Abstract

We develop a quantitative model that is consistent with three principal building blocks of Unified Growth Theory: the break-out from economic stagnation, the build-up to the Industrial Revolution, and the onset of the fertility transition. Our analysis suggests that England’s escape from the Malthusian trap was triggered by the demographic catastrophes in the aftermath of the Black Death; household investment in children ultimately raised wages despite an increasing population; and rising human capital, combined with the increasing elasticity of substitution between child quantity and quality, reduced target family size and contributed to the fertility transition.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

We develop a unified growth (UG) model (Galor and Weil 2000; Galor and Moav 2002; Galor 2011) that closely fits a wide range of data for the English economy. In addition to explaining the break-out from the Malthusian trap, the model provides an explanation for the fertility transition and the magnitudes of the various contributions to this change. Human capital accumulation is the endogenous key driver of these transitions.Footnote 1

Two fundamental mechanisms determine this accumulation. First, negative population growth (particularly that triggered by the Black Death) selects for the removal the portion of the population whose preferences render them “less fit.” Second, major mortality events both raise surviving child costs and eliminate agents with lower willingness to choose smaller families with high child quality.Footnote 2

We show that the data imply an increasing trade-off between child quantity and quality, with the elasticity of substitution between quantity and quality rising as extreme mortality impacts. As this elasticity increases, the Malthusian demand for number of children responds less to higher wages, and the negative effect of human capital growth on the demand for children becomes stronger. These effects are conducive to economic growth because they increasingly constrain population expansion and enhance human capital formation.

Generation-specific mortality rates in our model reflect how life phases are affected differently; in particular, child death rates are higher than those of younger adults. Our model predicts that a fall in child mortality boosts target numbers of children (simply due to higher survival rates) but, in contrast to adult mortality, has no impact on investment in child “quality.”

The model offers three explanations required by UG that are consistent with the data. The first is that escape from the Malthusian trap in England was triggered by the demographic catastrophes of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.Footnote 3 After these great mortality shocks, contrary to expectations, interest rates and skill premia did not return to their previous levels despite subsequent population growth and increasing land scarcity (Van Zanden 2009, p. 162). In our model, the economy attains new, non-Malthusian equilibria, as lower mortality induces more investment in children and young people, as well as greater savings. Contributors to these equilibria are Malthus’ preventive checks: higher age among females in their first marriage, and female childlessness (Hajnal 1965).

The second explanation is that, in line with Malthus’ scheme, the long-term increasing productivity from human capital accumulation raised the demand for children, boosting the population. Unlike Malthus’s model, however, here, driven by household choice, productivity and accumulation eventually offset diminishing returns from population growth, and real wages begin to rise—just as they did in the Industrial Revolution. We show that, for England, an economic growth process was in place for a long period before the effect on average living standards became strongly apparent.Footnote 4

The third explanation is that, after the Industrial Revolution, the economy experienced a fertility transition because generalized child costs rose strongly. Both were propelled by human capital–driven technical progress rooted in family decisions and the rising elasticity of substitution between child costs and child quality. The demand for children increases with wage growth but by less as the elasticity of substitution rises. The generalized cost of child quality does not rise as much as that of child quantity because the supply of human capital expands with falling adult mortality. The shift in relative cost (of quantity against quality) lowers target family size. The rise in child cost is principally due to the increasing wage and the spread of family-financed schooling, which lowers both target family size and crude birth rate (CBR). Greater schooling implies falling child labor opportunities, another contributor to the reversal of intergenerational transfers.Footnote 5 Female literacy and the male–female wage premium play a smaller role in the decline of both CBR and net family size.

Econometric analyses (Crafts 1984; Tzannatos and Symons 1989) present exogenous changes in generalized English child costs and quality as transition explanations without longer period ambitions. Their identification is weaker than in our model.Footnote 6 We explicitly derive these generalized costs and explain their movements.

Unified growth theories (UGTs) have modeled fertility transitions as consequences of either technological progress that alters the quality/education-fertility trade-off or mortality decline (see Galor (2012) for a survey and Doepke (2005) for a model driven by mortality decline). In the present paper, both mechanisms play a part. In our model, technological change driven by human capital accumulation raises child costs. Ultimately, both these costs and human capital accumulation reduce fertility. This resembles the process discussed by Galor and Weil (2000); however, unlike them, we do not assign a positive role to population growth in technological progress because Crafts and Mills (2009), who studied the English population specifically, found no evidence for it. An alternative is to model technological change with two sectors, as done by Dutta et al. (2018). Their technological advances have different effects depending on the sector in which they primarily occur; agricultural advances boost population, whereas improvements in the non-agricultural sector enhance per capita incomes. Technological change alters relative prices and thus could make food more expensive, which would mean a higher cost of raising children. Strulik and Weisdorf (2008) hypothesized that such a price change triggered the fewer children of the English fertility transition—a hypothesis that we test in the present paper.

The paper’s theoretical contribution is to show how key time-varying parameters can explain very long-term economic growth. This is achieved by explicitly building into our model preferences endogenous to mortality shocks. In contrast to evolutionary models with two types of individuals (Galor and Moav 2002; Galor and Michalopoulos 2012), the present model postulates a distribution of types. Our model also differs from others in its evolutionary path—a continuous spectrum of steady states, not transitional dynamics. A merit of this approach is that it allows for greater flexibility in modeling and fitting the data.Footnote 7 To simulate the effects of the many processes identified in the historical literature on the English economy, the present model includes a specific auxiliary component and a structural component, providing generalizable knowledge of growth in a unified fashion.

Like Bar and Leukhina (2010), we postulate that, in England, the reduction in adult mortality improved knowledge transmission and thus became a force behind the ultimate rise in output per capita. The geographical march of the fourteenth-century plague shows that the resulting extreme mortality shocks were exogenous to the English economy. We note that the intensity and frequency of these mortality shocks diminished with the success of Western European quarantine regulations from the early eighteenth century (Chesnais 1992, p. 141). Such a decline in mortality would be exogenous to the English economy, even though it may have been endogenous to Western Europe as a whole.

In UG models, mortality is often assumed to be endogenous. Voigtländer and Voth (2013a) postulated that death rates could increase with income, due to urbanization. In de la Croix and Licandro’s (2012) model, because of a parental trade-off between their own human capital investment and the time spent rearing children, during the fertility transition, richer cohorts have additional incentives to invest in childhood development. This ensures falling mortality, along with fertility. Strulik and Weisdorf (2014) specified a two-sector UG model in which a higher survival probability causes parents to nourish their children better. This specification is the opposite of the “negative sibship size” effect described by Brezis and Ferreira (2016), which alters the Beckerian quality–quantity trade-off. The closeness of our model to the English data, facilitated by the seven overlapping generations structure, suggests that the assumption of exogenous mortality is more appropriate for England.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 sets out the components of the model, including the overlapping generations, the evolution in response to extreme mortality shocks, the household choice, Malthusian constraints, and the shock structure. Because the nonlinearities of the full model rule out closed-form solutions, the properties of a restricted version of the model are discussed, and the time paths of the generalized costs of children and child quality are then predicted in Section 3. Section 4 describes the data, and Section 5 discusses the results of both the initial calibration and the subsequent optimized estimation of the model with the implied multiple steady states. Section 5 also includes a test of the hypothesis of a rising elasticity of substitution and the time paths of generalized costs, which we compare with the model predictions. Finally, in Section 6, we simulate auxiliary regression estimates of contributions to the generalized costs to establish their relative importance in the English fertility transition.

2 The model

A theoretically meaningful and empirically measurable UG model of the interaction between population and the economy must allow for fertility choice and differential mortality chances of life stages. The traditional two-period life cycleFootnote 8 implies at least a 30-year “generation” duration, which would require transforming the annual data to 30-year averages, resulting in a considerable loss of information. On the other hand, a more refined generation structure such as a period or “Age” length of 5 years or even 1 year would result in colossal computation burden. Here, we adopt a 15-year Age to be consistent with the conventional definition of childhood; the representative agent of each generation can live up to 105 years old (seven Ages), although facing the risk of premature death. A full life includes childhood, adulthood, and elderhood, with adulthood being further divided into three Ages, in line with the different choices and constraints facing the adult.

