Abstract

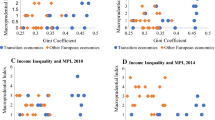

Rising income inequality coinciding with financial liberalization has stimulated extensive studies on the possible links between income inequality and different forms of financial liberalization, both inputs and outputs, since the 1990s. Nonetheless, empirical investigations remain inconclusive. To provide new and robust evidence, this study investigates the distributional repercussions of financial liberalization and the role played by democratization in this process. Focusing on the outcome measures of financial liberalization, we find, in a panel of developing and developed countries for 1989–2011, that (1) financial openness alleviates income inequality, particularly for less democratic countries; (2) stock market development mitigates income inequality, whereas its volatility exacerbates it, with both effects decreasing with democratization; (3) banking development strengthens income inequality, whereas its volatility alleviates it, with both effects again moderating with democratization; and (4) these effects are mediated by human capital accumulation and entrepreneurship development. The data thus suggest that financial reforms toward capital account openness and more liquid, stable stock markets are beneficial to income distribution, as such reforms allow more previously excluded households and firms to access financial funds and services, thereby increasing human capital and entrepreneurship, especially in less democratic countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For instance, Das and Mohapatra (2003), Beck et al. (2010), Agnello et al. (2012), Delis et al. (2014), Bumann and Lensink (2016), Christopoulos and McAdam (2017), Haan and Sturm (2017), Furceri and Loungani (2018), and Manish and O’Reilly (2018) consider the input/policy measure of financial liberalization such as bank regulation and capital market liberalization policy. Others including Jalilian and Kirkpatrick (2005), Clarke et al. (2006), Beck et al. (2007), Kim and Lin (2011), Law et al. (2014), Jauch and Watzka (2016), D’Onofrio et al. (2017), Haan and Sturm (2017), and Blau (2018) focus on outcome measures such as capital (e.g., foreign direct investment, FDI) flows and the size and stability of the financial sector.

For instance, Law et al. (2014), Cepparulo et al. (2017), and De Hann and Strum (2017) also explore the role of political institutions. Cepparulo et al. (2017), in a sample of developing countries from 1984 to 2012, find that the pro-poor impact of banking development decreases as the quality of institutions rises. Law et al. (2014), using a sample of 81 countries averaged over 1985–2010, show that banking development tends to reduce income inequality only after a certain threshold level of institutional quality has been achieved. Using a panel fixed effects model for a sample of 121 countries covering 1975–2005, De Hann and Strum (2017) demonstrate that banking development raises income inequality irrespective of the quality of political institutions. We differ from these studies by considering not only banking development but also stock market development. We also consider actual financial openness and financial volatility as well as the mechanisms of how these financial variables affect income inequality.

We also check whether the diminishing effects of financial liberalization on inequality with increasing democratization are simply because of too much finance, as suggested by Arcand et al. (2015). Including the squares of the financial liberalization indicators, we continue to find that the financial variables and their interaction with democratization retain their signs and significance. This means that democratization captures more than the financial curse of Arcand et al. (2015). Further, we replace GDP growth with log real GDP per capita and its quadratic term; the financial variables and their interaction with democratization retain their signs and significance. These results are not reported to save space but are available on request.

The only exception is for the Column (3) regression perhaps because of using too many endogenous variables. We find a similar case for the following two tables.

Liu et al. (2017) also find that a rise in turnover in the stock market augments income inequality in China.

This might also explain the larger number of instruments than countries.

The quantile regression approach, introduced by Koenker and Bassett (1978), has gained increasing popularity in applied economics and has recently been extended to panel data with additive fixed effects and combined instrumental variable techniques in a quantile setting (e.g., Koenker 2004; Galvao 2011; Harding and Lamarche 2014). However, all these estimators are consistent in large-T samples. More recently, Powell (2016) and Powell and Wagner (2014) exploit the ideas of Chernozhukov and Hansen (2008) and propose a different estimator, based on instrumental variables. The estimator is consistent for small T. This is the most suitable method for our study given the small T and endogeneity of the regressors. Please see Powell (2016) for more details.

