Abstract

This paper newly introduces sequential entry into previous models of spatial price discrimination that examine location choices made in anticipation of a potential merger. While merger with simultaneous entry routinely reduces social welfare, we show that mergers frequently improve welfare. The extent of welfare improving mergers varies inversely with the timing advantage of an excluded rival. When the rival locates alone in the first stage, the merger harms welfare. When the rival locates alone in the last stage, the merger improves welfare. These results hold true when allocating three firms across either two or three location stages. Thus, allowing staged entry dramatically alters and often reverses the conclusion previously drawn on the basis of simultaneous entry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

One further assumption is that the production is characterized by constant marginal cost as Gupta (1994) shows that when production is characterized by increasing marginal cost, firms will not locate efficiently. As a consequence, the welfare implications of merger in an otherwise equal case of increasing marginal production cost remain unclear and unexamined.

We note that Rothschild et al. (2007) consider a sequential entry model with spatial price discrimination in which firms merge prior to location choices (or make binding side payments prior to location choices). Thus, the merged firm locates two plants so as to limit the market of an excluded rival. While this model recognizes the timing advantage associated with sequential entry, it reverses the traditional game structure of non-cooperative location decisions happening prior to (but in expectation) of a subsequent merger.

Thus, airline flights between city pairs differ by departure time from early morning to late evening, the editorial policies of newspapers differ from liberal left to conservative right, and breakfast cereals differ in their sugar content.

When relaxing the assumption that \(\alpha =1/2\), it continues to be the case that for any merger that happens, welfare will fall. However, for either very large or very small values of \(\alpha \), one of the merging firms losses profit with the merger, and so it will not go forward.

As with the two-stage location game, if the second entrant retain a larger share of the incremental profit from merger, it is possible to have a profitable merger (cite).

The middle firm is more likely to jump since it does not have the extra corner profit of the other follower. Thus, the no-jump condition from the middle firm binds rather than that from the firm in the right corner.

References

Farrell J, Shapiro C (1990) Horizontal mergers: an equilibrium analysis. Am Econ Rev 80:107–126

Greenhut ML (1981) Spatial pricing in the United States, West Germany and Japan. Economica 48:79–86

Gupta B (1992) Sequential entry and deterrence with competitive spatial price discrimination. Econ Lett 38:487–490

Gupta B (1994) Competitive spatial price discrimination with strictly convex production costs. Reg Sci Urban Econ 24:265–272

Gupta B, Heywood JS, Pal D (1997) Duopoly, delivered pricing and horizontal mergers. South Econ J 63:585–593

Heywood J, Ye G (2009) Mixed oligopoly, sequential entry, and spatial price discrimination. Econ Inq 47:589–597

Heywood J, Ye G (2011a) Patent licensing in a model of spatial price discrimination. In: Papers in regional science, vol 90, pp 589–602

Heywood J, Ye G (2011b) Sequential entry and merger in spatial price discrimination. Working Paper, Department of Economics, University of Wisconsin—Milwaukee

Heywood J, Monaco K, Rothschild R (2001) Spatial price discrimination and merger: the N firm case. South Econ J 67:672–685

Lederer P, Hurter A (1986) Competition of firms: discriminatory pricing and location. Econometrica 54:623–640

McAfee RP, Simmons JJ, Williams M (1992) Horizontal mergers in spatially differentiated non-cooperative markets. J Ind Econ 40:349–358

Monaco K, Heywood JS, Rothschild R (2004) Delivered pricing and merger with demand constraints. Econ Inq 42:49–59

Posada P, Straume OR (2004) Merger, partial collusion and relocation. J Econ 83:243–265

Prescott E, Visscher M (1977) Sequential location among firms with foresight. Bell J Econ 8:378–393

Qiu LD, Zhou W (2007) Merger waves: a model of endogenous mergers. Rand J Econ 38:214–226

