Abstract

We investigate the impact of exposure to an economically deprived neighborhood in Denmark on outcomes related to mental health. To identify the effect, we exploit the quasi-random assignment of applicants to diverse neighborhoods by the Copenhagen municipality from 2000 to 2007. Using data on the assignment combined with longitudinal administrative data, we find that exposure to an economically deprived neighborhood significantly increases the probability of being treated with psychiatric medication by 3.6 percentage points. A significant negative impact on mental health occurs among men and non-Western immigrants, and the results indicate that the effect of neighborhood deprivation on mental health is cumulative. We find that the negative impact of neighborhood deprivation comes from the most deprived neighborhoods. Our results suggest that for vulnerable populations, exposure to deprived neighborhoods affects mental health through social interactions with their new neighbors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Treated with psychiatric medication encompasses those bearing the following Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical codes: N05A, N05B, N05C, N06A (except N06Ax12), N06B, N07B, and N02.

Another structural factor is macroeconomic shocks. We consider such shocks to be less important in our context, because we estimated the neighborhood effects on individuals who were living in the same municipality and thus were affected by the same policies and economic conditions.

In the MTO experiment, the compliance rate was 47% (Sanbonmatsu et al. 2011).

People are defined as non-employed if they receive social assistance, a disability pension, or unemployment benefits in November of a given year.

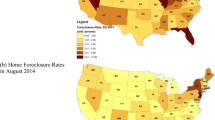

Electronic Supplementary Material Fig. 4 shows the location of deprived neighborhoods within the postal code areas.

Although, technically, applicants could apply twice, our dataset provides information on the final housing offer only. This can potentially bias the results if the probability of declining the first housing offer is related to the applicants’ mental health and the neighborhood of the assigned apartment. However, it is not clear, a priori, how acceptance of the final offer would bias the results. While those with better mental health might be less likely to accept the first offer because they are able to wait for a better offer, the vulnerable group of applicants also includes applicants who at the time of assignment are unable to accept the offer and therefore get moved back in the queue and have to wait for a new offer (Anker et al. 2002). Thus the question of bias relies on the balance test that we present in Section 5.1.

When we compare the share of applicants using psychiatric medication five years before and after the assignment for the groups that move and do not move into the assigned apartment, we find no significant differences and no systematic pattern. These results are available upon request.

Among applicants who had not been treated with psychiatric medication during the five years before the assignment, 31% of those assigned to non-deprived neighborhoods and 33% of those assigned to deprived neighborhoods changed GPs after the assignment. These percentages are statistically insignificant.

Housing blocks (in Danish, afdelinger) are usually of the same building material and were constructed during the same period. Housing block construction is initiated by a housing association and is approved and supported by the municipality. Selected tenants from the housing block form a board that is responsible for maintaining and managing internal issues, such as hiring janitors (Scanlon and Vestergaard 2007).

In a recent Danish study by (Hjorth et al. 2016), respondents were asked to draw their self-perceived neighborhood on maps. Combining this data with administrative registry data, Hjorth et al. found that the median size of a neighborhood is 479 residents.

Studies based on the MTO experiment have defined a deprived neighborhood as an area with where the share of income-poor residents is at least 40% (Chetty et al. 2016; Jacob et al. 2013; Katz et al. 2001; Kling et al. 2007; Leventhal and Brooks-Gunn 2003b; Ludwig et al. 2013). Oreopoulos (2003) used a similar approach in Canada.

Several other studies characterize deprived neighborhoods by using a combination of neighborhood characteristics, such as the unemployment rate, percentage of residents having only primary education, the poverty rate, and female head of households (Iversen et al. 2019; Kauppinen 2007; Wodtke et al. 2011).

Gross income includes all taxable income, which in Denmark includes earned income, welfare benefits, and income derived from investments. The highest quartile of the non-employment rate corresponds to 45% or higher of non-employed residents, whereas the lowest quartile of the gross income distribution corresponds to the average maximum annual earning of Danish Kroner (DKK) 188,359 (USD $30,778), measured in 2014 prices.

Analyses on assignment data from 2008 through 2013 support the conclusion that after 2007 the assignment process became less random. These results are available from the authors upon request.

In data, we observe that 76 applicants had more than one assigned address (which they accepted) in the same year. We do not know the reason for having two assignments in the same year. We included these 76 applicants in the analytical sample using their last assigned address. The results are the same when we use the first assigned address.

The PSH office assigns apartments to immigrant households, most of whom did not live in Denmark in all five of the five years prior to the assignment. For these households, we do not have health records five years before the assignment. However, observation in the sample of less than five years before the assignment is not correlated with the probability of being assigned to a deprived neighborhood (p value of 0.804). These results are available upon request.