References

Acemoglu D, Johnson S (2005) Unbundling institutions. J Polit Econ 113:949–995

Acemoglu D, Robinson JA (2000) Democratization or repression? Eur Econ Rev 44:683–693

Acemoglu D, Robinson JA (2005) Economic origins of dictatorship and democracy. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Acemoglu D, Robinson J (2006) Economic origins of dictatorship and democracy. Cambridge University Press, New York

Acemoglu D, Naidu S, Restrepo P, Robinson JA (2015) Democracy, redistribution, and inequality. In: Atkinson AB, Bourguignon F (eds) Handbook of income distribution, vol 2. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 1885–1966

Aghion P, Bolton P (1992) An incomplete contracts approach to financial contracting. Rev Econ Stud 59:473–494

Agnello L, Sousa RM (2012) How do banking crises impact on income inequality? Appl Econ Lett 19:1425–1429

Agnello L, Mallick SK, Sousa RM (2012) Financial reforms and income inequality. Econ Lett 116:583–587

Aizenman J, Pinto B (eds) (2005) Managing economic volatility and crises: a practitioner’s guide. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Alessandria G, Qian J (2005) Endogenous financial intermediation and real effects of capital account liberalization. J Int Econ 67:97–128

Ansell BW, Samuels DJ (2014) Inequality and democratization: an elite-competition approach. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Arcand JL, Berkes E, Panizza U (2015) Too much finance? J Econ Growth 20:105–148

Arellano M, Bond S (1991) Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Rev Econ Stud 58:277–297

Arellano M, Bover O (1995) Another look at the instrumental variable estimation of error-components models. J Econom 68:29–51

Banerjee AV, Newman AF (1993) Occupational choice and the process of development. J Polit Econ 101:274–298

Barro RJ, Lee JW (2013) A new data set of educational attainment in the world, 1950-2010. J Dev Econ 104:184–198

Beck T, Demirgüç-Kunt A, Levine R (2007) Finance, inequality and the poor. J Econ Growth 12:27–49

Beck T, Levine R, Levkov A (2010) Big bad banks? The winners and losers from bank deregulation in the United States. J Finance 65:1637–1667

Bencivenga VR, Smith BD, Starr RM (1995) Transaction costs, technological choice, and endogenous growth. J Econ Theory 67:53–117

Blau BM (2018) Income inequality, poverty, and the liquidity of stock markets. J Dev Econ 130:113–126

Blundell R, Bond S (1998) Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. J Econom 87:115–143

Boix C (2003) Democracy and redistribution. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Bollerslev T (1986) Generalized autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity. J Econ 31:307–327

Bonica A, McCarty N, Poole KT, Rosenthal H (2013) Why hasn’t democracy slowed rising inequality? J Econ Perspect 27:103–124

Boyd JH, Smith BD (1998) The evolution of debt and equity markets in economic development. Econ Theory 12:519–560

Breen R, García-Peñalosa C (2005) Income inequality and macroeconomic volatility: an empirical investigation. Rev Dev Econ 9:380–398

Bumann S, Lensink R (2016) Capital account liberalization and income inequality. J Int Money Finance 61:143–162

Byrne JP, Davis EP (2005a) Investment and uncertainty in the G7. Rev World Econ 141:1–32

Byrne JP, Davis EP (2005b) The impact of short- and long-run exchange rate uncertainty on investment: a panel study of industrial countries. Oxford Bull Econ Stat 67:307–329

Cepparulo A, Cuestas JC, Intartaglia M (2017) Financial development, institutions, and poverty alleviation: an empirical analysis. Appl Econ 49:3611–3622

Chernozhukov V, Hansen C (2008) Instrumental variable quantile regression: a robust inference approach. J Econom 142:379–398

Christopoulos D, McAdam P (2017) Do financial reforms help stabilize inequality? J Int Money Finance 70:45–61

Claessens S, Perotti E (2007) Finance and inequality: channels and evidence. J Comp Econ 35:748–773

Clarke GRG, Xu LC, Zou H-F (2006) Finance and income inequality: What do the data tell us? South Econ J 72:578–596

Crotty J (2003) The neoliberal paradox: the impact of destructive product market competition and impatient finance on nonfinancial corporations in the neoliberal era. Rev Rad Polit Econ 35:271–279

D’Onofrio A, Minetti R, Murro P (2017) Banking development, socioeconomic structure and income inequality. J Econ Behav Organ forthcoming