-

Phase I, Age 0 (0~15), childhood: no decision is made, but human capital is formed then by parental choices;

-

Phase II, Ages 1–3 (16~60), adulthood:

-

Age 1 (16~30), early adulthood: working, mating and family planning;

-

Age 2 (31~45), middle adulthood or parenthood: working and childcare;

-

Age 3 (46~60), late adulthood: working;

-

-

Phase III, Ages 4–6 (61~105), elderhood: no decision is made, but care of elders is taken by the work force (either from the same family or through tithes or local taxes).

Our model consists of parameters (both time-varying and fixed), endogenous variables and exogenous variables (random shocks and those in auxiliary regressions), which are linked by three key mechanisms: (1) evolution inspired by Galor and Moav (2002), (2) individual rational optimization in the neoclassical paradigm, and (3) aggregate interactions such as Malthusian checks and marriage search-matching.

2.1 Evolution

(Sexless) agents face a risk of dying at the beginning of each age with generation-specific mortality rates m0, m1, m2, and m3.Footnote 9 All mortality rates surged during the late Middle Age due to a series of famines and plagues. This high mortality in the fourteenth century opened a new era in English history. The resulting scarcity of labor led to the breakdown of the feudal system, which cleared institutional obstacles for economic growth. The frailest childhood generation with the lowest quality were hit the most, leading to evolution of preferences over quality and quantity by extinction and heredity. For the fourteenth century, De Witte and Wood (2008) find that the Black Death was selective with respect to weakness. Almost 400 years later, in the crisis of 1727–1730, Healey (2008) shows similar selectivity; there was a close connection between poverty and mortality.

We take from Galor and Moav (2002) the insight that the distribution of preferences evolves over time; that is by inheritance and surviving major mortality events. We assume the only heterogeneity in preferences within a generation is the elasticity of substitution (s), which governs the substitutability among utility inputs. The initial probability density function of s is defined over the interval 0 and 1. s follows a uniform distribution ft(s) bounded between \( \left[{\underline{s}}_t,1\right] \), which evolves over time t.

To operationalize the evolution assumption, we assume that ordinary mortality shocks do not change the lower bound \( {\underline{s}}_t \). However, we allow that major mortality shocks (such as the Black Death) truncate the lower end of the distribution proportionately.Footnote 10 Adaptability, measured by the willingness to substitute, is the key to evolutionary survival; adaptability matters more than the preferences themselves.Footnote 11 In periods of higher mortality, the “price” of a surviving child is higher. Those that can more easily substitute child “quality” for child numbers—have a higher elasticity of substitution between numbers and quality—will be more likely to survive because they are more adaptable. They can more readily choose the lower price options. In contrast, those with inflexible preferences are less likely to survive harsh times because of their reluctance to trade quantity for quality.

We distinguish between these two types of mortality events by zero population growth, i.e., when the percentage change of population (gPt) is negative, it is counted as a major mortality event. We assume that any population shrinkage is accounted for by those with the lowest elasticity of substitution (adaptability) when major mortality events occur. Therefore, the mean elasticity of substitution evolves toward 1 in an irreversible fashion, as the lower bound \( {\underline{s}}_t \) is cut off proportionately in the following manner:

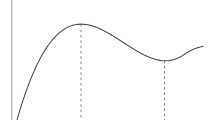

As shown in Fig. 1, the mean elasticity of substitution starts at s0 = 0.5 (the mean of the original distribution defined over 0 and 1), jumps above 0.8 during the Black Death, and finally stays stable around 0.9 before the Industrial Revolution. The implied density function of s does not change much after 1800.

2.2 Individual decisions

This component incorporates rational expectations and optimization of individual decision-making in demography and economy. Under the given (generalized) prices, the representative agent in households of each generation and producers maximize their objective functions (with n the number of surviving children per married person,Footnote 12\( {b}_t\equiv \frac{n_t}{\left(1-m{0}_t\right)\left(1-m{1}_t\right)} \) the number of crude births, q their quality relative to the parent generation, and z other consumption) subject to constraint [H]. Consumption flow zt enters the utility as a ratio rather than as an absolute level.Footnote 13 This “habit persistence” or “yearning for novelty” in material consumption has a justification from empirical psychology (Scitovsky 1976); changes in consumption, not the level, affect utility.Footnote 14

The representative agent born in periodFootnote 15t − 1 (Age 0) makes decisions in period t (Age 1), under given prices πn, πq, πz (πz is normalized to 1 as z is treated as the numeraire) with a standard CES utilityFootnote 16 (in view of the evolving substitution elasticity):

The individual’s constraint [H] defines the expected consumption flow zt as a probability-weighted average of the consumption flows with three cases. These cases are the three different optimal consumption flows (z1t, z2t, z3t) depending on whether the agent expects their life to end prematurely in Age 1, 2, or 3. The alternatives imply three possible budget constraints [Ha]–[Hc]. The consumption flows in the three states differ in the number of periods of expenditure and income as well as in whether child quantity and quality should be considered—if the agent dies before Age 2, then they would not have children.Footnote 17 The cost of each birth (πn) is averaged over all births, whether they die at birth or up to 30. In addition to childcare, the working generations also have eldercare responsibilities. The burden of caring for all the surviving old and infirm (those who are in their Ages 4–6) is shared among all the working generations (those who are in their Ages 1–3), and this burden is measured by the 60+ dependency ratio (ADR). The older generations are assumed to consume the same amount at the same price as the working generations themselves, so ADR acts like a consumption tax. Such payments might be imposed to finance the operation of the 1601 and 1834 Poor Laws, but also might be paid directly by the working family for aged and infirm dependents. In the medieval period, one fourth to one third of the tithe was theoretically meant for the poor (van Bavel and Rijpma 2016; Tierney 1959).

The production side of the economy assumes competitive output and input markets. Yt is the output per capita, \( {\hat{L}}_t \) is the ratio of working generations (defined as labor force Lt divided by population stock Pt − 1), and Ht is the average human capital per capita of the labor force. Human capital here is broadly defined to include knowledge capital, health capital, and institutional and political capital. \( \overline{F} \) is fixed natural capital such as land and natural resources proportional to land.Footnote 18 The representative production unit’s (farm’s or firm’s) problem is

Multiplying [F] by total population stock Pt − 1 on both sides yields an aggregate production function, which has constant return to scale with respect to aggregate labor force Lt, aggregate human capital HtPt − 1, and aggregate natural capital \( \overline{F} \). Without loss of generality, this last fixed quantity can be normalized to \( \overline{F}=1 \). From equation [F], the output growth rate along the balanced growth path can be derived: gY = θ2gH − (1 − θ1 − θ2)gP. Whether there is any output per capita growth (gY), or equivalently, technical progress, depends on the productivity parameters and the balance between population growth (gP) and human capital accumulation (gH).

The two optimization problems imply marginal conditions: for the household, the expected marginal rate of substitution among n, q, and z is equal to the price ratios; for the producer, the marginal product of labor is equal to the real wage (w).Footnote 19 Mortality, productivity, and price shocks ensure that all endogenous variables are stochastic. The utility function is non-stochastic, but the constraints are stochastic. Optimization implies that the objective function of household is an average of stochastic variables and the budget constraints.

2.3 Aggregate interactions

The aggregate-level variables are defined from accounting identities (≡) or from the individual-level variables associated with each other behaviorally (=).

The law of motion for the total population (Pt—total population stock at time t) is

Total deaths (Dt—death flow in period t) are the sum of premature and natural deaths. For simplicity, we assume that those who survive their Age 3 will die at four points with equal chance, i.e., at the beginning of Age 4, 5, 6 and at the end of Age 6. \( {CDR}_t\equiv \frac{D_t}{P_{t-1}} \) is the crude death rate.

