Abstract

Summary

The Veterans Affairs Spinal Cord Dysfunction Registry from 2002 to 2007 was reviewed to determine whether men with spinal cord injury (SCI) and lower extremity fractures had an increased risk of complications compared to those without fractures. We determined that fractures are associated with significant consequences, particularly during the first month postfracture.

Introduction

Despite increasing longevity, patients with SCI have a substantial number of illnesses and comorbid conditions. Lower extremity fractures are frequent events in these patients. However, whether these fractures are associated with any increased risk of complications in SCI is not certain. The purpose of this report was to determine the impact of lower extremity fractures on morbidities in men with SCI.

Methods

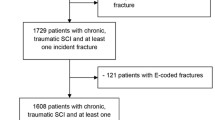

A population-based, nested, case–control (1,027 cases and 1,027 propensity-matched controls) of men enrolled in the Veterans Affairs Spinal Cord Dysfunction Registry from fiscal years 2002 to 2007 was reviewed to determine whether lower extremity fractures were associated with an increased risk for complications.

Results

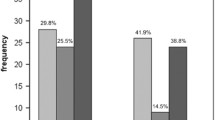

In propensity score models matched for demographic (age, race) and SCI-related injury factors (level/completeness of SCI), Veterans Affairs-service connection status, and comorbidities, at 1 month following the fracture, there was an increased risk for respiratory infections, pressure ulcers, urinary tract infections, thromboembolic events, depression, and delirium (p ≤ 0.03 for all). Over 12 months, the only complication more common in fracture cases was pressure ulcers (p < 0.01), with an absolute difference of less than 2 % when compared to controls. There was no significant increased risk of cardiac arrhythmias at any time examined following fracture (≥0.12).

Conclusions

Lower extremity fractures are associated with significant consequences in men with SCI during the first month postfracture, but they do not persist for a long term, except for pressure ulcers. Targeted interventions to prevent complications should be considered following lower extremity fractures in SCI, particularly in the first month following fracture.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Pages SCII. Spinal cord injury facts & statistics. [webpages]. Available from http://www.sci-info-pages.com/facts.html. Accessed 21 Nov 2012

Ragnarsson KT, Sell GH (1981) Lower extremity fractures after spinal cord injury: a retrospective study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 62(9):418–423

Freehafer AA, Hazel CM, Becker CL (1981) Lower extremity fractures in patients with spinal cord injury. Paraplegia 19(6):367–372

Ingram RR, Suman RK, Freeman PA (1989) Lower limb fractures in the chronic spinal cord injured patient. Paraplegia 27(2):133–139

Zehnder Y et al (2004) Long-term changes in bone metabolism, bone mineral density, quantitative ultrasound parameters, and fracture incidence after spinal cord injury: a cross-sectional observational study in 100 paraplegic men. Osteoporos Int 15(3):180–189

Frisbie JH (1997) Fractures after myelopathy: the risk quantified. J Spinal Cord Med 20(1):66–69

Nottage WM (1981) A review of long-bone fractures in patients with spinal cord injuries. Clin Orthop Relat Res 155:65–70

Lazo MG et al (2001) Osteoporosis and risk of fracture in men with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 39(4):208–214

Burns AS, O'Connell C (2012) The challenge of spinal cord injury care in the developing world. J Spinal Cord Med 35(1):3–8

Smith BM et al (2007) Acute respiratory tract infection visits of veterans with spinal cord injuries and disorders: rates, trends, and risk factors. J Spinal Cord Med 30(4):355–361

Weaver FM et al (2006) Outcomes of outpatient visits for acute respiratory illness in veterans with spinal cord injuries and disorders. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 85(9):718–726

Byrne DW, Salzberg CA (1996) Major risk factors for pressure ulcers in the spinal cord disabled: a literature review. Spinal Cord 34(5):255–263

Garcia Leoni ME, Esclarin De Ruz A (2003) Management of urinary tract infection in patients with spinal cord injuries. Clin Microbiol Infect 9(8):780–785

Kadyan V et al (2003) Surveillance with duplex ultrasound in traumatic spinal cord injury on initial admission to rehabilitation. J Spinal Cord Med 26(3):231–235