Das M, Mohapatra S (2003) Income inequality: the aftermath of stock market liberalization in emerging markets. J Empir Finance 10:217–248

De Haan J, Sturm J-E (2017) Finance and income inequality: a review and new evidence. Eur J Polit Econ 50:171–195

Delis MD, Hasan I, Kazakis P (2014) Bank regulations and income inequality: empirical evidence. Rev Finance 18:1811–1846

Demirgüç-Kunt A, Levine R (2009) Finance and inequality: theory and evidence. Ann Rev Financ Econ 1:287–318

Demirgüç-Kunt A, Feyen E, Levine R (2013) The evolving importance of banks and securities markets. World Bank Econ Rev 27:476–490

Furceri D, Loungani P (2018) The distributional effects of capital account liberalization. J Dev Econ 130:127–144

Galor O, Zeira J (1993) Income distribution and macroeconomics. Rev Econ Stud 60:35–52

Galvao AF Jr (2011) Quantile regression for dynamic panel data with fixed effects. J Econom 164:142–157

Gimet C, Lagoarde-Segot T (2011) A closer look at financial development and income distribution. J Bank Finance 35:1698–1713

Greenwood J, Jovanovic B (1990) Financial development, growth, and the distribution of income. J Polit Econ 98:1076–1107

Haber S, North DC, Weingast BR (eds) (2007) Political institutions and financial development. Stanford University Press, Stanford

Harding M, Lamarche C (2014) Estimating and testing a quantile regression model with interactive effects. J Econom 178:101–113

Hsieh J, Chen TC, Lin SC (2019) Financial structure, bank competition and income inequality. North Am J Econ Finance 48:450–466

Huang Y (2010) Political institutions and financial development: an empirical study. World Dev 38:1667–1677

Jalilian H, Kirkpatrick C (2005) Does financial development contribute to poverty reduction? J Dev Stud 41:636–656

Jauch S, Watzka S (2016) Financial development and income inequality: a panel data approach. Empir Econ 51:291–314

Jensen NM (2003) Democratic governance and multinational corporations: political regimes and inflows of foreign direct investment. Int Organ 57:587–616

Kim D-H, Lin S-C (2011) Nonlinearity in the financial development-income inequality nexus. J Comp Econ 39:310–325

Koenker R (2004) Quantile regression for longitudinal data. J Multivar Anal 91:74–89

Koenker R, Bassett G (1978) Regression quantiles. Econometrica 46:33–50

Kohler K, Guschanski A, Stockhammer E (2016) How does financialization affect functional income distribution? A theoretical clarification and empirical assessment. Soc-Econ Rev 20:1–26

La Porta R, Lopez-de-Silanes F, Shleifer A, Vishny RW (1998) Law and finance. J Polit Econ 106:1113–1155

Lane PR, Milesi-Ferretti GM (2007) The external wealth of nations mark II: revised and extended estimates of foreign assets and liabilities, 1970–2004. J Int Econ 73:223–250

Laursen T, Mahajan S (2005) Volatility, income distribution, and poverty. In: Aizenman J, Pinto B (eds) Managing economic volatility and crises: a practitioner’s guide. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Law SH, Tan HB, Azman-Saini WNW (2014) Financial development and income inequality at different levels of institutional quality. Emerg Markets Finance Trade 50:21–33

Levine R (1991) Stock markets, growth and tax policy. J Finance 46:1445–1465

Levine R (2005) Finance and growth: theory and evidence. In: Aghion P, Durlauf S (eds) Handbook of economic growth. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Li Q (2006) Political violence and foreign direct investment. In: Fratianni M, Rugman AM (eds) Research in global strategic management, vol 12. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 231–255

Li Q, Resnick A (2003) Reversal of fortunes: democratic institutions and FDI inflows to developing countries. Int Organ 57:175–211

Lin K-H, Tomaskovic-Devey D (2013) Financialization and U.S. income inequality, 1970–2008. Am J Sociol 118:1284–1329

Liu G, Liu Y, Zhang C (2017) Financial development, financial structure and income inequality in China. World Econ 40:1890–1917

Mahler VA (2004) Economic globalization, domestic politics, and income inequality in the developed countries: a cross-national study. Comp Polit Stud 37:1025–1053

