Abstract

Due to its excellent specific mechanical properties, carbon fibre-reinforced polymer (CFRP) composite is a widely used structural material in the aerospace industry. However, this material is difficult to cut, mainly due to its inhomogeneity and anisotropic features and because of the strong wear effects of its carbon fibres. In the scope of aerospace industrial uses of this material, thousands of holes have to be machined for purposes of assembly. Nevertheless, conventional drilling technology – even if special drilling tools are used – is only moderately able to manufacture good quality holes. Wobble milling is a novel advanced hole-making technology, which has been developed to minimize machining-induced geometrical defects like delamination or uncut fibres. The main objective of the present paper is to compare wobble milling, helical milling and conventional drilling technologies concerning unidirectional CFRPs. In addition, the kinematics of wobble milling technology is discussed in detail. In the scope of this paper, numerous machining experiments were conducted in unidirectional CFRPs: herein the impact of the type of cutting tool and of process parameters on the quality of machined holes are analysed and discussed (diameter of holes, circularity error and characteristics of uncut fibres). During these investigations, experimental data were evaluated with the help of digital image processing (DIP) and with the help of analysis of variance (ANOVA) techniques. Experimental results show that the amount of uncut fibres can significantly be minimized through the application of wobble milling technology.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Specific mechanical properties of carbon fibre-reinforced polymer (CFRP) laminates are excellent [1, 2]: these composite materials are therefore widely used in high-tech industries like the automobile and aerospace industries [3]. CFRP laminates can be ready-to-shape manufactured using numerous advanced and automated technologies like autoclave or closed mould vacuum bagging [4, 5]. Nevertheless, after the curing processes, there are still many micro- and macro-geometrical features that have to be machined mechanically. In the aerospace industry, thousands of high-quality holes have to be machined in order to assemble CFRP parts [6, 7]. However, CFRP composites are difficult-to-cut materials due to their (i) anisotropic and (ii) inhomogeneous features, and because of (iii) the abrasive wear effects of their carbon fibres on the cutting tool [8,9,10,11,12]. Furthermore, in this case, carbon-chip treatment is also problematic [13] as the chips have to be removed from the machining zone due to (i) health issues and (ii) the wear effect of the carbon fibres on the different parts of the machine tool.

In case improper machining technology is applied when machining CFRPs, many micro- and macro-geometrical damages can be generated easily: such damages include delamination [6, 7, 14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24], uncut fibres and pull-outs [13, 25,26,27,28,29,30,31] as well as microcracks on the machined surfaces [30, 32,33,34]. In order to minimize the above-listed damages, there are many process and technological parameters that have to be optimized including (i) the geometry and coating of the cutting tool [18, 33]; (ii) the cutting speed, feed rate and the depth of cut [7, 18, 35]; (iii) the tool path [7, 13, 32]; (iv) the cooling [36,37,38,39]; and (v) the type of support plate [40,41,42].

Even if previously many researchers investigated the impacts of technological and process parameters on conventional drilling induced damages in CFRPs, the number of scientific studies as far as the helical [7, 32, 35, 43,44,45,46,47], tilted helical [48, 49] and wobble milling [50,51,52] of CFRPs are concerned is limited.

2 Conventional drilling and helical milling of CFRPs

Conventional drilling technology does not require any difficult tool paths or machine tools; this technology can therefore be easily adapted by the industry. Nevertheless, due to the push-out effect of the drilling tool during exiting the composite, laminated layers can easily separate from each other: delamination and uncut fibres can be formed [23]. Davim et al. [53] outlined that feed rate has the highest physical and statistical impact on delamination during conventional drilling of CFRPs. Furthermore, improper geometry of the cutting tool can peel up the top layers of the composite and can also form geometrical defects [7]. Gaitonde et al. [6] claim that high-speed cutting can play a major role in reducing the damage at the entrance of the hole and that the combination of low feed rate and point angle is also important in minimizing delamination during the drilling of CFRP composites. Rubio et al. [54] also concluded that high-speed cutting in drilling is suitable for reducing damage and that it could also increase material removal rate. Given this, researchers and tool manufacturers have developed special cutting tool geometries in order to decrease peel-up and push-out effects [55]. Vigneshwaran et al. [56] observed that for achieving better drilling results, it is recommended to develop novel drilling tools. Abrão et al. [57] showed that 56% of the tools used for drilling polymer composites have a special geometry. Some of the special drilling tools developed for CFRP cutting are as follows: (i) double point angle twist drills [58,59,60,61,62,63,64], (ii) brad and spur drills [21, 65,66,67,68,69,70], (iii) dagger drills (one-shot drills) [28, 31, 67,68,69,70,71,72,73], (iv) step drills [67, 68, 74,75,76,77,78,79,80], (v) core drills [81, 82] and (vi) special core drills [83,84,85]. These special drilling tools are reviewed and discussed in detail by Geier et al. [55].

It is often possible to produce good quality holes with the help of special drilling tools (often featuring diamond coating) using optimized process parameters. However, these technologies often require a considerable amount of optimisation time and cost. Therefore, researchers developed novel milling technologies in order to decrease tool costs and to improve hole quality. Special hole machining technologies, like helical milling, tilted helical milling or wobble milling, require longer operation times due to longer tool paths, but the amount of machining necessitated by geometrical defects as well as tool cost can significantly be decreased when such special hole machining technologies are applied.

Tool paths of helical milling (also known as orbital drilling) are more complex than tool paths of conventional drilling: operation time of helical milling is therefore longer and more time is needed for optimisation [86]. As can be seen on Fig. 1a, the axial force component of cutting force can still peel up the upper laminated layers of the composite, but the push-out effect is minimal due to the compression axial cutting force (Fa) component. Machining-induced geometrical defects can therefore be decreased at the exit of the holes, according to Wang et al. [44]. Furthermore, helical milling technology usually does not require special milling tools; thus it can be more effective than conventional drilling, as demonstrated by Geier and Szalay [7].

Conventional drilling and helical milling strategies in CFRPs were compared by Voss et al. [86]. They found that orbital drilling produces fewer geometrical defects (delamination and uncut fibres) in CFRPs than conventional drilling, which Geier and Szalay [7] also observed. However, the operation time of orbital drilling was two to four times longer than that of conventional drilling. Furthermore, Brinksmeier et al. [87] described the kinematics of helical milling. They showed that axial cutting force can be decreased significantly if helical milling technology is used. Qin et al. [43] analysed delamination with the help of artificial neural networks during the helical milling of CFRPs. Qin et al. found that helical milling has great potentials in comparison with conventional drilling. Based on a multi-objective Pareto genetic algorithm, Wang et al. [44] optimized cutting parameters (cutting speed, tangential and axial feed rates) during helical milling in order to optimize cutting force, peel-up delamination and productivity. Chang et al. [88] studied micro helical milling using flat end mills. They concluded that the micro-cutting efficiency of micro helical milling is theoretically larger than that of conventional micro-cutting.

