Abstract

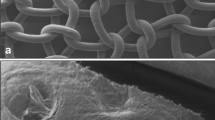

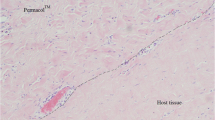

We compared inflammatory response, fibrosis and biomechanical properties of different polypropylene materials from one manufacturer (Tyco Healthcare) in a rat model for primary fascial repair. Full-thickness abdominal wall defects were primarily repaired using ‘overlay’ technique. Multifilament implants were Surgipro SPM and SPMW, the latter a wider-weave type of the former. Monofilament SPMM implants and polypropylene suture repair (Surgipro II) served as controls. Explants were evaluated macroscopically and changes in thickness, shrinkage and tensile strength were measured. Inflammatory and connective tissue response was assessed on haematoxylin-eosin and Movat stains. Immunohistochemistry was done to localise rat macrophages/monocytes. Multifilament materials induced a shorter acute inflammatory response and more pronounced chronic inflammatory reaction compared to monofilament implants. Macrophages could be found deep in interstices 7.5 by 12.5 μm. No difference in collagen deposition and neovascularisation was observed. At 90 days time point, explants reconstructed with tighter woven multifilament SPM were weaker than sutured or SPMM controls. Overall shrinkage of 10% was comparable for all groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

MacLennan AH, Taylor AW, Wilson DH et al (2000) The prevalence of pelvic floor disorders and their relationship to gender, age, parity and mode of delivery. BJOG 107:1460–1470

Birch C, Fynes MM (2002) The role of synthetic and biological prosthesis in reconstructive pelvic floor surgery. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 14:527–535

Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO et al (1997) Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol 89:501–506

Bellon JM, Contreras LA, Bujan J et al (1998) Tissue response to polypropylene meshes used in the repair of abdominal wall defects. Biomaterials 19:669–675

Ferrando JM, Vidal J, Armengol M et al (2001) Early imaging of integration response to polypropylene mesh in abdominal wall by environmental scanning electron microscopy: comparison of two placement techniques and correlation with tensiometric studies. World J Surg 25:840–847

Amid PK (1997) Classification of biomaterials and their related complications in abdominal wall hernia surgery. Hernia 1:15–21

Lamb JP, Vitale T, Kaminski DL (1983) Comparative evaluation of synthetic meshes used for abdominal wall replacement. Surgery 93:643–648

Lichtenstein IL, Shulman AG, Amid PK et al (1989) The tension-free hernioplasty. Am J Surg 157:188–193

Cervigni M, Natale F (2001) The use of synthetics in the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. Curr Opin Urol 11:429–435

Moriss-Stiff GJ, Hughes LE (1998) The outcomes of nonabsorbable mesh placed within the abdominal cavity: literature review and clinical experience. J Am Coll Surg 186:352–367

Beets GL, Go PM, van Marmeren H (1996) Foreign body reactions to monofilament and braided polypropylene mesh used as preperitoneal implants in pigs. Eur J Surg 162:823–825

Coates KW, Galan HL, Shull BL et al (1995) The squirrel monkey: an animal model of pelvic relaxation. Am J Obstet Gynecol 172:588–593

Yiou R, Delmas V, Carmeliet P et al (2001) The pathophysiology of pelvic floor disorders: evidence from a histomorphologic study of the perineum and a mouse model of rectal prolapse. J Anat 199:599–607

Mattson JA, Kuehl TJ, Yandell PM et al (2005) Evaluation of the aged female baboon as a model of pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic reconstructive surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 192:1395–1398

Alponat A, Lakshminarasappa SR, Yavuz N et al (1997) Prevention of adhesions by Seprafilm, an absorbable adhesion barrier: an incisional hernia model in rats. Am Surgeon 63:818–819

Zheng F, Lin Y, Verbeken E et al (2004) Host response after reconstruction of abdominal wall defects with porcine dermal collagen in a rat model. Am J Obstet Gynecol 191:1961–1970