Total births (Bt—birth flow in period t) depend on the population of fertile females (ages 15–45) and the total number of children (bt) determined in the household’s problem, so \( {CBR}_t\equiv \frac{B_t}{P_{t-1}} \) is the crude birth rate. To accommodate the fact that childbearing age is concentrated in the second half of Age 1 and the first half of Age 2, we divide the fertile population, (P1t + P2t), by 2.

where μt is the childlessness/celibacy rate.

[A12] is introduced later to determine the celibacy rate μt in [A3]. In the equations above, Pit denotes the generational population stock in their Age i surviving at the end of period t:

Turning to the production side, where Qt is generational human capital measuring the average human capital of the generation born in period t, the labor force and the average human capital of the labor force in period t are

In addition to the accounting identities [A1]–[A9], we describe the aggregate determination of births, deaths, marriages, and human capital under the headings preventive check, positive check, search-matching theory, and human capital accumulation.

[preventive check: Birth]

The Malthusian preventive check can be interpreted as effects through the price determination mechanisms. When mortality rates rise in the fourteenth century, the effective price of a surviving child increases, leading to a relative rise in child quality, although the absolute levels of both quantity and quality drop due to complementarity in preferences.Footnote 20 With the end of the high mortality shocks in the mid-fifteenth century, marriage age (or more precisely, the female first-time marriage age At) rises, to limit births, as implied by equation [A13] below.

We assume “generalized” pricesFootnote 21 ([A10] and [A11]) that include time costs (tn, tq) as well as monetary costs (pn, pq) incurred by these activities: consumption is the numeraire for child quantity (πn ≡ pn + w × tn) and for child quality (πq ≡ pq + w × tq). So higher wages mean higher child price and quality because of greater opportunity costs, other things equal.

The coefficients Φnt and Φqt are time varying and stochastic. With the help of exogenous historical data, we specify auxiliary regressions [R1] and [R2] in Section 5.4 below to explain the fluctuations in Φnt and Φqt (each contains a price shock \( {\epsilon}_t^{\pi n} \) and \( {\epsilon}_t^{\pi q} \)). These regressions explain the divergence between wages and generalized prices that are of paramount importance during the fertility transition when child costs rise.

[preventive check: Marriage]

The proportion μt (including both never-married and the infertile) follows an autoregression with search and matching costs (Keeley 1977; Choo and Siow 2006) depending on marriage age and wage growth:

where \( {\epsilon}_t^{\mu}\sim N\left(0,{\sigma}_{\mu}^2\right) \)

The later people marry, the higher the proportion of unmatched individuals because more people are searching for partners. Moreover, a marriage is more likely to be childless if delayed to a later age. The effect of the wage (τw) is ambiguous because the model does not explicitly distinguish male and female (Pedersen et al. (forthcoming) find a negative relation between wages and marriage rates in North Italy, for instance). According to the neo-local hypothesis, a higher wage means a greater chance of getting married and a lower μt. However, if the rise in wage is mainly due to the rise in female wage, it implies a higher opportunity cost of early marriage and a higher μt. We leave the sign to be pinned down by the data empirically.

where \( {b}_t\equiv \frac{n_t}{\left(1-m{0}_t\right)\left(1-m{1}_t\right)} \)

[A13] is a time and social convention constraint (Hajnal 1965; Voigtländer and Voth 2013b). The age of first-time marriage (At) follows an autoregression and is negatively affected by the total births per married woman bt (rather than target live births nt). When bt rises (either due to a higher demand for number of children or due to a higher child mortality rate), At drops because the highest average mother’s age at the final birth is assumed to be fixed (at 45 years old). The target number of surviving children is defined as children surviving up to 30 years old for the reason of eldercare. This is why both m0 and m1 are considered.

[positive check: Death]

Mortality rates are specific to each generation or Age. The improvement of life expectancy in the last two centuries is mainly attributed proximately to a secular decline in m0 (0~15). The substantial changes in m1~m3 were from much lower levels. Greater life expectancy can raise the returns to investment in human capital because there is a longer period over which the benefits accrue. Eventually, accumulation can trigger an acceleration of technical progress (Boucekkine et al. 2003; Lagerlof 2003; Cervellati and Sunde 2005).

[human capital accumulation]

We adopt a broad conception of human capital, following OECD (2001). It includes advances in useful knowledge, from schooling, from successful technological innovations, from parenting, and from many other sources. Schooling itself corresponded less to investment in human capital than to signaling for much of the period. For most centuries, secondary schooling (by grammar schools) was dominated by the teaching of Latin grammar (e.g., Curtis 1961, pp. 24, 88–9, 113; Orme 2006, ch. 3) mainly intended to prepare the student for an ecclesiastical career. Samuel Pepys—diarist, Royal Navy reformer, and President of the Royal Society in 1684—attended St Paul’s School and graduated from Magdalen College Cambridge in 1654 yet was obliged to learn multiplication tables at age 29 in 1662.Footnote 22 We therefore estimate human capital accumulation from the model, rather than using schooling-based measures such as that in Madsen and Murtin (2017).Footnote 23

“Generational human capital” Qt is determined in period t and takes effect in period t + 1. The parents’ influence is Qt − 2 qt − 1: the target quality of children formed by “family education”.Footnote 24 There is also a “nonfamily education” effect from the average human capital of the existing labor force Ht. Formal schooling and apprentice training are still “family education” if fully financed, and the returns are fully captured, by the family. “Nonfamily” education is an externality or spill-over effect such as caused by tax-financed education and urbanization (Lucas 1988). The contribution weight of nonfamily education (an externality) is ε, and there is a human capital productivity shock \( {\epsilon}_t^Q \) to capture the efficiency of knowledge transmission.

where \( {\epsilon}_t^Q\sim N\left(0,{\sigma}_Q^2\right) \)

In the special case where there is no external effect of nonfamily education, ε = 0. [A14] is then a simple quadratic function of the human capital growth rate: \( q={\hat{H}}^2 \). Human capital growth comes only from family education in quadratic form because there are two “generations” between the parents and their children. As the externality from nonfamily education increases, perhaps due to an expanding role of the state, child quality increases (for given past human capital), because by assumption ε < 1, to ensure constant returns to scale in [A14].

2.4 Stationarization and steady states

The system is non-stationary because of growth in human capital and population. However, standard numerical methods for solving this dynamic equation system require stationarity. nt, qt, At, μt are stationary by definition; for them, no change is necessary. The non-stationary endogenous variables can be categorized into three groups in terms of their balanced growth path rates, or of their deflators. Where a hat “^” indicates a stationarized variable:

The model is solved by a perturbation method from the DSGE literature, involving log-linearization of the original nonlinear equations around the steady state (Blanchard and Kahn 1980).Footnote 25 We first obtain the steady state for each period separately and then add on the complementary functions to capture the deviation from the steady state.

We only focus on steady states in the neighborhood of the observations, so the uniqueness of the steady state in each period is guaranteed. This also marks a difference between our model and that of Galor and Weil (2000). The latter has two equilibria (two solutions) from a single parameterization, with one being a Malthusian regime and the other a modern growth regime.Footnote 26 In contrast, our model explains history assuming a unique steady state in each (15-year) period, and a series of evolving processes lead to multiple steady states over time.

To obtain these time-varying steady states, we make use of the moving averages of two key observables after stationarization, population growth (\( \hat{P} \)) and wage growth (\( \hat{W} \)), to recursively calculate the steady states of other endogenous variables. We have 25 equations for the 25 endogenous variables discussed. If two of them (\( \hat{P},\hat{W} \)) are already known, two extra degrees of freedom remain. We have two unknown time-varying parameters, i.e., Φnt, Φqt, enabling the identification condition to be met—25 equations for 25 unknowns.

2.5 Shock structure

Random shocks make the model stochastic. Without the random shocks, the model becomes a deterministic model with perfect foresight and would not be consistent with the assumption of rational expectation. Shocks also enable the model to be estimated, as they do in regression analysis.Footnote 27

If we wish to use all the observables to estimate the model (there are six in total—P, W, B, D, A, and μ), in principle we need six shocks. However, P and W are the most reliable data and they span the whole sample period. To minimize the distortion due to data uncertainty, we only use P and W as observables, so only two shocks are needed. The two most important—price shocks to πn and πq equations (\( {\epsilon}_t^{\pi n} \), \( {\epsilon}_t^{\pi q} \))—are utilized.

