Abstract

We present evidence for two mechanisms that can explain increasing geographic divide of partisan preferences. The first is “inadvertent sorting,” where people express a preference for residential environments with features that just happen to be correlated with partisanship. The second is “intentional sorting,” where people do consider partisanship directly. We argue that the accumulating political biases visible in many neighborhoods can be the effect of some mixture of these two mechanisms. Because residential relocation often involves practical constraints and neighborhood racial composition is more important than partisanship, there is less partisan segregation across the USA than there could be based on residential preference alone.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

YouGov. Palo Alto, California. https://today.yougov.com/about/, accessed July 8, 2016.

For sampling design of the CCES surveys and a list of studies published using these surveys, see http://projects.iq.harvard.edu/cces/home.

The descriptive statistics for these nine items are presented in Fig. 7 of “Appendix.”

Specifically, we estimated the model using the R package, poLCA. Similar to other kinds of clustering techniques, deciding on the number of groups poses the most challenging empirical decision. Based on our judgement, we decided on the four-group model by reading through all summary statistics, including a conditional item response probabilities matrix, latent class regression results and distribution of predicted classes. We decided that four groups make the more intuitive sense than three groups as the additional class separates the “no opinion” respondents from those who hold mixed or ambivalent views.

Zip codes are a system of postal codes used by the US Postal service to deliver mails efficiently. According to mapszipcode.com, there are about 33,000 zip codes in the USA. The smallest zip code is only 0.0032 square miles and the largest one is 13,431 square miles. The average land area of a zip code is about 90 square miles. Population across zip codes varies significantly. The most populated zip code in Puerto Rico has over 144,000 residents and the smallest zip code in Montana only has one resident. An average zip code has about 7600 residents.

We obtained the zip code-level data from this site: http://blog.splitwise.com/2014/01/06/free-us-population-density-and-unemployment-rate-by-zip-code/.

Our respondents for our two YouGov surveys are spread out geographically with a majority residing in densely populated zip codes in cities and suburbs. In our sample, over 90% of the zip codes only have a single respondent. About 8% of zip codes have between two and three respondents. The most “populated” zip code, 97701, has four respondents. Because we have slightly fewer than 2000 respondents scattered across fifty states, there are insufficient cases to conduct within state analyses. In addition, because we have very few respondents within each zip code, the responses are not representative at the zip code level and cannot be used to conduct reliable spatial analyses.

References

Abrams S, Fiorina M (2012) The myth of the ‘big sort’. Issue 3. Hoover Digest, Washington, DC

Akerlof GA, Kranton RE (2000) Economics and identity. Q J Econ 115(3):715–753

Anacker KB, Morrow-Jones HA (2005) Neighborhood factors associated with same-sex households in US cities. Urban Geogr 26(5):385–409

Ansolabehere S, Rodden J, Snyder J (2006) Purple America. J Econ Perspect 20(2):97–118

Ansolabehere S, Rivers D (2013) Cooperative survey research. Annu Rev Polit Sci 16:307–329

Ansolabehere S, Schaffner BF (2014) Does survey mode still matter? Findings from a 2010 multi-mode comparison. Polit Anal 22(3):285–303

Badger E, Bui Q, Pearce A (2016) The election highlighted a growing rural–urban split. New York Times, November 11, The Upshot. http://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/12/upshot/this-election-highlighted-a-growing-rural-urban-split.html?_r=0. Accessed 1 Dec 2016

Bakshy E, Messing S, Adamic LA (2015) Exposure to ideologically diverse news and opinion on Facebook. Science 348(6239):1130–1132

Bishop B (2009) The big sort: why the clustering of like-minded America is tearing us apart. Houghton Mifflin, New York

Blair G, Imai K (2012) Statistical analysis of list experiments. Polit Anal 20:47–77

Blair G, Imai K, Lyall J (2014) Comparing and combining list and endorsement experiments: evidence from Afghanistan. Am J Polit Sci 58(4):1043–1063

Blanchard TC (2007) Conservative protestant congregations and racial residential segregation: evaluating the closed community thesis in metropolitan and nonmetropolitan counties. Am Sociol Rev 72(3):416–433

Brunner E, Ross SL, Washington E (2011) Economics and policy preferences: causal evidence of the impact of economic conditions on support for redistribution and other ballot proposals. Rev Econ Stat 93(3):888–906

Cadwallader MT (1992) Migration and residential mobility: macro and micro approaches. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison

Campbell A, Converse PE, Miller WE, Stokes DE (1960) The American voter. Wiley, New York

Cho WKT, Gimpel JG, Hui IS (2013) Voter migration and the geographic sorting of the American electorate. Ann Assoc Am Geogr 103(4):856–870

Chopik WJ, Motyl M (2016) Ideological fit enhances interpersonal orientations. Soc Psychol Personal Sci (Forthcoming)

