Abstract

The clinical impact of incontinence in pregnancy and after childbirth is growing because some studies report the efficacy of physiotherapy in pregnancy and because obstetric choices are supposed to have significant impact on post-reproductive urinary function (Goldberg et al. in Am J Obstet Gynecol 188:1447–1450, 2003). Thus, the need for objective measurement of urinary incontinence in pregnancy is growing. Data on pad testing in pregnancy are lacking. We assessed the clinical relevance of the 24-h pad test during pregnancy and after childbirth, compared with data on self-reported symptoms of urinary incontinence and visual analogue score. According to the receiver operating characteristic curve, the diagnostic value of pad testing for measuring (severity of) self-reported incontinence during pregnancy is not of clinical relevance. However, for the purposes of research, pad tests, combined with subjective/qualitative considerations, play a critical role in allowing comparisons across studies, quantifying the amount of urine loss and establishing a measure of severity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Incontinence is reported frequently in pregnancy and after childbirth [2–4]. It has been suggested that urinary incontinence in pregnancy is a predictor of the chance to develop post-partum urinary incontinence [5]. In that respect, prevention such as physiotherapy during pregnancy is advised in women with positive symptoms of urinary incontinence in pregnancy [6–9]. Based on questionnaires on symptoms of post-partum urinary incontinence, Goldberg et al. found a strong protective effect of cesarean delivery against the development of post-partum urinary incontinence and highlighted the impact of obstetric choices on post-reproductive urinary function [1]. When the possible consequences of the fact that a pregnant women reports urinary incontinence grow, such as an advise for preventive physiotherapy or an advice regarding the mode of delivery, there is a greater need for objectivity in diagnosing the problem. Pad testing yields an objective measurement of fluid loss over a certain period. In non-pregnant women, the diagnostic value of pad testing for self-reporting of symptoms of urinary incontinence has been questioned [10, 11]. These data are lacking for pregnant women. Most common used types of pad tests are the 1-h and the 24-h test [12–15]. The 24-h pad test is almost certainly more representative to the patients’ day-to-day experiences and is more likely to correlate with self-reported symptoms [16]. The 24-h pad testing has been studied and described exclusively in non-pregnant women. In this study, we focussed on the diagnostic strength of pad testing to measure (the severity of) urinary incontinence in pregnancy and after childbirth. The aims of this study were (1) to describe pad weight gain as measured by the 24-h pad test in a cohort of pregnant women and (2) to assess the clinical usefulness of the 24-h pad test in pregnancy and after childbirth in terms of the relationship between objective urine loss and the self-reported symptoms of urinary incontinence.

Materials and methods

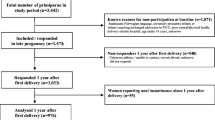

One hundred and seventeen women who attended the outpatient clinics of the University Hospital Groningen and the Martini Hospital Groningen enrolled for the study, with a mean age of 30 years (range 17–41). All women were of Caucasian origin, except three who were of Mediterranean origin. All women were nulliparous and had no history of incontinence, pelvic operations or neurological disease. Written informed consent was obtained from all participating women. The study was approved by the medical ethical committees of both hospitals. For this study, the women were investigated at 28–32 and at 36–38 weeks of pregnancy and 6 weeks and 6 months post-partum.

At each visit, all women completed a questionnaire and a visual analogue score (VAS) on symptoms of urinary incontinence. Complaints of more than five on the VAS scale 0–10 were defined as severe complaints. Women were asked to classify their incontinence as mainly: (1) stress urinary incontinence, involuntary leakage on effort or exertion or on sneezing or coughing, and (2) urge urinary incontinence, involuntary leakage accompanied by or immediately preceded by a strong desire to void [17]. Three pads were packed, each in a plastic bag, and weighed by the investigators before and after use. The women received a written instruction and were free to wear one, two or three pads. It was emphasised that the bag should be closed carefully every time a pad was changed to prevent evaporation. If the bags were open or less than three pads were returned, the test was excluded from evaluation. Pads were given to all women, to be worn for 24 h preceding their appointment. The outcome of the 24-h pad test was recorded as the weight gain as measured by a verified spring balance. Weighing was done by the first or second author, within 3 days after the pad test was carried out. According to the literature, pads were assigned as wet if the total weight gain per 24 h was ≥9 g [11].

Statistical analysis

Pad test results have a non-parametric distribution. For continuous variables, non-parametric tests are used. Numeric data are analysed by cross tabulation, chi-squared test and risk analysis. Pearson correlation test was used to identify significant relationships between variables. Data are presented as median or numbers.