Lee (1993) maintains that exogenous shocks were principally responsible for the approximately 250-year European demographic cycle. The 1348 Black Death shock clearly originated elsewhere than England and wreaked simultaneous havoc elsewhere as well. Exogenous Western European quarantine regulations from the early eighteenth century subsequently reduced the impact of plague in England (Chesnais 1992, p. 141). A substantial part of the nineteenth-century decline in mortality was due to advances in public health, but these benefits took decades to be fully experienced (Szreter 1988; Colgrove 2002).

The effects of epidemic diseases such as bubonic plague, typhus, and smallpox are included in the mortality variable. Weather-induced shocks to agricultural productivity cause changes in prices and quantities and affect wages in Voigtländer and Voth’s (2006) model. Runs of poor harvests (such as the Great European Famine of 1315–1317) and livestock disease constitute a negative productivity shock. In the model, these mortality and productivity shocks are incorporated in the two generalized price shocks (ϵπn and ϵπq) in Φnt and Φqt.

After it has been solved, the whole system of Section 1 is estimated at the same time, to minimize the distance between the predicted and observed data.

3 Model properties

Unlike many Unified Growth calibrated models, ours has a CES utility function—to permit the evolution of s ≤ 1; the approach precludes closed-form solutions. Nonetheless, it is helpful for understanding the properties of the model at first to restrict the elasticity of substitution to one (s = 1) in the utility function (by the time of the fertility transition, we have shown in Fig. 1 that s has evolved quite close to 1). Assuming a unit elasticity allows the derivation of several quasi-reduced form relations by combining subsets of the equilibrium conditions (detailed derivations are in Appendix I at https://ideas.repec.org/p/cdf/wpaper/2020-13.html). These relations are then employed to explain the key events of UG.

The model’s structural equations are condensed into the following semi-solved equations in the limiting case of s = 1:

Equations [X1] and [X2] are obtained by combining the price determination equations with the wage determination equation. They also remind about the definition of generalized prices (πnt, πqt) where (tn, tq) are child time costs and (pn, pq) are child monetary costs. Equations [X3] and [X4] are obtained by combining marginal conditions with respect to n and q in the production function with the budget constraints. Equation [X5] links adult mortality and human capital to the supply of child quality. Equilibrium n and q determine respectively the future labor force (L) and human capital (H), the two vital inputs of the production function [F]. Economic growth therefore alters when n and q, the two underlying variables, change along the evolving steady-state path.

For brevity, we define the effective price of children to include the effect of child mortality rates in equation 3:

and the expected lifetime wealth along the balanced growth path:

where technological change \( \hat{X}\equiv {\hat{H}}_t^{\theta_2}{\hat{P}}_{t-1}^{\theta_1+{\theta}_2-1} \) is defined in Subsection 1.4.

When m0 and m1 fall, effective child price declines, raising the demand for n [X3]. Lower child mortality raises target family size n but reduces the birth rate necessary to achieve that target, so b does not change (when s = 1). When s < 1, b rises with n.

Wages in the numerator and denominator of [X3] cancel out; they have no effect on the demand for children when s = 1. With s < 1, as it was throughout, the income effect of a wage increase dominated the substitution effect—demand for children increased with wage growth but by less as the elasticity of substitution rose. So, the population effect of wage increases mattered more in the fourteenth century than in the eighteenth century.

The sign of the partial derivative of child demand with respect to human capital is negative so long as m2 is less than 50%, which must be true outside the fourteenth century. The rising elasticity of substitution means the effect of human capital reducing child demand increases with economic development. This human capital effect is one contributor to the fertility transition. As m2 falls, there is a greater effect in absolute value on the demand for children from a rise in human capital.

The quasi-reduced form equations can show the principal elements of the model’s explanations for the three key events of Unified Growth. The first is the beginning of the break-out from a Malthusian equilibrium.

The mortality shocks of the fourteenth century almost halved the population, boosting the generalized prices of children and of their quality, πn and πq (see [X1] and [X2], lower P), and raising wages. In the long term, the higher πn shifts the quality qD curve to the right ([X4] point 2 in Fig. 2). It encourages families to reduce the number of children (n is lower) and to substitute investment in their quality. q is higher, triggering eventual faster human capital accumulation. In the short run, increase in adult mortalities shifts the qS to the left raising πq to point 1, before mortality rates fall back. Higher child mortality reinforces the contraction of n and the fall in population, with an inward shift in nD (not shown).

Faster human capital accumulation (moving leftwards along the left horizontal axis of Fig. 3) precedes the second event to be explained, the Industrial Revolution. m0, child mortality declines (from, say, 1700), moving nD rightwards (increases demand for children, see [X3]). The consequent rise in n generates population growth which has a negative impact on wages, see [X1], tending to reduce generalized prices (shifts the H–π curves inwards). At the same time, lower adult mortality moves qS to the right reducing πq, ultimately increasing H and offsetting the downward pressure on wages. A lower πn shifts qD down (the cross-elasticity in [X4]) reducing the growth in quality that would otherwise have occurred, altering demand toward child numbers.

The third event, the fertility transition, follows the Industrial Revolution. Human capital continues to grow, and technology raises child cost (pn), pushing Φn upwards at the same time (see [X2]). The two effects increase generalized child price πn and lower n; they encourage fewer children. Not shown in Fig. 4, the negative effect of human capital H on nD is given by the left shift of the nD curve. The higher generalized child price encourages substitution away from child numbers to quality, and qD shifts to the right because of the cross-elasticity in [X4]. This effect is reinforced by lower adult mortality improving the supply of child quality.

4 Data

In the selection and construction of the model data, our representative agent is assumed to earn the average wage income; that is, a weighted average of male and female incomes (where female income is average working hours times average wage rate). This average is constructed from the male daily wage rate mainly from Clark (2005, 2007), summarized in Clark (2018), which has the advantage of covering the entire period of the UG model, 1209–2016, in a reasonably consistent fashion.Footnote 28 It is supplemented with the female wages from Humphries and Weisdorf (2015) (using weights derived from Horrell and Humphries (1995) and Levi (1867), see Appendix II at https://ideas.repec.org/p/cdf/wpaper/2020-13.html). Daily wages are a good measure of the marginal product of labor for they include fewer non-pecuniary payments (such as board) than annual contracts. On the arbitrage principle (Clark and van der Werf 1998), the daily wage rate should be equivalized with the payments to annually contracted workers.

For simplicity, the labor supply in the model is assumed perfectly inelastic at the internal margin, even though the extraordinary rises of wages in the post–Black Death economy must have been accompanied by a reduction of hours worked (Hatcher 2011) and, for instance, Voth (1998) shows an increase in nineteenth-century annual working hours with the decline of “Saint Monday.” We expect that in practice, reductions or increases in work were chosen according to the value of leisure at the margin. A higher wage rate allows more leisure for the same income so is an increase in well-being, even if real money income does not rise.Footnote 29 For this reason, we do not use the Broadberry et al. (2015) national income per capita measures. And to avoid greater complexity, we make no attempt to model changes in income distribution.

