Abstract

Summary

We evaluated the prevalence of osteoporosis using the osteoporosis diagnostic criteria developed by the National Bone Health Alliance (NBHA), which includes qualified fractures, FRAX score in addition to bone mineral density (BMD). The expanded definition increases the prevalence compared to BMD alone definitions; however, it may better identify those at elevated fracture risk.

Purpose

The purpose of this paper is to estimate the prevalence of osteoporosis in US adults ≥50 years using the NBHA osteoporosis diagnostic criteria.

Methods

Utilizing 2005–2008 data of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), we identified participants with osteoporosis with any one of the following: (1) femoral neck or lumbar spine T-score ≤ −2.5; (2) low trauma hip fracture irrespective of BMD or clinical vertebral, proximal humerus, pelvis, or distal forearm fracture with a T-score >−2.5 <−1.0; or (3) FRAX score at the National Osteoporosis Foundation intervention thresholds (≥3% for hip fracture or ≥20% for major osteoporotic fracture). We estimated the prevalence overall and by gender and age.

Results

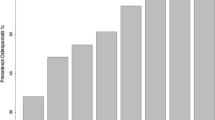

Our sample included 1948 (54.3%) men and 1639 (45.7%) women. Approximately 12% were 80+ years and 21% were from racial/ethnic minority groups. We estimated that 16.0% (0.8) of men and 29.9% (1.0) of women 50+ years have osteoporosis. The prevalence increases with age to 46.3% in men and 77.1% in women 80+ years. The combination of FRAX score and fractures was the largest contributing factor defining osteoporosis in men (70–79, 88.1%; 80+, 80.1%), whereas T-score was the largest contributing factor in women (70–79, 49.2%; 80+, 43.5%).

Conclusions

We found that 16% of men and 29.9% of women 50+ have osteoporosis based on the NBHA diagnostic criteria. Although the expanded definition increases the prevalence compared to BMD alone-based definitions, it may better identify those at elevated fracture risk in order to reduce the burden of fractures in older adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

(2000) Osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. NIH Conses Statement 17(1):1–45

Wright NC, Looker AC, Saag KG, Curtis JR, Delzell ES, Randall S et al (2014) The recent prevalence of osteoporosis and low bone mass in the United States based on bone mineral density at the femoral neck or lumbar spine. J Bone Miner Res 29(11):2520–2526. doi:10.1002/jbmr.2269

Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, Lewiecki EM, Tanner B, Randall S et al (2014) Clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 25(10):2359–2381. doi:10.1007/s00198-014-2794-2

Kanis JA, Burlet N, Cooper C, Delmas PD, Reginster JY, Borgstrom F et al (2008) European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 19(4):399–428. doi:10.1007/s00198-008-0560-z

Kanis JA, WHOSG (2007) Assessment of osteoporosis at the primary health-care level. University of Sheffield, World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Metabolic Bone Diseases

Office of the Surgeon General (U.S.) (2014) Department of Health and Human Services. Bone health and osteoporosis: a report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD. https://www.niams.nih.gov/Health_Info/Bone/SGR/SGRBoneHealthEnglish2015_022516.pdfhttps://www.niams.nih.gov/Health_Info/Bone/SGR/SGRBoneHealthEnglish2015_022516.pdf

Siris ES, Adler R, Bilezikian J, Bolognese M, Dawson-Hughes B, Favus MJ et al (2014) The clinical diagnosis of osteoporosis: a position statement from the National Bone Health Alliance Working Group. Osteoporos Int 25(5):1439–1443. doi:10.1007/s00198-014-2655-z

Zipf G CM, Porter KS, et al.. 2013 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: plan and operations, 1999–2010. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat;1(56)

Baim S, Binkley N, Bilezikian JP, Kendler DL, Hans DB, Lewiecki EM et al (2008) Official positions of the International Society for Clinical Densitometry and executive summary of the 2007 ISCD Position Development Conference. J Clin Densitom 11(1):75–91. doi:10.1016/j.jocd.2007.12.007S1094-6950(07)00255-7

Prevention CfDCa (1999-2011) National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Hyattsville