Li and Liu [32] analysed surface topography and surface roughness of hole making with respect to helical milling. They stated that material removal rate can be maximized, while the surface roughness of machined surfaces can easily be controlled. Liu et al. [45] analysed the temperature variation of helical milling with respect to CFRPs. Their proposed temperature prediction model is able to simulate the temperature distribution of CFRP workpieces. Additionally, Sakamoto and Iwasa [35] examined cutting temperature during helical milling using a ball nose end mill. They showed that compressed air could efficiently reduce heat at the cutting point. Using ultrasonic vibration and liquid nitrogen, Ishida et al. [46] analysed the thrust force, tool wear and accuracy of machined holes in the case of helical milling. They concluded that thrust force could be reduced when using ultrasonic-vibration-assisted helical milling and cryogenic cooling. In addition, Haiyan and Xuda [89] developed a mechanistic force model in order to predict cutting force in the case of helical milling of CFRPs.

2.1 Wobble milling of CFRPs

Wobble milling is an advanced hole machining technology. During wobble milling, axial cutting force at the hole entry can be further decreased by tilting the cutting tool, as can be seen on Fig. 1b. By tilting the cutting tool, the acting cutting force compresses the upper and downer laminated layers of the composite; therefore peel-up and push-out effects can be minimized. Tool movements can only be implemented by a complex machine tool or an industrial robot: this technology is therefore more expensive and needs detailed design and optimisation. However, there are some industrial fields (like aerospace and space industries) where huge CFRP parts are manufactured by industrial robots. In these contexts, the implementation of wobble milling yields no additional machine tool costs.

Schulze et al. [50] observed that machining-induced damage can be reduced by advanced, complex machining strategies, which direct cutting forces inwards. Schulze and Beke [52] investigated the impacts of process and workpiece parameters – such as feed, tool inclination, tool spiral angle and cutting-edge radius – on resultant machining force vectors. They also showed that wobble milling is insensitive to tool wear and they developed a mechanistic model to calculate chip geometry and specific forces in the scope of their study [51]. In addition, they figured out that during wobble milling the top laminated layers of CFRPs can be machined with the resulting process force vector directed towards the centre of the workpiece. Furthermore, they stated that five-axial advanced machining strategies can achieve better quality holes than conventional drilling. It can thus be concluded that the number of studies on wobble milling is fairly limited: a more extensive discussion of the kinematics and usability of wobble milling of CFRPs is therefore required.

The main objective of the present paper is to compare wobble milling, helical milling and conventional drilling technologies in the case of unidirectional CFRPs. Furthermore, the kinematics of wobble milling technology is also discussed in detail. In the scope of our investigations, numerous machining experiments were conducted in the case of UD-CFRPs using three different milling tools. In the present study, the impacts of (i) the type of cutting tool, (ii) of feed rate and (iii) of the depth of cut (i) on the machined diameter of holes, (ii) on the circularity error and (iii) on the characteristics of uncut fibres are analysed and discussed.

2.2 Setup and methods of the experiment

In the scope of this study, holes were machined in UD-CFRPs using three different drilling strategies: (i) conventional drilling, (ii) helical milling and (iii) wobble milling. The kinematics of conventional drilling and helical milling is moderately complex, but the kinematics of wobble milling merit a more thorough discussion.

2.3 The kinematics of wobble milling

Wobble milling is an advanced hole-making technology, which can effectively decrease geometrical damage (e.g. delamination, uncut fibres, fibre pull-outs) on machined surfaces. However, this technology requires a complex five-axis motion cycle. This advanced tool path can be generated by special machines, by industrial robots or by five-axis machining centres. In the case of huge CFRP parts to be machined, the parts are usually fixed and the cutting tool makes the following movements.

First, the tool centre point (TCP) assumes the starting position of the cycle (situated above the centre of the hole), as can be seen in Fig. 2a. Then the tool moves on a linear path at a feed rate (vf) until reaching the drilling depth, as can be seen in Fig. 2b. Second, the cutting tool starts to rotate around the centre point of the hole (O – intersection point of the axis of the tool and the axis of the hole – which is the rotation point), until the axis of the tool reaches the required tilting angle (βv). Simultaneously with performing the tilting movement, the tool starts to rotate around the hole axis (ω), as illustrated in Fig. 2c and d. After the axis of the cutting tool has reached the nominal diameter of the final tilting value (βv), the cutting tool returns to the vertical position and stops rotating around the hole axis, as can be seen in Fig. 2e. Afterwards, the cutting tool starts to rotate around the hole axis (ω) and moves away from it (r) at a feed rate (vf), as illustrated in Fig. 2f. Finally, the tool retracts from the surface of the hole and returns to the starting point of the wobble milling cycle, as illustrated in Fig. 2g and h.

Schematic diagram of the kinematics of wobble milling: (a) positioning, (b) conventional drilling (pilot hole drilling), (c) starting the tilting movements, (d) reaching the nominal diameter, (e) returning to the vertical position, (f) helical milling, (g) retracting and (h) returning to the start position of the wobble milling cycle

The geometrical model of the wobble milling used in this study can be seen in Fig. 4. Based on this model, the discrete points of the tool path of the milling cycle can be generated, using trigonometrical correlations and interdependencies, as follows:

- (i)

One of the main objectives was to describe and program the wobble milling cycle in as simple terms as possible. It was also a significant aim to develop a flexible and accurate algorithm to ensure the widespread use of this application. Last but not least, it was a further goal to automate CNC code generation.

- (ii)

In the case of the application of conventional tool offsets (programming the tip point of the tool), five axis movements have to be defined and programmed. However, by way of the offsetting of the programmed points (TCP – tool centre point) to the centre point of the hole (O), only two coordinates have to be defined and programmed. This approach is applied in the scope of this study, too.

- (iii)

Due to the kinematics of the machine tool used in the scope of this study, rather than rotating the cutting tool, it was the workpiece that was rotated on a rotary table (ω), as shown in Fig. 2. Based on relevant simplifications, just two coordinates were calculated: the rotation of the Table (C) and the rotation of the spindle (B).