Manish GP, O’Reilly C (2018) Banking regulation, regulatory capture and inequality. Public Choice. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-018-0501-0

Marshall MG, Gurr TR, Jaggers K (2017) Polity IV Project: political regime characteristics and transitions, 1800–2016. Center for Systemic Peace

Mehlum H, MoeneKO TR (2012) Mineral rents and social development in Norway. In: Hujo K (ed) Mineral rents and the financing of social policy. Palgrave Macmillan, London

Mishkin FS (2007) Is financial globalization beneficial? J Money Credit Bank 39:259–294

Mishkin FS (2009) Globalization and financial development. J Dev Econ 89:164–169

Modigliani F, Perotti E (2000) Security markets versus bank finance. Legal enforcement and investor protection. Int Rev Finance 1:81–96

Perotti EC, Volpin P (2007) Politics, investor protection and competition. University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam

Powell D (2016) Quantile regression with nonadditive fixed effects. Available at: http://works.bepress.com/david_powell/1/

Powell D, Wagner J (2014) The exporter productivity premium along the productivity distribution: evidence from quantile regression with nonadditive firm fixed effects. Rev World Econ 150:763–785

Rajan RG (1992) Insiders and outsiders: the choice between informed and arm’s length debt. J Finance 47:1367–1400

Rajan RG, Ramcharan R (2011) Land and credit: a study of the political economy of banking in the United States in the early 20th century. J Finance 66:1895–1931

Rajan RG, Zingales L (1998) Which capitalism? Lessons from the East Asian crisis. J Appl Corpor Finance 11:40–48

Rajan RG, Zingales L (2003) The great reversals: the politics of financial development in the twentieth century. J Financ Econ 69:5–50

Ramey G, Ramey VA (1995) Cross-country evidence on the link between volatility and growth. Am Econ Rev 85:1138–1151

Rodrik D (1998) Why do more open economies have bigger governments? J Polit Econ 106:997–1032

Roine J, Vlachos J, Waldenström D (2009) The long-run determinants of inequality: what can we learn from top income data? J Public Econ 93:974–988

Roodman D (2009) A note on the theme of too many instruments. Oxford Bull Econ Stat 71:135–158

Solt F (2009) Standardizing the world income inequality database. Soc Sci Q 90:231–242

Stiglitz JE (2000) Capital market liberalization, economic growth, and instability. World Dev 28:1075–1086

van Treeck T (2009) The political economy debate on ‘Financialization’—A macroeconomic perspective. Rev Int Polit Econ 16:907–944

Windmeijer F (2005) A finite sample correction for the variance of linear efficient two-step GMM estimators. J Econom 126:25–51

Yang B (2011) Does democracy foster financial development? An empirical analysis. Econ Lett 112:262–265

Zalewski DA, Whalen CJ (2010) Financialization and income inequality: a post Keynesian institutionalist analysis. J Econ Issues 44:757–777

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the anonymous referee for valuable suggestions and comments that improve the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Shu-Chin Lin: The usual disclaimer applies.

Appendices

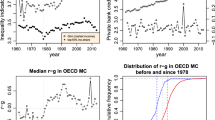

Appendix 1: measuring volatility

1.1 Measuring volatility

We follow Byrne and Davis (2005a, b) by proxying for financial volatility using conditional standard deviations obtained from the GARCH (1, 1) model. A standard GARCH model consists of mean and variance equations. For each country \( i \), we fit an ARMA (\( p, q \)) (autoregressive moving average) model to the mean equation of financial development \( \left( {finvol_{t} } \right): \)

where \( \varepsilon_{t} \) is the white noise at time \( t \). We choose a model for \( p \) and \( q \) using the Schwarz Bayesian criterion. For conditional heteroskedasticity, we assume that.

where \( \varOmega_{t - 1} \) denotes the information set to time \( t - 1 \), \( h_{t} \) represents conditional variance at time \( t \), and \( \eta_{t} \sim NID\left( {0,1} \right). \) We then use the GARCH(1,1) specification proposed by Bollerslev (1986) as follows:

Appendix 2: descriptive statistics and list of Countries

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, DH., Hsieh, J. & Lin, SC. Financial liberalization, political institutions, and income inequality. Empir Econ 60, 1245–1281 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-019-01808-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-019-01808-z