Abstract

Summary

We determined whether suppression of sclerostin levels by estrogen treatment was mediated by anti-resorptive effect. Raloxifene, but not bisphosphonates, suppressed circulating sclerostin concentration, suggesting that sclerostin may mediate the action of estrogen on bone metabolism, independently of their anti-resorptive effects.

Introduction

Circulating sclerostin concentrations are higher in postmenopausal than in premenopausal women, and estrogen treatment suppresses sclerostin levels in both men and women. We determined whether anti-resorptives may suppress the circulating sclerostin levels.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective observational study. Eighty postmenopausal women were treated with raloxifene for 19.4 ± 7.7 months (n = 16), bisphosphonates for 19.2 ± 6.7 months (n = 32), or were untreated (n = 32) for 17.1 ± 4.6 months. Plasma sclerostin concentrations were measured before and after treatment.

Results

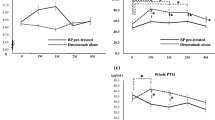

Plasma sclerostin levels after treatment were significantly lower in the raloxifene than in the control group (55.8 ± 23.4 pmol/l vs. 92.1 ± 50.4 pmol/l, p = 0.046), but were similar between the bisphosphonate and control groups. Relative to baseline, raloxifene treatment markedly reduced plasma sclerostin concentration (−40.7 ± 22.8%, p < 0.001), with respect to both control (−7.5 ± 29.1%) and bisphosphonate (−3.1 ± 35.2%) groups. Changes in bone-specific alkaline phosphatase and osteocalcin levels showed reverse associations with sclerostin concentration changes in the raloxifene (γ = −0.505, p = 0.017) and control (γ = −0.410, p = 0.020) groups.

Conclusions

Raloxifene, but not bisphosphonates, significantly suppressed circulating sclerostin concentration, suggesting that sclerostin may mediate the action of estrogen on bone metabolism, independently of their anti-resorptive effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Riggs BL, Khosla S, Melton LJ 3rd (2002) Sex steroids and the construction and conservation of the adult skeleton. Endocr Rev 23:279–302

Garnero P, Sornay-Rendu E, Chapuy MC, Delmas PD (1996) Increased bone turnover in late postmenopausal women is a major determinant of osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res 11:337–349

Bord S, Beavan S, Ireland D, Horner A, Compston JE (2001) Mechanisms by which high-dose estrogen therapy produces anabolic skeletal effects in postmenopausal women: role of locally produced growth factors. Bone 29:216–222

Khastgir G, Studd J, Holland N, Alaghband-Zadeh J, Fox S, Chow J (2001) Anabolic effect of estrogen replacement on bone in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: histomorphometric evidence in a longitudinal study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86:289–295

Semenov M, Tamai K, He X (2005) SOST is a ligand for LRP5/LRP6 and a Wnt signaling inhibitor. J Biol Chem 280:26770–26775

Glass DA 2nd, Bialek P, Ahn JD et al (2005) Canonical Wnt signaling in differentiated osteoblasts controls osteoclast differentiation. Dev Cell 8:751–764

Spencer GJ, Utting JC, Etheridge SL, Arnett TR, Genever PG (2006) Wnt signalling in osteoblasts regulates expression of the receptor activator of NFκB ligand and inhibits osteoclastogenesis in vitro. J Cell Sci 119:1283–1296

Winkler DG, Sutherland MK, Geoghegan JC et al (2003) Osteocyte control of bone formation via sclerostin, a novel BMP antagonist. EMBO J 22:6267–6276

Li X, Ominsky MS, Niu QT et al (2008) Targeted deletion of the sclerostin gene in mice results in increased bone formation and bone strength. J Bone Miner Res 23:860–869

Balemans W, Ebeling M, Patel N et al (2001) Increased bone density in sclerosteosis is due to the deficiency of a novel secreted protein (SOST). Hum Mol Genet 10:537–543