- (iv)

Finishing the final surface of the hole was accomplished with the help of a spiral tool path, using a fixed value of cutting width (a). The spiral tool path was ensured by way of the rotation of the workpiece and the linear movement of the tool.

An algorithm was developed in order to calculate i (number of rotations of axis C), βi(position of axis B during a full rotation of axis C) and βv (final position of axis B). The algorithm can be seen in Fig. 3.

The parameters of Fig. 3 are shown and explained in Fig. 4, where d is the nominal tool diameter, D is the required nominal hole diameter, h is the thickness of the workpiece, a is the cutting depth, β is the tool rotation, while F and P are assistant parameters facilitating the easier calculation of the number of rotations, as expressed by Eqs. (1) and (2), respectively.

Geometric model for calculating tilting movements of the cutting tool when using wobble milling technology; a shows the cutting width (depth of cut), h is the thickness of the machined plate, O is the programmed point of the cutting tool (identical to the rotational point of the tool) and β is the tilting angle

The equations were calculated to ensure a constant cutting depth (a) during the process, as shown in Fig. 4. As a first step, the last and the first tool rotations were calculated; then, if it was necessary, further tool rotations were also calculated. When the currently calculated tool rotation reached a higher value than that of the last tool rotation, the algorithm stopped, and the tool value rotations (βi) in each full workpiece rotation were saved for further processing.

The CNC program for wobble milling was generated based on the algorithm shown in Fig. 5. This algorithm was experimentally tested and validated. In the above figure, q is the resolution of the rotary table expressed in degrees, n is the spindle speed, F are the feed rates, f is the parameter that counts the number of rotations of the rotary table and e is the parameter that counts generated calculated controlled positions. This algorithm generates (i) the pilot hole drilling path and then (ii) the controlled points for wobble milling and then creates (iii) the helical milling path for the final machining step. (These steps were discussed in detail in relation to Fig. 2.) The algorithm is independent of any type of CNC controller; it can therefore be applied in any CNC environments with the following main limitations: (i) the axis of the hole has to be parallel to the axis of the rotary table; furthermore, (ii) the tool offset has to be specifically set, as discussed before.

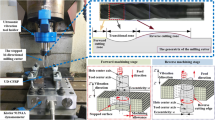

2.4 Experimental setup

A unidirectional carbon fibre-reinforced polymer (UD-CFRP) composite material was applied for the machining experiments, where the matrix material was vinyl ester. The composite plate thickness was h = 5 mm. The CFRP specimens were prepared by a water jet machine: specimens with a diameter of d = 34 mm were cut.

The experiments were conducted on two different machine centres. A VHTC 130 linear machining centre (five axis) was used for the wobble milling experiments, with a maximum speed of ω = 3000 °/min concerning the machine’s rotary table. This feature limited the maximal feed rate to vf = 262 mm/min (calculated for a diameter of 10 mm). A Kondia 640B machining centre (three axis) was used for the conventional drilling and helical milling experiments. Both of the cutting machine centres were equipped with a Nilfisk GB7333 vacuum cleaner in order to clear the cutting area of the carbon chips.

Two different types of compression end mills and a conventional end mill were applied in the scope of the experiments. The cutting tools can be seen on Fig. 6, and their important parameters are summarized in Table 1. Each of the cutting tools is made of uncoated solid carbide. The compression end mills differ from each other in the number and size of the cutting edges: the medium tool has more but smaller cutting edges than the coarse tool, as can be seen in Fig. 6a and b. Tools with a working diameter of d = 6 mm were applied for the helical and wobble milling experiments, and d = 10 mm tools were used in the scope of conventional drilling experiments.

A special fixture was designed and manufactured for the wobble milling experiments, as can be seen in Fig. 7. It was designed to fit in a h = 4–6 mm thick CFRP workpiece, with a diameter of dw = 30–35 mm. The α = 90° cone ensures that the tool can take up a position at the required angle (~ 31°). The fixture has an n = 3 socket head screw, with spring washers ensuring an appropriate clamping force. With the help of this fixture, the clamp was equipped with an evenly balanced support at a location close to the final diameter. This arrangement also minimized the vibration of the workpiece. The back-up support of the CFRP specimen was fixed to ds = 15 mm (p = 150% of the nominal hole diameter). A special back-up support plate (Fig. 8) was also used for the conventional and helical milling experiments in order to minimize peel-up and push-down delamination effects.

A Zeiss UMC 850 coordinate measuring machine (CMM) was used to measure the diameter and circularity errors of the holes. N = 500 measuring points were used for each hole at a depth of the centre plane of the plates (at a depth of z = 2.5 mm). The cutting wavelength was set to 50 UPR Gaussian filter, based on the hole diameter. The speed of touch probe was set to v = 2 mm/s and the touch probe radius was r = 1 mm. Furthermore, a Dino-Lite Pro 123–012676 digital microscope was used to record images of the entry and exit sides of the holes. In order to ensure the same conditions, photos were taken in the lower half of the fixture, and for this purpose, the same settings were used.

Due to the extremely high experimental costs (cutting tool, specimens, etc.), the number of experiments of wobble milling had to be minimized. The experiments were therefore designed based on a central composite face centred (CCF) design, using Minitab software. The factors were chosen in line with previous studies: thus feed rate (vf) and cutting width (a) were set based on previous studies. Minimum and maximum levels of the factor space of the experiments were set to vf,min = 150 mm/min, vf,max = 250 mm/min, amin = 0.05 mm and amax = 0.95 mm, based on previous studies [20, 50, 52] and in line with suggestions by tool producers. Cutting speed was fixed to 160 m/min. Table 2 shows an experimental matrix table for wobble milling. The centre point was repeated n = 5 times to satisfy the necessary conditions of statistical calculations. This method was implemented and repeated for each tool type (A, B and C).

The cutting speed of conventional drilling and helical milling was fixed to 160 m/min. The feed rates of (i) conventional drilling, (ii) of the pilot hole drilling before executing helical milling and (iii) of the pilot hole drilling during wobble milling were vf = 700 mm/min. The feed rates concerning the finishing movements of the hole surface are listed in Table 3. Each experimental setup was repeated three times due to reasons of statistical analysis.

2.5 Digital image processing

In computer science, digital image processing (DIP) consists in the use of computer algorithms for performing image processing on digital images [90]. Many researchers [23, 25, 26, 28, 29, 47] characterized the quality of machined holes in CFRPs by using parameters calculated using different DIP methods. Yet, some of these parameters were not specific (diameter-independent) values. In this research, a diameter-specific parameter was used to characterize the quality of drilled holes. In the scope of the experiment, digital images were taken by a Dino-Lite microscope and then were prepared for analysis using the following method:

- (i)

The master lightness bar was decreased by 39 points, and the saturation was increased by 70 points in order to increase the contrast, as can be seen in Fig. 9b .