Results

Pregnancy, pad test

At 28 weeks of pregnancy, 115 of 117 patients (98%) returned their pads according to the protocol. The median weight gain was 5 g (range 0–36). At 38 weeks, data were available from 98 women (84%). Two patients had withdrawn from the study because of inconvenience, while 17 pads were not, or were not according to the protocol returned. At this stage of pregnancy, the median weight gain was also 5 g (range 0–22). Distributions of pad test weight gain are given in Fig. 1.

Pad test results at 28 and 38 weeks of pregnancy were related (r = 0.452, p < 0.0001). Twenty-seven out of 115 (23%) and 17out of 98 pads (17%) were wet at 28 and 38 weeks of pregnancy, respectively, and again, results at 28 and 38 weeks were related (r = 0.317, p < 0.001).

Pregnancy, questionnaire

At 28 weeks of pregnancy, 35 of 117 women (30%) reported incontinence (stress, 28 of 35, and urge, 7 of 35), and at 38 weeks, 40 of 115 (35%) did (stress, 33 of 40 [82%], and urge, 7 of 40 [8%]). Reported incontinence at 28 and 38 weeks of pregnancy was related (r = 0.55, p < 0.001). Severe complaints of incontinence were reported in 17 of 117 (15%) and 22 of 115 cases (19%), which were also related (r = 0.482, p < 0.001).

Pregnancy, pad test and questionnaire

Women with self-reported incontinence at 28 and 38 weeks of pregnancy had a median pad weight gain of 6.0 (range 0–36) and 6.0 g (range 0–22), respectively, while women without self-reported incontinence had a pad test result of 4.0 (range 0–22) and 4.0 g (range 0–22), respectively, showing no differences between these groups of women. To evaluate the diagnostic value of the pad test for measuring self-reported incontinence, the sensitivity and specificity for several cutoff levels for the pad test was calculated, graphically known as the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. The ROC curve for pad tests and self-reported incontinence at 28 weeks of pregnancy did not differ from the reference line (area 0.575 vs 0.5, p = 0.207), showing a non-diagnostic test (Fig. 2). At 38 weeks of pregnancy, the ROC curve showed a significant difference from the reference line (area 0.663 vs 0.5, p = 0.008), the optimum cutoff point at 5.5 g with a sensitivity of 0.629 and a specificity of 0.619 (Fig. 2). When stratified for stress incontinence or for severe symptoms of urinary incontinence, the ROC curve did not improve.

Puerperium, pad test

At 6 weeks post-partum, 80 of 117 patients (68%) returned their pads according to the protocol. The median weight gain was 3 g (range 0–40). At 6 months post-partum, pad data were available from 76 patients (65%). Six patients had withdrawn from the study because of inconvenience, three patients had their delivery preterm, 32 pads were not, or were not according to the protocol returned. These women did not want to participate in the pad study anymore or did not return their pads according to the protocol. The women that withdrew from the pad test study were asked to fill up the questionnaires on symptoms of urinary incontinence to check for bias. The women did not differ for self-reported symptoms on urinary incontinence from the women that continued the study on pads. In the study group, the median weight gain was again 3 g (range 0–40). Distributions of the pad test weight gain are given in Fig. 3. Pad test results at 6 weeks and 6 months post-partum were related (r = 0.792, p < 0.0001). Seven out of 80 (9%) and 3 out of 76 pads (4%) were wet at 6 weeks and 6 months post-partum, respectively, and again, the results at 28 and 38 weeks were related (r = 0.320, p = 0.017).

Puerperium, questionnaire

At 6 weeks post-partum, 21 of 115 women (18%) reported incontinence (stress, 16 of 21, and urge, 5 of 21), while at 6 months post-partum, 16 of 109 (15%) did (stress, 12 of 16, and urge, 4 of 16). Reported incontinence at 6 weeks and 6 months post-partum is related (r = 0.61, p < 0.001). Severe complaints of incontinence was reported in 15 of 115 (13%) and 11 of 109 cases (10%), which were also related (r = 0.691, p < 0.001).

Puerperium, pad test and questionnaire

Women with self-reported incontinence at 6 weeks and 6 months post-partum had a median pad weight gain of 5.5 (range 0–40) and 6.0 g (range 0–40), respectively; women without self-reported incontinence had a pad test result of 3.0 (range 0–16) and 3.0 g (range 0–9), showing a differences between these groups of women (p = 0.01 and p = 0.045, respectively). The ROC curve for pad tests and self-reported incontinence at 6 weeks post differed from the reference line (area 0.767 vs 0.5, p = 0.001), the optimum cutoff point at 4.5 g and the sensitivity of 0.722 and specificity of 0.742 (Fig. 4). At 6 months post-partum, the ROC curve shows also a significant difference from the reference line (area 0.666 vs 0.5, p = 0.047), the optimum cutoff point at 5.5 g and the sensitivity of 0.629 and specificity of 0.619 (Fig. 4). Again, stratifying for stress incontinence or for severe symptoms of urinary incontinence, the ROC curve did not improve.