Clark WAV (2012) Residential mobility and the housing market. The SAGE handbook of housing studies. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, pp 66–83

Clark WAV, Deurloo M, Dieleman F (2006) Residential mobility and neighbourhood outcomes. Hous Stud 21(3):323–342

Corstange D (2009) Sensitive questions, truthful answers? Modeling the list experiment with LISTIT. Polit Anal 17(1):45–63

Crowder K, South SJ (2008) Spatial dynamics of white flight: the effects of local and extralocal racial conditions on neighborhood out-migration. Am Sociol Rev 73(5):792–812

Crowder K, Hall M, Tolnay SE (2011) Neighborhood immigration and native out-migration. Am Sociol Rev 76(1):25–47

Emerson MO, Chai KJ, Yancey G (2001) Does race matter in residential segregation? Exploring the preferences of white Americans. Am Sociol Rev 66(6):922–935

Fischer CS (1995) The subcultural theory of urbanism: a twentieth-year assessment. Am J Sociol 101(3):543–577

Florida R (2002) The economic geography of talent. Ann Assoc Am Geogr 92(4):743–755

Florida R, Mellander C (2010) There goes the metro: how and why bohemians, artists and gays affect regional housing values. J Econ Geogr 10(2):167–188

Fisher RJ (1993) Social desirability bias and the validity of indirect questioning. J Consum Res 20(2):303–315

Fox J (2003) Effect displays in R for generalized linear models. J Stat Softw 8(15):1–27

Fry R, Taylor P (2012) The rise of residential segregation by income. Pew Research Center, Washington, DC

Gallego A, Buscha F, Sturgis P, Oberski D (2016) Places and preferences: a longitudinal analysis of self-selection and contextual effects. Br J Polit Sci 46(3):529–550

Gilbert C (2014) Democratic republican voters worlds apart in divided Wisconsin. Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel. http://www.jsonline.com/news/statepolitics/democratic-republican-voters-worlds-apart-in-divided-wisconsin-b99249564z1-255883361.html

Giddens A (1991) Modernity and self-identity: self and society in the late modern age. Polity Press, Cambridge

Gimpel JG, Karnes KA (2006) The rural side of the urban-rural gap. PS Polit Sci Polit 39(3):467–472

Glynn AN (2013) What can we learn with statistical truth serum? Design and analysis of the list experiment. Public Opin Q 77(S1):159–172

Golman R, Loewenstein G, Moene KO, Zarri L (2016) The preference for belief consonance. J Econ Perspect 30(3):1–14

Green D, Palmquist B, Schickler E (2002) Partisan hearts and minds: political parties and the social identities of voters. Yale University Press, New Haven

Greenwood MJ (1975) Research on internal migration in the United States: a survey. J Econ Lit 13:397–433

Harton HC, Bullock M (2007) Dynamic social impact: a theory of the origins and evolution of culture. Soc Personal Psychol Compass 1(1):521–540

Hedman L (2011) The impact of residential mobility on measurements of neighbourhood effects. Hous Stud 26(4):501–519

Hillygus DS, Jackson N, Young M (2014) Professional respondents in non-probability online panels. In: Callegaro M et al (eds) Online panel research: a data quality perspective. Wiley, Chichester, pp 219–237

Honneth A (2004) Organized self-realization some paradoxes of individualization. Eur J Soc Theory 7(4):463–478

Huckfeldt R (1986) Politics in context. Agathon, New York

Huckfeldt R, Sprague J (1995) Citizens, politics and social communication: information and influence in an election campaign. Cambridge University Press, New York

Huckfeldt R (2014) Networks, contexts, the combinatorial dynamics of democratic politics. Adv Polit Psychol 35(S1):43–68

Hui I (2013) Who is your preferred neighbor? Partisan residential preferences and neighborhood satisfaction. Am Polit Res 41(6):997–1021

Iyengar S, Westwood SJ (2015) Fear and loathing across party lines: new evidence on group polarization. Am J Polit sci 59(3):690–707

Kinsella C, McTague C, Raleigh KN (2015) Unmasking geographic polarization and clustering: a micro-scalar analysis of partisan voting behavior. Appl Geogr 62(3):404–419

Klofstad C, McClurg SD, Rolfe M (2009) Measurement of political discussion networks: a comparison of two ‘name generator’ procedures. Public Opin Q 73(3):462–483

Krysan M, Couper MP, Farley R, Forman T (2009) Does race matter in neighborhood preferences? Results from a video experiment. Am J Sociol 115(2):527

Kuklinski J, Cobb M, Gilens M (1997a) Racial attitudes and the New South. J Polit 59(2):323–349

Kuklinski J, Sniderman P, Knight K, Piazza T, Tetlock P, Lawrence G, Mellers B (1997b) Racial prejudice and attitudes toward affirmative action. Am J Polit Sci 41(2):402–419