- (ii)

Red, cyan, blue and purple bars were decreased by 200%; yellow and green bars were increased by 300% in order to segment the image (transform colours to grey pixels), as can be seen in Fig. 9c.

- (iii)

Brightness was increased by 50 points, and contrast was increased by 100 points in order to filter unnecessary pixels (see Fig. 9d.

- (iv)

Contrast was increased by 100 points to increase more accurate edge detection (Fig. 9e).

- (v)

The image was further filtered by medium noise reduction using 2-pixel radius adjustments. As a final result, the images were nearly assessable (Fig. 9f).

- (vi)

Ultimately, each image was checked and the pixel errors were fixed manually.

The above-described algorithm was programmed in Adobe Photoshop CS6 Extended graphical software in order to analyse the flexible, precise and high-level reproducibility of images.

Further image processing was executed with the help of Wolfram Mathematica software, as can be seen in Fig. 10. The algorithm used for this purpose was as follows:

- (i)

With the help of segmentation, the formerly prepared images were converted to include only black and white pixels.

- (ii)

The number of white pixels was counted in order to calculate the area of the hole (Ahole).

- (iii)

Finally, the smallest covering disk was defined as follows: the number of pixels constituting the resulting disk characterizes the disk area (Adisk). The area of burr (Aburr) was calculated as the difference between Ahole and Adisk. The burr factor (B) is expressed in the form of Eq. (3) and is applied to characterize the quality of machined holes with respect to the amount of uncut fibres.

With this novel calculation method, each hole was examined in relation to themselves. This method was necessary so that changes in the zoom ratio would not affect evaluation. Due to the microscope setup and image processing errors, burr-free holes showed a constant error of about 1–3%, especially during wobble milling.

3 Results and discussion

In this section, experimental results are analysed and discussed. First, the impact of tool geometry and drilling strategies on machining-induced damage and errors (diameter of holes, circularity error and uncut fibres) are analysed. Second, the impact of process parameters of wobble milling on machining-induced damage and errors is analysed. Finally, the results of the above-mentioned two analyses are discussed, and future trends in advanced hole machining technologies are described.

3.1 Impacts caused by tool geometry and drilling strategies

Holes of nominal diameter dn = 10 mm were machined using three different cutting tools and three different technologies. The deviation between the nominal diameter and the measured diameter by the CMM can be seen in Fig. 11 and is expressed in Eq. (4):

where dn is the nominal diameter of holes, dm is the measured diameter of holes and n is the number of experimental runs (n = 13 in the case of wobble milling, n = 3 in the case of conventional drilling and helical milling). As expected, our results show that in almost all cases, the diameters of machined holes are bigger than the nominal diameter of holes. ANOVA results show that the type of cutting tool has a significant effect (in this study ANOVA is used at a 0.05 significance level) on Dd, as can be seen in Fig. 14b. Tool C produced the biggest diameter of holes compared with tools A and B. On the other hand, no significant difference has been found as far as the effect of different drilling technologies on the diameter of holes is concerned, as can be seen in the main effects plot in Fig. 14a.

The impacts of the type of cutting tool and of drilling strategies on the circularity errors (CE) of machined holes can be seen in Fig. 12. ANOVA results show that drilling strategies have a significant effect on CE (Fig. 14c): (i) in the case of wobble milling and conventional drilling technologies, circularity errors were not larger than CE = 0.07 mm; however, (ii) in the case of helical milling strategy, the value of CE = 0.1–0.17 mm was considerably high. A possible reason for the high CE value associated with helical milling can be found in the accuracy of the CNC controller’s interpolation. Conventional drilling tool paths do not contain horizontal movements; circularity is possibly therefore lower than in the case of the other technologies under scrutiny. Furthermore, no significant difference was found in the effects of different drilling tools on CE, as illustrated in Fig. 14d.

With the help of the application of the burr factor (B) introduced above, the characteristics of uncut fibres were analysed. The impacts of the type of cutting tool and the effects of drilling strategies on the burr factor of machined holes can be seen in Fig. 13 as well as in Fig. 14e and f. It is clear from the results that the burr factor of holes machined by way of the application of wobble milling is minimal, compared with the other analysed technologies. The impacts of the type of cutting tool on burr factor were found to be negligible in the case of wobble and helical milling. However, in the case of conventional drilling strategy, the type of the applied cutting tool has a significant impact on burr factor. This could be explained by the “push-out” effect of the drilling tool on the last laminated layers of the composite. The burr area was expected to be larger in drilling operations than in the case of wobble or helical milling operations [50,51,52], because the axial cutting force (which bends the fibres at the exit of the hole) is higher during drilling.

3.2 Analysis of wobble milling

The impacts of analysed process parameters on the machined diameter of holes, on circularity error and on burr factor can be seen on Figs. 15, 16, and 17, respectively. Results of our experiments show that the effect of feed rate on the measured diameter of wobble-milled holes is small and the measured diameter is moderately influenced by the depth of cut. However, the interaction between feed rate and depth of cut is considerable. ANOVA results show that cutting tool type exerts the only significant impact on the measured diameter of holes (p value = 0.000). Concerning the diameter of machined holes, IT8 quality holes can be machined in CFRPs when wobble milling is used (calculated in line with the results of repeated experimental setups).

As shown in Fig. 16, feed rate does not exert a significant effect on the circularity error of machined holes, but the effects of the depth of cut are more considerable. Furthermore, the interaction is insignificant in the case of tools A and B. Nevertheless, interaction is more apparent in the case of tool C. CE of machined holes created by the compression end mill is lower than the CE associated with tool C. ANOVA results show that cutting tool type exerts the only significant impact on CE (p value = 0.000). For minimizing the circularity error, it is recommended to use either tool A or tool B with a small depth of cut and at any feed rate.

The impacts of feed rate and of cutting depth on burr factor can be seen in Fig. 17. Interaction is insignificant, and, in the analysed factor space, feed rate does not exert a significant effect on burr factor. ANOVA results show that cutting tool type exerts the only significant impact on burr factor (p value = 0.004). It is clear from the results that the amount of uncut fibres can be minimized on condition tool A or tool B is used. Tool C produces more uncut fibres than the other tools, but its associated burr factor is still small: not higher than B = 4%. Compared with other hole machining technologies, all of the analysed tools could produce better quality holes when wobble milling was used as compared to the use of conventional or orbital drilling. In order to minimize burr factor (~minimize the amount of uncut fibres), the use of tool A or tool B at small feed rates and at any depth of cut is recommended.