We use Broadberry et al. (2015), in Bank of England, A Millennium of Macroeconomic DataFootnote 30 (Table A2), for annual data for England’s population 1086–1870 and the Bank’s Table A18 for English population from official Census sources from 1841 to 2016. Wrigley et al.’s (1997) demographic data from family reconstitution and generalized inverse projection, from when Parish Registers were first kept, is the basis of Broadberry et al.’s data for 1541–1870. The Broadberry data show that population fell by more than a half in the crisis of the fourteenth century, beginning to recover from 1450. Population returned to the pre–Black Death peak by the early seventeenth century, when growth ceased and even declined temporarily. By then, real wages were more than 20% higher than in the half century before the Great European Famine of 1315–1317. A new higher wage floor seemed to have been reached in the 50 years after 1600, consistent with the “high wage economy” (Allen 2015) originating in the changes of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

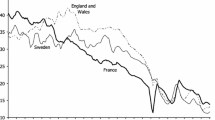

Population growth accelerated in the eighteenth century without reducing real wages and in the first half of the nineteenth century wages began to rise along with population. Population slowed with the late-nineteenth-century fertility transition. Crude birth rate (CBR) fell in England and Wales from the 35 births per 1000 population in 1871 to 24.3 in 1911 (and to a low of 14.4 in 1933) (Mitchell 1962, pp. 29–30). Proximate causes of this decline were the rise in female first marriage age from 25.13 in 1871 to 26.25 in 1911 and rising childlessness (or celibacy): the proportion of married women aged 15–45 fell from about 50 to 48% (calculated from Mitchell 1962).Footnote 31

In our model, the ultimate causes of the fertility transition are the changes in generalized price of children, πn, which are driven by processes reflecting the “natural” path of technical progress. Such processes could include changes in relative (to male) female wages. In industry, this ratio hardly increased for textiles between 1886 and 1906 (Bowley 1937, table 10, p. 50), but there is some evidence that female domestic service wage rates rose relative to manufacturing (Layton 1908), as did those of female post office clerical workers (Routh 1954).

Increases in the direct cost of childbearing (pn in the model) include the costs of schooling as well as accommodation, care, food, and clothing. When child labor was widespread, the intergenerational transfer may have gone from children to parents. From 1833, legislation was passed (but not always enforced) about the age at which children could work (at 10 they could begin, with half-time schooling from 10 to 14). As legislation and practice reduced child labor, the transfer increasingly went the other way. Crafts (1984) finds that rising relative child costs were a crucial contributor to declining English fertility. However, he does not directly consider schooling, instead employing price indices to measure aspects of child costs.

A common way of measuring English schooling costs (e.g., Tzannatos and Symons 1989; Galor 2005) is to use only attendance at inspected schools, i.e., those in receipt of some government funding. This very much underestimates schooling for most of the nineteenth century; Lindert’s (2004) estimates of schooling by decadeFootnote 32 shows in 1850 almost eight times the enrollments in total, as attendance in inspected schools. The 1870 Forster Act allowed the creation of School Boards empowered to create byelaws to compel attendance if they chose. From the 1880 Act onwards, school attendance was compulsory for 5–10-year-olds and the leaving age was raised to 11 in 1893 (Curtis 1961). The already small proportion of the workforce under 15 declined accordingly, from 6.9% in 1851 to 6.8% in 1861, 6.2% in 1871, and 4.5% in 1881, suggestive of an inverse association between school attendance and work (calculated from Booth 1886). Most public elementary schools were free from 1891, but this was after the fertility decline began. In 1899, the school leaving age was raised to 12.

Information, ideology, and ideological change could play a role in fertility decline, creating a willingness to adopt more effective contraception (Crafts 1984; Bhattacharya and Chakraborty 2017). Ostry and Frank (2010) and Guinnane (2011) dismiss innovations in contraception as drivers of fertility decline because they were insufficiently widespread or cheap enough to have a substantial effect.

However, as CBR decline began, the 1877 Bradlaugh-Besant obscenity trial publicized the idea of birth control. As opposed to a previous average circulation of about 700 copies a year of the text at issue, Knowlton’s Fruits of PhilosophyFootnote 33 (1832), between March and June 1877, 125,000 copies were sold (Banks and Banks 1954). The impact was greater than measured by increased sales, for newspaper reports of the trial reached people who would never have bought a “dubious” pamphlet.

A core problem of the present paper is to show quantitatively the impact of these possible contributors to the fall in CBR and in target family size and to explain how they fit in to UGT.

5 Results

The model is initially calibrated from 2SLS estimates of a subset of model equations wherever data are available. Because of the evolutionary path of st, the steady state of the model in each period is solved with these calibrated parameters. The steady state in each period varies also because of exogenous changes in age-specific mortality rates. Next, a global optimization algorithm is applied to search the parameter space for the best set of values to minimize the squared gap between the model predictions and data observations. The parameters are those in Table 1, and the sequences {Φnt, Φqt}, t = 1100, 1115, …, 2000. The matched data are population growth and real wage growth (top row of Fig. 5). The remaining four panels of Fig. 5 are model predictions. The estimated model is then simulated under different settings to identify the contributions of model mechanisms to the demographic transition and long-run economic growth in England.

Comparison of key variables between the model and the data. The data sources can be found in Appendix II at https://ideas.repec.org/p/cdf/wpaper/2020-13.html. The black lines are the evolving steady states and the red lines are the data

5.1 Empirical performance

In Table 1, the calibration column includes the parameter values either from 2SLS estimates (the first seven) or from guestimates (the rest), while the estimation column includes the final estimates starting from all these initial values. The first three parameters are for the first-time marriage age (A) equation [A13]. The negative coefficient indicates by how much a fall in target births raises A. The next four coefficients are for the childlessness μ equation [A12]. The second parameter τμ indicates that the final estimate for childlessness is negatively autocorrelated, and the third τA shows that a higher marriage age raises the childlessness rate proportionately. The fourth coefficient τw indicates that faster wage growth boosts childlessness. The human capital elasticity of output is high (θ2) compared to unskilled labor (θ1), leaving 0.403 for fixed inputs such as land. ε of 0.394 indicates that human capital spillovers accounted for two thirds as much as privately born investment in human capital [A14].

In Fig. 5, the evolving steady states of population and earnings growth capture the broad data movements over 800 years. When their indices exceed 1, there is growth, which for real wages begins after 1800.Footnote 34 The population decline during the fourteenth century is not captured because steady state population growth cannot be negative.

Using population and earnings as the inputs to the model, we recursively derive the other endogenous variables. The remaining four panels can be thought of as a form of “out-of-sample” predictions of these endogenous variables. The fall in the CBR in the nineteenth century is captured quite well, as is the decline in CDR.Footnote 35 Predicted and actual marriage age and childless rate both rise in the period of fertility decline. As endogenous variables, their effects on CBR, outlined above, are taken into account when the responses to exogenous variables are considered.

The discrepancy between the model predictions and the collapse of first-time marriage age in the late fifteenth century may reflect problems with the baseline data (here a small sample of Inquisition Post-mortems, Russell 1948) rather than shortcomings of the model. That is, the simulated series here may be a better guide to history than the available “data,” similarly with the childless rate which apparently shoots up in the seventeenth century and collapses in the eighteenth century. A jump in clandestine marriage (and therefore overestimation of childlessness) may have been a contributor to this statistical oddity (Schofield 1985).

In Fig. 5, the gray bands are 90% CIs.Footnote 36 The data mainly lie within these intervals generated by the model simulations. Hence, the model seems likely to be the data-generating process of the observed data.

5.2 The evolution of preferences

The impact of the Black Death and other crises of the fourteenth century is hypothesized to eliminate agents with lower willingness to choose smaller families with high child quality when child price rises. We can test whether the demographic shocks of that period and later were responsible for the ultimate break-out from the Malthusian steady state. by simulating the model without a rise in the elasticity of substitution between child quality and child numbers from the fourteenth century.

Figure 6 supports the hypothesis. It shows that with an unchanging initial elasticity of substitution (of 0.5), earnings do not recover the fifteenth century peak until almost the end of the twentieth century. By contrast, with an unchanging unit elasticity of substitution, earnings rise far too strongly to match the data or our model predictions.

5.3 Explaining the path of generalized prices

The ratio between πn and πq is a vital mechanism for economic and demographic growth, especially in the three key phases discussed here. The time paths of πn and πq (Fig. 7) are derived from the structural model equations and the observed variables population growth \( \hat{P} \), wage growth \( \hat{W} \), and mortality rates m. As predicted in Section 3, child “price” rises in the high mortality fourteenth century, increasing the demand for child quality and thereby bidding up the price of quality. Moreover, the human capital expansion only weakly increases the supply of child quality, ensuring the price of quality continues rising when child price turns down.

