Abstract

Summary

The Male Osteoporosis Assessment Questionnaire (OPAQ™) is a health-related quality of life (HRQOL) instrument that can differentiate between men with and without fracture. The Male OPAQ™ is a reliable and validated instrument that may be utilized in clinical trials seeking to include male populations.

Introduction

Men with osteoporosis (OP) experience poorer clinical outcomes than do women with the disorder, but little is known about the impact of OP on men’s HRQOL. This study aimed to test the validity, reliability, and ability to differentiate between men with and without fracture of an HRQOL for men with osteoporosis, the Male OPAQ™.

Methods

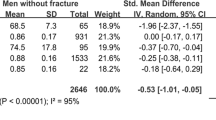

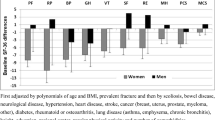

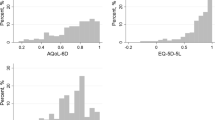

The OPAQ and OPAQ-SV were tested for face validity in interviews with male OP patients, and a revised, male-specific instrument was developed. Thirty-seven men ages 50+ completed the Male OPAQ™ and SF-12 at baseline and a two-week retest of the Male OPAQ™. To analyze both the domain and dimension scores, a normalization procedure was performed on the data to determine health status scores from 0 to 100. Descriptive statistics were calculated for each item and site. Reliability and validity of the Male OPAQ™ were assessed using Pearson’s r.

Results

The Male OPAQ™ can discriminate between men with and without fracture, and men who have more fractures have poorer scores. Instrument domains correspond to those of the SF-12.

Conclusions

The Male OPAQTM is a brief and sensitive tool for measuring HRQOL in men with OP. Further testing in a more diverse and large sample is warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

United States Department of Health and Human Services (2004) Bone health and osteoporosis: a report of the Surgeon General. Rickville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General

Cauley JA, Fullman RL, Stone KL, Zmuda JM, Bauer DC, Barrett-Connor E, Ensrud KE, Lau EMC, Orwoll ES (2005) Factors associated with the lumbar spine and proximal femur bone mineral density in older men. Osteoporos Int 16:1525–1537

Schousboe JT, Taylor BC, Fink HA, Kane RL, Cummings SR, Orwoll ES, Melton LJ, Bauer DC, Ensrud KE (2007) Cost-effectiveness of bone densitometry followed by treatment of osteoporosis in older men. JAMA 298(6):629–637

Michaelsson K, Olofsson H, Jensevik K, Larsson S, Mallmin H, Berglund L, Vessby B, Melhus H (2007) Leisure physical activity and the risk of fracture in men. PLoS Med 4(6):1094–1100

Solimeo S, Weber TJ, Gold DT (2011) Older men’s explanatory model for osteoporosis. Gerontologist. doi:10.1093/geront/gnq123

Solimeo S (2008) Osteoporosis in older men: feelings of masculinity and a “women’s disease”. Generations 32(1):73–77

Nguyen N, Ahlborg HG, Center JR, Eisman JA, Nguyen TV (2007) Residual lifetime risk of fractures in men and women. J Bone Miner Res 22(6):781–788

Cummings SR, Melton LJ (2002) Epidemiology and outcomes of osteoporotic fractures. Lancet 359(9319):1761–1767

Ebeling P (2008) Osteoporosis in men. N Engl J Med 358:1474–1482

Feldstein AC, Nichols G, Orwoll E (2004) The near absence of osteoporosis treatment in older men with fractures. Am J Manag Care 10(9):651–651

Johnson C, McLeod W, Kennedy L, McLeod K (2007) Osteoporosis health beliefs among younger and older men and women. Health Ed Behav 10(10):1–13

Ali NS, Shonk C, El-Sayed MS (2009) Bone health in men: influencing factors. Am J Health Behav 33(2):213–222

Guzman-Clark JR, Fang MA, Sehl ME, Traylor L, Hahn TJ (2007) Barriers in the management of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Arthritis Rhuem 57(1):140–146

Tosteson A, Hammond C (2002) Quality-of-life assessment in osteoporosis: health-status and preference-based measures. Pharmacoeconomics 20(5):289–303

Gold DT (2003) Osteoporosis and quality of life psychosocial outcomes and interventions for individual patients. Clin Geriatr Med 19(2):271–280

Gold DT (2001) The nonskeletal consequences of osteoporotic fractures: psychologic and social outcomes. Rheum Dis Clinic North Am 27(1):255–262

Gold DT (1996) The clinical impact of vertebral fractures: quality of life in women with osteoporosis. Bone 18(3 Suppl):s189–s194

Silverman SL, Minshall ME, Shen W, Harper KD, Xie S (2001) The relationship of health-related quality of life to prevalent and incident vertebral fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: results from the multiple outcomes of raloxifene evaluation study. Arthritis Rheum 44(1):2611–2619

Silverman SL (2000) The Osteoporosis Assessment Questionnaire (OPAQ): a reliable and valid disease-targeted measure of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in osteoporosis. Qual Life Res 9(6):767–774

Ware JE, Sherbourne CD (1992) The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36). Med Care 30(6):473–481

Randell AG, Nguyen TV, Bhalerao N, Silverman SL, Sambrook PN, Eisman JA (2000) Deterioration in quality of life following hip fracture: a prospective study. Osteoporos Int 11:460–466

Ware JE (1993) SF-36 Health Survey Manual and Interpretation Guide. The Health Institute, New England Medical Center, Boston

Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD (1996) A 12-item short-form health survey—construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 34(3):220–233

Calasanti T (2010) Gender relations and applied research on aging. Gerontologist 50(6):720–734

Cross, GM (2009) Under Secretary for health’s information letter: osteoporosis in men. Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Washington DC. IL 10-2009-009

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the men who participated in this study. Dr. Solimeo is currently a Health Research Scientist Specialist in the Center for Comprehensive Access and Delivery Research and Evaluation (CADRE) at the Iowa City VA Medical Center, which is funded through the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Health Services Research and Development Service. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government. The Center for the Study of Aging and Human Development at Duke University Medical Center provided facility support for Drs. Solimeo and Gold. Dr. Solimeo received institutional postdoctoral support for this research from The National Institute on Aging (5T32 AG00029-31). Dr. Silverman received support from the OMC Clinical Research Center, a California nonprofit. Drs. Gold and Solimeo thank Dr. Thomas J. Weber for his assistance with subject recruitment.

Conflicts of interest

SL Solimeo, PhD, MPH. No conflicts of interest to report.

SL Silverman, MD. Speaker’s Bureau: Lilly, Roche Pharmaceuticals, and Pfizer; Consultant: Warner Chilcott, Roche Pharmaceuticals, Roche Diagnostics, Novartis, Pfizer, and Lilly; Research Support: Lilly, Pfizer, and Alliance for Better Bone Health.

A Calderon, BS/BA. No conflicts of interest to report.

A Nguyen. No conflicts of interest to report.

DT Gold, PhD. Research funding: Novartis; Speaker Forum: Amgen, Eli Lilly & Co., Roche Diagnostics, sanofi-aventis; Consultant: Amgen, Eli Lilly & Co., Roche Diagnostics, sanofi-aventis; Board Member: Amgen, Eli Lilly & Co., Merck, Roche Diagnostics, sanofi-aventis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Male OPAQ™ version 1.1

Male OPAQ™ version 1.1

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Solimeo, S.L., Silverman, S.L., Calderon, A.D. et al. Measuring health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in osteoporotic males using the Male OPAQ. Osteoporos Int 23, 841–852 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-011-1625-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-011-1625-y