4 Discussion

In the scope of this paper, n = 57 machining experiments were carried out; thus n = 114 digital images (entry and exit side of the holes) were captured, processed and analysed. Due to the limitations of the length of this paper, a limited number of images are presented herein, and they are summarized in Fig. 19. As can be clearly seen on the figure, machining-induced macro-geometrical damage is minimal in the case of wobble milling technology. This could be achieved thanks to a proper cutting force direction setup, as shown in Fig. 1. As attested by Ahmad [3], cutting tool geometry has a significant effect on chip removal mechanisms. The cutting edges of the applied cutting tools were sharp (small cutting edge radius, positive rake and clearance angles) and exhibited good wear resistance (solid carbide tool material); the chip removal mechanisms were therefore mostly crushing-dominated. However, in the case of improper setups (e.g. first row in the figure), chip removal mechanisms become bending-dominated: fibres and matrices are bent rather than cut. Thus numerous uncut fibres and matrices are left on machined edges.

In fact, chip removal mechanism is also highly influenced by the fibre-cutting angle (ϴ – angle between the direction of fibre reinforcements and the direction of cutting speed, as defined in Fig. 18) [3]. In the case of conventional drilling, fibre-cutting angle changes between 0° and 180°. Three-dimensional drilling can be simplified, which results in a two-dimensional cutting model [25, 31, 91, 92], and thus the three-dimensional cutting of wobble milling could be simplified as well, as shown in Fig. 18. All of the four well-known UD-CFRP-related main chip removal mechanism types [55] appear during wobble milling, very similarly to conventional drilling. However, acting axial cutting forces are (i) smaller at the hole entry and (ii) press lower-lying laminated layers of the composite more powerfully during the wobble milling process. Accordingly, as opposed to the impact of the fibre-cutting angle, the applied technology (cutting tool path, tilting movement, etc.) exerts a more significant impact on the quality of the holes. In the future, chip removal mechanisms of wobble milling need more sophisticated experiments and numerical analyses in order to verify the statements and assumptions detailed in the present paper.

Conventional drilling and helical milling technologies can easily be realized and applied in industrial environments due to their moderately difficult tool paths, which also means that their operation time is low. As for circularity error and hole diameter, these technologies are appropriate, but the amount of uncut fibres on machined edges is significant, as can be seen in Fig. 19. For minimizing the amount of uncut fibres, wobble milling technology is recommended in the industry. In this case, operation time is longer, and this technology requires more prudent programming and a five-axis machine tool or industrial robots for implementation. If operation time is a significant factor, as it usually is, further optimisation of wobble milling is required.

Future directions regarding the applicability of the present research work are as follows. (i) During machining one of the most important optimisation parameters is operation time. A future goal is to shorten cycle time during wobble milling. This can be achieved by increasing the feed rate and the depth of cut. Therefore, both of these parameters have to be analysed in a wider context and wider domains (factor space) in order to optimize wobble milling processes. (ii) In the scope of this study, maximal feed rate was limited by the rotational speed of the machining centre’s rotary table. Wobble milling experiments should ideally be conducted using an industrial robot in order to eliminate such feed limitations. (iii) More advanced wobble milling algorithms should be described and examined: many tool path generation methods (spiral, cylindrical, trochoid, etc.) could be used with respect to calculating the tilt of the wobble milling cycle. (vi) The impact of wobble milling should be tested to examine the machining of hybrid composites and sandwich elements, because in that case, macro-geometrical defects could be minimized.

All in all, with the help of wobble milling, excellent quality holes can be machined: this could be a promising future technology in the aerospace industry. Furthermore, the implementation of wobble milling does not necessitate additional investments because huge CFRP parts (wings, fuselages, etc.) require industrial robots for performing associated machining tasks.

5 Conclusions

In the present study, hole machining technologies (conventional drilling, helical and wobble milling) were analysed and compared concerning CFRPs. According to the present study, the following conclusions can be drawn:

A wobble milling algorithm has been developed, discussed in detail and validated by numerous machining experiments. This newly developed algorithm is dependent on the kinematics of the machine tool or of the industrial robot used; however, the algorithm is CNC control independent.

ANOVA results (at a significance level of 0.05) show that the analysed drilling strategies have a significant effect on the circularity error (CE) of machined holes. In the case of wobble milling and conventional drilling technologies, such circularity errors are not bigger than CE = 0.07 mm. Nevertheless, in the case of helical milling strategy, CE = 0.1–0.17 mm, which is considerably high.

No significant difference has been found in the effects of the analysed drilling technologies on the diameter of holes. On the other hand, tool type has a significant impact on this value.

It has been found that the burr factor of holes machined using wobble milling is minimal in comparison with the other technologies analysed. The impact of cutting tool type on burr factor has been identified as negligible in the case of wobble and helical milling.

IT8 quality holes can be machined in CFRPs using wobble milling.

In the case of wobble milling, tool type has a significant effect on burr factor. Compared with other hole machining technologies, all of the analysed tools were able to produce better quality holes when wobble milling was used as opposed to conventional or helical milling.

In the future, additional experiments and more detailed analyses are required for optimizing wobble milling processes in order to: (i) significantly decrease operation time concurrently with an increase of feed rate, (ii) sustain and retain the good quality of machined holes and (iii) conduct numerical analyses of chip removal mechanisms during the wobble milling of UD-CFRPs.