Very few applicants are above 60 years.

Non-employed includes individuals receiving unemployment benefits, social assistance, or early retirement benefits. Convicted of crime(s) includes convicted of violating criminal laws, firearm or narcotics control laws, or some combination of these. Admitted to psychiatric hospital encompasses those bearing the following primary diagnosis code of the International Classification of Diseases: F20, F24, F25, F28, F319, F323, and F333. Admitted to somatic hospital encompasses those with the following primary diagnoses: cancer, stroke, heart attack, and high blood pressure.

In Denmark, a parish is a small administrative district based on a historical ecclesiastical teritory. Today, the parish boundaries function as ecclesiastical regions, school districts, and natural boundaries for community associations.

Brueckner and Rosenthal (2009) use the year of construction of the housing stock as a proxy for the quality of housing.

We estimated this model using the ten nearest neighbors including the full list of control variables. To do this, we applied Leuven and Sianesi’s Stata module psmatch 2 (Leuven and Sianesi 2003). An examination of the propensity score with and without matching reveals that treatment and control groups are very similar on observables regardless of the type of matching.

We have tested various specifications of this model. First, we have tested the model including individual characteristics measured two to five years before assignment. Second, we have tested the model with various ex ante health indicators, e.g., lagged variables for treatment with antidepressants, and for hospitalization due to a severe mental illness for the applicants and family members. The results from these models are virtually the same.

We find no differences between households assigned to deprived or non-deprived neighborhoods due to affordable rent (as specified by the applicant) and the reported house rent per square meter (these results are available upon request). We suggest that these results are attributable to the empirically observed insignificant association between household income and the probability of being assigned to a deprived neighborhood (see table 2).

We find no significant differences in the average pre-neighborhood characteristics for applicants assigned to deprived and non-deprived neighborhoods (see Electronic Supplementary Material Table 6).

Although the parameter estimate on being a non-Western immigrant regressed on the percentage of non-Western immigrants in the neighborhood is significant, the estimate is relatively small and negative (− 0.003).

In the full sample, 31.4% were treated with psychiatric medication the year before they were assigned housing by the PSH office, thus, the translated effect size is: (1 − ((0.036 + 0.314)/0.314)) × 100 = 11.5%.

The difference in the point estimates for men and women in Table 4 is statically significant at the 10 percent level (t-value of 1.7). The difference in the point estimates for Danes and Western and non-Western immigrants is not statistically significant (t-value of 1.1).

We also tested the impact of being assigned to a deprived neighborhood by mental health status, i.e., whether the applicant was a user of psychiatric medication up to 5 years before assignment. The parameter estimate is 0.026 and 0.028 for users and non-users, respectively, and is insignificant for both groups.

References

Abadie A, Athey S, Imbens GW, Wooldridge J (2017) When should you adjust standard errors for clustering? (Working Paper Nr. 24003). Natl Bur Econ Res. https://doi.org/10.3386/w24003

Angrist JD, Pischke JS (2008) Mostly harmless econometrics: an empiricist’s companion. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey

Anker J, Christensen I, Skovgaard Romose T, Børner Stax T (2002) Kommunal Boliganvisning til Almene Familieboliger: En Analyse af Praksis og Politik i Fire Kommuner. (Working Paper Nr. 24:2002). Danish Natl Inst Soc Res. https://www.vive.dk/media/pure/6170/350856. Accessed 9 Nov 2021

Åslund O, Edin PA, Fredriksson P, Grönqvist H (2011) Peers, neighborhoods, and immigrant student achievement: evidence from a placement policy. Am Econ J Appl Econ 3(2):67–95. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.3.2.67

Awaworyi Churchill S, Farrell L, Smyth R (2019) Neighbourhood ethnic diversity and mental health in Australia. Health Econ 28(9):1075–1087. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.3928

Baltagi BH (2008) Econometric analysis of panel data. John Wiley & Sons Ltd., Chichester

Bayer P, Sl R, Topa G (2008) Place of work and place of residence: informal hiring networks and labor market outcomes. J Polit Econ 116(6):1150–1196. https://doi.org/10.1086/595975

Beaman LA (2012) Social networks and the dynamics of labour market outcomes: evidence from refugees resettled in the U.S. Rev Econ Stud 79(1):128–161. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdr017

Bissonnette L, Wilson K, Bell S, Shah TI (2012) Neighbourhoods and potential access to health care: the role of spatial and aspatial factors. Health Place 18(4):841–853. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.03.007

Brueckner JK, Rosenthal SS (2009) Gentrification and neighborhood housing cycles: will America’s future downtowns be rich? Rev Econ Stat 91(4):725–743. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest.91.4.725