Konstantinovic ML, Lagae P, Zheng F et al (2005) Comparison of host response to polypropylene and non-cross linked porcine small intestine serosal derived collagen implants in a rat model. BJOG 112:1554–1560

Stone IK, von Fraunhofer JA, Masterson BJ (1986) The biomechanical effects of tight suture closure upon fascia. Surg Gynecol Obstet 163:448–452

Baptista ML, Bonsack ME, Felemovicius I et al (2000) Abdominal adhesions to prosthetic mesh evaluated by laparoscopy and electron microscopy. J Am Coll Surg 190:271–280

Toosie K, Gallego K, Stabile BE et al (2000) Fibrin glue reduces intra-abdominal adhesions to synthetic mesh in a rat ventral hernia model. Am Surgeon 66:41–45

Law NW, Ellis H (1991) A comparison of polypropylene mesh and expanded polytetrafluoroethylene patch for the repair of contaminated abdominal wall defects: an experimental study. Surgery 109:652–655

Badylak S, Kokini K, Tullius B et al (2002) Morphologic study of small intestinal submucosa as a body wall repair device. J Surg Res 103:190–202

Damoiseaux JG, Dopp EA, Calame W et al (1994) Rat macrophage lysosomal membrane antigen recognized by monoclonal antibody ED1. Immunology 83:140–147

Debodinance P, Cosson M, Burlet G (1999) Tolerance of synthetic tissues in touch with vaginal scars: review to the point of 287 cases. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 87:23–30

Visco AG, Weidner AC, Barber MD et al (2001) Vaginal mesh erosion after abdominal sacral colpopexy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 184:297–302

Klinge U, Klosterhalfen B, Muller M et al (1998) Shrinking of polypropylene mesh in vivo: an experimental study in dogs. Eur J Surg 164:965–969

Le Blanc KA, Whitaker JM (2002) Management of chronic postoperative pain following incisional hernia repair with Composix mesh: a report of two cases. Hernia 6:194–197

Milani R, Salvatore S, Soligo M et al (2005) Functional and anatomical outcome of anterior and posterior vaginal prolapse repair with prolene mesh. BJOG 112:107–111

Coda A, Bendavid R, Botto-Micca F et al (2003) Structural alterations of prosthetic meshes in humans. Hernia 7:29–34

Amid PK (2003) The Lichtenstein repair in 2002: an overview of causes of recurrence after Lichtenstein tension-free hernioplasty. Hernia 7:13–16

Klinge U, Conze J, Klosterhalfen B et al (1996) Veranderung der bauchwandmechanik nach Mesh-implantation. Experimentelle veranderung der mesh-stabilitat. Langenbecks Arch Chir 381:323–332

Slack M, Sandhu JS, Staskin DR et al (2006) In vivo comparison of suburethral sling materials. Int Urogynecol J 17:106–110

Offner FA (2004) Pathophysiology and pathology of the foreign-body reaction to mesh implants. In: Schumpelick V, Nyhus LM (eds) Meshes: benefits and risks. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg New York, pp 161–167

Papadimitrou J, Petros P (2005) Histological studies of monofilament and multifilament polypropylene mesh implants demonstrate equivalent penetration of macrophages between fibrils. Hernia 9:75–78

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an unconditional grant from Tyco Healthcare (Mechelen, Belgium). The company donated standard commercially available implants. Tyco had no input into the surgical protocol, randomisation tables and no control on data analysis nor its reporting. The authors have no financial interests in this company; neither are they advisers to them. M. Konstantinovic is a recipient of a doctoral fellowship of Leuven Research and Development.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Konstantinovic, M.L., Pille, E., Malinowska, M. et al. Tensile strength and host response towards different polypropylene implant materials used for augmentation of fascial repair in a rat model. Int Urogynecol J 18, 619–626 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-006-0202-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-006-0202-y