From the mid-sixteenth century to the beginning of the eighteenth century, child price rises again (and slows down population growth). Thereafter, until the beginning of the fertility transition of the later nineteenth century, the “price” declines, encouraging population expansion. Indicative of the growth of human capital, πq dropped remarkably from 1550 onwards, driving the rise in the πn/πq ratio and the slow acceleration of economic growth of the Industrial Revolution.

After 1850, human capital, driving technological progress and wages, raised the generalized child price πn strongly, reducing the (crude) birth rate and target family size. The other human capital effect, contracting the demand for children, was not completely offset by falling infant mortality and rising wages [X4]. The rise in child price reflects the rise in celibacy rate and the age at marriage. However, falling mortality increasing the supply of child quality seems to have prevented the quality price rising very much when demand expanded [X2].

5.4 Explaining the shocks to generalized prices

The structural model proposed is generic to all economic conditions, but countries may experience different factors driving the changes of generalized prices. To account for this specific heterogeneity, we use auxiliary regressions to capture the detail of the transition in the English case. From [A10] and [A11] of the structural model, the ratio Φnt/Φqt is equal to relative prices πnt/πqt. We propose two auxiliary regression models to explain these two time-varying parameters Φnt and Φqt.

In UGT, technological progress is exogenous in the sense that there is a hierarchy of knowledge and a fixed path (not pace) of technical advancement. Along this fixed path, there are some accompanying processes to embody the exogeneity of technological progress. To explain the changes in Φnt and Φqt, we identify the following candidate processes, which are exogenous to the structural model:

-

School enrollment (SCH), driven by increasing technological sophistication.

-

Inspected school enrollment (\( \overset{\sim }{SCH} \)), similar to SCH, but inspected school enrollment usually reflects effective and high-quality education.

-

Male–female wage premium (WP), mainly caused by structural transformation and its impact on the role of women in the service sector.

-

Female literacy (FL), perhaps mainly caused by also by structural transformation.

-

Urbanization (URB), mainly caused by rising productivity and transportation and communication technologies improvements.

-

Food price ratioFootnote 37 (FPR), mainly caused by agricultural productivity and foreign trade.

The two auxiliary regressions ([R1] and [R2]) estimate the impact of this period- and country-specific technical progress on the two shocks to \( {\hat{\pi}}_{nt} \) and \( {\hat{\pi}}_{qt} \):

Column (1) of Table 2 indicates that the strongest effect on the relative generalized child price (Φn or the ratio \( \frac{\pi_n}{w} \)) is from school attendance (SCH), confirmed by the simulations below. A higher school enrollment implies a smaller child labor income, as well as greater direct costs, so it increases the effective price of child. The male wage premium (WP) implies that higher relative female wages raise the generalized child price because of the higher opportunity cost of childcare. There is a positive (but statistically insignificant) effect of urbanization (URBFootnote 38), reflecting that higher mortality and rents, and greater opportunities of city life raise the cost and price of children.Footnote 39

If we use the full sample to estimate the lnΦq equation (column (3) of Table 2), then female literacy (FL) has an insignificant effect. However, this is mainly due to the poor quality of the data on female literacy before 1400. If we restrict our sample to 1400+ (column (4)), then the effect of FL on lnΦq is significant and negative. The ADF tests show that the auxiliary regressors in columns (1), (2), and (4) are co-integrated with the dependent variables. The exception is column (3). As argued earlier, the subsample estimates of column (4) are more credible. The sign of the estimated coefficient of FPR confirms the hypothesis of Malthus and Strulik and Weisdorf (2008); more expensive food means a higher price of children and therefore fewer children (as in a demographic transition). However, English nineteenth-century food prices declined, so they contributed to a fertility increase rather than a decrease.Footnote 40

5.5 Simulations

First, we evaluate the importance of the relative prices of n and q to the fertility transition in the late nineteenth century. Setting Φn and Φq at 1850 levels is equivalent to fixing the price ratio between n and q, because wage (\( \hat{w} \)) in both cancels out according to [A10] and [A11]. In this case, a demographic transition no longer takes place and (the 15-year aggregate) CBR stays above 65% (Fig. 8). Furthermore, Fig. 8 also shows that changes in Φn are the main contributor to the transition, while the effect of Φq is insignificant.

Simulations of CBR with fixed generalized price ratios. The model predictions are based on the steady states solved under the estimated parameters. The two time-varying parameters Φn and/or Φq are then fixed at the 1850 level to simulate the consequent CBR to see the effect of prices. The CBR here are defined in line with the data, i.e., 15-year birth flow divided by the beginning-of-period population, which is higher than 15 multiplied by the annual CBR due to an expanding population base. Fixing Φqdoes not alter history significantly, as it lies within the 90% band, but fixing Φn does

To explore the detailed story behind the English fertility transition, we can fix the significant exogenous processes in the auxiliary regressions (1) and (4) in Table 2 and simulate the structural model to see how much these processes contribute to the fertility decline. If schooling was fixed at (the low) 1850 levels, Φn and therefore \( {\hat{\pi}}_n \) would have been lower according to the auxiliary regression, so the target number of children would have been much higher (Fig. 9). By contrast, fixing the food price ratio at 1850 levels has very little effect on counterfactual child numbers; the time path lies easily within the 90% band. Changes in the male–female wage premium and female literacy contribute to a higher opportunity cost of nFootnote 41. Setting all auxiliary processes to 1850 levels raises target number of children by about the same as fixing schooling, until well into the twentieth century. Actual mortality dropped so that setting all mortality to the high 1850 rates lowers the target number of children (n); a greater number of births would be necessary and therefore surviving child costs would be higher. This is what nD predicts ([X3]). Hence, the simulated n with all auxiliary processes fixed is pulled down (fewer children) when mortality is combined with all auxiliary processes.

Figure 10 shows that the simulated CBRs, under various ways of fixing auxiliary processes, does not decline substantially in the late nineteenth century. The conventional demographic transition story is that mortality falls and then births (CBR) fall with a lag. Had mortality remained at 1850 levels, along with the wage premium and schooling, crude birth rate would have risen. However, on its own, lower mortality did not contribute to the decline of CBR because the higher target family size offsets the smaller number of births necessary to achieve a target. The single factor contributing most to CBR decline was schooling/child labor. Mortality decline would have raised CBR substantially had it not been for the rise in opportunity cost of schooling (driven by technology), although the wage premium and female literacy also made a substantial contribution to the fall in the family target.

6 Conclusion

The structure of our unified growth model for England follows Galor and Moav (2002) and Galor and Michalopoulos (2012) in its evolutionary approach but differs in its greater historical specificity. The model is consistent with the technology-driven explanations of UGT supplemented by exogenous mortality.

A distinctive response to catastrophic fourteenth-century mortality sets off the process that eventually makes the break from the Malthusian state: the shift to more adaptable, family-directed accumulation of human capital. From around 1550, the price of child quality was falling, facilitating the build-up of human capital. Falling mortality and child price after 1700 promoted population growth, while human capital built up sufficiently first to prevent real wages falling, and then to allow them to rise during the Industrial Revolution.

In the next stage, the English fertility decline, generalized child price climbed strongly because technology raised child opportunity cost, and human capital growth pushed up wages. Rising human capital accumulation held the increase in child quality price below that of child numbers. One response to the child price change was an increasing proportion of women remaining unmarried and a later marriage age. We find that falling mortality had little effect on CBR and actually raised target family size. Fewer births were necessary for a given completed family size. The rising opportunity cost of children was generated by growing school attendance and the reduced opportunity for child labor. It has been common to underestimate the strength of the rise in English schooling in the early nineteenth century because it was not provided or monitored by the state. The increasing cost of greater school attendance can be interpreted both as a trigger for the substitution of quality for quantity and as a reaction to technical change that placed an increasing premium on human capital—as in Galor (2012). Without this change, target family size would have increased substantially after 1850s or 1860s.