Discussion

In this study, we focussed on the use of pad testing to investigate its prognostic value for objectively measuring (the severity of) self-reported urinary incontinence during pregnancy and after childbirth. The clinical impact of incontinence in pregnancy and after childbirth is growing because some studies report the efficacy of physiotherapy in pregnancy and because obstetric choices are supposed to have a significant impact on post-reproductive urinary function [1]. This growing impact requires objective measurement. In a meta-analysis, the symptom of stress incontinence was 91% sensitive but only 51% specific for detecting genuine stress urinary incontinence as defined by the International Continence Society, based on history and urodynamic testing [18]. Because of pregnancy and because we are interested in an instrument for screening, it is obvious that urodynamic testing cannot be the instrument of choice. Pad testing is an objective, simple and non-invasive instrument capable of measuring fluid loss in a certain period. First of all, we need to define normal values, data that describe the results of pad testing in a cohort of pregnant women without a history of incontinence before pregnancy. Secondly, we need comparison with the criterion standard in pregnancy and the patients’ history.

The median weight gain in the 24-h pad test in pregnancy as reported in our study is in accordance with results reported in a group of non-pregnant, not incontinent, premenopausal women, 2.6–7.0 g, with an upper confidence limit of 5.5–8 g [16, 19]. In post-menopausal continent women, a much lower weight gain of 0.3 g is reported [20]. When compared to the pre-menopausal women, the state of pregnancy does not lead to a higher weight gain in the 24-h pad test nor does the puerperal state.

It is remarkable that the group of controls as referred to had similar pad test results but did not report incontinence, whereas in our pregnant group, 30 (28 weeks of pregnancy) and 35% (38 weeks of pregnancy) of the women did. With the same weight gain in pregnancy, women report more incontinence than in the sample of non-pregnant women. It seems therefore that not the amount of weight gain in the pad test but the pregnancy state itself is more discriminating for the chance that a woman qualifies herself as incontinent.

In our study, during pregnancy, pad test results had only limited diagnostic value for self-reporting of incontinence. In their review article, Ryhammer et al. [21] stated that “incontinence is a complex condition in which differences in the individual patients’ personal characteristics influence the perception of leakage and the identification of the problem. Pregnancy seems to modulate this perception in such a way that it cannot be measured by pad test. As pad testing did not show to have high sensitivity and specificity for self-reported urinary incontinence in pregnancy and after childbirth, there remains confusion about the accurate diagnosis. This becomes important in deciding on management options such as offering preventive physiotherapy in selected cases or strategies that influence the mode of delivery.

After childbirth, the median weight gain is also in accordance with results in non-pregnant continent women. In our study group, 15 to 18% of the women report positive for symptoms of incontinence. Just like in pregnancy, the pad test result has a significant value for testing self-reporting incontinence but again low figures for sensitivity and specificity. Like us, Morkved and Bo [22] reported a discrepancy between self-reported symptoms and stress urinary incontinence assessed by their (short) pad test, 8 weeks after delivery. To assign a women to an intervention, one needs a higher specificity, which according to the curves as shown, will rapidly lead to lower sensitivity. Depending on the chosen intervention, this may or may not be accepted.

The calculation of the diagnostic strength of our 24-h pad test was made with the self-reporting of symptoms of urinary incontinence as the gold standard. At 28 weeks, the pad test failed to capture eight subjects who stated they were wet; at 38 weeks, this was higher. Such results are possibly related to the high threshold for definition of incontinence in the women with some leaking less than 9 g describing some leakage. The rationale for using a high cutoff is established in both men and women, but subjects themselves may perceive this a severe incontinence. It is possible that pregnant and post-delivery women perceive leakage differently than their non-pregnant counterparts.

When adding severity of symptoms to the gold standard, as reported by VAS, the diagnostic strength of the pad test did not improve.