Abbreviations

- a (mm) :

-

Cutting width

- B (%) :

-

Burr factor

- CE (mm) :

-

Circularity error

- D (mm) :

-

Hole diameter

- d (mm) :

-

Tool diameter

- ds (mm) :

-

Diameter of support hole

- dw (mm) :

-

Diameter of CFRP workpiece

- e (−) :

-

Controlled position counter

- F (mm) :

-

First value used for simplification

- h (mm) :

-

Workpiece thickness

- i (mm) :

-

Number of rotations

- n (rev/min) :

-

Spindle speed

- P (mm) :

-

Second value used for simplification

- q (°) :

-

Resolution of rotary table

- s (mm) :

-

Resultant cutting width

- t (mm) :

-

Transformed cutting width

- vf (mm/rev) :

-

Feed rate

- vc (m/min) :

-

Cutting speed

- w (mm) :

-

Vertical auxiliary value

- z (mm) :

-

Horizontal auxiliary value

- β (°) :

-

Tool rotation

- ω (°/min) :

-

Speed of rotary table

References

Forintos N, Czigany T (2019) Multifunctional application of carbon fiber reinforced polymer composites: electrical properties of the reinforcing carbon fibers – a short review. Compos Part B 162:331–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2018.10.098

Krishnaraj V, Zitoune R, Davim JP (2013) Drilling of polymer-matrix composites. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-38345-8

Ahmad J (2009) Machining of polymer composites. Springer, US. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-68619-6

Dumont F, Fröhlingsdorf W, Weimer C (2013) Virtual autoclave implementation for improved composite part quality and productivity. CEAS Aeronaut J 4:277–289. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13272-013-0072-1

Gerngross T, Nieberl D (2016) Automated manufacturing of large, three-dimensional CFRP parts from dry textiles. CEAS Aeronaut J 7:241–257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13272-016-0184-5

Gaitonde VN, Karnik SR, Rubio JC, Correia AE, Abrão AM, Davim JP (2008) Analysis of parametric influence on delamination in high-speed drilling of carbon fiber reinforced plastic composites. J Mater Process Technol 203:431–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2007.10.050

Geier N, Szalay T (2017) Optimisation of process parameters for the orbital and conventional drilling of uni-directional carbon fibre-reinforced polymers (UD-CFRP). Measurement 110:319–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2017.07.007

An Q, Ming W, Cai X, Chen M (2015) Study on the cutting mechanics characteristics of high-strength UD-CFRP laminates based on orthogonal cutting method. Compos Struct 131:374–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2015.05.035

Li H, Qin X, He G, Jin Y, Sun D, Price M (2016) Investigation of chip formation and fracture toughness in orthogonal cutting of UD-CFRP. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 82:1079–1088. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-015-7471-x

Li H, Qin X, He G, Price MA, Jin Y, Sun D (2017) An energy based force prediction method for UD-CFRP orthogonal machining. Compos Struct 159:34–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2016.09.051

Lee SC, Jeong ST, Park JN, Kim SJ, Cho GJ (2008) Study on drilling characteristics and mechanical properties of CFRP composites. Acta Mech Solida Sin 21:364–368. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10338-008-0844-z

Hintze W, Clausen R, Schütte C, Kroll K (2018) Evaluation of the total cutting force in drilling of CFRP: a novel experimental method for the analysis of the cutting mechanism. Prod Eng Res Devel 12:431–440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11740-018-0807-2

Geier N, Szalay T, Biró I (2018) Trochoid milling of carbon fibre-reinforced plastics (CFRP). Procedia CIRP 77:375–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2018.09.039

Abhishek K, Datta S, Mahapatra SS (2015) Optimization of thrust, torque, entry, and exist delamination factor during drilling of CFRP composites. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 76:401–416. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-014-6199-3

Al-wandi S, Ding S, Mo J (2017) An approach to evaluate delamination factor when drilling carbon fiber-reinforced plastics using different drill geometries: experiment and finite element study. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 93:4043–4061. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-017-0880-2

Girot F, Dau F, Gutiérrez-Orrantia ME (2017) New analytical model for delamination of CFRP during drilling. J Mater Process Technol 240:332–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2016.10.007

Heisel U, Pfeifroth T (2012) Influence of point angle on drill hole quality and machining forces when drilling CFRP. Procedia CIRP 1:471–476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2012.04.084

Melentiev R, Priarone PC, Robiglio M, Settineri L (2016) Effects of tool geometry and process parameters on delamination in CFRP drilling: An overview. Procedia CIRP 45:31–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2016.02.255

Sorrentino S, Turchetta S, Bellini C (2018) A new method to reduce delaminations during drilling of FRP laminates by feed rate control. Compos Struct 186:154–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2017.12.005

Davim JP, Reis P (2003) Study of delamination in drilling carbon fiber reinforced plastics (CFRP) using design experiments. Compos Struct 59:481–487. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0263-8223(02)00257-X

Davim JP, Reis P (2003) Drilling carbon fiber reinforced plastics manufactured by autoclave—experimental and statistical study. Mater Des 24:315–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-3069(03)00062-1

Lissek F, Tegas J, Kaufeld M (2016) Damage quantification for the machining of CFRP: An introduction about characteristic values considering shape and orientation of drilling-induced delamination. Procedia Eng 149:2–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2016.06.632

Davim JP, Rubio JC, Abrao AM (2007) A novel approach based on digital image analysis to evaluate the delamination factor after drilling composite laminates. Compos Sci Technol 67:1939–1945. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compscitech.2006.10.009

Gaugel S et al (2016) A comparative study on tool wear and laminate damage in drilling of carbon-fiber reinforced polymers (CFRP). Compos Struct 155:173–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2016.08.004

Geier N, Szalay T, Takács M (2018) Analysis of thrust force and characteristics of uncut fibres at non-conventional oriented drilling of unidirectional carbon fibre-reinforced plastic (UD-CFRP) composite laminates. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 100:3139–3154. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-018-2895-8

Ibriksz N, Geier N (2018) Analysis of uncut fibres at machined holes in carbon fibre-reinforced plastics (CFRP) using digital image processing. Bánki Rep 1:11–14

Park KM, Kurniawan R, Yu Z, Ko TJ (2019) Evaluation of a hybrid cryogenic deburring method to remove uncut fibers on carbon fiber-reinforced plastic composites. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 101:1509–1523. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-018-3045-z

Xu J, Li C, Mi S, An Q, Chen M (2018) Study of drilling-induced defects for CFRP composites using new criteria. Compos Struct 201:1076–1087. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2018.06.051

Hrechuk A, Bushlya V, Ståhl J-E (2018) Hole-quality evaluation in drilling fiber-reinforced composites. Compos Struct 204:378–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2018.07.105

Slamani M, Gauthier S, Chatelain J-F (2016) Comparison of surface roughness quality obtained by high speed CNC trimming and high speed robotic trimming for CFRP laminate. Robot Comput Integr Manuf 42:63–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcim.2016.05.004

Xu J, An Q, Chen M (2014) A comparative evaluation of polycrystalline diamond drills in drilling high-strength T800S/250F CFRP. Compos Struct 117:71–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2014.06.034

Li Z, Liu Q (2013) Surface topography and roughness in hole-making by helical milling. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 66:1415–1425. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-012-4419-2

Ashworth S et al (2019) Effects of machine stiffness and cutting tool design on the surface quality and flexural strength of edge trimmed carbon fibre reinforced polymers. Compos A: Appl Sci Manuf 119:88–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesa.2019.01.019