Female literacy and the male–female wage premium also contributed to the increase in generalized child price. Malthus’ and Strulik and Weisdorf’s (2008) emphasis on food prices is appropriate for pre-industrial times but, since the relevant price ratio fell after 1850, crude birth rates would have fallen if food prices were held at 1850 levels. Rather than contributing to the fertility transition, they were a countervailing force.

Despite the complexity of the 25-equation model, it is still a simplification, not taking into account changes in labor force participation, income distribution, migration, or other spillovers from the rest of the world—with the exception of the assumed exogeneity of mortality. Inability to measure child labor means that we have been unable to distinguish between this effect on the transition and that of schooling. We can only account for changing values and information such as might have been triggered by the publicity of the Bradlaugh-Besant Trial, by the shocks to the generalized child price. Since the regression accounted for 88% of the child price variance, only a small proportion remains unexplained, available to be allocated for example to Bradlaugh-Besant publicity effects.

Fertility transitions have occurred in all high-income countries, but at different times, different speeds, and apparently at different stages of development. This model has implications for other countries, such as those placing a de facto tax on the number of children per family (as in East Asia), which boost investment in child quality and human capital. Optimal child number therefore falls, and more resources are spent on quality. Such unique national experiences in policy and cultural environment can be incorporated in auxiliary regressions to extend the generic model here.

Change history

02 February 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-021-00822-9

Notes

Following Becker (1981), child costs or prices are defined in general terms, including both the monetary and time costs of raising and educating a child (both formally and informally). There is good evidence that pre-modern couples did indeed influence their birth numbers and target their family size (Cinnirella et al. 2017) as well as trade off child quality against quantity (Klemp and Weisdorf 2019). Alternative but broadly similar trade-offs in the literature include social mobility as a trade-off for child quality (Cummins 2009), the number of children against adult human capital (De la Croix and Licandro 2012), and, in more detail, the agent’s choice of skilled or unskilled human capital against the number and quality of children (Cervellati and Sunde 2015). In this last model, net fertility declines as skilled capital accumulates because skilled workers have fewer children than unskilled. We differ from Cervellati and Sunde (2015) by not imposing their fixed cost of children, while they exclude the cross effect that higher child cost increases child quality in our model.

Voigtländer and Voth (2013a) also identify the fourteenth-century demographic shock as critical; however, theirs is not a UG model.

This is the opposite of Lagerlof (2019), who demonstrates that the absence of a growth process—a Malthusian model—could still generate a strong rise in GDP per capita for later eighteenth-century England. However, unlike us, he does not attempt in the same model to explain the fertility transition.

As schooling increased, children born between 1851 and 1878 started working later than those born during the classic Industrial Revolution period (Humphries 2012, p. 370).

Identification is problematic in their papers because, as in our model, generalized prices at the aggregate level are endogenous.

Lagerlof (2019) ingeniously constructs an annual data model, avoiding the use of overlapping generations, focusing instead on “overlapping” in the composition of labor force. No human capital accumulation is modeled whereas it is in our model.

Following Galor and Weil (2000), Lagerlof’s (2006) calibration is illustrative. This exercise simplifies life to two generations. Consequently, there is no infant mortality rate and only one mortality rate in the adult period. Each period is 20 years, so the full adult life is only 40 years. Population begins falling in generation 40 (equivalent to 1870) and stops growing in generation 45 (equivalent to 1970 because a period = 20 years) which is at odds with the data.

The ms are defined at a point in time not for a period. So m0 is infant mortality at birth and m1 is the chances of dying at 15 years old and m2 at 30 years old. We assume those who survive Age 3 have equal chances of death at the beginning of Age 4, 5, 6 and the end of Age 6. Therefore, the mortality rates at these four points during phase III are respectively 1/4, 1/3, 1/2, and 1.

Because the distribution is assumed to be uniform (for simplicity)—all values of the distribution are equally likely—the distribution shape is not changed by the mortality shock. However, the key element of the model is that the shocks change the mean of the distribution by removing the left side, those without evolutionary advantage, and this principle is not affected by the assumed distribution.

There are 2푛 surviving children per household and per mother.

This formulation is crucial for the model steady states. It is a natural extension of static Becker-type models to a dynamic context. The alternative ways of achieving dynamic steady states usually involve ensuring other variables of the preference function, typically some product of wages or human capital of children and numbers of children, grow at the same rate as consumption. Our approach permits the separability of q (child quality) from n (child numbers) which is necessary to allow our evolutionary trade-off and for the elasticity of substitution between n and q to change.

Because the other two utility inputs (n and q) are stationary, the third utility input must be also. Becker et al. (1990) instead invoke parental altruism as an alternative to including child quality in the parental utility function.

A period is named by the end of that period, e.g., period t is the interval [t − 1, t]. The time subscript of a variable indicates when it is determined, not when it takes effect, e.g., zt is the consumption determined in period t, but it affects periods t, t + 1, t + 2.

This standard CES specification here is equivalent to a probably more popular alternative with no 1/s powers on the utility shares (α, β, γ) only if s is constant. With an evolving s, the powers 1/s are necessary to ensure α, β, γ are constant utility shares (i.e., α + β + γ = 1) for all values of s.

The constraints include b rather than n because even births that die prematurely are costly.

As do Galor and Moav (2002), we assume that there are no property rights over \( \overline{F} \), so the return to \( \overline{F} \) is 0. This is equivalent to excluding the landlords from our model. Marx and Engels abhorred: “in extant society, private property has been abolished for nine-tenths of the population; it exists only because these nine-tenths have none of it.” (Lindert 1986, p. 1127).

For details, please go to the online Appendix available at https://ideas.repec.org/p/cdf/wpaper/2020-13.html.

This implies that the elasticity of substitution (s) is always smaller than 1. In a static version of the model, we proved that there is no converging solution when s > 1. That is, the complementarity always dominates substitutability in the preferences over current and future generation and over “bearing” and “caring.” The reason is that when s > 1, the substitution effect is so strong that child quantity will easily fall below 1, leading to an unsustainable population shrinkage.

Note that πzt can be normalized to 1 only if z does not cost any time for consumption, i.e., tz = 0. Mortality is not included in these generalized prices.

Diary of Samuel Pepys, Friday 4th July 1662 https://www.pepysdiary.com/diary/1662/07/04/.

The classical curriculum overstates the value of schooling for human capital. Understatements come from major omissions from the Madsen and Murtin (2017) measure; see their footnote 4 and their judgment that the lack of long continuous data makes it difficult to draw firm conclusions from the apprenticeship estimates.

q is defined as the ratio of children’s to parents’ human capital. It is therefore multiplied by the parents’ generational human capital to convert the bracketed expression to an absolute value of family-originating human capital.

Throughout the aggregation, we use the average of sum for the sum of the average, an approximation. The two are not the same because of nonlinearity, but they are equivalent when the equation system is solved by linear approximation, as ours is.

The model of Foreman-Peck and Zhou (2018) also had only two steady states.

This approach is standard in Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium analysis, for example, Smets and Wouters (2007).

Allen (2001) has an index for London and the South East, but this does not cover the regions where the industrial revolution was taking place and so is likely to understate the English average in the eighteenth century. Gilboy (1936) showed nominal wages in Lancashire doubled between 1700 and 1770 while London nominal wages only rose by one fifth. Hunt (1986) identified a similar regional change between the 1760s and 1800. For this reason, we adopt the broader coverage Clark series.

Hence, the Weisdorf (2019) measure of real income is not appropriate for our purposes.

The illegitimacy rate was low and falling.

The course of real wage during the Industrial Revolution remains controversial (Allen 2009; Feinstein 1998; Lindert and Williamson 1983), but it is not the purpose of the present paper to adjudicate between competing estimates. Rather, it is to show that the model can explain both an upturn in wages and the eventual decline in fertility.

CDR (crude death rate) depends on the overlapping generational structure of the model as well as exogenous mortality rates. The tendency for simulated CDR to be too low might be attributable to the omission of emigration from the model.