Lang C, Pearson-Merkowitz S (2015) Partisan sorting in the United States, 1972–2012: new evidence from a dynamic analysis. Polit Geogr 49:31–44

Lavrakas PJ (2008) Encyclopedia of survey research methods. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks

Latané B, Liu JH (1996) The intersubjective geometry of social space. J Commun 46(4):26–34

Lee BA, Matthews SA, Iceland J, Firebaugh G (2015) Residential inequality orientation and overview. Ann Am Acad Polit Soc Sci 660(1):8–16

Linzer DA, Lewis JB (2011) poLCA: an R package for polytomous variable latent class analysis. J Stat Softw 42(10):1–29

Long L (1988) Migration and residential mobility in the United States. Russell Sage Foundation, New York

McDonald I (2011) Migration and sorting in the American electorate: evidence from the 2006 cooperative congressional election study. Am Polit Res 39(3):512–533

McKee SC, Teigen JM (2009) Probing the reds and blues: sectionalism and voter location in the 2000 and 2004 US presidential elections. Polit Geogr 28(8):484–495

McPherson M, Smith-Lovin L, Cook JM (2001) Birds of a feather: homophily in social networks. Annu Rev Sociol 27:415–444

Mummolo J, Nall C (2016) Why partisans don’t sort: the constraints on political segregation. Paper draft. http://web.stanford.edu/~nall/docs/gaweb.pdf. Accessed 1 Dec 2016

Motyl M (2014) Liberals and conservatives are (geographically) dividing. In: Valdesolo P, Graham J (eds) Bridging ideological divides: the Claremont symposium for applied social psychology. Sage Press, Thousand Oaks

Motyl M, Iyer R, Oishi S, Trawalter S, Nosek BA (2014) How ideological migration geographically segregates groups. J Exp Soc Psychol 51:1–14

Myers AS (2013) Secular geographic polarization in the American South: the case of Texas, 1996–2010. Elect Stud 32(1):48–62

Mutz D (2006) Hearing the other side: deliberative versus participatory democracy. Cambridge University Press, New York

Oakes JM (2004) The (mis) estimation of neighborhood effects: causal inference for a practicable social epidemiology. Soc Sci Med 58(10):1929–1952

Oishi S, Miao FF, Kisling J, Koo M, Ratliff KA (2012) Residential mobility breeds familiarity-seeking. J Personal Soc Psychol 102(1):149–162

Reardon SF, Bischoff K (2011) Income inequality and income segregation. Am J Sociol 116(4):1092–1153

Rivers D, Bailey D (2009) Inference from matched samples in the 2008 US national elections. In: Proceedings of the joint statistical meetings, pp 627–639

Rossi PH (1955) Why families move. The Free Press, Glencoe

Rossi PH, Shlay AB (1982) Residential mobility and public policy issues: ‘why families move’ revisited. J Soc Issues 38(3):21–34

Sampson RJ, Morenoff JD, Gannon-Rowley T (2002) Assessing ‘neighborhood effects’: social processes and new directions in research. Annu Rev Sociol 28:443–478

Sampson RJ (2011) Neighborhood effects, causal mechanisms and the social structure of the city. Chapter 11. In: Demeulenaere P (ed) Analytical sociology and social mechanisms. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp 227–249

Schelling TC (1971) Dynamic models of segregation. J Math Sociol 1(2):143–186

Sharkey P (2012) Residential mobility and the reproduction of unequal neighborhoods. Cityscape 14(3):9–31

Slater D (1997) Consumer culture and modernity. Polity Press, Cambridge

Sussell J (2013) New support for the big sort hypothesis: an assessment of partisan geographic sorting in California, 1992–2010. PS Polit Sci Polit 46(4):768–773

Tiebout CM (1956) A pure theory of local expenditures. J Polit Econ 64(5):416–424

Vavreck L, Rivers D (2008) The 2006 cooperative congressional election study. J Elect Public Opin Parties 18(4):355–366

Vigdor JL (2006) Fifty million voters can’t be wrong: economic self-interest and redistributive politics, (No. w12371). National Bureau of Economic Research. SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=918969

Walker KE (2013) Political segregation of the metropolis: spatial sorting by partisan voting in metropolitan Minneapolis-St Paul. City Commun 12(1):35–55

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

See Tables 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and Fig. 7.

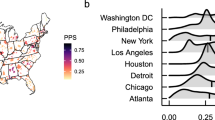

Average responses to the nine place preference items. Note: the five-point Likert scale is recoded where \(-2\) and \(-1\) indicate “strongly disagree” and “disagree”; zero indicates neutral position and “agree” and “strongly agree” are coded 1 and 2. The dots represent the sample averages and the symbols (“D”, “R”) show the means among Democratic and Republican identifiers. Democrats, on average, have more favorable impression of big cities than Republicans