Carpiano RM (2007) Neighborhood social capital and adult health: an empirical test of a Bourdieu-based model. Health Place 13(3):639–655. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2006.09.001

Cheshire PC, Nathan M, Overman HG (2014) Urban economics and urban policy. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

Chetty R, Hendren N (2018) The impacts of neighborhoods on intergenerational mobility I: childhood exposure effects. Q J Econ 133(3):1107–1162. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjy007

Chetty R, Hendren N, Katz LF (2016) The effects of exposure to better neighborhoods on children: new evidence from the moving to opportunity experiment. Am Econ Rev 106(4):855–902. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20150572

Damm AP (2014) Neighborhood quality and labor market outcomes: evidence from quasi-random neighborhood assignment of immigrants. J Urban Econ 79:139–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2013.08.004

Damm AP, Dustmann C (2014) Does growing up in a high crime neighborhood affect youth criminal behavior? Am Econ Rev 104(6):1806–1832. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.104.6.1806

Deryugina T, Molitor D (2020) Does when you die depend on where you live? Evidence from Hurricane Katrina. Am Econ Rev 110(11):3602–3633. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20181026

Edin PA, Fredriksson P, Åslund O (2003) Ethnic enclaves and the economic success of immigrants—evidence from a natural experiment. Q J Econ 118(1):329–357. https://doi.org/10.1162/00335530360535225

Eisenberg D, Golberstein E, Whitlock JL, Downs MF (2013) Social contagion of mental health: evidence from college roommates. Health Econ 22(8):965–986. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.2873

Exline JJ, Lobel M (1997) Views of the self and affiliation choices: a social comparison perspective. Basic Appl Soc Psychol 19(2):243–259. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324834basp1902_6

Grossman D, Khalil U (2019) Neighborhood networks and program participation. J Health Econ 70:102257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2019.102257

Hatfield E, Cacioppo JT, Rapson RL (1993) Emotional contagion. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Hjorth F, Dinesen PT, Sønderskov KM (2016) The content and correlates of subjective local contexts. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317618136_The_Content_and_Correlates_of_Subjective_Local_Contexts . Accessed 30 May 2018

Iversen AØ, Hansen ZJ, Hansen MF, Stephensen P, (2019) Udsatte boligområder i Danmark: En historisk analyse af socioøkonomisk segregering, flyttemønstre, indkomstforløb og effekt af bosætning i udsatte boligområder. Dream. https://dreamgruppen.dk/publikationer/2019/juni/udsatte-boligomraader-i-danmark/. Accessed 15 Oct 2021

Jacob BA (2004) Public Housing, housing vouchers, and student achievement: evidence from public housing demolitions in Chicago. Am Econ Rev 94(1):233–258. https://doi.org/10.2307/3592777

Jacob BA, Ludwig J, Miller DL (2013) The effects of housing and neighborhood conditions on child mortality. J Health Econ 32(1):195–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2012.10.008

Jones-Rounds ML, Evans GW, Braubach M (2014) The interactive effects of housing and neighbourhood quality on psychological well-being. J Epidemiol Community Health 68(2):171–175. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2013-202431

Katz LF, Kling JR, Liebman JB (2001) Moving to opportunity in Boston: early results of a randomized mobility experiment. Q J Econ 116(2):607–654. https://doi.org/10.1162/00335530151144113

Kauppinen TM (2007) Neighborhood effects in a European city: secondary education of young people in Helsinki. Soc Sci Res 36(1):421–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2006.04.003

Kling JR, Liebman JB, Katz LF (2007) Experimental Analysis of Neighborhood Effects. Econometrica 75(1):83–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0262.2007.00733.x

Leuven E, Sianesi B (2003) PSMATCH2: Stata module to perform full Mahalanobis and propensity score matching, common support graphing, and covariate imbalance testing. Boston College Department of Economics. https://ideas.repec.org/r/boc/bocode/s432001.html (version February 2018)

Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J (2003) Moving to opportunity: an experimental study of neighborhood effects on mental health. Am J Public Health 93(9):1576–1582. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.93.9.1576

Ludwig J, Duncan GJ, Hirschfield P (2001) Urban poverty and juvenile crime: evidence from a randomized housing-mobility experiment. Q J Econ 116:655–679. https://doi.org/10.1162/00335530151144122

Ludwig J, Duncan GJ, Gennetian LA, Katz LF, Kessler RC, Kling JR, Sanbonmatsu L (2013) Long-term neighborhood effects on low-income families: evidence from moving to opportunity. Am Econ Rev 103(3):226–231. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.103.3.226

Manski C (1993) Identification of endogenous social effects—the reflection problem. Rev Econ Stud 60(3):531–542. https://doi.org/10.2307/2298123