Balemans W, Patel N, Ebeling M et al (2002) Identification of a 52 kb deletion downstream of the SOST gene in patients with van Buchem disease. J Med Genet 39:91–97

Li X, Ominsky MS, Warmington KS et al (2009) Sclerostin antibody treatment increases bone formation, bone mass, and bone strength in a rat model of postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res 24:578–588

Padhi D, Jang G, Stouch B, Fang L, Posvar E (2011) Single-dose, placebo-controlled, randomized study of AMG 785, a sclerostin monoclonal antibody. J Bone Miner Res 26:19–26

Mirza FS, Padhi ID, Raisz LG, Lorenzo JA (2010) Serum sclerostin levels negatively correlate with parathyroid hormone levels and free estrogen index in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95:1991–1997

Modder UI, Clowes JA, Hoey K et al (2011) Regulation of circulating sclerostin levels by sex steroids in women and in men. J Bone Miner Res 26:27–34

Drake MT, Srinivasan B, Modder UI et al (2010) Effects of parathyroid hormone treatment on circulating sclerostin levels in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95:5056–5062

Paszty C, Turner CH, Robinson MK (2010) Sclerostin: a gem from the genome leads to bone building antibodies. J Bone Miner Res 25:1897–1904

Lane NE, Yao W (2010) Glucocorticoid-induced bone fragility. Ann New York Acad Sci 1192:81–83

Lopez-Ibarra PJ, Pastor MM, Escobar-Jimenez F et al (2001) Bone mineral density at time of clinical diagnosis of adult-onset type 1 diabetes mellitus. Endocr Pract 7:346–351

Dobnig H, Piswanger-Sölkner JC, Roth M et al (2006) Type 2 diabetes mellitus in nursing home patients: effects on bone turnover, bone mass, and fracture risk. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:3355–3363

Terpos E, Dimopoulos MA (2011) Interaction between the skeletal and immune systems in cancer: mechanisms and clinical implications. Canc Immunol Immunother 60:305–317

Mosekilde L (2008) Primary hyperparathyroidism and the skeleton. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 69:1–19

Vosse D, de Vlam K (2009) Osteoporosis in rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 27:S62–S67

Schindeler A, McDonald MM, Bokko P, Little DG (2008) Bone remodeling during fracture repair: the cellular picture. Semin Cell Dev Biol 19:459–466

Eastell R, Robins SP, Colwell T, Assiri AM, Riggs BL, Russell RG (1993) Evaluation of bone turnover in type I osteoporosis using biochemical markers specific for both bone formation and bone resorption. Osteoporos Int 3:255–260

Shang Y, Brown M (2002) Molecular determinants for the tissue specificity of SERMs. Science 295:2465–2468

Cremers S, Garnero P (2006) Biochemical markers of bone turnover in the clinical development of drugs for osteoporosis and metastatic bone disease: potential uses and pitfalls. Drugs 66:2031–2058

Leupin O, Kramer I, Collette NM et al (2007) Control of the SOST bone enhancer by PTH using MEF2 transcription factors. J Bone Miner Res 22:1957–1967

Modder UI, Hoey KA, Amin S et al (2011) Relation of age, gender, and bone mass to circulating sclerostin levels in women and men. J Bone Miner Res 26:373–379

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant of the Korea Healthcare Technology R&D Project, Ministry for Health, Welfare and Family Affairs, Republic of Korea. (Project no. A010252), a grant from the Korean Ministry of Education, Science & Technology (FPR08B1-170) of the 21C Frontier Functional Proteomics Program, and grants (2001–026, 2010–0354) from the Asan Institute for Life Sciences, Seoul, Korea.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Yun Ey Chung and Seung Hun Lee equally contributed to this work.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chung, Y.E., Lee, S.H., Lee, SY. et al. Long-term treatment with raloxifene, but not bisphosphonates, reduces circulating sclerostin levels in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 23, 1235–1243 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-011-1675-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-011-1675-1