MacEachern MP, Chung KC (2017) Effectiveness of anti-osteoporotic drugs to prevent secondary fragility fractures: systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 28(12):3289–3300

Kanis JA, Johnell O, De Laet C, Johansson H, Oden A, Delmas P et al (2004) A meta-analysis of previous fracture and subsequent fracture risk. Bone. 35(2):375–382

Papaioannou A, Morin S, Cheung AM, Atkinson S, Brown JP, Feldman S et al (2010) 2010 clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in Canada: summary. CMAJ. 182(17):1864–1873

Kanis JA, Cooper C, Rizzoli R, Reginster JY, Scientific Advisory Board of the European Society for Clinical Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis and the Committees of Scientific Advisors and National Societies of the International Osteoporosis Foundation. Executive summary of European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2019.

Compston J, Cooper A, Cooper C, Gittoes N, Gregson C, Harvey N et al (2017) UK clinical guideline for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Arch Osteoporos 12(1):43

Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, Lewiecki EM, Tanner B, Randall S et al (2014) Clinician's guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 25(10):2359–2381

Little EA, Eccles MP (2010) A systematic review of the effectiveness of interventions to improve post-fracture investigation and management of patients at risk of osteoporosis. Implement Sci 5:80

Khosla S, Cauley JA, Compston J, Kiel DP, Rosen C, Saag KG et al (2017) Addressing the crisis in the treatment of osteoporosis: a path forward. J Bone Miner Res 32(3):424–430

Conley RB, Adib G, Adler RA, Akesson KE, Alexander IM, Amenta KC et al (2020) Secondary fracture prevention: consensus clinical recommendations from a multistakeholder coalition. J Bone Miner Res 35(1):36–52

Shapiro CL, Van Poznak C, Lacchetti C, Kirshner J, Eastell R, Gagel R et al (2019) Management of osteoporosis in survivors of adult cancers with nonmetastatic disease: ASCO clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol 37(31):2916–2946

Roos NP, Shapiro E (1999) Revisiting the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy and Evaluation and its population-based health information system. Med Care 37(6 Suppl):JS10–JJS4

Kozyrskyj AL, Mustard CA (1998) Validation of an electronic, population-based prescription database. Ann Pharmacother 32(11):1152–1157

Metge C, Black C, Peterson S, Kozyrskyj AL (1999) The population's use of pharmaceuticals. Med Care 37(6 Suppl):JS42–JS59

Tucker T, Howe H, Weir H (1999) Certification for population-based cancer registries. J Reg Mgmt 26(1):24–27

Leslie WD, Metge C (2003) Establishing a regional bone density program: lessons from the Manitoba experience. J Clin Densitom 6(3):275–282

Leslie WD, Caetano PA, Macwilliam LR, Finlayson GS (2005) Construction and validation of a population-based bone densitometry database. J Clin Densitom 8(1):25–30

Manitoba Centre for Health Policy. Concept: Regional Health Authority (RHA) Districts and Zones in Manitoba. 2013. Available from: http://mchp-appserv.cpe.umanitoba.ca/viewConcept.php?printer=Y&conceptID=1219 (Last accessed January 12, 2020).

Lix LM, Azimaee M, Osman BA, Caetano P, Morin S, Metge C et al (2012) Osteoporosis-related fracture case definitions for population-based administrative data. BMC Public Health 12:301

Epp R, Alhrbi M, Ward L, Leslie WD (2018) Radiological validation of fracture definitions from administrative data. J Bone Miner Res 33(Supp 1):S275

O'Donnell S, Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System Osteoporosis Working G (2013) Use of administrative data for national surveillance of osteoporosis and related fractures in Canada: results from a feasibility study. Arch Osteoporos 8:143

Curtis JR, Taylor AJ, Matthews RS, Ray MN, Becker DJ, Gary LC et al (2009) "Pathologic" fractures: should these be included in epidemiologic studies of osteoporotic fractures? Osteoporos Int 20(11):1969–1972

Chateau D, Metge C, Prior H, Soodeen RA (2012) Learning from the census: the Socio-economic Factor Index (SEFI) and health outcomes in Manitoba. Can J Public Health 103(8 Suppl 2):S23–S27

Damji AN, Bies K, Alibhai SM, Jones JM (2015) Bone health management in men undergoing ADT: examining enablers and barriers to care. Osteoporos Int 26(3):951–959

Van Tongeren LS, Duncan GG, Kendler DL, Pai H (2009) Implementation of osteoporosis screening guidelines in prostate cancer patients on androgen ablation. J Clin Densitom 12(3):287–291

Demeter S, Reed M, Lix L, MacWilliam L, Leslie WD (2005) Socioeconomic status and the utilization of diagnostic imaging in an urban setting. CMAJ. 173(10):1173–1177

Demeter S, Leslie WD, Lix L, MacWilliam L, Finlayson GS, Reed M (2007) The effect of socioeconomic status on bone density testing in a public health-care system. Osteoporos Int 18(2):153–158

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy for use of data contained in the Manitoba Population Research Data Repository (2015/2016-10). The results and conclusions are those of the authors and no official endorsement by the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy, Manitoba Health, Seniors and Active Living, or other data providers is intended or should be inferred. This article has been reviewed and approved by the members of the Manitoba Bone Density Program Committee. LML is supported by a Tier I Canada Research Chair.

Funding

This study was funded through a Research Operating Grant from the CancerCare Manitoba Foundation (grant # 763045126).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of the University of Manitoba and the Health Information Privacy Committee of Manitoba Health.

Conflicts of interest

William Leslie, Beatrice Edwards, Saeed Al-Azazi, Lin Yan, Lisa Lix, and Piotr Czaykowski declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Harminder Singh has been on advisory board of Takeda Canada, Pendopharm, Ferring Merck Canada and Guardant Health, Inc., has received an educational grant from Ferring and research funding from Merck Canada.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 14 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Leslie, W.D., Edwards, B., Al-Azazi, S. et al. Cancer patients with fractures are rarely assessed or treated for osteoporosis: a population-based study. Osteoporos Int 32, 333–341 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-020-05596-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-020-05596-6