NCHS CfDCaP (2006) National Health and Nutrition Survey: body composition procedure manual. US Department of Health and Human Services, Hyattsville

NCHS CfDCaP (2007) National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) procedure manual. Hyattsville

Looker AC, Wahner HW, Dunn WL, Calvo MS, Harris TB, Heyse SP et al (1998) Updated data on proximal femur bone mineral levels of US adults. Osteoporos Int 8(5):468–489

Kelly T (1990) Bone mineral density reference databases for American men and women. J Bone Miner Res 5(Suppl1):S249

Kanis JA, Melton LJ 3rd, Christiansen C, Johnston CC, Khaltaev N (1994) The diagnosis of osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res 9(8):1137–1141. doi:10.1002/jbmr.5650090802

(2016) National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007–2008 data documentation, codebook, and frequencies: osteoporosis 2009. Available from: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2007-2008/OSQ_E.htm. Accessed 23 Nov 2016

Dawson-Hughes B, Looker AC, Tosteson AN, Johansson H, Kanis JA, Melton LJ 3rd (2012) The potential impact of the National Osteoporosis Foundation guidance on treatment eligibility in the USA: an update in NHANES 2005-2008. Osteoporos Int 23(3):811–820. doi:10.1007/s00198-011-1694-y

Looker AC, Melton LJ 3rd, Harris TB, Borrud LG, Shepherd JA (2010) Prevalence and trends in low femur bone density among older US adults: NHANES 2005-2006 compared with NHANES III. J Bone Miner Res 25(1):64–71. doi:10.1359/jbmr.090706

Schousboe JT, Ensrud KE (2015) Diagnostic criteria for osteoporosis should not be expanded. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 3(4):236–238. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00050-9S2213-8587(15)00050-9

Hillier TA, Cauley JA, Rizzo JH, Pedula KL, Ensrud KE, Bauer DC et al (2011) WHO absolute fracture risk models (FRAX): do clinical risk factors improve fracture prediction in older women without osteoporosis? J Bone Miner Res 26(8):1774–1782. doi:10.1002/jbmr.372

Schuit SC, van der Klift M, Weel AE, de Laet CE, Burger H, Seeman E et al (2004) Fracture incidence and association with bone mineral density in elderly men and women: the Rotterdam study. Bone 34(1):195–202

Siris ES, Chen YT, Abbott TA, Barrett-Connor E, Miller PD, Wehren LE et al (2004) Bone mineral density thresholds for pharmacological intervention to prevent fractures. Arch Intern Med 164(10):1108–1112. doi:10.1001/archinte.164.10.1108164/10/1108

Wainwright SA, Marshall LM, Ensrud KE, Cauley JA, Black DM, Hillier TA et al (2005) Hip fracture in women without osteoporosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90(5):2787–2793

Chen Z, Kooperberg C, Pettinger MB, Bassford T, Cauley JA, LaCroix AZ et al (2004) Validity of self-report for fractures among a multiethnic cohort of postmenopausal women: results from the Women’s Health Initiative observational study and clinical trials. Menopause 11(3):264–274

Fink HA, Milavetz DL, Palermo L, Nevitt MC, Cauley JA, Genant HK et al (2005) What proportion of incident radiographic vertebral deformities is clinically diagnosed and vice versa? J Bone Miner Res 20(7):1216–1222. doi:10.1359/JBMR.050314

Gehlbach S, Saag KG, Adachi JD, Hooven FH, Flahive J, Boonen S et al (2012) Previous fractures at multiple sites increase the risk for subsequent fractures: the global longitudinal study of osteoporosis in women. J Bone Miner Res 27(3):645–653. doi:10.1002/jbmr.1476

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Anne Looker, PhD, for her assistance with the provision and analysis of the NHANES data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Financial disclosures

NCW: research grants/contracts: Amgen.

KGS: consultant: Amgen, Lilly, Merck.

ESS: consultant: Amgen, Merck, Radius.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wright, N.C., Saag, K.G., Dawson-Hughes, B. et al. The impact of the new National Bone Health Alliance (NBHA) diagnostic criteria on the prevalence of osteoporosis in the USA. Osteoporos Int 28, 1225–1232 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-016-3865-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-016-3865-3