Elliott TR, Frank RG (1996) Depression following spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 77(8):816–823

Frank RG et al (1987) Differences in coping styles among persons with spinal cord injury: a cluster-analytic approach. J Consult Clin Psychol 55(5):727–731

Ravensbergen HJ et al (2012) Electrocardiogram-based predictors for arrhythmia after spinal cord injury. Clin Auton Res 22(6):265–273

Echigoya Y, Kato H (2008) Postoperative complications after femoral neck fracture in advanced elderly patients. Masui 57(2):163–166

Johnson EE, Kay RM, Dorey FJ (1994) Heterotopic ossification prophylaxis following operative treatment of acetabular fracture. Clin Orthop Relat Res 305:88–95

Merchant RA et al (2005) The relationship between postoperative complications and outcomes after hip fracture surgery. Ann Acad Med Singapore 34(2):163–168

Smith BM et al (2010) Using VA data for research in persons with spinal cord injuries and disorders: lessons from SCI QUERI. J Rehabil Res Dev 47(8):679–688

Logan WC Jr et al (2008) Incidence of fractures in a cohort of veterans with chronic multiple sclerosis or traumatic spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 89(2):237–243

Weaver FM et al (2008) Providing all-inclusive care for frail elderly veterans: evaluation of three models of care. J Am Geriatr Soc 56(2):345–353

Charlson ME et al (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 40(5):373–383

Mezuk B, Eaton WW, Golden SH (2008) Depression and osteoporosis: epidemiology and potential mediating pathways. Osteoporos Int 19(1):1–12

van den Berg M et al (2011) Depression after low-energy fracture in older women predicts future falls: a prospective observational study. BMC Geriatr 11:73

Hanlon JT et al (2011) Potential underuse, overuse, and inappropriate use of antidepressants in older veteran nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc 59(8):1412–1420

Quan H et al (2005) Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care 43(11):1130–1139

Morse LR et al (2009) Osteoporotic fractures and hospitalization risk in chronic spinal cord injury. Osteoporos Int 20(3):385–392

Monte-Secades R et al (2011) Risk factors for the development of medical complications in patients with hip fracture. Rev Calid Asist 26(2):76–82

Beaupre LA et al (2006) Reduced morbidity for elderly patients with a hip fracture after implementation of a perioperative evidence-based clinical pathway. Qual Saf Health Care 15(5):375–379

Anand S, Buch K (2007) Post-discharge symptomatic thromboembolic events in hip fracture patients. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 89(5):517–520

Mossey JM, Knott K, Craik R (1990) The effects of persistent depressive symptoms on hip fracture recovery. J Gerontol 45(5):M163–M168

Henzel MK et al (2011) Pressure ulcer management and research priorities for patients with spinal cord injury: consensus opinion from SCI QUERI Expert Panel on Pressure Ulcer Research Implementation. J Rehabil Res Dev 48(3):xi–xxxii

Evans CT et al (2010) Antibiotic prescribing for acute respiratory infection and subsequent outpatient and hospital utilization in veterans with spinal cord injury and disorder. PM & R J Inj Funct Rehabil 2(2):101–109

Teasell RW et al (2009) Venous thromboembolism after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 90(2):232–245

Peng CT et al (1998) Prolonged severe withdrawal symptoms after acute-on-chronic baclofen overdose. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol 36(4):359–363

Catic AG (2011) Identification and management of in-hospital drug-induced delirium in older patients. Drugs Aging 28(9):737–748

Montgomerie JZ (1997) Infections in patients with spinal cord injuries. Clin Infect Dis 25(6):1285–1290, quiz 1291-2

Evans CT et al (2008) Epidemiology of hospital-acquired infections in veterans with spinal cord injury and disorder. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 29(3):234–242

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Health Services Research and Development #IIR 08-033.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Carbone, L.D., Chin, A.S., Burns, S.P. et al. Morbidity following lower extremity fractures in men with spinal cord injury. Osteoporos Int 24, 2261–2267 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-013-2295-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-013-2295-8