Musterd S, Anderson R (2006) Employment, social mobility and neighbourhood effects: the case of Sweden. Int J Urban Reg Res 30(1):120–140. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2006.00640.x

OECD (2016) Mental health and work—OECD. http://www.oecd.org/employment/mental-health-and-work.htm Accessed June 26, 2017

Oreopoulos P (2003) The long-run consequences of living in a poor neighborhood. Q J Econ 118(4):1533–1575

Pedersen KM (2003) Pricing and reimbursement of drugs in Denmark. Eur J Health Econom 4(1):60–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-003-0165-6

Popkin SJ, Harris LE, & K. Cunningham M (2002) Families in transition: a qualitative analysis of the MTO experience. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Office of Policy Development and Research. https://www.huduser.gov/portal//Publications/pdf/mtoqualf.pdf

Rotger GP, Galster GC (2019) Neighborhood peer effects on youth crime: natural experimental evidence. J Econ Geogr 19(3):655–676. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lby053

Sanbonmatsu L, Ludwig J, Katz LF, Gennetian LA, Duncan GJ, Kessler RC, Adam E, McDade TW, Lindau ST (2011) Moving to opportunity for fair housing demonstration program—final impacts evaluation. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Office of Policy Development & Research. https://www.huduser.gov/portal/publications/pdf/MTOFHD_fullreport_v2.pdf

Scanlon K, Vestergaard H (2007) The solution or part of the problem? Social housing in transition: the Danish case. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/48909866_The_solution_or_part_of_the_problem_Social_housing_in_transition_the_Danish_case. Accessed June 14, 2019

Steel Z, Marnane C, Iranpour C, Chey T, Jackson JW, Patel V, Silove D (2014) The global prevalence of common mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis 1980–2013. Int J Epidemiol 43(2):476–493. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyu038

Topa G, Zenou Y (2015) Neighborhood and Network Effects. In: Duranton GJ, Henderson V, Strange WC (ed) Handbook of regional and urban economics, Volume 5. Elsevier, pp 561–624 https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-59517-1.00009-X

Truong KD, Ma S (2006) A systematic review of relations between neighborhoods and mental health. J Ment Health Policy Econ 9(3):137–154

Weatherall CD, Boje-Kovacs B, Egsgaard-Pedersen A (2016) Et historisk tilbageblik på de særligt udsatte boligområder udpeget i 2014. Kraks Fond Institute for Urban Economic Research. https://build.dk/Pages/Et-historisk-tilbageblik-paa-de-saerligt-udsatte-boligomraader-udpeget-i-2014.aspx

Wodtke GT, Harding DJ, Elwert F (2011) Neighborhood effects in temporal perspective: the impact of long-term exposure to concentrated disadvantage on high school graduation. Am Sociol Rev. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122411420816

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank John Cawley, Paul Cheshire, Tom Crossley, Bo Honoré, Robert Kaestner, Michelle McIsaac, Ismir Mulalic, Henry Overman, Lorenzo Rocco, William Strange, Joshua Graff Zivin, editor Alfonso Flores-Lagunes, and two anonymous referees for their invaluable comments. We are thankful to participants in the following seminars and conferences: Cornell University’s Policy Analysis and Management seminar series, the 6th biennial conference of the American Society of Health Economists (ASHEcon), the Population Association of America (PAA) 2016, the 7th European meeting of the Urban Economics Association, the 31st Annual Conference of the European Society for Population Economics (ESPE), the 29th European Association of Labour Economics (EALE), VIVE–The Danish Centre of Social Science’s seminar, and the University of Southern California’s Workshop on Health Economics.

Funding

Partial financial support was received from Kraks Fond.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Bence Boje-Kovacs, Jane Greve and Cecilie D. Weatherall. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Jane Greve, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Data availability

The results in the paper are based on Danish administrative registry data. Unfortunately, we are not able to make these data publicly available. However, anyone can apply for data from Statistics Denmark. Foreign researchers can get access to data through an affiliation to a Danish authorized research environment. See also http://www.dst.dk/en/TilSalg/Forskningsservice. However, we are happy to guide other researchers in how to get access to data..

Code availability

We are happy to guide other researchers in how to get access to post documentation for data and the STATA programs used for this project.

Additional information

Responsible Editor: Alfonso Flores-Lagunes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Boje-Kovacs, B., Greve, J. & Weatherall, C.D. Neighborhoods and mental health—evidence from a natural experiment in the public social housing sector. J Popul Econ 36, 911–934 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-022-00922-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-022-00922-0

Keywords

- Economically deprived neighborhood

- Mental health

- Psychiatric medications

- Quasi-random assignment

- Public social housing

- Neighborhood effects