Chen Y, Guo X, Zhang K, Guo D, Zhou C, Gai L (2019) Study on the surface quality of CFRP machined by micro-textured milling tools. J Manuf Process 37:114–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmapro.2018.11.021

Sakamoto S, Iwasa H (2012) Effect of cutting revolution speed on cutting temperature in helical milling of CFRP composite laminates. Key Eng Mater 523–524:58–63. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/KEM.523-524.58

Jessy K, Satish kumar S, Dinakaran D, Seshagiri Rao V (2015) Influence of different cooling methods on drill temperature in drilling GFRP. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 76:609–621. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-014-6280-y

Varga G, Ravai-Nagy S, Szigeti F (2018) Examination of surface roughness of holes of plastic parts drilled under cryogenic cooling conditions. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng 448:012065. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/448/1/012065

Xia T, Kaynak Y, Arvin C, Jawahir IS (2016) Cryogenic cooling-induced process performance and surface integrity in drilling CFRP composite material. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 82:605–616. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-015-7284-y

Kerrigan K, Scaife RJ (2018) Wet vs dry CFRP drilling: influence of cutting fluid on tool performance. Procedia CIRP 77:315–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2018.09.024

Dogrusadik A, Kentli A (2017) Comparative assessment of support plates’ influences on delamination damage in micro-drilling of CFRP laminates. Compos Struct 173:156–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2017.04.031

Dogrusadik A, Kentli A (2019) Experimental investigation of support plates’ influences on tool wear in micro-drilling of CFRP laminates. J Manuf Process 38:214–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmapro.2019.01.018

Jia S, Yuan Q, Cai W, Lv J, Hu L (2018) Establishing prediction models for feeding power and material drilling power to support sustainable machining. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 100:2243–2253. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-018-2861-5

Qin X, Wang B, Wang G, Li H, Jiang Y, Zhang X (2014) Delamination analysis of the helical milling of carbon fiber-reinforced plastics by using the artificial neural network model. J Mech Sci Technol 28:713–719. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12206-013-1135-2

Wang H, Qin X, Wu D, Song A (2018) Optimization of cutting parameters in helical milling of carbon fiber reinforced polymer. Trans Tianjin Univ 24:91–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12209-017-0079-5

Liu J, Chen G, Ji C, Qin X, Li H, Ren C (2014) An investigation of workpiece temperature variation of helical milling for carbon fiber reinforced plastics (CFRP). Int J Mach Tools Manuf 86:89–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmachtools.2014.06.008

Ishida T et al (2014) Helical milling of carbon fiber reinforced plastics using ultrasonic vibration and liquid nitrogen. Procedia CIRP 24:13–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2014.07.139

Geier N, Póka G, Szalay T (2018) Direct monitoring of hole damage in carbon fibre-reinforced polymer (CFRP) composites. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng 448:012003. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/448/1/012003

Wang Q, Wu Y, Bitou T, Nomura M, Fujii T (2018) Proposal of a tilted helical milling technique for high quality hole drilling of CFRP: kinetic analysis of hole formation and material removal. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 94:4221–4235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-017-1106-3

Wang Q, Wu Y, Li Y, Lu D, Bitoh T (2018) Proposal of a tilted helical milling technique for high-quality hole drilling of CFRP: analysis of hole surface finish. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 101:1041–1049. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-018-2995-5

Schulze V, Becke C, Weidenmann K, Dietrich S (2011) Machining strategies for hole making in composites with minimal workpiece damage by directing the process forces inwards. J Mater Process Technol 211:329–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2010.10.004

Schulze V, Spomer W, Becke C (2012) A voxel-based kinematic simulation model for force analyses of complex milling operations such as wobble milling. Prod Eng Res Dev 6:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11740-011-0348-4

Schulze V, Becke C (2011) Analysis of machining strategies for fiber reinforced plastics with regard to process force direction. Procedia Eng 19:312–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2011.11.118

Davim JP, Reis P, Conceição António C (2004) Drilling fiber reinforced plastics (FRPs) manufactured by hand lay-up: influence of matrix (Viapal VUP 9731 and ATLAC 382-05). J Mater Process Technol 155–156:1828–1833. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2004.04.173

Campos Rubio J, Abrao A, Eustaquio Faria P, Esteves Correia A, Davim J (2008) Delamination in high speed drilling of carbon fiber reinforced plastic (CFRP). J Compos Mater 42:1523–1532. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021998308092205

Geier N, Davim JP, Szalay T (2019) Advanced cutting tools and technologies for drilling carbon fibre reinforced polymer (CFRP) composites: a review. Compos A: Appl Sci Manuf 125:105552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesa.2019.105552

Vigneshwaran S, Uthayakumar M, Arumugaprabu V (2018) Review on machinability of fiber reinforced polymers: a drilling approach. Silicon 10:2295–2305. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12633-018-9764-9

Abrão AM, Faria PE, Rubio JCC, Reis P, Davim JP (2007) Drilling of fiber reinforced plastics: a review. J Mater Process Technol 186:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2006.11.146

Iliescu D, Gehin D, Gutierrez ME, Girot F (2010) Modeling and tool wear in drilling of CFRP. Int J Mach Tools Manuf 50:204–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmachtools.2009.10.004

Karpat Y, Bahtiyar O (2015) Tool geometry based prediction of critical thrust force while drilling carbon fiber reinforced polymers. Adv Manuf 3:300–308. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40436-015-0129-y

Merino-Pérez JL, Royer R, Merson E, Lockwood A, Ayvar-Soberanis S, Marshall MB (2016) Influence of workpiece constituents and cutting speed on the cutting forces developed in the conventional drilling of CFRP composites. Compos Struct 140:621–629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2016.01.008

Samuel Raj D, Karunamoorthy L (2017) Cutting edge—flatting and roughness measurement—to monitor blunting and chipping of the drill cutting edge when drilling CFRP. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 92:953–968. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-017-0090-y

Li M, Soo SL, Aspinwall DK, Pearson D, Leahy W (2018) Study on tool wear and workpiece surface integrity following drilling of CFRP laminates with variable feed rate strategy. Procedia CIRP 71:407–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2018.05.055

Hrechuk A, Bushlya V, M’Saoubi R, Ståhl J-E (2018) Experimental investigations into tool wear of drilling CFRP. Procedia Manuf 25:294–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.promfg.2018.06.086