In general practice, questioning about incontinence will provide the clinician with adequate information on the presence, absence or severity of incontinence from a patient perspective, and cumbersome pad tests are unnecessary. In a review article on questionnaires for women with pelvic floor disorders, Barber [23] concludes that measuring symptom severity and quality of life changes in women with pelvic floor disorders is an important part of the evaluation and treatment of women and may be the only practical way to clinically assess symptoms. However, for the purposes of research, pad tests, combined with subjective/qualitative considerations, play a critical role in allowing comparisons across studies, quantifying the amount of urine loss and establishing a measure of severity. Indeed, the International Continence Society standards for research strongly recommend the pad test as one measure in all incontinence research. The fact that the pad test results and patient-reported incontinence were not strongly correlated illustrates the importance of both quantitative and qualitative measures when considered an intervention trial with pelvic floor muscle exercises, for example.

From our study, we conclude that pad testing measures fluid loss over a certain period but does not quantify self-reported symptoms of urinary incontinence. Both measurements are of interest but cannot replace each other. Stressing of the pelvic floor by pregnancy and childbirth modulates the sensation of urinary leakage in such a way that women in this state do report symptoms of urinary incontinence more frequently than nulliparous pre-menopausal women do.

References

Goldberg RP, Kwon C, Gandhi S, Atkuru LV, Sorensen M, Sand PK (2003) Urinary incontinence among mothers of multiples: the protective effect of cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 188:1447–1450

Francis WJ (1960) The onset of stress incontinence. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Emp 67:899–903

Burgio KL, Locher JL, Zyczynski H, Hardin JM, Singh K (1996) Urinary incontinence during pregnancy in a racially mixed sample: characteristics and predisposing factors. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 7:69–73

Stanton SL, Kerr-Wilson R, Harris VG (1980) The incidence of urological symptoms in normal pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 87:897–900

King JK, Freeman RM (1998) Is antenatal bladder neck mobility a risk factor for postpartum stress incontinence? Br J Obstet Gynaecol 105:1300–1307

Sampselle CM, Miller JM, Mims BL, DeLancey JO, Ashton-Miller JA, Antonakos CL (1998) Effect of pelvic muscle exercise on transient incontinence during pregnancy and after birth. Obstet Gynecol 91:406–412

Reilly ET (2002) Prevention of postpartum stress incontinence in primigravidae with increased bladder neck mobility: a randomised controlled trial of antenatal pelvic floor exercises. BJOG 109:68–76

Chiarelli P, Campbell E (1997) Incontinence during pregnancy. Prevalence and opportunities for continence promotion. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol 37:66–73

Wilson PD, Herbison RM, Herbison GP (1996) Obstetric practice and the prevalence of urinary incontinence three months after delivery. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 103:154–161

Versi E, Cardozo LD (1986) Perineal pad weighing versus videographic analysis in genuine stress incontinence. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 93:364–366

Ryhammer AM, Laurberg S, Djurhuus JC, Hermann AP (1998) No relationship between subjective assessment of urinary incontinence and pad test weight gain in a random population sample of menopausal women. J Urol 159:800–803

Matharu GGSAR (2004) Objective assessment of urinary incontinence in women: comparison of the one-hour and 24-hour pad tests. Eur Urol 45:208–212

Soroka D (2002) Perineal pad test in evaluating outcome of treatments for female incontinence: a systematic review. Int Urogynecol J 13:165–175

Groutz A (2000) Noninvasive outcome measures of urinary incontinence and lower urinary tract symptoms: a multicenter study of micturition diary and pad tests. J Urol 164:698–701

O’Sullivan R (2004) Definition of mild, moderate and severe incontinence on the 24-hour pad test. BJOG 111:859–862

Mouritsen LBGHJ (1989) Comparison of different methods for quantification of urinary leakage in incontinent women. Neurourol Urodyn 8:579–587

Abrams P (2003) The standardisation of terminology in lower urinary tract function: report from the standardisation sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Urology 61:37–49

Jensen JK, Nielsen FR Jr, Ostergard DR (1994) The role of patient history in the diagnosis of urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol 83:904–910

Lose G, Jorgensen L, Thunedborg P (1989) 24-hour home pad weighing test versus 1-hour ward test in the assessment of mild stress incontinence. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 68:211–215

Karantanis E (2003) The 24-hour pad test in continent women and men: normal values and cyclical alterations. BJOG 110:567–571

Ryhammer AM (1999) Pad testing in incontinent women: a review. Int Urogynecol J 10:111–115

Morkved S, Bo K (1999) Prevalence of urinary incontinence during pregnancy and postpartum. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 10:394–398

Barber MD (2007) Questionnaires for women with pelvic floor disorders. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 18:461–465

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Wijma, J., Weis Potters, A.E., Tinga, D.J. et al. The diagnostic strength of the 24-h pad test for self-reported symptoms of urinary incontinence in pregnancy and after childbirth. Int Urogynecol J 19, 525–530 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-007-0472-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-007-0472-z