Reitzes J, Levy D (1995) Price discrimination and merger. Can J Econ 28:427–436

Rothschild R, Heywood J, Monaco K (2000) Spatial price discrimination and the merger paradox. Reg Sci Urban Econ 30:491–506

Rothschild R, Heywood J, Monaco K (2007) Strategic contracts versus multiple plants: location under sequential entry. Manch School 75:237–257

Salant S, Switzer S, Reynolds R (1983) Losses from horizontal merger: the effects of an exogenous change in industry structure on cournot-nash equilibrium. Q J Econ 298:185–213

Thisse J, Vives X (1988) On the strategic choice of spatial price policy. Am Econ Rev 78:122–137

Tirole J (1988) The theory of industrial organization. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

Acknowledgments

Ye thanks the Fundamental Research Fund of Renmin University of China, and the Program of New Century Excellent Talents in University for Central Universities for Support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: The benchmark cases without merger in two-stage entry

In this section, we identify the locations and welfare from two benchmark cases without the possibility of merger.

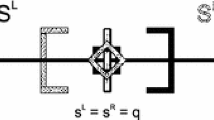

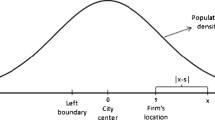

1.1 Benchmark case 1: One firm enters in stage one

A profit maximizing first entrant locates at the corner, and we assign it \(L_1 \). The two followers’ best responses in terms of leader’s location are

Thus, the profit of the firm in the middle becomes \(\pi _2 =\frac{2(1-L_1)^{2}t}{25}\). In order to maintain its profitable corner location, the leader must locate such that no firm earns greater profit locating on its left (the “no jump condition”). The profit of firm 2 if it jumps to the leader’s left corner is \(\pi _2^j =\frac{(L_1)^{2}t}{3}\).Footnote 6 The no jump condition requires that this profit just equal that when it is in the middle, \(\pi _2^ =\pi _2^j \). This implies that \(L_1^{2j} =0.329\). The unconstrained profit maximization, \(L^u =\frac{4}{9}\), is such that \(L_1^u \ge L_1^j \). Thus, the no-jump condition implies the equilibrium locations:

The profit and welfare of the three firms follow immediately:

This result exactly mimics Heywood and Ye (2009) when \(n=3\).

1.2 Benchmark case 2: Two firms enter in stage 1

When two firms enter in stage one, each locates at a corner to obtain the extra profit. They also move toward the center as much as possible such that firm 2 (in stage two) is indifferent between locating in the middle and jumping to a corner. The symmetry of two leaders implies that \(L_1=1-L_3 \) and firm 2 maximizes profit at \(L_2 =\frac{L_1+L_3 }{2}\). The no-jump condition equates the profit of this middle location, \(\pi _2 =\frac{(1-2L_1)^{2}t}{8}\), with that if it jumped, \(\pi _2^j =\frac{(L_1)^{2}t}{3}\). This implies that

Firms’ profit and welfare are

This result exactly mimics Gupta (1992).

Appendix 2: The benchmark case without merger in three stage entry

In this section, we identify the locations and welfare from the benchmark case without the possibility of merger. When first two firms have timing advantage, each locates at a corner to obtain the extra profit. They also move toward the center as much as possible such that the third firm is indifferent between locating in the middle and jumping to a corner. The symmetry of two early movers implies that \(L_1 =1-L_2 \), and the middle firm maximizes profit at \(L_3 =\frac{L_1^ +L_2 }{2}\). The no-jump condition equates the profit of the third firm in the middle, \(\pi _3 =\frac{(1-2L_1 )^{2}t}{8}\), with that if it jumped, \(\pi _3^j =\frac{(L_1)^{2}t}{3}\). This implies that

Please note that subscripts denote the timing of firms in the rest of this paper, and thus, firm 3 may locate on the left to firm 2. Firms’ profit and welfare are

This result exactly mimics Gupta (1992). We will now examine the three possible divisions of our firms comparing each possibility with merger to the relevant benchmark.