For these simulations, we retrieve the historical shocks from the two estimated auxiliary regressions (\( {\epsilon}_t^{\pi n} \) and \( {\epsilon}_t^{\pi q} \)). We then bootstrap the two series of shocks independently 1000 times. We generate 1000 histories or paths of Φn and Φq based on the auxiliary regressions. Then we solve the steady states of the structural model under the 1000 simulated paths of Φn and Φq. For each variable we care about, we obtain the 5% and 95% percentiles to draw the bands (the gray area).

The ratio is defined as food price index over the general RPI index. See online Appendix for details.

Other variables tested but found insignificant were birth control technology (based on illegitimacy and a user survey), female literacy, and domestic appliances (based on electricity connections).

Strulik and Weisdorf (2008) use the ratio of food prices to manufactures, but we judge that a ratio of food prices to all goods and services is more relevant to child costs.

The two effects are not additive, however, because reductions in the wage premium are associated with higher female literacy.

References

Allen RC (2001) The great divergence in European wages and prices from the middle ages to the First World War. Explor Econ Hist 38:411–447

Allen RC (2009) Engels’ pause: technical change, capital accumulation, and inequality in the British industrial revolution. Explor Econ Hist 46(4):418–435

Allen RC (2015) The high wage economy and the industrial revolution: a restatement. Econ Hist Rev 68(1):1–22

Banks JA, Banks O (1954) The Bradlaugh-Besant trial and the English newspapers. Popul Stud 8(1):22–34

Bar M, Leukhina O (2010) The role of mortality in the transmission of knowledge. J Econ Growth 15:291–321

Becker GS (1981) A treatise on the family. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Becker GS, Murphy KM, Tamura R (1990) Human capital, fertility, and economic growth. J Polit Econ 98(5):S12–S37

Bhattacharya J, Chakraborty S (2017) Contraception and the demographic transition. Econ J 127(606):2263–2301

Blanchard O, Kahn C (1980) The solution of linear difference models under rational expectations. Econometrica 48(5):1305–1311

Booth C (1886) Occupations of the people of the United Kingdom 1801–1881. J R Stat Soc 49(2):314–444

Boucekkine R, De La Croix D, Licandro O (2003) Early mortality declines at the Dawn of modern growth. Scand J Econ 105(3):401–418

Bowley AL (1937) Wages and income in the United Kingdom since 1860. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Brezis E, Ferreira R (2016) Endogenous fertility with a sibship size effect. Macroecon Dyn 20(8):2046–2066

Broadberry SN, Bruce MS, Campbell, Klein A, Overton M, van Leeuwen B (2015) British economic growth, 1270–1870. Cambridge University Press

Cervellati M, Sunde U (2005) Human capital formation, life expectancy, and the process of development. Am Econ Rev 95(5):1653–1672

Cervellati M, Sunde U (2015) The economic and demographic transition: mortality, and comparative development. Am Econ J Macroecon 7(3):189–225

Chesnais JC (1992) The demographic transition: stages, patterns and economic implications; a longitudinal study of sixty-seven countries covering the period 1720–1984, Oxford

Choo E, Siow A (2006) Who marries whom and why. J Polit Econ 114(1):175–201

Cinnirella F, Klemp M, Weisdorf J (2017) Malthus in the bedroom: birth spacing as birth control in pre-transition England. Demography 54:413–436

Clark G (2005) The condition of the working class in England, 1209 to 2004. J Polit Econ 113:1307–1340

Clark G (2007) The long march of history: farm wages, population, and economic growth, England 1209–1869. Econ Hist Rev 60(1):97–135

Clark G (2018) What were the British earnings and prices then? (new series). MeasuringWorth http://www.measuringworth.com/ukearncpi/

Clark G, van der Werf Y (1998) Work in progress? The industrious revolution. J Econ Hist 58(3):830–843

Colgrove J (2002) The McKeown thesis: a historical controversy and its enduring influence. Am J Public Health 92(5):725–729

Crafts NFR (1984) A time series study of fertility in England and Wales, 1877–1938. J Eur Econ Hist 13(3):571–590

Crafts N, Mills TC (2009) From Malthus to Solow: how did the Malthusian economy really evolve? J Macroecon 31(1):68–93

Cummins NJ (2009) Why did fertility decline? An analysis of the individual level economic correlates of the nineteenth century fertility transition in England and France. A thesis submitted to the Department of Economic History of the London School of Economics for the degree of doctor of philosophy, London, June 2009 http://etheses.lse.ac.uk/39/1/Cummins_Why_did_fertility_decline.pdf

Curtis SJ (1961) History of education in Great Britain. University Tutorial Press

De la Croix D, Licandro O (2012) The child is father of man: implications for the demographic transition. Econ J 123(567):236–261

De Witte S, Wood J (2008) Selectivity of black death mortality with respect to preexisting health. Proc Natl Acad Sci 105(5):1436–1441

Doepke M (2005) Child mortality and fertility decline: does the Barro–Becker model fit the facts? J Popul Econ 18:337–366

Duranton G, Puga D (2014) The growth of cities. In: P Aghion and S Durlauf (eds.), Handbook of economic growth, edition 1, volume 2, chapter 5, 781–853, Elsevier

Dutta R, Levine DK, Papageorge NW, Wu L (2018) Entertaining Malthus: bread, circuses, and economic growth. Econ Inq 56(1):358–380

Feinstein CH (1998) Pessimism perpetuated: real wages and the standard of living in Britain during and after the industrial revolution. J Econ Hist 58(3):625–658

Foreman-Peck J, Zhou P (2018) Late marriage as a contributor to the industrial revolution. Econ Hist Rev 71(4):1073–1099

Galor O (2005) From stagnation to growth: unified growth theory. In: P Aghion and SN Durlauf (eds) Handbook of economic growth. Elsevier, vol 1A, pp 171–293

Galor O (2011) Unified growth theory. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Galor O (2012) The demographic transition: causes and consequences. Cliometrica 6:1–28

Galor O, Michalopoulos S (2012) Evolution and the growth process: natural selection of entrepreneurial traits. J Econ Theory 147(2):759–780

Galor O, Moav O (2002) Natural selection and the origin of economic growth. Q J Econ 117(4):1133–1191

Galor O, Weil DN (2000) Population, technology, and growth: from Malthusian stagnation to the demographic transition and beyond. Am Econ Rev 90(4):806–828

Gilboy EW (1936) The cost of living and real wages in eighteenth century England. Rev Econ Stat 18(3):134–143

Guinnane TW (2011) The historical fertility transition: a guide for economists. J Econ Lit 49(3):589–614

Hajnal J (1965) European marriage patterns in perspective. In: DV Glass and DEC Eversley (eds) Population in history: essays in historical demography. Edward Arnold

Hatcher J (2011) Unreal wages: long-run living standards and the ‘Golden age’ of the fifteenth century. In: Dodds B, Liddy CD (eds) Commercial activity, markets and entrepreneurs in the middle ages. Boydell Press, Woodbridge, pp 1–24

Healey J (2008) Socially selective mortality during the population crisis of 1727–1730: evidence from Lancashire. Local Popul Stud 81(81):58–74

Horrell S, Humphries J (1995) Women’s labour force participation and the transition to the male breadwinner family 1790–1865. Econ Hist Rev, 2nd Ser 48:89–117

Humphries J (2012) Childhood and child labour in the British industrial revolution. Cambridge

Humphries J, Weisdorf J (2015) The wages of women in England 1260–1850. J Econ Hist 75:405–445

Humphries J, Weisdorf J (2019) Unreal wages? A new empirical foundation for the study of living standards and economic growth in England, 1260–1850. Econ J 129(623):2867–2887

Hunt EH (1986) Industrialization and regional inequality: wages in Britain, 1760–1914. J Econ Hist 46(4):935–966

Keeley MC (1977) The economics of family formation. Econ Inq 15(2):238–250

Klemp M, Weisdorf J (2019) Fecundity, fertility and the formation of human capital. Econ J 129:925–960

Lagerlof N-P (2003) Mortality and early growth in England, France and Sweden. Scand J Econ 105(3):419–439

Lagerlof N-P (2006) The Galor–Weil model revisited: a quantitative exercise. Rev Econ Dyn 9:116–142