Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis

To describe complications at the time of surgery, 90-day readmission and 1-year reoperation rates after minimally invasive pelvic organ prolapse (POP) in women > 65 years of age in the US using Medicare 5% Limited Data Set (LDS) Files.

Methods

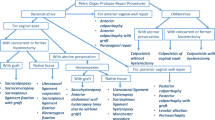

Medicare is a federally funded insurance program in the US for individuals 65 and older. Currently, 98% of individuals over the age of 65 in the US are covered by Medicare. We identified women undergoing minimally invasive POP surgery, defined as laparoscopic or vaginal surgery, in the inpatient and outpatient settings from 2011–2017. Patient and surgical characteristics as well as adverse events were abstracted. We used logistic regression for complications at index surgery and Cox proportional hazards regression models for time to readmission and time to reoperations.

Results

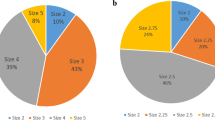

A total of 11,779 women met inclusion criteria. The mean age was 72 (SD ± 8) years; the majority were White (91%). Most procedures were vaginal (76%) and did not include hysterectomy (68%). The rate of complications was 12%; vaginal hysterectomy (aOR 2.4, 95% CI 2.2–2.7) was the factor most strongly associated with increased odds of complications. The 90-day readmission rate was 7.3%. The most common reason for readmission was infection (2.0%), three quarters of which were urinary tract infections. Medicaid eligibility (aHR 1.5, 95% CI 1.3–1.8) and concurrent sling procedures (aHR 1.2, 95% CI 1.04–1.4) were associated with a higher risk of 90-day readmission. The 1-year reoperation rate was 4.5%. The most common type of reoperation was a sling procedure (1.8%). Obliterative POP surgery (aHR 0.6, 95% CI 0.4–0.9) was associated with a lower risk of reoperation than other types of surgery.

Conclusions

US women 65 years and older who are also eligible to receive Medicaid are at higher risk of 90-day readmission following minimally invasive surgery for POP with the most common reason for readmission being UTI.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Nygaard I, Barber MD, Burgio KL, Kenton K, Meikle S, Schaffer J, Spino C, Whitehead WE, Wu J, Brody DJ, Pelvic Floor Disorders N. Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in US women. JAMA. 2008;300(11):1311–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.300.11.1311.

Wu JM, Hundley AF, Fulton RG, Myers ER. Forecasting the prevalence of pelvic floor disorders in US Women: 2010 to 2050. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(6):1278–83. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c2ce96.

Greer JA, Northington GM, Harvie HS, Segal S, Johnson JC, Arya LA. Functional status and postoperative morbidity in older women with prolapse. J Urol. 2013;190(3):948–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2013.03.004.

Vandendriessche D, Sussfeld J, Giraudet G, Lucot JP, Behal H, Cosson M. Complications and reoperations after laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy with a mean follow-up of 4 years. Int Urogynecol J. 2017;28(2):231–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-016-3093-6.

Mairesse S, Chazard E, Giraudet G, Cosson M, Bartolo S. Complications and reoperation after pelvic organ prolapse, impact of hysterectomy, surgical approach and surgeon experience. Int Urogynecol J. 2020;31(9):1755–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-019-04210-6.

Bretschneider CE, Nieto ML, Geller EJ, Palmer MH, Wu JM. The association of the Braden Scale Score and postoperative morbidity following urogynecologic surgery. Urol Nurs. 2016;36(4):191–7.

Clancy AA, Gauthier I, Ramirez FD, Hickling D, Pascali D. Predictors of sling revision after mid-urethral sling procedures: a case-control study. BJOG. 2019;126(3):419–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.15470.

Weltz V, Guldberg R, Larsen MD, Lose G. Body mass index influences the risk of reoperation after first-time surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. A Danish cohort study, 2010-2016. Int Urogynecol J. 2021;32(4):801–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-020-04482-3.

Ringel NE, de Winter KL, Siddique M, Marczak T, Kisby C, Rutledge E, Soriano A, Samimi P, Schroeder M, Handler S, Zeymo A, Gutman RE. Surgical outcomes in urogynecology-assessment of perioperative and postoperative complications relative to preoperative hemoglobin A1c-A Fellow's Pelvic Research Network Study. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1097/SPV.0000000000001057.

Dallas KB, Rogo-Gupta L, Elliott CS. What impacts the all cause risk of reoperation after pelvic organ prolapse repair? A comparison of mesh and native tissue approaches in 110,329 women. J Urol. 2018;200(2):389–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2018.02.3093.

Chughtai B, Barber MD, Mao J, Forde JC, Normand ST, Sedrakyan A. Association between the amount of vaginal mesh used with mesh erosions and repeated surgery after repairing pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(3):257–63. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2016.4200.

Pacquée S, Nawapun K, Claerhout F, Werbrouck E, Veldman J, D’hoore A, Wyndaele J, Verguts J, De Ridder D, Deprest J. Long-term assessment of a prospective cohort of patients undergoing laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134(2):323–32. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000003380.

Morling JR, McAllister DA, Agur W, Fischbacher CM, Glazener CM, Guerrero K, Hopkins L, Wood R. Adverse events after first, single, mesh and non-mesh surgical procedures for stress urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse in Scotland, 1997-2016: a population-based cohort study. Lancet. 2017;389(10069):629–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32572-7.