Wang C-Y, Chen Y-H, An Q-L, Cai X-J, Ming W-W, Chen M (2015) Drilling temperature and hole quality in drilling of CFRP/aluminum stacks using diamond coated drill. Int J Precis Eng Manuf 16:1689–1697. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12541-015-0222-y

Zhang L, Liu Z, Tian W, Liao W (2015) Experimental studies on the performance of different structure tools in drilling CFRP/Al alloy stacks. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 81:241–251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-015-6955-z

Lin SC, Chen IK (1996) Drilling carbon fiber-reinforced composite material at high speed. Wear 194:156–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/0043-1648(95)06831-7

Durão LMP, Gonçalves DJS, Tavares JMRS, de Albuquerque VHC, Aguiar Vieira A, Torres Marques A (2010) Drilling tool geometry evaluation for reinforced composite laminates. Compos Struct 92:1545–1550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2009.10.035

Feito N, Álvarez JD, Cantero JL, Miguélez MH (2015) Influence of special tool geometry in drilling woven CFRPs materials. Procedia Eng 132:632–638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2015.12.541

Su F, Zheng L, Sun F, Wang Z, Deng Z, Qiu X (2018) Novel drill bit based on the step-control scheme for reducing the CFRP delamination. J Mater Process Technol 262:157–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2018.06.037

Xu J, Li C, Chen M, El Mansori M, Ren F (2019) An investigation of drilling high-strength CFRP composites using specialized drills. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 103:3425–3442. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-019-03753-8

Su F, Wang Z, Yuan J, Cheng Y (2015) Study of thrust forces and delamination in drilling carbon-reinforced plastics (CFRPs) using a tapered drill-reamer. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 80:1457–1469. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-015-7124-0

Grilo TJ, Paulo RMF, Silva CRM, Davim JP (2013) Experimental delamination analyses of CFRPs using different drill geometries. Compos Part B Eng 45:1344–1350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2012.07.057

Xu J, An Q, Cai X, Chen M (2013) Drilling machinability evaluation on new developed high-strength T800S/250F CFRP laminates. Int J Precis Eng Manuf 14:1687–1696. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12541-013-0252-2

Shyha IS, Aspinwall DK, Soo SL, Bradley S (2009) Drill geometry and operating effects when cutting small diameter holes in CFRP. Int J Mach Tools Manuf 49:1008–1014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmachtools.2009.05.009

Feito N, Díaz-Álvarez J, López-Puente J, Miguelez MH (2018) Experimental and numerical analysis of step drill bit performance when drilling woven CFRPs. Compos Struct 184:1147–1155

Lissek F, Kaufeld M, Bergmann J P (2014) Machining of cfrp: drilling and milling of unstable work pieces 58:14. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:gbv:ilm1-2014iwk-065:3

Feito N, Diaz-Álvarez J, López-Puente J, Miguelez MH (2016) Numerical analysis of the influence of tool wear and special cutting geometry when drilling woven CFRPs. Compos Struct 138:285–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2015.11.065

Qiu X, Li P, Niu Q, Chen A, Ouyang P, Li C, Ko TJ (2018) Influence of machining parameters and tool structure on cutting force and hole wall damage in drilling CFRP with stepped drills. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 97:857–865. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-018-1981-2

Tsao CC (2008) Prediction of thrust force of step drill in drilling composite material by Taguchi method and radial basis function network. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 36:11–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-006-0808-8

Qiu X et al (2018) Study on chisel edge drilling behavior and step drill structure on delamination in drilling CFRP. Compos Struct 203:404–413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2018.07.007

Yuan S, Zhang C, Amin M, Fan H, Liu M (2015) Development of a cutting force prediction model based on brittle fracture for carbon fiber reinforced polymers for rotary ultrasonic drilling. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 81:1223–1231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-015-7269-x

Tsao CC (2007) Taguchi analysis of drilling quality associated with core drill in drilling of composite material. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 32:877–884. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-006-0414-9

Tsao CC (2008) Comparison between response surface methodology and radial basis function network for core-center drill in drilling composite materials. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 37:1061–1068. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-007-1057-1

Tsao CC, Chiu YC (2011) Evaluation of drilling parameters on thrust force in drilling carbon fiber reinforced plastic (CFRP) composite laminates using compound core-special drills. Int J Mach Tools Manuf 51:740–744. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmachtools.2011.05.004

Tsao CC (2008) Thrust force and delamination of core-saw drill during drilling of carbon fiber reinforced plastics (CFRP). Int J Adv Manuf Technol 37:23–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-007-0963-6

Voss R, Henerichs M, Kuster F (2016) Comparison of conventional drilling and orbital drilling in machining carbon fibre reinforced plastics (CFRP). CIRP Ann 65:137–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cirp.2016.04.001

Brinksmeier E, Fangmann S, Meyer I (2008) Orbital drilling kinematics. Prod Eng 2:277–283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11740-008-0111-7

Cheng X, Zhang X, Tian Y, Zheng G, Yang X (2018) Study on micro helical milling of small holes with flat end mills. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 97:3119–3128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-018-2187-3

Haiyan W, Xuda Q (2016) A mechanistic model for cutting force in helical milling of carbon fiber-reinforced polymers. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 82:1485–1494. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-015-7460-0

Chakravorty P (2018) What is a signal? [lecture notes]. IEEE Signal Process Mag 35:175–177. https://doi.org/10.1109/MSP.2018.2832195

Voss R, Seeholzer L, Kuster F, Wegener K (2017) Influence of fibre orientation, tool geometry and process parameters on surface quality in milling of CFRP. CIRP J Manuf Sci Technol 18:75–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cirpj.2016.10.002

Hintze W, Hartmann D, Schütte C (2011) Occurrence and propagation of delamination during the machining of carbon fibre reinforced plastics (CFRPs) – An experimental study. Compos Sci Technol 71:1719–1726. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compscitech.2011.08.002

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Budapest University of Technology and Economics (BME). This research was partly supported by the project “Centre of Excellence in Production Informatics and Control” (EPIC) No. EU H2020-WIDESPREAD-01-2016-2017-TeamingPhase2-739592. The research work introduced herein was partly supported by the Higher Education Excellence Program of the Hungarian Ministry of Human Capacities as part of Budapest University of Technology and Economics’ (BME FIKP-NANO) research field “Nanotechnology and Material Science” and was also supported by Project No. 2018-2.1.15-TÉT-PT-2018-00012.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pereszlai, C., Geier, N. Comparative analysis of wobble milling, helical milling and conventional drilling of CFRPs. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 106, 3913–3930 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-019-04842-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-019-04842-4