Malacarne Pape D, Escobar CM, Agrawal S, Rosenblum N, Brucker B. The impact of concomitant mid-urethral sling surgery on patients undergoing vaginal prolapse repair. Int Urogynecol J. 2021;32(3):681–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-020-04544-6.

Diwadkar GB, Barber MD, Feiner B, Maher C, Jelovsek JE. Complication and reoperation rates after apical vaginal prolapse surgical repair: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(2 Pt 1):367–73. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e318195888d.

Le Teuff I, Labaki M, Fabbro-Peray P, Debodinance P, Jacquetin B, Marty J, Letouzey V, Eglin G, de Tayrac R. Perioperative morbi-mortality after pelvic organ prolapse surgery in a large French national database from gynecologist surgeons. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2019;48(7):479–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogoh.2019.05.008.

Chughtai B, Mao J, Matheny ME, Mauer E, Banerjee S, Sedrakyan A. Long-term safety with sling mesh implants for stress incontinence. J Urol. 2021;205(1):183–90. https://doi.org/10.1097/ju.0000000000001312.

Sung VW, Rogers ML, Myers DL, Clark MA. Impact of hospital and surgeon volumes on outcomes following pelvic reconstructive surgery in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195(6):1778–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2006.07.015.

Mehta A, Xu T, Hutfless S, Makary MA, Sinno AK, Tanner EJ 3rd, Stone RL, Wang K, Fader AN. Patient, surgeon, and hospital disparities associated with benign hysterectomy approach and perioperative complications. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(5):497 e491–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2016.12.020.

Projected Future Growth of Older Population. 2019. https://acl.gov/aging-and-disability-in-america/data-and-research/projected-future-growth-older-population. Accessed April 10, 2022.

Dallas K, Dubinskaya A, Andebrhan SB, Anger J, Rogo-Gupta LJ, Elliott CS, Ackerman AL. Racial disparities in outcomes of women undergoing myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;138(6):845–51. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000004581.

Dällenbach P, Jungo Nancoz C, Eperon I, Dubuisson JB, Boulvain M. Incidence and risk factors for reoperation of surgically treated pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23(1):35–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-011-1483-3.

Brusselaers N, Lagergren J. The Charlson Comorbidity Index in registry-based research. Methods Inf Med. 2017;56(5):401–6. https://doi.org/10.3414/ME17-01-0051.

https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/eligibility/index.html. Accessed April 10, 2022.

Services CfMM. Global Surgery Booklet. 2018.

Dallas K, Elliott CS, Syan R, Sohlberg E, Enemchukwu E, Rogo-Gupta L. Association between concomitant hysterectomy and repeat surgery for pelvic organ prolapse repair in a cohort of nearly 100,000 women. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(6):1328–36. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000002913.

Erekson E, Murchison RL, Gerjevic KA, Meljen VT, Strohbehn K. Major postoperative complications following surgical procedures for pelvic organ prolapse: a secondary database analysis of the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217(5):608 e601–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2017.05.052.

Hokenstad ED, Glasgow AE, Habermann EB, Occhino JA. Readmission and reoperation after surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2017;23(2):131–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/SPV.0000000000000379.

Clancy AA, Chen I, Pascali D, Minassian VA. Surgical approach and unplanned readmission following pelvic organ prolapse surgery: a retrospective cohort study using data from the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Database (NSQIP). Int Urogynecol J. 2021;32(4):945–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-020-04505-z.

Sanaee MS, Pan K, Lee T, Koenig NA, Geoffrion R. Urinary tract infection after clean-contaminated pelvic surgery: a retrospective cohort study and prediction model. Int Urogynecol J. 2020;31(9):1821–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-019-04119-0.

Dallas KB, Trimble R, Rogo-Gupta L, Elliott CS. Care seeking patterns for women requiring a repeat pelvic organ prolapse surgery due to native tissue repair failure compared to a mesh complication. Urology. 2018;122:70–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2018.08.017.

Daugbjerg SB, Cesaroni G, Ottesen B, Diderichsen F, Osler M. Effect of socioeconomic position on patient outcome after hysterectomy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2014;93(9):926–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.12444.

Daugbjerg SB, Ottesen B, Diderichsen F, Frederiksen BL, Osler M. Socioeconomic factors may influence the surgical technique for benign hysterectomy. Dan Med J. 2012;59(6):A4440.

Dallas KB, Sohlberg EM, Elliott CS, Rogo-Gupta L, Enemchukwu E. Racial and socioeconomic disparities in short-term urethral sling surgical outcomes. Urology. 2017;110:70–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2017.08.021.

Sheyn D, Mahajan S, Billow M, Fleary A, Hayashi E, El-Nashar SA. Geographic variance of cost associated with hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(5):844–53. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000001966.

Financial support

NICHD R25-HD094667 AUGS/Duke UrogynCREST (Urogynecology Clinical Research Educational Scientist Training) program

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CEB: concept development, data analysis, manuscript writing and editing

CDS: concept development, manuscript writing and editing

OOP: data analysis, manuscript editing

DS: manuscript writing and editing

VS: concept development, manuscript writing and editing

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

Authors do not have any relevant disclosures. C.E.B. is a consultant for Boston Scientific. D.S. is a consultant for Renalis and receives research funding from NICHD.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

ESM 1

(DOCX 35 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bretschneider, C.E., Scales, C.D., Osazuwa-Peters, O. et al. Adverse outcomes after minimally invasive surgery for pelvic organ prolapse in women 65 years and older in the United States. Int Urogynecol J 33, 2409–2418 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-022-05238-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-022-05238-x